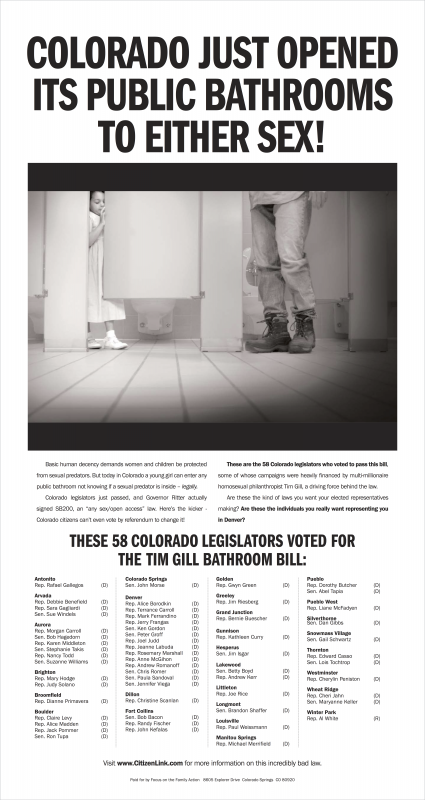

The Massachusetts Family Institute campaign against a "bathroom bill."

Bathroom Battlegrounds and Penis Panics

In January 2008, the city commission in Gainesville, Florida passed an ordinance prohibiting discrimination on the basis of “gender identity and gender expression” in employment and public accommodations (such as public restrooms and locker rooms). Advocates argued that the legislation was a key step toward addressing discrimination against transgender and gender variant people. However, 14 months later voters were considering a ballot initiative to overturn the law.

Even though there had been no reported problems, those that were pushing for the repeal of the new ordinance suggested that such protections had unanticipated, dangerous consequences for women and children. Citizens for Good Public Policy ran a TV ad (below) that featured a young, white girl on a playground. She jumps off a merry-go-round, and, alone, enters a doorway clearly marked “Women’s Restroom.” A moment later, a White man with a scraggly beard, dark sunglasses, and baseball cap slung low on his forehead approaches the door, looks around furtively, and enters. As the door swings shut, the ad cuts to black and the message appears: “Your City Commission made this legal. Is this what you want for Gainesville?”

The question at the heart of the ballot initiative—the place of transgender people in society—has never been a more visible issue than it is today. Advocates for transgender rights have effectively demonstrated that transgender and gender variant people face large-scale discrimination in areas such as employment, housing, and education. Yet, while city and state policies to address such discrimination are rapidly expanding, each new transgender-supportive law or policy typically results in an outbreak of protest.

As sociologists of gender, we were interested in accounting for the opposition to transgender rights in the face of greater societal acceptance of transgender people, as it presents a puzzling aspect of gender: why are transgender people accepted in some spaces and not others? We did a content analysis of media articles about transgender-inclusive legislation from 2006-2010, and discovered that the Gainesville ad was not an anomaly. Opponents of transgender recognition often brought up the specter of sexual predators in sex-segregated spaces as an argument against the passage of transgender rights legislation. Interestingly, such fears centered exclusively on women’s spaces, particularly restrooms.What do sexual predators have to do with transgender rights? Moreover, why is the concern only about women’s spaces? In our research, we find that opponents are making an argument against any bodies perceived as male having a legal right to enter a woman-only space because they imagine such bodies to present a sexual danger to women and children. Under this logic, they often conflate “sexual predators” (imagined to be deviant men) and transgender women (imagined to be always male). This exclusive focus on “males” suggests that it is genitals—not gender identity and expression—that are driving what we term “gender panics”—moments where people react to a challenge to the gender binary by frantically asserting its naturalness. Because most people are assumed by others to be heterosexual, sex-segregated bathrooms are imagined by many people to be “sexuality-free” zones. Opponents’ focus on bathrooms centers on fears of sexual impropriety that could be introduced by allowing the “wrong bodies”—or, to be more precise, penises—into spaces deemed as “for women only.” Gender panics, thus, could easily be relabeled “penis panics.” The shift from gender panics to penis panics as a point of analysis accounts for critics’ sole focus on the women’s restroom—a location that, opponents argue, should be “penis-free.”

While such arguments are not always politically effective—Gainesville, for instance, did not repeal its ordinance—they reinforce gender inequality in a number of ways. Opponents disseminate ideas that women are weak and in need of protection—what one of us (Laurel Westbrook) frames as creating a “vulnerable subjecthood”—and that men are inherent rapists. At the same time, they generate fear and misunderstanding around transgender people along with the suggestion that transgender people are less deserving of protection than cisgender women and children (cisgender people are those whose gender identity conforms to their biological sex). As such, the battle over transgender people’s access to sex-segregated spaces is both about transgender rights and about either reproducing or challenging damaging beliefs about what it is to be a man and what it is to be a woman.

Transgender Rights Legislation to “Bathroom Bills”

The public response to transgender-supportive policies has varied across different social contexts. Within gender-integrated settings, such as college campuses and workplaces, the trend toward transgender-inclusive health care coverage and non-discrimination policies in terms of hiring and promotion has become widely accepted as an important dimension of diversity. Yet, transgender inclusion in sex-segregated settings has proven to be more controversial. In particular, the part of inclusive policies that allows transgender people to use a bathroom that aligns with their gender identity and expression—rather than with their chromosomes or genital configurations—has generated a great deal of opposition.

Supportive politicians and advocates frame transgender rights policies as a way to alleviate discrimination against transgender and gender variant people. Opponents, in contrast, reframe the debate as being about bathroom access. This concerted effort to focus on bathrooms was evident in the media accounts we analyzed. Critics did not discuss “transgender rights legislation,” but rather “bathroom bills.” Reporters picked up on this aspect of the debate, creating pithy, attention-grabbing headlines such as “Critics: Flush Bathroom Bill” (Boston Herald) and “Bathroom Bill Goes Down the Drain” (New Hampshire Business Review).

Opponents repeatedly expressed their belief that public restrooms have to be segregated on the basis of gender and that people’s genitals, not their gender identities, should determine bathroom access. Kris Mineau of the conservative Massachusetts Family Institute, quoted in The Republican, worried about the potential outcome of the proposed state transgender rights bill. “This is a far-reaching piece of legislation that will disrupt the privacy of bathrooms, showers, and exercise facilities including those in public schools… . This bill opens the barn door to everybody. There is no way to know who of the opposite biological sex is using the facility for the right purpose.” Evelyn Reilly, a spokesperson for the same institute, told The Berkshire Eagle, “Men and women bathrooms [sic] have been separated for ages for a reason… . Women need to feel private and safe when they’re using those facilities.”In actuality, the segregation of public bathrooms on the basis of gender is a relatively recent phenomenon in the United States. Prior to the Victorian era, men and women used the same privies and outhouses. With the invention of indoor plumbing came water closets and later bathrooms, which were not segregated until Victorian ideals of feminine modesty—and the mixing of men and women in factory work—established a new precedent. By the 1920s, laws requiring segregated public facilities were de rigueur across the country. As sociologist Erving Goffman has pointed out, men and women share bathrooms in their homes. In public restrooms, by contrast, the sense that men and women are opposite is exacerbated by the placement of open urinals in men’s rooms and the private stalls found in women’s rooms. Such separation, then, is not biologically necessary but rather socially mandated. Highlighting this point, bathroom segregation is not universal, as some European countries, such as France, often have gender-integrated public restrooms.

Transgender-supportive policies present a sharp challenge to this bathroom segregation logic. Opponents struggle with the sense that their belief in a static gender binary determined by chromosomes and genitals is being undermined by institutional and governmental support for transgender people. The outcome of the resulting gender panics is often a call to socially reinforce what opponents position as a natural division of men and women. In a “Letter to the Editor” in The Bangor Daily News, a concerned author contests transgender bathroom access, arguing, “What makes an individual able to claim gender? As I always understood it growing up—and I know I am not alone in this—your anatomy dictates your sex.” A follow-up response on The Bangor Daily News “ClickBack” page read, “The policy should be boys use the men’s room and girls use the lady’s room. Identification does not change physical plumbing.”

These ideological collisions between those advocating transgender rights and those who insist on sex at birth determining gender, and the ensuing panics, put into high relief the often-invisible social criteria for “who counts” as a woman and a man in our society. Yet, in our study, such gender panics focused exclusively on the threat that transgender-supportive bills present to cisgender women and children. Highlighting this point, opponents to trans-inclusive policies proposed in Massachusetts and New Hampshire in 2009 and 2010 repeatedly discussed that these policies would, as The Associated Press reported, “put women and children at risk.” It was in these fears of “risk” that the image of the sexual predator emerged.

Enter The Sexual Predator

The conception of the “sexual predator” is deeply gendered. People often assume that they can establish whether someone is a potential sexual threat by simply determining if they are male (possible threat) or female (not a likely threat). Critics charge that transgender rights laws will make such determination difficult and, will, like “sheep’s clothing” on a wolf, give predators open access to those seen as vulnerable. Evelyn Reilly, a spokesperson for the Massachusetts Family Institute, argued that a proposed state-level law protecting gender identity and gender expression would allow “a sexual predator using the guise of gender confusion to enter the restrooms.” In Colorado, Bruce Hausknecht, a policy analyst for the evangelical organization Focus on the Family Action, fought against a proposed transgender rights bill in 2009, stating: “The fear… is that a sexual predator would attempt to enter the women’s facilities, and the public accommodation owner would feel they had no ability to challenge that.” In Nevada in 2009, conservative activist Tony Dane told The Las Vegas Review-Journal that transgender-rights policies would allow men to legally enter women’s restrooms “in drag,” which would “make it easier for them to attack women and evade capture.”

From Gender Panics to Penis Panics

Transgender people, along with gay men and lesbian women, have a long history of being conflated with pedophiles and other sexual predators. Within the articles we analyzed, opponents worried about what transgender women, who they assume have penises, might do if they were allowed access to women-only spaces. Demonstrating such concern, reporters frequently highlighted critics’ fears about “male anatomies” or “male genitalia” in women’s spaces. Transgender women in these narratives are always anchored to their imagined “male anatomies,” and thus become categorized as potential sexual threats to those vested with vulnerable subjecthood, namely cisgender women and children.

In contrast, transgender men—assumed by critics to be “really women” because they do not possess a “natural” penis—are relatively invisible in these debates. Transgender men are mentioned directly by opponents only once in all of the articles we analyzed. After conservative opponent Tony Dane expressed his concern that the proposed Nevada policy would make women “uncomfortable” in the bathroom because they might have to see a transgender woman, a reporter for The Las Vegas Review-Journal asked about his position on transgender men. He stated, “they should use the women’s bathroom, regardless of whom it makes uncomfortable, because that’s where they’re supposed to go.” Transgender men are never referenced as potential sexual threat to women, men, or children. Instead, they are put into a category that sociologist Mimi Schippers labels “pariah femininities.” They are not dangerous to cisgender women and children, but they also do not warrant protection and rights because they fall outside of gender and sexual normativity.

As our research reveals, policies that would allow transgender people to access sex-segregated spaces and do not have specific requirements for genital surgeries generate a great deal of panic. These panics matter, as they frequently result in a reshaping of the language of such policies to require extensive bodily changes before transgender people have access to particular rights and locations. Such changes place severe limitations on transgender people who may not want or cannot afford genital surgeries. Further, while explicit bodily criteria for access to sex-segregated spaces can quell gender panics, these criteria force transgender people into restrictive and normative forms of gendered embodiment that perpetuate the belief that genitals and gender must be linked.Transgender Rights and the Struggle for Gender Equality

In 2011, the National Center for Transgender Equality and the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force published “Injustice at Every Turn,” a report that highlights the findings of the largest ever survey of the experiences of transgender and gender variant people. The report documents wide-ranging experiences of discrimination. For instance, respondents had double the rate of unemployment compared to the general population and 90% reported experiencing workplace discrimination, including being unable to access a bathroom at work that matched their gender identity.

Anti-discrimination legislation that offers protections for a person’s gender identity and gender expression is an important strategy for addressing inequality in hiring and promotion. Additionally, these policies allow transgender people to use public accommodations, such as bathrooms, in line with their gender identity. In other words, a transgender man with a beard would not be legally required to use the women’s restroom simply because he had been assigned female at birth. While the adoption of transgender-supportive policies has grown rapidly at the state, city, and corporate level in the last ten years, in 2015 there are limited federal protections—a situation that would be addressed by the passage of the Employment Non-Discrimination Act (also known as ENDA). The regional variation in protection for gender identity and gender expression—and the widespread violence and discrimination aimed at transgender people—makes this a key political issue for gender equality.

Unmasking the Real Debate

Gender panics gain legitimacy in the realm of debate because many people believe that women and young children are inherently vulnerable and in need of protection from men. In dominant U.S. culture, men—or more specifically, people assumed to have penises—are both conceived of as the potential protectors of vulnerable people they have relational ties to, such as wives, sisters, daughters, and mothers, and a potential source of sexual threat to others. This idea emerges from a belief that men constantly seek out sexual interactions and will resort to violence to achieve these desires. As transgender women are placed into the category of persons with penises—making them, for many opponents, “really men”—they become an imagined source of threat to cisgender women and children. And, as there are no protective men present in women’s restrooms, opponents to transgender rights imagine women (and often children, who are likely to accompany women to the restroom) as uniquely imperiled by these non-discrimination policies.

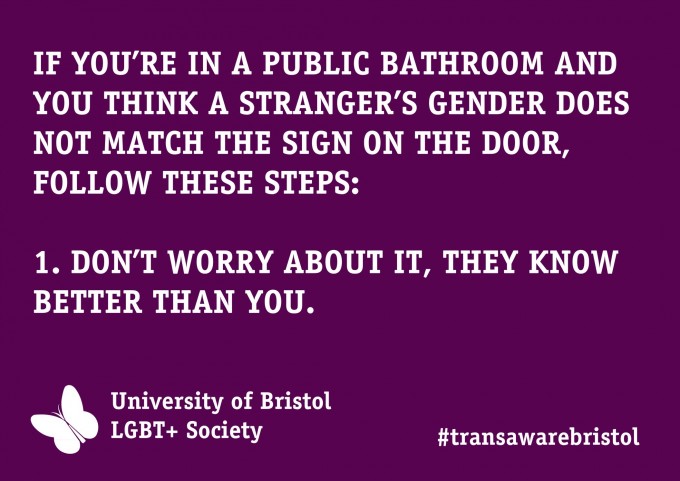

Proponents of transgender-inclusive laws and policies can make strong arguments about the need for protections. The increasingly large body of empirical data on transgender people in the United States emphasizes that transgender people are much more likely to face violence in the restroom rather than to perpetrate such violence. In fact, in none of the media accounts we analyzed have opponents been able to cite an actual case of bathroom sexual assault after the passage of transgender-supportive policies. But deep-rooted cultural fears about the vulnerability of women and children are hard to counter.

It is not to be suggested that sexual assault is not a serious and troubling real issue; rather, such assaults rarely occur in public restrooms and no cities or states that have passed transgender rights legislation have witnessed increases in sexual assaults in public restrooms after the laws have gone into effect. Raising the specter of the sexual predator in debates around transgender rights should be unmasked for the multiple ways it can perpetuate gender inequality. Under the guise of “protecting” women, critics reproduce ideas about their weakness, depict males as assailants, and work to deny rights to transgender people. Moreover, they suggest that there should be a hierarchy of rights in which cisgender women and children are more deserving of protections than transgender people.Beliefs about gender difference form the scaffolding of structural gender inequality, as those that are “opposite” cannot be equal. Thus, bathroom sex-segregation must be reconsidered if we want to push gender equality forward. Many college campuses are moving toward gender-integrated bathrooms and widespread availability of gender-neutral bathrooms. And, in California, bill AB1266, passed in 2013, authorizes high school students to use bathrooms that fit their gender identity and gender expression. These examples demonstrate that the social order of the bathroom can change. While such changes may spark gender panics, these examples suggest that the battles fought over bathroom access can be won in favor of gender equality.

Recommended Readings

Sheila Cavanagh. 2010. Queering Bathrooms: Gender, Sexuality, and the Hygienic Imagination. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press. An instructive and exhaustive look at the cultural construction of bathrooms, including how they maintain binary understandings of gender and disadvantage queer and transgender people.

Erving Goffman. 1977. “The Arrangement Between the Sexes,” Theory and Society 4(3): 301-331. This classic article theorizes the social construction of gender by exploring several venues, including bathrooms, which are designed to support the deeply held view that males are opposite and superior to females.

Jaime M. Grant, Lisa A. Mottet, Justin Tanis, Jack Harrison, Jody L. Herman, and Mara Keisling. 2011. Injustice at Every Turn: A Report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey. Washington, D.C.: National Center for Transgender Equality and the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force. Summarizes the findings of the largest ever survey of transgender and gender variant people, including experiences of unemployment, discrimination, and violence.

Harvey Molotoch and Laura Noren (eds). 2010. Toilet: Public Restrooms and the Politics of Sharing. New York: New York University Press. An interdisciplinary set of essays examining the history and implication of public restrooms.