Observing Life and Death in America: Gary Younge

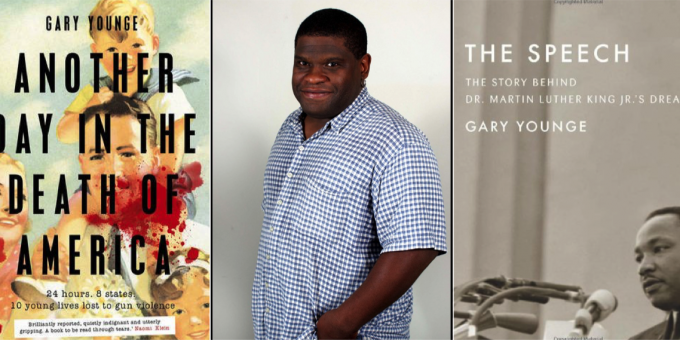

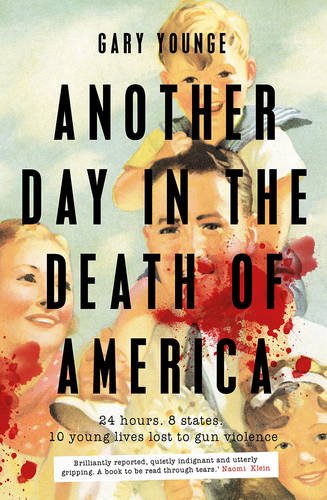

Gary Younge was recently named a Fellow of the Academy of Social Sciences and he won the Harvard Kennedy School’s David Nayan Prize for Political Journalism. And though the Guardian Editor-At-Large and Nation columnist doesn’t consider himself a social scientist, he published some of the most important sociological writing on the contemporary U.S. in 2016 with his new book Another Day in the Death of America: A Chronicle of Ten Short Lives and his ten-part Guardian series on the presidential election as experienced in Muncie, Indiana.

Both projects are deeply revelatory, exploring American race, violence, and politics at the end of the Obama era. Another Day chronicles the gun deaths of ten children in just 24 hours (from 3:57am, November 23, 2013 to 3:30am, November 24, 2013). It is a graphic, heartbreaking portrait of how gun culture shapes (and ends) everyday lives, and it is as readable and engrossing as Matthew Desmond’s Evicted (on precarious housing) or Alice Goffman’s On The Run (on the war on drugs). Even Younge’s Author’s Note at the beginning of the book is a study in critical statistics and social scientific methodology, succinctly framing the work and explaining who is and is not included in his study.

Younge’s deep reporting of Muncie is also steeped in sociology, following in the footsteps of “husband-and-wife sociologists Robert Staughton Lynd and Helen Merrell Lynd” who “scoured America in search of a city ‘as representative as possible of contemporary American life’” and found themselves in Muncie in the 1920s. The Lynds conceded in their work that “[a] typical city, strictly speaking, does not exist,” but that Muncie, which they called “Middletown,” had “many features common to a wide group of communities.” Young worked diligently to write about the people and politics of this mid-western town in a singularly divisive political season.

Contexts board member and fellow Guardian writer Steven Thrasher spoke to Younge from his home in London about Muncie in the time of Trump, choosing the date he did to study child death shootings, and what he’s learned about ethnography and the U.S. along the way.

Steven Thrasher: Why did you pick Muncie for the final stretch of the election?

Gary Younge: Muncie came up as one of the few areas of the right size, where the county had voted for Donald Trump and for Bernie Sanders [in the primaries]. And then I found out it was a swing county, which mattered. It wasn’t the dominant thing, but it was interesting.

I find that covering elections, especially American elections, is quite exhausting… morally exhausting. There is a game that people play. It’s poll-driven, it’s gaffe-driven, and it actually looks at who will win rather than at what will change. It is consumed by what politicians will talk about rather than about what people are talking about. And it eschews a real contest of people and ideas in a system that is gerrymandered. We often deny all of that in order to be an audience in a show. And I’ve never really enjoyed that and think it is silly and wrong.

In 2008, I stayed in Roanoke, Virginia, before I got pulled out to cover the election. It’s a difficult thing to convince editors to let you do, to let you just be somewhere. They want to know: What are you going to find? Well, I don’t know what I am going to find. And they hate that. They want you to find the angry and disaffected people, the women worried about security, or the African Americans enthused by Obama, and you write the story you were sent to write….The entire town could have come down with gonorrhea, but you don’t get to write that story!

In 2004, I drove from [John] Kerry’s hometown to Midland, Texas, home of [George W.] Bush, and along the way I stopped in swing states and talked to the family of a dead soldier in Pennsylvania, third party voters in Iowa, and Muslims in Michigan. I found different things in each place. But this time, I wanted to just be in one place, to see what I found there.

ST: As a journalist transitioning into academia, I am always looking at how people do ethnography. Long before we met, I admired your work and the ways you studied and wrote about the U.S. It seems to me that you do a kind of ethnography. How do you think of it?

GY: I don’t think of it as ethnography. I did play around with the Lynds’ core mission when they set out to study “Middletown.” I didn’t think in their terms, though, to “embed” myself. I am not a trained sociologist. I didn’t think in that word, even though I may have been going to Muncie in that tradition. Being at this stage in my career, I was able to spend enough time in one place to see what was happening, which I couldn’t when I was younger. This time, there was enough time.

There are people who love being close to the candidates during elections. I always thought, the closer you get to them, the less you see. It never appealed to me. One time, I went on Tony Blair’s “Battle Bus.” It was silly most of the time. I was surrounded by other journalists. For 2016, I was able to convince my editors to listen to some questions: Were we looking at what readers want? What do they like? What could make us distinctive? Many responses to the Muncie series were, “This is really distinctive. Thank you for this.” But you don’t know if this is going to be true when you start a project like this.

There are people who love being close to the candidates during elections. I always thought, the closer you get to them, the less you see. It never appealed to me. One time, I went on Tony Blair’s “Battle Bus.” It was silly most of the time. I was surrounded by other journalists. For 2016, I was able to convince my editors to listen to some questions: Were we looking at what readers want? What do they like? What could make us distinctive? Many responses to the Muncie series were, “This is really distinctive. Thank you for this.” But you don’t know if this is going to be true when you start a project like this.

ST: How did you pick the day you wanted to study for Another Day in the Death of America?

GY: That was random. It was the first day I could do, really. I had a book in 2013, The Speech, about the fiftieth anniversary of Martin Luther King’s speech at the March on Washington. I was working on that through the end of September, then October was Black History Month in England. Then I started to work on this book. The date had to be on a weekend. On average, seven kids are killed everyday in the U.S., but it’s always more on the weekend. I needed a date that had at least seven to make it work. Otherwise, it’s a less than average day. I planned to start chasing the story down on a weekend, and that was the first date that came through with seven or more: November 23, 2013.

ST: How did you even come up with the idea to capture an average day of children’s gun deaths?

GY: I wish it was my idea, but it wasn’t. In 2007, the Guardian weekend magazine had suggested this idea for me. It was eight kids a day then, and was going down. There was one kid, Brandon Moore, who was never named in the local press, and he was shot in the back by an off-duty cop. It turns out the cop had shot his wife (but didn’t kill her), had killed a neighbor in a fight, and had killed someone with a DUI. And he was still on the force. This was in Detroit, and Brandon’s name didn’t even make the papers.

There was also Timberlan Addison, a two-year-old who found a gun in the sofa cushions and managed to pull the trigger. And in each story, like this one, there was the initial tragedy, but you could also see the bigger human story. Timberlan’s dad, Timothy, was a drug dealer, and he had Timberlan over the night before, he’d taken him to Denny’s for breakfast, and had fallen asleep. And you get a sense of this quiet young Black man who is engaged with his child when Timberlan dies. When he’s woken up by the gunshot, he rushes Timberlan to the house across the road… and breaks down the door to see if they can help. The daughter in that house was pregnant with Timothy’s child, and he gets the police, not even thinking that he has all of this drug paraphernalia out. So you have the stereotype, if that’s what you want, and then you also have this very loving father, if that’s what you’re able to see.

And that article seemed like a way that one could randomly, not scientifically, could really get underneath how people live.

ST: With the book out and the election over, have you drawn any conclusions about America from the Muncie series and from your work on gun violence?

GY: Not yet. I think it will come. I found the election exhausting. I found the election result—while I thought it was possible, I did not think it was likely. It was like you’re watching a documentary, and then it turned into a slasher movie in the last ten minutes.

I’ve read too many wrong conclusions so far. I think it’s complicated in a range of ways, and for pretty much every assessment in which one would say “The election was about this,” I think, “Yes, but…”. Is this about White supremacy? Yes, but Muncie voted for Obama twice, and then they voted for Trump…. Is it about sexism? Yes, but Black men were twice as likely to vote for Clinton as White women were. Was it about class? Yes, but Black and Latino people were not voting for Trump, while most Trump voters were middle-class or rich. There are serious caveats for every explanation. It is important to act now, but we are going to have to work out what this means and we have to spend some time thinking about it.

ST: You, your wife, and your son and daughter moved back to England recently after many years in the U.S. After reporting so much on police violence and shooting violence that harmed young Black men, did having a Black son factor into your move?

GY: No. There’s a certain fear you have in having Black children anyway, and it becomes specific in having a boy versus having a girl. And that’s true in England, too. But the nature isn’t the same, because the country isn’t the same. Our decision was guided entirely by banal personal reasons. And it would be odd to breathe a huge sigh of relief in Brexit Britain compared to Trump’s America. A big thing to say about Trump that is very important is that this isn’t only a local thing. It’s a global thing. Most countries have their Trumps.

In fact, there is an overlap between the two projects [we’re discussing], which is a desire to address some of the shortcomings of [journalism]. A lot of journalists cover gun deaths in a way which is terrible. “It’s not surprising that someone would get shot over there” is a lot of the perceived wisdom behind the coverage. And I think a lot of the perceived wisdom in the election was attempting to do the same thing.ST: Sure, “It’s not surprising that people voted for Trump if we believe our pre-existing ideas of Trump voters as poor white people”—even if it isn’t true.

GY: Right. I wanted to cover gun death that bore down into, actually, What is really going on here? Which was really edifying for me. Things like saying a shooting was “gang-related”—What do we mean when we say something is “gang-related?” The point of that is meaningful if the shooter and the victim are both members in a gang, and the dispute has something to do with their gang membership. But if the two people are in a gang and they are also intimate partners… they may shoot each other in an act of domestic violence. If two people shoot each other in a library, you don’t say the shooting is library-related. It doesn’t make sense!

Could you look at a shooting of a kid who has nothing to do with a gang, who is shot by a gang member, and say that death is gang-related? You could, but it doesn’t help you understand what actually went on. I understand that term “gang-related” now to be a way of dismissing gun deaths. Similarly, when gangs control a neighborhood, being a member is not a matter of paying dues. There is no membership card. Being a member is no different than being a member of the communist party in Russia in the 1950s or a member of the Baath party in Iraq. Sometimes wearing a gang’s color doesn’t mean anything more than a way of getting through your day.