Survey research controversy, white anti-racist activists, and supernatural beliefs

do ties still bind?

In 2004, nearly one-quarter of Americans reported they couldn’t discuss personal issues with anyone in their lives. Or so the survey tells us.

After examining the data himself, Fischer found many reasons to be skeptical. Other indicators of social connectedness, like evenings spent with friends, changed little over the same time period. And, an unusually high number of Americans typically considered to be well-connected didn’t report a single confidant, including more than 20 percent of married people. The discrepancy may be a result of fatigue among survey respondents, Fischer argues. Surveys can be especially taxing, and the question about confidants followed an unusually lengthy and “intrusive” set of questions about organization membership. Perhaps respondents “learned” that giving a list of close confidants would lead to even more probing.

Or, the problem could be due to random error. Using a series of simulations, Fischer found the jump in isolation may be due to a technical error wherein up to one-fifth of respondents who likely would have given names were randomly recorded as giving none.

The authors of the original study stand by their results, concluding that “any plausible modeling of the data shows a decided trend downward in confidant network size from 1985 to 2004,” even when an inflated number of zeros are taken into account.

Fischer, who is the founding editor of Contexts, suggests a rise in isolated Americans may be possible, but it’s not likely. The continuing debate surrounding social ties also underscores the complexity of social scientific research—sometimes discoveries aren’t so easily made. W.L.

becoming real

People in race-based social movements typically nurture and develop close ties with members of their same race. But what about those who participate in movements dominated by people of other races?

Jill McCorkel and Jason Rodriguez (Social Problems, March 2009) used multi-year participant observation to study how white people become accepted in civil rights organizations dominated by African Americans.

They found that white people are rarely recruited into such organizations and, when a white person seeks membership, they’re often relegated to “supporter” roles rather than given full membership.

In one group the authors studied, members were vetted and then had to demonstrate a clear commitment to black politics while also recognizing their secondary position in the movement. In another, where white people couldn’t be vetted, they often worked hard to wear their politics on their sleeve, so to speak, by sporting political buttons and t-shirts.

In order to move into the core of the movement, white people had to prove their “realness”—their political commitment to the struggle. But regardless of their efforts to “fit-in,” white participants in black social movements never could become “brothers.” K.H.

god is my copilot…to mars

While belief in the supernatural aspects of the Christian faith is relatively mainstream in the United States, believing in the paranormal is often considered bizarre.

Using a nationally representative survey, F. Carson Mencken, Christopher Bader, and Ye Jung Kim (Sociology of Religion, Spring 2009) compare Christian beliefs about God, Jesus, heaven, and hell to belief in fortune-telling, astrology, communication with the dead, haunting, the power of dreams, spaceships, Bigfoot, and Loch Ness. After accounting for a range of variables, they find Christians often believe in the paranormal.

Interestingly, this relationship isn’t constant for all Christians. Attending church, believing the Bible is literal truth, and being evangelical make people less likely to believe in the paranormal. On the other hand, those who have Christian beliefs but aren’t regular church-goers are more likely to take the arguably small step to believing in the paranormal.

Similarly, mainline Protestants and Catholics are more likely to believe in the paranormal—Catholic theology integrates many spiritual, supernatural elements and mainline Protestants tend to be more open to diversity of religious views. For these folks, it seems, Christianity swings open the door to a galaxy far, far away. S.G.

we’ll take (some) huddled masses

But when Andy Rottman, Christopher Fariss, and Steven Poe (International Migration Review, Spring 2009) analyzed Department of Homeland Security cases, they found political context still matters.

Asylum officers have been more likely to deny claims since 2001, and having been subjected to torture or other cruel treatment is a less important determinant in being granted asylum. Instead, language and a home country’s negative relationship with the United States are significant deciding factors.

Perhaps this is the policy Americans want in a post-9/11 society—but it’s clearly not consistent with what our laws say. S.G.

performance paradox

African American students feel good about school—in fact they often report more positive attitudes about the merits of education than white students. However, we also know blacks don’t perform as well as whites, and they earn fewer degrees. As a result, past studies have suggested blacks’ pro-school attitudes are inconsequential for actual academic achievement. However, Douglas B. Downey, James W. Ainsworth, and Zhenchao Qian (Sociology of Education, January 2009) use survey data from the 2000 National Education Longitudinal Study to call this inference into question.

According to the authors, pro-school sentiments do indeed matter for blacks’ academic success and predict educational attainment among them nearly as well as it does for other minorities and whites. Social factors—blacks are more likely than whites to come from poorer and less-educated families and attend schools that possess fewer resources—may impede their ability to translate positive attitudes into achievement. The authors argue that this helps explain the achievement gap that persists between white and black students.

Despite historical disadvantage and discrimination, the authors say there’s reason for hope—the gap between the social conditions of blacks and whites has been narrowing. J.S.

free riders get no respect

Sometimes it makes more sense to let others clean up the local park if we can still enjoy it by sitting under a tree. Unless you care about what others think of you.

Willer developed a series of computer games in which participants had the option to contribute to the group or sit back and reap the rewards. Turns out high contributors were consistently seen as more honorable and generous by other players.

And having status was useful in later games. High-status players gave more to the group and were more likely to get partners to cooperate with them.

Contributions to the group signal a willingness to sacrifice for the greater good. In turn, our concern for how others perceive us allows for more camaraderie and cooperation, Willer argues.

Status may mean more to a potential volunteer than a free t-shirt. After all, nobody likes a free rider—and everyone likes a pat on the back. W.L.

bite your native tongue

Immigrants to the United States who are fluent in both English and their native languages are thought to hold amarketable advantage over immigrants fluent only in English.

However, a study by Hyoung-jin Shin and Richard Alba (Sociological Forum, June 2009) suggests Asian and Hispanic immigrants don’t see any economic benefit from bilingualism, and in some cases are even penalized for it.

Using 2000 U.S. Census data, the authors examined the income of immigrants who were born in or came to the United States in early childhood. When the incomes of bilingual immigrants were compared to those of English-only immigrants, the authors found bilingualism offered no wage benefits, and for Mexican, Chinese, and Filipino immigrants it even decreased wages. Even variables thought to boost the benefits of bilingualism like education, job experience, and a large nearby immigrant population couldn’t push the incomes of most bilingual Asian and Hispanic immigrants above those fluent only in English.

While assimilation into American society surely has its cultural cost, this study suggests losing fluency in one’s native tongue may actually pay. J.S.

this is your brain on opera

In a now classic sociological study from the 1950s, Howard Becker argued that becoming a marijuana smoker involved not only toking up, but an initiation process where novice users learned from others how to recognize and interpret the effects of “being high” as pleasurable.

More recently (Qualitative Sociology, June 2009), Claudio Benzecry took Becker’s model outside the drug subculture and into high culture, demonstrating how individuals learn to become passionate opera fans.

Spending 18 months conducting participant observation and interviewing opera fans in Buenos Aires, he found that to become a proper fan of opera, individuals had to learn how to interpret, direct, and control their intense feelings about the genre appropriately, thereby cultivating in them a refined taste.

According to Benzecry, novice opera fans learned how to “be moved” by parts of the performance that demand an emotional reaction, such as sadness or even crying, as well as how to react publicly to the opera in appropriate ways (through applauding, booing, and hissing).

Much like Becker’s marijuana users, Benzecry’s opera fans cultivated this seemingly individual taste for the operatic experience through social activities such as conversations at ticket and door lines, imitating more experienced fans, and more formal learning that included classes, lectures, and conferences about opera.

By extending Becker’s model to the realm of high culture, Benzecry demonstrates the importance of attending not only to background factors like social class and education in explaining cultural consumption, but to “foreground” factors such as initiation and learning processes as well. D.W.

one step up, two back, another sideways

Some argue the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgendered rights movement suffered a setback after the Massachusetts Supreme Court legalized same-sex marriage because a number of statutory bans on it followed. Indeed, unpopular judicial decisions often provoke political backlash that weakens their effectiveness.

While many states indeed passed statutory prohibitions on same-sex marriage in the wake of these rulings, and such bans were widely publicized, Keck found that several other states enacted some form of legally recognized partnerships. And, many states subsequently adopted hate crime regulations and anti-discrimination laws.

Keck posits that judicial decisions and litigation lend power to several components important for advancing LGBT rights claims, including altering public opinion, changing activists’ perceptions of what’s actually achievable, and pushing transformations in lawmakers’ agendas.

States, according to the author, tend to follow a halting but similar path toward legal reform: decriminalizing sodomy, establishing protections against hate crimes, prohibiting workplace discrimination, establishing some minimal legal recognition for same-sex partnerships, and then expanding the scope of relationship recognition in steps toward marriage equality. T.O.

a hassan by any other name

What’s in a name? As it turns out, quite a bit. Like the degree of someone’s assimilation to a new country.

Jurgen Gerhards and Silke Hans (American Journal of Sociology, January 2009) used data from the German Socio-economic Panel Study and in-depth interviews to learn why some immigrant parents in Germany give their children traditional names of their home country and others give names from the country they now call home.

They found that immigrant parents from Romanic nations, who are typically either Catholic or Protestant and speak a similar language, gave their children German names at a higher rate than immigrants from the former Yugoslavia, who tend to be Eastern Orthodox. The group least likely to give their children German names were Turkish immigrants, who are predominantly Muslim and whose language has little in common with German.

The authors argue these choices can be explained by what scholars call “bright” and “blurry” boundaries between ethnicities. While some cultures have similarreligions or languages that can’t be easily separated, some have stark differences,making the boundaries between them bright and distinct.

For example, because most traditional German names are those of Christian saints, it’s less of a stretch for those from predominantly Christian nations to give their children German names.

Similarly, other factors that blur inter-ethnic barriers, such as higher education levels or attaining German citizenship, were also associated with a greater likelihood of giving a child a German name.

So, it turns out, we can’t apply Shakespeare to cultural assimilation. J.S.G.W.

black boys more geek than gangsta

While white men on television are often depicted as paragons of heroic virtue, black males are overwhelmingly represented as violent thugs and over-sexualized brutes, sociological studies have found.

But tune in children’s programming and African American males are more likely to resemble inept nerds, or so found Jeffery P. Dennis in a recent study of television series aimed at teen and preteen audiences (Media, Culture & Society, March 2009).

Dennis analyzed 112 episodes of 26 series airing on Nickelodeon, the Disney Channel, and Cartoon Network. He discovered that white teen characters, much like their counterparts on adult-oriented shows, are generally competent, sexually desirable, and often heroic. Black teen characters, however, are overwhelmingly “brains” or nerds, inept sidekicks, or bumbling con-artists and pranksters. Furthermore, black male characters are very rarely the objects of feminine desire, and their romantic efforts almost always end in comic failure.

The troubling irony in all this, Dennis points out, is that while teen and preteen television shows reject the dominant stereotypes of black males, they’re replacing them with similarly unattractive depictions. D.W.

understandng condoms in malawi

AIDS is a devastating force in the African nation of Malawi, ranking as the leading cause of death for people ages 15 to 49. While condom use elsewhere has greatly reduced the spread of the disease, Malawians remain highly skeptical of them.

Iddo Tavory and Ann Swidler (American Sociological Review, April 2009) studied recordings of everyday conversations in Malawi and used them to argue that you can’t simply view the decision to use condoms as a choice between healthy rationality and needless risk. Rather, you must understand Malawians’ mutually re-enforcing cultural beliefs about condoms.

First, they fear Western governments are attempting to control their population by spreading cancer via infected condoms. As such, it isn’t a choice between healthy condom use and the risk of AIDS, but rather a balancing act between the risk of two lethal diseases. Second, Malawians place great emphasis on sharing bodily fluids in the act of sex, making sex with a condom not merely less pleasing, but not sex at all. Finally, using condoms signifies a lack of trust in one’s partner, making their use insulting in a loving relationship, even if the partner is suspected to be HIV positive.

These findings have significant policy implications for AIDS-reduction efforts in Malawi. They suggest the answer doesn’t lie simply in more education, but rather in changing how Malawians think about condoms and their sexuality. J.S.G.W.

baby, you’re crampin’ our style

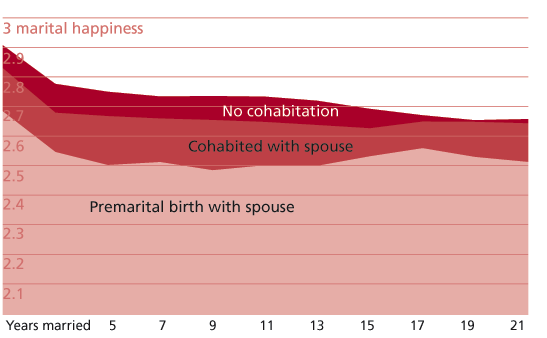

Studies have suggested for years that living together before marriage leads to unhappiness and divorce, but according to Laura Tach and Sarah Halpern-Meekin (Journal of Marriage and Family, May 2009), these findings may have been overstated.

Using data on women from the National Longitudinal Study of Youth, they found few differences in the quality of marriage between those who lived apart from their spouse prior to marriage and those who lived with their spouse and without children before marriage. In fact, most of the link between low marital quality and premarital cohabitation can be explained by the negative experiences of cohabiters who have children prior to marriage.

Notably, marital happiness declines for all three groups over time, and at relatively similar rates.

Because previous researchers have found that marital quality declines after a child is born, the authors argue the same principle may apply to cohabiters, in that their relationship worsens after they have kids. T.O.

singapore demands make little difference in lives

Nearly 90 percent of Singaporeans live in publicly subsidized housing, where residents younger than 35 must form a “family nucleus” before they can buy a unit. The government demands ever-increasing labor productivity and full employment, but also explicitly admonishes women to bear children for the good of the nation.

Youyenn Teo (Signs, Spring 2009) asked 60 Singaporeans why, unlike other East Asians, they tolerated such intrusion by the state into their personal lives, especially when these policies could easily be seen as more harmful to women than men.

She found that Singaporeans recognized the direct intervention of government in their family life and the inequality of government policies that expect women to be the primary caregivers to both children and aging parents. Women often complained of the difficulty ofsatisfying both the economic and childrearing demands of the state.

What Teo didn’t find, however, was any particular anger about the state’s differential treatment. Instead of blaming the state, Singaporeans attributed the policies to the unavoidable result of a vague notion of a Confucian or “Asian” culture emphasizing filial piety.

They saw the role the state played in their personal lives, but they didn’t acknowledge that these policies changed the shape of their family lives or affected the personal decisions they made. Instead, many attributed the government’s actions to well-intentioned attempts to keep up with the needs of the country’s economy.

Teo argues that the state’s open acknowledgment of gendered policies actually leads to greater citizen acceptance. M.K.