New Ways of Bowling Together

I once played kickball for Tibet. It was fun.

Mostly, I remember it was a beautiful day, and I won a gift card for a local coffee shop—which more than offset the $10 “donation” I made to Students for a Free Tibet. But it was kind of sad because so few people showed up that everybody won something in the raffle. Even if those raffle prizes had been donated, and even if the organization made money, I still felt like I cheated the system. I don’t think many Tibetans would be inspired by my self-sacrifice.

The charity bike ride to fight AIDS was different. At least it felt different. Four days into the 400-mile bicycle ride, I noticed that one of the riders had affixed two large bandages to the backs of her calves. Written on them in black marker was the phrase, “THESE LEGS FIGHT AIDS.” Suddenly, everything made sense. Those words summed it up: the desire that those 400 miles of sore butts, burning legs, and sweat (if not blood and tears) would mean something. They meant determination. They meant struggle. They meant caring.

To sociologists, this phenomenon presents a variety of puzzles. Do people participate because of an altruistic concern for others or merely a selfish desire to have fun? Is this kind of civic engagement old or new? What does it say about our society if civic recreation is replacing Lions Clubs and PTAs as an ideal way of getting involved in public life? There are no simple answers to these questions, but new evidence shows that the “fitness boom” breathed new life into an old civic form—not because it is an efficient way to raise money, but because it resonates with the cultural value of hard, bodily labor and with narratives of suffering for a noble cause.

the changing civic repertoire

Research on civic engagement is never just about civic engagement; it is also about the promise of democracy and the everyday meanings of citizenship. So the stakes were high when Robert Putnam, in his influential book Bowling Alone, showed that a variety of forms of civic engagement—from voting to membership in voluntary associations—were on the decline in the U.S. To read his book is to feel a mountain of data weighing upon you, creating an unpleasant fear that individualism is usurping our capacity to make democracy work. Many scholars confirmed Putnam’s thesis with evidence of their own, but his critics pointed out that some forms of civic engagement, such as volunteering and political advocacy, were actually on the rise.

As scholars weighed evidence on both sides, it became clear that American civic life was changing, if not necessarily declining. Putnam’s image of the lone bowler symbolizing an anemic democracy wasn’t quite right, but the political significance of bowling is less absurd than his critics realized. There may be fewer people in bowling leagues today, but bowlers might be raising more money for charity than ever before. Recreational opportunities feature prominently in the contemporary civic repertoire.

Civic recreation illustrates both what is old and what is new about contemporary civic engagement. On one hand, there is nothing new about using a leisure activity to raise money for charity. Benefit dinners, charity auctions, and dance marathons have existed for decades, and they all promise a good time in exchange for supporting a good cause. On the other hand, fitness fundraisers—running, walking, or performing some other athletic feat to raise money for some cause—are relatively new. Fitness fundraisers represent a recent innovation on an old civic form, and the story of civic recreation’s transformation is also the story of some significant economic, cultural, and political changes in American society.

the transformation of civic recreation

Fitness fundraisers emerged in the late 1960s as walkathons to combat hunger. The first walkathon in the U.S., the Walk for Development, was held in 1968 by the American Freedom from Hunger Foundation. Hundreds of similar walks followed suit: Project Bread organized its first Walk for Hunger in 1969, the same year that the Church World Service began the CROP Hunger Walks. The March of Dimes organized the first Walk America in 1970. It is striking that this tactical innovation occurred during a period of social upheaval: sociologist Michael Schudson argues that it was around this time that a new ideal of “rights-bearing” citizenship emerged. The citizen who came out of the 1960s was keenly aware of how “the personal is political,” and as a result, developed a number of new techniques of political activism—at about the same time that other techniques began the decline documented by Putnam.

In the 1970s and ’80s, fitness fundraisers spread across the nonprofit sector. People weren’t just walking, and it wasn’t just to fight hunger. Nonprofit professionals coupled myriad causes with myriad fitness activities. For example, in 1978 the American Heart Association launched a fundraiser based in schools and called it Jump Rope for Heart; in it, elementary students ask for donations for heart and stroke research. The event promises to promote physical fitness and combat obesity among students, who receive “thank-you incentives” (that is, toys) in return for meeting pledge goals. Biking and running events became common in the 1980s, as the number of health charities organizing them expanded. In 1980, the National Multiple Sclerosis Society organized its first bike ride to raise money for MS research. The two most popular fitness fundraisers today also started during this time: the Susan G. Komen Foundation’s Race for the Cure (1983) and the American Cancer Society’s Relay for Life (1985).

In the 1970s and ’80s, fitness fundraisers spread across the nonprofit sector. People weren’t just walking, and it wasn’t just to fight hunger. Nonprofit professionals coupled myriad causes with myriad fitness activities. For example, in 1978 the American Heart Association launched a fundraiser based in schools and called it Jump Rope for Heart; in it, elementary students ask for donations for heart and stroke research. The event promises to promote physical fitness and combat obesity among students, who receive “thank-you incentives” (that is, toys) in return for meeting pledge goals. Biking and running events became common in the 1980s, as the number of health charities organizing them expanded. In 1980, the National Multiple Sclerosis Society organized its first bike ride to raise money for MS research. The two most popular fitness fundraisers today also started during this time: the Susan G. Komen Foundation’s Race for the Cure (1983) and the American Cancer Society’s Relay for Life (1985).

The timing of this tactic’s diffusion is significant for economic, cultural, and political reasons. Civic recreation provides nonprofit organizations with a financial buffer against fluctuations in government funding, which is often their single largest source of revenue. The Reagan administration brought about a sharp contraction in government funding for nonprofit social services, even as the sheer number of nonprofit organizations in the U.S. grew to record highs. Thus, civic recreation helps nonprofit organizations maintain steady revenue streams in uncertain financial times, and successful fundraisers provide them with a competitive advantage in securing donors in an increasingly crowded nonprofit sector.

Culturally, the emergence of fitness fundraisers coincided with the “fitness boom” in the U.S., a period marked by the growth of the health and fitness industry and the increasing popularity of hobbies like jogging and cycling. Not simply a healthy lifestyle choice, individual fitness became an important cultural value and a marker of middle-class status, thanks to its promotion by apparel companies, the fitness publishing industry, and mass media. Having a physically fit body, and the accessories to match, became a symbol of one’s social and moral fitness as well. Owning the newest pair of Nike Air Jordans might not improve your game, but it could work wonders for your style and social status.

Scholar and critic Samantha King argues in her book Pink Ribbons, Inc. that these economic and cultural changes are also political. The rise of fitness fundraisers and cause-related marketing is part of a broader conservative shift in American politics and the dismantling of the welfare state. In the 1980s, President Reagan and other conservatives abdicated social responsibility while advocating personal responsibility for addressing social problems. Individuals who lacked social fitness had only themselves to blame, and nonprofit organizations turned to for-profit activities to make up for the decline in public funding.

Scholar and critic Samantha King argues in her book Pink Ribbons, Inc. that these economic and cultural changes are also political. The rise of fitness fundraisers and cause-related marketing is part of a broader conservative shift in American politics and the dismantling of the welfare state. In the 1980s, President Reagan and other conservatives abdicated social responsibility while advocating personal responsibility for addressing social problems. Individuals who lacked social fitness had only themselves to blame, and nonprofit organizations turned to for-profit activities to make up for the decline in public funding.

As for what has happened to civic recreation since the ‘80s, quite frankly, we don’t know for sure. Detailed, representative data on nonprofit fundraising is hard to come by. Most information comes from the Internal Revenue Service, since every 501(c)(3) organization must report its revenues and expenses each year on IRS Form 990 in order to maintain tax-exempt status. The IRS requires organizations to report “special events” revenue, but the groups don’t have to provide many details about the nature of those events. Moreover, revenue from fitness fundraisers are sometimes lumped in with “direct public support,” making it indistinguishable from direct financial donations.

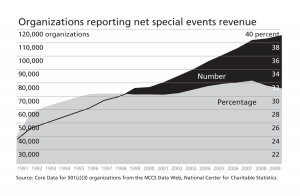

Imperfect though the data may be, the number of organizations reporting any special events revenue whatsoever is an indicator of the prevalence of civic recreation. As the graphic on p. 30 shows, the number of organizations reporting special events revenue has risen, in both relative and absolute terms. Between 1991 and 2007, the percentage of organizations reporting net revenue from special events increased from 24.1 to 32.4 percent. In absolute terms, the number reporting special events revenue tripled during this time. So, we know the sheer number of civic recreation opportunities to which Americans have been exposed has increased significantly.

Ironically, this growth may have occurred in spite of, rather than because of, any financial benefits. While these events hold the promise of stabilizing revenues, they frequently lose money for the sponsoring organization. Charity Navigator, an “independent charity evaluator,” found in a 2007 study that organizations spent $1.33 for every $1.00 raised by a special event, compared with $0.13 spent for each $1.00 raised in total. Here again, though, we do not know the true financial impact of civic recreation, because many special events are not reported as such.

Ironically, this growth may have occurred in spite of, rather than because of, any financial benefits. While these events hold the promise of stabilizing revenues, they frequently lose money for the sponsoring organization. Charity Navigator, an “independent charity evaluator,” found in a 2007 study that organizations spent $1.33 for every $1.00 raised by a special event, compared with $0.13 spent for each $1.00 raised in total. Here again, though, we do not know the true financial impact of civic recreation, because many special events are not reported as such.

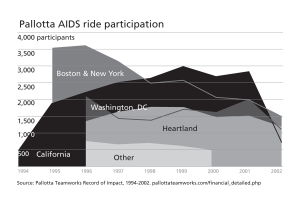

Further, whether or not an event is financially successful may be unrelated to the overall presence of civic recreation in the American civic repertoire. Even if individual events fail, the sheer amount of civic recreation taking place will still rise. Take, for example, Pallotta Teamworks, a for-profit event planner with a checkered past. Best known as the sponsor of the California AIDS Ride, this organization was a pioneer of the multi-day, multi-thousand-dollar-pledge fundraiser (the template for the AIDS bike ride described here). The organization closed its doors in 2002 amid declining participation and controversy about the inefficiency of its events. As the graphic (above left) shows, Pallotta’s events seem anything but successful.

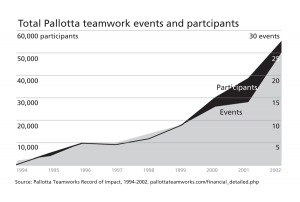

However, even as individual events were failing, the sheer number of participants was booming, tracking a similar increase in the overall number of events. If, as the graphic on the right suggests, the prominence of civic recreation in the American civic repertoire does not depend on its economic success, the source of its apparent popularity must be located elsewhere.

suffering bodies and fit citizens

All actions are laden with meaning. For instance, we buy Girl Scout cookies because they’re delicious, but each purchase carries an additional value: it teaches a young girl that success comes from hard work. There is no such thing as a free lunch. Similarly, our hearts—and our money—go out to the Salvation Army bell-ringers at Christmas time as they devote their time and labor to the singular task of ringing bells for pocket change. They suffer bodily in the freezing cold, like the poor and homeless they want to help.

Civic recreation, too, is popular in part because it resonates with a deeply held cultural value of hard work through bodily labor. Rather than simply writing a check, it feels good to actually do something for the cause you believe in. Civic recreation tries to unite the value of individual fitness with judgments of social and moral fitness in a healing way. In the face of physical and social ills—for we cannot deny their existence—conscientious citizens try to heal the individual and the social body in whatever ways they can. As an ordinary citizen, if I cannot enact complex, structural solutions, then what can I do?

I can ride a bicycle. When I signed up for ACT II (AIDS Network Cycles Together, II), I learned that the $1500 in donations that I would have to raise to participate in this bike ride would go toward HIV prevention services and a variety of legal, medical, and social services for people with AIDS (PWAs). Some people might prefer to simply write a check and skip the 400 miles of bike riding, but not I. As a practical matter, I couldn’t write such a large check myself, but together with friends and family we could. Plus, let’s be honest: I love cycling and this ride would be a great way to see the rolling hills of southwestern Wisconsin.

But that is not why I was standing hand-in-hand with strangers, people I had just met, listening to the sounds of a lone bagpiper, watching a solemn procession of people and objects that symbolized AIDS as they moved down an aisle of weeping humanity. By the time of those Closing Ceremonies—after six days of riding, eating, and sleeping together—I knew there was a deeper reason I had chosen to ride my bike. It was expressed in the narrative of suffering, fitness, and determination that we constructed collectively.

The event organizers worked meticulously to immerse us participants in HIV/AIDS symbolism, from the mundane to the prophetic. Little red ribbons were everywhere. There was a rider-less bicycle, “Rider Zero,” that accompanied our caravan to represent all of the PWAs who had died or were too sick to ride. Organizers used these symbols and other practices to tell a story of bodily suffering and determination to overcome it—the suffering that you feel trying to ride a bicycle up a hill is indicative of the suffering that PWAs experience every day. It is only through persistence and determination that you get to the top, just as only persistence and determination will win the fight against HIV/AIDS, whether in the individual or the social body.

Participants and other volunteers reinforced the organizers’ narrative. One rider, Brett, a veteran of six AIDS rides, told me a story of physically and emotionally living this metaphor: On a previous ride, after riding 300 miles in three days, he came upon a cemetery with red ribbons tied to the fence, and he broke down crying. The combination of physical exhaustion and the symbolic reminders of his friends who had died simply overwhelmed him. Even HIV-positive participants reinforced the metaphor connecting physical exertion with the fight against AIDS. On the fifth day after dinner, Josh stood up and announced to everyone present: “As an 11-year survivor of being HIV positive, I am alive today because of you. So thank you, thank you all for riding.” In response, everyone cheered and applauded like crazy. Who wouldn’t feel their efforts validated by such testimony?

In addition to these symbols and metaphors, we strove to enact the kind of caring, compassionate community needed to combat HIV/AIDS. Ordinary bike rides are frequently quiet and solitary, but organizers and volunteers worked assiduously to create a norm of boisterous cheering and mutual encouragement. Some volunteers acted as cheerleaders each day, parking their cars at the top of steep hills and yelling words of encouragement: “Looking good rider!” “You can do it!” Cyclists were socialized to do the same for one another, offering words of encouragement and sometimes getting off their own bikes to run alongside slower riders, cheering them on as they struggled to climb steep hills.

Notably, it wasn’t just the fast riders cheering on the slow riders; the slow riders reciprocated. Through this near-constant cheering and mutual support, organizers and participants enacted a culture of caring that reflected, in the words of one organizer, “the way the world should be.” At the Closing Ceremonies, one speaker urged: “Don’t just remember what you’ve experienced these six days and leave the spirit of caring and love behind you. Bring that caring spirit to the rest of the world. Help make the rest of the world more like ACT II.”

What did all of this accomplish? ACT II ultimately achieved the three main goals of all fundraisers: it raised money, generated positive publicity, and recruited volunteers for the organization and its cause. Because ACT II provided participants with an experience more meaningful and rewarding than putting a stamp on an envelope, more than a few ACT II participants remained dedicated volunteers, participating in ACT rides year after year. Of course, our ride didn’t win the fight against HIV/AIDS, but it did teach us a lesson: each of us can make a difference through hard work and determination. Horatio Alger would be proud.

the politics of fun

The emergence of fitness fundraisers and the broad appeal of civic recreation are inextricably bound with the economic, cultural, and political forces that have shaped our society over the past 50 years. This channeling of physical energy into civic purposes—this uniting of individual and social fitness—feels positive, proactive, and liberatory. It empowers people to take action, and it is more rewarding than writing a check. Civic recreation shows the tremendous creativity of nonprofit organizers and entrepreneurs working to create a better society any way they can. And it is liberating to know that civic action doesn’t have to be separated from ordinary life; it doesn’t have to be boring or overly serious. It doesn’t have to be anything. As our society changes, and as we seek new ways to improve it, we will adapt, innovate, and meet new challenges. That, at least, is the promise.

But then I think about playing kickball for Tibet, and it all seems ludicrous. Civic recreation can make politics seem a little too easy, a little too fun—just another commodity to be consumed and enjoyed without any deeper investment or risk. Even worse, cloaking politics in a mantle of sports and recreation could simply be “producing apathy,” as political ethnographer Nina Eliasoph might put it. It may be comforting to think that one form of civic engagement is just as good as another, but succumbing to the politics of fun risks making us unable or unwilling to do the important work when it’s not fun. Critics are right to worry whether we will work as good citizens for the common good, if it does not benefit—or entertain—us directly. Politics can be a matter of life and death—maybe not for you today, but for someone somewhere.

In the end, I think of civic recreation as the knife-edge of democracy. On one hand, civic recreation amplifies the self-interested individualism generated by the fitness boom and the conservative shift in U.S. politics. On the other hand, it is a product of the “rights revolution” of the 1960s, and it shows—directly and experientially—some of the important ways that the personal is political. Just as civic recreation can lead us into mindless consumption or political apathy, it can empower us to take action of the most communal and political sort. The promise of democracy stretches deep, deep down into the minutiae of everyday life; the means and ends to which we devote our civic energies are up to us. So, too, for civic recreation: its social benefits are there to be claimed, but are not guaranteed.

recommended readings

Eliasoph, Nina. Avoiding Politics: How Americans Produce Apathy in Everyday Life (Cambridge University Press, 1998). An innovative ethnography of the ways people use informal talk and recreation to empty the public sphere of political discourse.

King, Samantha. Pink Ribbons, Inc.: Breast Cancer and the Politics of Philanthropy (University of Minnesota Press, 2006). A strong critique of corporate philanthropy, cause marketing, and other ways the line between charity and profit is being blurred.

National Center for Charitable Statistics. One of the best online sources of data on the nonprofit sector, with integrated tools for conducting analyses.

Putnam, Robert D. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community (Simon & Schuster, 2000). A powerful description and explanation of trends in civic participation and social capital in the U.S. in the late 20th century.

Schudson, Michael. The Good Citizen: A History of American Civic Life (Martin Kessler Books, 1998). An insightful historical analysis of how the meanings of citizenship have changed in the U.S. since the colonial era.

Comments 1

Dan Pallotta

December 12, 2011Peter - you got your facts all wrong. Visit http://www.pallottateamworks.com and you'll see that the events continued to net more money each year - $77 million in 2002 - a feat no one has replicated. Thanks.