Lesbian Geographies

When we think about gay neighborhoods, many of us are not immediately imagining lesbians. But like gay men, lesbians also have certain cities, neighborhoods, and small towns in which they are more likely to live. Back in 1992, for example, the National Enquirer cheekily declared the small town of Northampton, Mass. “Lesbianville, USA.” Newsweek piggybacked on the reference a year later and sealed the area’s Sapphic reputation: “If you’re looking for lesbians, they’re everywhere,” said Diane Morgan, who used to codirect an annual summer festival that drew thousands of women. “After living here for a couple years, you begin to forget what it’s like in the real world.” The bucolic town—“where the coffee is strong and so are the women”—had a lesbian mayor, Mary Clare Higgins, who held a near-record tenure of political office—six consecutive two-year terms.

If Northampton is the Lesbianville of the Northeast, then Portland, Ore. and Oakland, Calif. are the lady-loving capitals of the West, while Atlanta, Ga. and St. Petersburg, Fla. remain hot in the Southern imagination. And let us not forget about Park Slope in Brooklyn: “Being a dyke and living in the Slope is like being a gay man and living in the Village,” one resident remarked to geographer Tamar Rothenberg. In recent years, New York City has also seen an influx of lesbians in Kensington, Red Hook, and Harlem.

There is an astonishing diversity of queer spaces for men and women alike, as Census data on zip codes shows us.

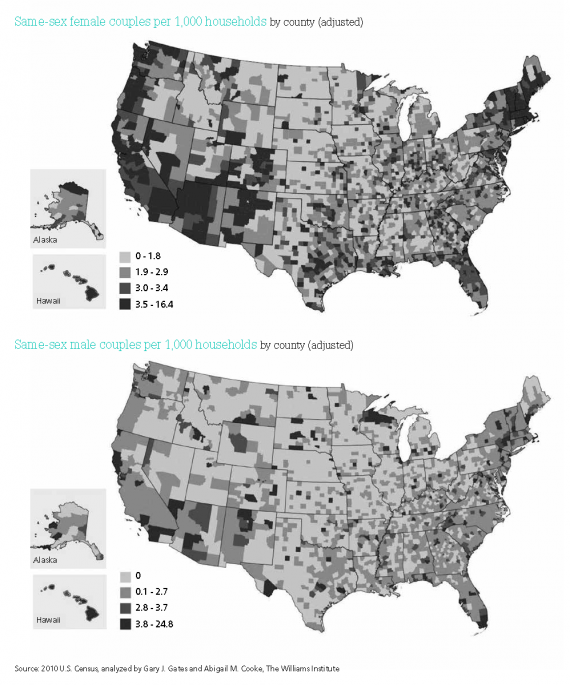

Sometimes lesbians live in the same areas as gay men, like Provincetown, Mass., Rehoboth Beach, Del., and the Castro in San Francisco, Calif. But lesbian geographies are also quite distinct. Coupled women tend to live in less urban areas, while men opt for bigger cities (regrettably, the Census only asks about same-sex partner households, and so we cannot track single gays and lesbians). We do not have a good grasp on why this happens, but cultural cues regarding masculinity and femininity play a part. One rural, gay Midwesterner confided to sociologist Emily Kazyak: “If you’re a flaming gay queen, they’re like, ‘Oh, you’re a freak, I’m scared of you.’ But if you’re a really butch woman and you’re working at a factory, I think it’s a little easier.” Lesbians who perform masculinity in rural environments (by working hard labor or acting tough, for example) are not as stigmatized as effeminate gay men. This makes rural contexts safer and more inviting for women.

Concerns about family formation and childrearing come into play as well. According to an analysis by the Williams Institute, a think tank at UCLA, more than 111,000 same-sex couples are raising 170,000 biological, step, or adopted children. There are some striking gender differences within this group. For instance, among those individuals who are younger than 50 and living alone or with a partner, nearly half of LGBT women (48%) and a fifth of LGBT men (20%) are raising a child under the age of 18. Among couple households, specifically, 27% of female and 11% of male couples are raising children. Finally, among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults who report ever having given birth to or fathered a child, 80% are female. All these numbers tell us the same thing: lesbians are more likely than gay men to have and raise children.

Higher rates of parenting by lesbians create different housing needs for them. Traditional gay neighborhoods are more likely to offer single-occupancy apartments at relatively high rents, but lesbian households with children seek the reverse: lower-rent, more family-oriented units. This steers women either to different neighborhoods in the same city (Andersonville or Rogers Park rather than Boystown in Chicago for example, or Oakland instead of the Castro in San Francisco), or to non-urban areas, as we can see in the earlier table and graphics below.

Back in the city, lesbians exert a surprising influence on cycles of gentrification. The idea that gay people initiate renewal efforts is widely known but imprecise. Lesbians actually predate the arrival of gay men in developing areas. A 2010 New York Observer article put it this way: “[L]esbians are handy urban pioneers, dragging organic groceries and prenatal yoga to the ‘frontier’ neighborhoods they make hospitable for the rest of us. In three to five years.” Lesbians move in first—they are “canaries in the urban coal mine”—and try to create a space for themselves. Gay men arrive next as they are priced out of previous enclaves. According to a 2013 Trulia report, “Neighborhoods where same-sex male couples account for more than one percent of all households (that’s three times the national average) had price increases, on average, of 13.8%. In neighborhoods where same-sex female couples account for more than one percent of all households, prices increased by 16.5%—more than one-and-a-half times the national increase.” As a point of comparison, the overall national increase for urban and suburban neighborhoods was 10.5%. Basically, the gayer the block, the faster its values will rise. Lesbian neighborhoods experience greater increases probably because they are in earlier stages of gentrification, further from a ceiling where prices eventually plateau, and because they had lower values from the start.

Gay men follow the trailblazing lesbians (awareness of where the women are circulates by word of mouth). As the numbers of men increase, the identity of the area gradually shifts from a lesbian enclave to a “gayborhood.” During this transition, the composition of the district where the men previously lived becomes demographically straighter. Meanwhile, the texture of the new area becomes gayer and increasingly dominated by men. Many lesbians feel priced-out at this point, and they migrate elsewhere, initiating another round of renewal.

Subcultural differences also help explain why it is harder to find lesbian lands. Gay men are more influenced by sexual transactions and building commercial institutions like bars, big night clubs, saunas, and trendy restaurants, while gay women are motivated by feminism and countercultures. This is why lesbian neighborhoods often consist of a cluster of homes near progressive, though not as flashy, organizations and businesses that were already based in the area—think artsy theaters and performance spaces, alternative or secondhand bookstores, cafes, community centers, bike shops, and organic or cooperative grocery stores. This gives lesbian districts a quasi-underground character, making them seem hidden for those who are not in the know.

But this begs us to ask another question: why, after gay men arrive, do some lesbians leave? One reason pertains to women’s relative lack of economic power. Real estate values and rents continue to increase as more gay men arrive. Although the gender wage gap (women’s earnings as a percentage of men’s) has narrowed, according to the US Labor Department’s Bureau of Labor Statistics, women still earn, on average, less than men—81% of what men earned in 2012. This persistent economic inequality explains why lesbian households are located in lower-income areas, and unfortunately, such material threats are always encroaching on them.

Finally, some lesbians move out because they perceive the area as unwelcoming after the male invasion. Gay men are still men, after all, and they are not exempt from the sexism that saturates our society. In reflecting on her experiences in the gay village of Manchester, England, one lesbian described gay men as “quite intimidating. They’re not very welcoming towards women.” Similarly, a lesbian from Chicago told me: “Boystown is a gay neighborhood. It’s boys’ town—it’s all guys. Boystown is super, super male. Andersonville is definitely more lesbian… It’s very female-oriented. It’s lesbian.” Indeed, some women refer to Andersonville as “Girlstown,” “the lesbian ghetto,” or “Dykeville.” Although gay men and straight newcomers often arrive at about the same time, some lesbians feel especially resentful toward the former. Another woman from Chicago vented, “The straight couples are guests in our community. The gay men are coming to pillage. Imperialism is coming up from Boystown.”

What does all of this mean? Jim Owles of the New York Gay Activist Alliance said in 1971 that “one of society’s favorite myths about gay people is that we are all alike.” More than forty years have passed, but the myth is still hard to shake. Our ideas about a gay neighborhood rely on a fairly unimaginative and singular understanding of queer life and culture, making it much harder for us to see and appreciate unique lesbian geographies.