In 2002, a study by Joshua Correll and colleagues, called The Police Officer’s Dilemma, was published. In the study, researchers reported that they presented photos of black and white men holding either a gun or a non-threatening object (like a wallet) in a video game style setting. Participants were asked to make a rapid decision to “shoot” or “don’t shoot” each of the men based on whether the target was armed.

They found that people hesitated longer to shoot an armed white target (and they were more likely to accidentally not shoot). Participants were quicker and more accurate with black armed targets but there were more “false alarms” (shooting them when they were unarmed). These effects were present even though participants did not hold any explicit discriminatory views and wanted to treat all targets fairly.

The effect we see here is a subconscious but measurable preference to give white men the benefit of the doubt in these ambiguous situations. Decision times can vary by a fraction of a second, but that fraction can mean life or death for the person on the other end of the gun.

A terrible reminder of this bias was brought back into the headlines on March 2nd when a black student in Gainesville Florida was shot in the face with a rifle by a police officer. The conditions surrounding the shooting are murky, as the police are extremely hesitant to release details.

It appears that Kofi Adu-Brempong, an international graduate student and teacher’s assistant, was in a stress-induced panic and was worried about his student visa. On the day of the incident, his neighbors heard yelling in his apartment and called the police. It has been suggested that he may have suffered from some mental health problems that related to his panics (although this is not known for sure) and that he had resisted police in the past.

Even so, when the police arrived they broke down his door, citing that they did not know if there was someone else in danger inside the apartment. Adu refused to cooperate and the situation escalated to the point where police tried to subdue him with a tazer and a bean-bag gun. Then a policeman shot him. Adu is now in the hospital in critical condition and has sustained serious damages to his tongue and lower jaw. The police claimed that Adu was wielding a lead pipe and a knife and started violently threatening them with the weapons.

In fact, there was no lead pipe and there was no knife in his hand. When the police approached Adu after he had been shot, the pipe showed itself to be a cane- a cane that Adu constantly used due to a case of childhood polio. And the knife they saw in his hand was actually sitting on the kitchen counter.

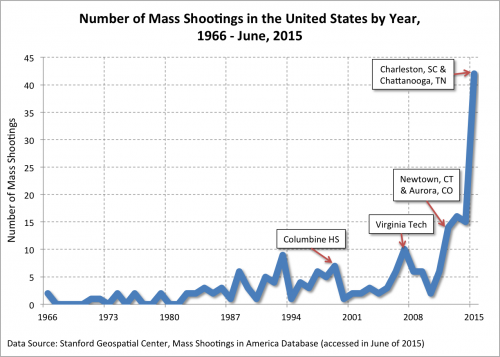

Instances like these are tragic reminders of the mistakes that can be made in split second decisions and how race can play into those decisions.

This post originally appeared in 2010. Re-posted in solidarity with the African American community; regardless of the truth of the Martin/Zimmerman confrontation, it’s hard not to interpret the finding of not-guilty as anything but a continuance of the criminal justice system’s failure to ensure justice for young Black men.

Lauren McGuire is an assistant to a disability activist. She’s just launched her own blog, The Fatal Foxtrot, that is focused on the awkward passage into adulthood.