I suspect most Soc Images readers will, by now, be familiar with the Bechdel Test — the set of criteria for evaluating whether female characters are included in movies in even minimally non-male-centered ways, made popular by Alison Bechdel of Dykes to Watch Out For. To pass, a movie has to have at least two female characters who have at least one conversation with one another about something other than a man. For a quick overview, see our repost of Anita Sarkeesian discussing the Bechdel Test.

Leah B. let us know that there’s a website, Bechdel Test Movie List, entirely devoted to rating movies based on the criteria (with the stipulation that female characters have to actually be named to count). It consists of a list of movies that have been added and rated by readers; there are currently over 2,000 movies produced between 1900 and 2011 rated on the website. This is, obviously, nowhere near a random sample; as you’d expect, it’s highly weighted toward more recent movies, and of course not everyone agrees on the ratings (you can add a symbol to show you disagree and leave a comment on a movie’s rating page).

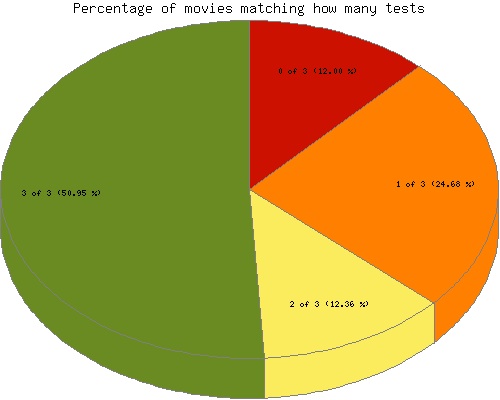

That said, the site includes a stats page that is interesting to look through just for a snapshot of the inclusion of women in these movies. Here’s a breakdown of the entire list; green indicates movies that passed all three tests, yellow passed 2, orange passed 1, and red didn’t pass any of the three:

It’s fun to browse through, for entertainment value and a starting place for thinking about the Bechdel Test and pop culture.