Pandemics Prey on Fears, Both Legitimate and Illegitimate

In addition to causing thousands of deaths and economic chaos, the global COVID-19 pandemic has also created an intense social environment of fear and anxiety. In response, people in the United States have been hoarding, among other things, toilet paper and guns. Many fears that accompany the pandemic, such as concerns for the health of loved ones and worries about economic instability are clearly legitimate and unavoidable. At the same time, other fears, especially those that spread virally in the digital age, such as those about the imminent imposition of martial law or the secret deployment of new bio-weapons, are illegitimate.

It is the culture and environment of fear surrounding the pandemic we want to address here, rather than the epidemiological dimensions of the crisis. We have been studying the sociological and political dynamics of fear in the U.S. since 2014, the first year we began fielding the Chapman Survey of American Fears (CSAF). We have summarized what we found about the ways that fear can be useful, or as is more often the case socially detrimental, in our book Fear Itself: The Causes and Consequences of Fear in America.

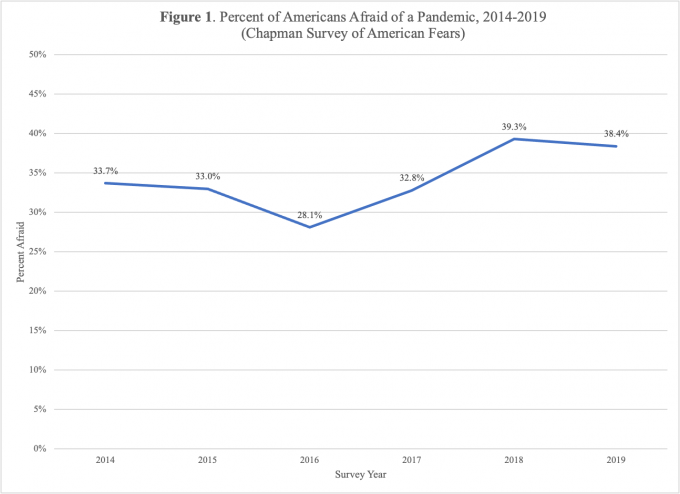

Overall, Americans’ fears about pandemics were relatively stable before 2020 (Figure 1), and were nowhere near the top of the list in terms of what Americans feared the most. No doubt nearly everyone is afraid of a pandemic now that we are living through one. Still, the patterns of fear before the arrival of COVID-19 provide an opportunity to gain some sociological insight into people’s anxieties about pandemics, and also help us understand some of the specific patterns we now find in midst of the pandemic. In particular, we want to focus on two aspects: legitimate fears about economic inequality and illegitimate fears about malevolent conspiracies.

Legitimate Fears

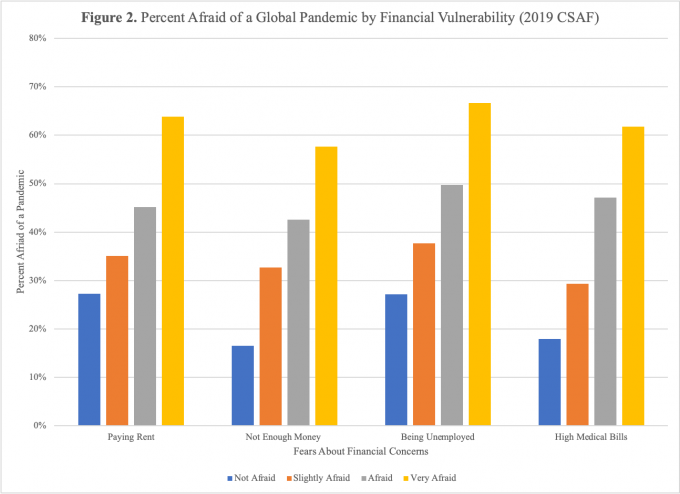

Aside from the fears we all share about health and safety, the most legitimate fears about pandemics are expressed by those who have what we term “social vulnerability,” meaning less access to power and resources. In the U.S., a central issue in regard to health and well-being is who has access to health care services, and whether or not accessing needed care will deplete resources or leave someone deep in debt. Not surprisingly and quite legitimately then, when we examined data from the 2019 wave of the CSAF, the greatest fears about global pandemics were expressed by Americans who were worried about their financial security, particularly with regard to employment, housing, and health care. Even after accounting for sociodemographic characteristics (e.g., race, social class, gender, and age) and political identification, an index of financial concerns was the strongest predictor of fears about a pandemic.

As we are now seeing with the economic effects of the pandemic disproportionately affecting low-income and temporary workers, Americans’ fears about the economic problems a pandemic could cause were well-placed. While the efforts to mitigate COVID-19 may simply mean working from home for some, for many others job loss, housing insecurity, and concerns about accessing and paying for proper medical treatment have quickly becoming terrifying realities. It is the responsibility of all of us, as local communities, states, and a nation to recognize the ways that both the pandemic itself and public health efforts to mitigate it are deepening and entrenching preexisting social inequalities.

Illegitimate Fears

Of course, pandemics do not just activate and realize legitimate concerns, they also generate illegitimate but nonetheless socially consequential fears, particularly moral panics, xenophobia, and conspiracy theories. In terms of the latter, a number of conspiracy theories are already making the rounds on social media and the myriad forums where they germinate in cyberspace, like Reddit and 4Chan. Conspiracy Svengali Alex Jones claims that the virus is a bio-weapon deployed by China against the U.S. and that liberals are trying to prevent Donald Trump from doing his best to contain the virus in order to hurt his reelection changes. Not coincidentally, Jones has also peddled snake oil cures for the virus from his personal line of health products. Echoing the age-old and eternally recurring claims of Satanic Ritual Abuse, conspiracist QAnon advocates claim that the virus and economic slowdown are actually a coverup for the ongoing breakup of a worldwide celebrity pedophile subculture. For its part, China is using disinformation to blame the U.S. for the outbreak, and Russia is using a disinformation campaign to decrease levels of institutional trust in Western democracies.

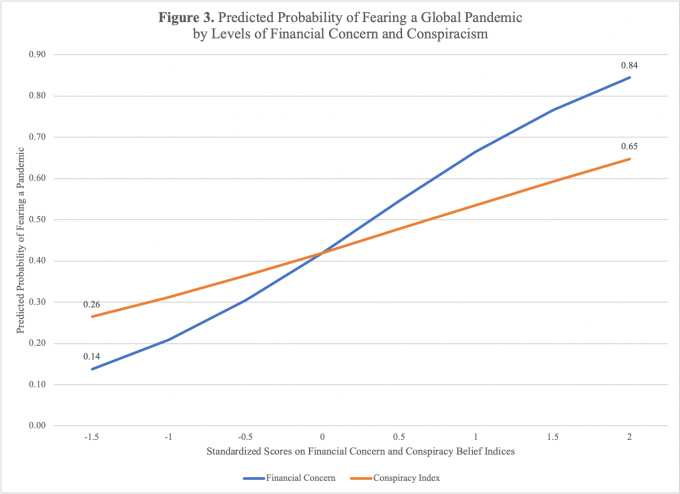

Aside from conspiracies intentionally deployed as part of disinformation campaigns, our extensive research on conspiracy theories and their related subcultures has shown that conspiracies are ideological responses to both fear and uncertainty, two things pandemics bring in spades. Further, there is a preexisting connection between fears about pandemics and the acceptance of conspiracy theories. As part of our surveys, we have been asking respondents to what extent they believe the federal government is attempting to conceal information about a range of standard conspiracy theories, including aliens, the 9/11 attacks, the JFK assassination, the moon landing, the Illuminati/New World Order, and mass shootings. We have also asked whether Americans believe in a government cover-up of the “North Dakota Crash,” a conspiracy we made up to gauge baseline gullibility on these issues. Shockingly, a consistent one-third of respondents to each wave of our surveys have reported believing that the government is hiding what it knows about our faux conspiracy.

In looking at the predictors of fears about a global pandemic in the 2019 CSAF, the second strongest predictor in our model after financial insecurity was an index of belief in conspiracy theories. The more conspiratorial-minded respondents were, the more likely they were to be afraid of pandemics. In this way we see that not only are fear and uncertainty a natural byproduct of pandemics, there is also a preexisting affinity between pandemic fears and ideologies that thrive on these social pathologies, such as conspiracy theories. Hence, the generation and spread of conspiracies about the pandemic was, in many ways, inevitable.

Focusing the Response to Fear in the Right Place

As the epidemiological, economic, and social crises over COVID-19 deepen and extend, it is important to focus our collective efforts to alleviate fear and uncertainty in places where they can be productive, and also to understand where they might be detrimental. Quite obviously, the greatest good can be achieved by focusing resources on the medical needs of testing, access, and adequate medical care. At the same time, the need for economic relief for the millions of people out of work, furloughed, or underemployed must also be a priority. People’s fears about a pandemic in relation to financial insecurity were indeed well-placed.

At the same time, we must also be prepared to combat the inevitable proliferation of conspiratorial claims about the sources, diffusion, and cures related to COVID-19. Not only are conspiracy theories a natural byproduct of a fearful environment, they are also intimately connected to fears about pandemics, specifically. In many ways, the global pandemic combined with the ubiquity of mediated communication in the digital age makes these halcyon days for conspiracism. But these ideological viruses are ones that we actually do create ourselves, and therefore also ones that we already possess the tools to fight, so long as we are willing to do the work. Resisting the siren’s call of the simplistic explanations offered by conspiracy theories is of course easier said than done, but we must all do our parts to mitigate the aspects of the pandemic that we can control. Critically evaluating the information you consume and share about the pandemic and helping dissuade friends, family, and neighbors who unwittingly buy into conspiracy theories is something we can all do to help mitigate the negative consequences of the ongoing pandemic. There is of course no vaccine for conspiracism, but critical thinking, sociological analysis, and open engagement are nonetheless effective therapies.

Joseph O. Baker is as Associate Professor in the Department of Sociology & Anthropology at East Tennessee State University. Ann Gordon is an Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science and Director of The Henley Lab at Chapman University. L. Edward Day is an Associate Professor and Chair of the Department of Sociology at Chapman University. Christopher D. Bader is a Professor of Sociology at Chapman University.