CSPAN screenshot via Washington Post.

Not a Snowball’s Chance for Science

Senator James Inhofe of Oklahoma wrote the book on climate science denial, literally. He titled it The Greatest Hoax, and in it he slaps the label “alarmist” onto the thousands of geologists, hydrologists, and atmospheric scientists worldwide who argue that climate change is a human-driven phenomenon with dire consequences for the health and habitability of this planet. At the same time, he uses the book to laud the “bravery” of the handful of contrarian scientists who support his perspective that a changing climate is neither caused by human action, nor especially threatening to human life. So it isn’t surprising that, in February of 2015, Senator Inhofe—newly named Chairman of the Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works—brought a snowball to the floor of the U.S. Congress. That snowball, Inhofe argued, was all he needed to demonstrate that climate change is a fraud.

“In case we have forgotten,” he said with a flourish, “because we keep hearing that 2014 has been the warmest year on record, I ask the Chair, you know what this is? It’s a snowball. And that’s just from outside here. So it’s very, very cold out.”

Via ABC Politics, Vine. https://vine.co/v/O2J1F0lYIeY

To answer these questions, we have used social network analysis to dissect what we call the “elite climate policy network” in the U.S. Using data collected from a survey of the politicians, federal agency workers, business leaders, activists, and scientists most engaged in American climate politics, we demonstrate that it is the unique shape of the relationships among these “policy actors” that has distorted the message of consensus science. This shape—an echo chamber—has intensified debate by amplifying marginal opinions and keeping misinformation in circulation.

In the summer of 2010, our research team approached the top 100 policy actors engaged in climate change politics and asked them to participate in our study—to be surveyed and interviewed. This time was exceptionally active and contentious for U.S. climate politics. A bill to regulate carbon dioxide emissions had passed in the House of Representatives for the first time and a companion bill was being considered in the Senate. That summer remains the closest the U.S. has come to passing climate legislation at the federal level. The 64 policy actors who agreed to participate in our study had all been highly active in the climate policy arena: they had participated in numerous Congressional hearings related to climate science and policy, and many had attended the international climate negotiations in Copenhagen in 2009, which had been expected to yield an updated international climate treaty. From these data, we saw the emergence of an echo chamber (technical details and more background are in our paper just published in Nature Climate Change).

Who You Know (and Who They Know)

Social network analysis enables us to look at how people are connected. We asked respondents whom they saw as their sources of “expert scientific information,” providing each with a list of the 100 policy actors and asking them to check off every office, institution, business, or individual they considered one of their expert sources of scientific information. By using a method called Exponential Random Graph modeling, or ERGM, we were able to look at how information flows within and throughout this climate policy network. We were also able to isolate the influence of specific relationships, such as the echo chamber, within the entire network.

The Echo and the Chamber

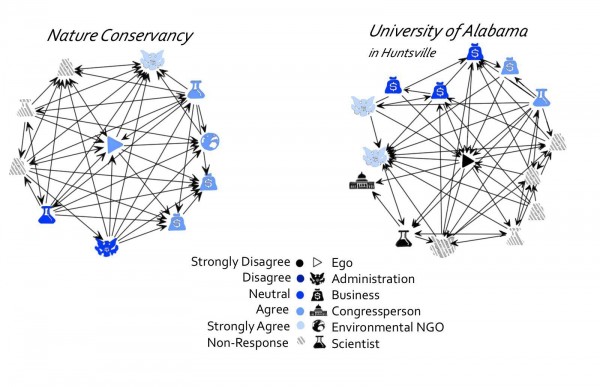

This belief agreement is what we call the echo. The figures below show the individual networks of two respondents in our sample—the Nature Conservancy and a scientist at the University of Alabama–Huntsville who has frequently testified in Congressional hearings about climate science. These “ego networks” represent the specific part of the network made up of a single actor, or ego, and everyone tied to that individual. An ego network is like the ego’s neighborhood: it contains everyone who sends information to or receives information from the ego, as well as all the ties among those actors. The arrows point in the direction of information flow.

Nodes in each network are shaded based on how they responded to the statement, “There should be an international binding commitment on all nations to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.” This statement represents an issue of contention in American climate politics since the mid-1990s (that’s when the Senate unanimously passed the Byrd-Hagel Resolution, limiting the Clinton Administration’s ability to negotiate for an international climate treaty). Black indicates strong disagreement, and light gray indicates strong agreement (the grayed markers indicate a non-response to the question about an international binding agreement).

The ego-networks for both actors illustrate that they have a diversity of political actors in their networks—they listed many sources of information, and they were, in turn, listed as sources by many others. We also see strong patterns in issue agreement and information flow. For example, the Nature Conservancy is an environmentally focused non-governmental organization that regularly lobbies for environmental protections at the federal level. Most of their contacts agreed with the statement, and none disagreed. These findings are consistent among all of our respondents: policy actors reliably cited sources who held the same ideological position as they did.

In addition to these actors getting their information from those who already share the same opinions, the information is also amplified when it is transmitted through multiple pathways. These pathways describe our metaphorical chamber mechanism. In social network analysis, this mechanism is also known as the “transitive triad.” A transitive triad is a group of three actors in which one individual is the source of information and transmits information to a second person both directly and indirectly through the third person. In other words, the same information gets diffused directly and indirectly through intermediary actors repeating that same information. Note that, from the perspective of the person receiving the information, this information appears to be coming from multiple sources, though, in fact, it is coming from a single source.

The scientist from the University of Alabama, who strongly disagrees that there should be a binding commitment to reduce carbon dioxide, has one echo chamber in his network: he transmits information to a scientist and to the office of Senator Inhofe (the Congressperson in his network). The other scientist also transmits information to Inhofe, and because they all disagree with a binding greenhouse gas commitment, they form an echo chamber. We can see a number of echo chambers within the Nature Conservancy’s ego network as well, as this group passes on information directly and indirectly to other actors that agree that there should be a binding commitment to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

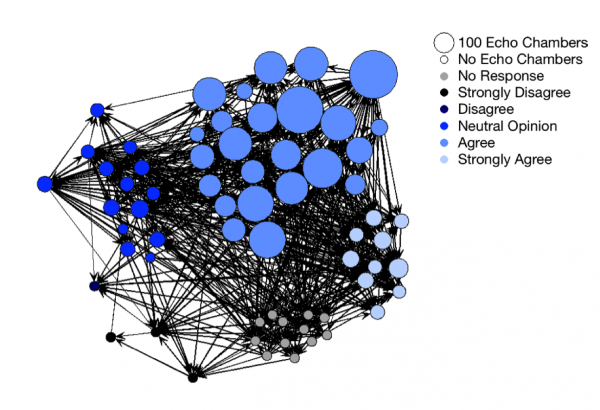

The network graph below presents the entire network of respondents. The nodes are again shaded based on their responses to the question about whether there should be a binding agreement on climate change. The size of the nodes is reflective of the number of echo chambers—transitive triads among actors with the same ideological position—in which each actor is engaged. The possible number of echo chambers for each ideological category is, of course, related to the number of respondents in each category; the respondents with the most echo chambers also display the most popular viewpoint.

Echo chambers can occur randomly in a network. Imagine an alternative network where we randomly assign the same number of connections among the policy actors and the same distribution of attitudes that we found in our survey. In such an alternative network, we could observe some echo chambers due to chance alone. We use ERGM to test our results and see if the presence of echo chambers in these findings can be explained by random chance or a combination of other possible network structures and attributes. ERGM enables us to simulate hundreds of thousands of alternate networks to estimate how important the echo chambers are in modeling our data.

Politics in the Echo Chamber

The results of our analysis show that echo chambers occur in our network more often than random chance or the other characteristics of the network would predict. Furthermore, the ERGM shows that chambers of agreement among political elites—the transitive triads—do not exist significantly outside those who agree to the attitudinal questions about climate politics. Together, these findings confirm that echo chambers have formed in the U.S. climate policy network.

Our analysis also found that scientific actors and those from the Executive Branch of the government were more frequently cited as sources of information than business organizations. Although it is encouraging that science is widely cited as a source of information on climate change in our network, we return now to the question of how scientific consensus can be so hotly contested in the political sphere.

When James Inhofe brought a snowball to the floor of the U.S. Senate, he was expressing more than the temperature of Washington, D.C. in February. He was demonstrating politics in an echo chamber: the particular networks in which Inhofe—and all political elites—operate make it not only possible to assert that snow equals science, but it also makes such claims plausible. The combination of ideological homophily and closed communication structures make arguments like this compelling for those who already agree with the position, but baffling for everyone outside the echo chamber.

The Future of Science and Politics

These findings are telling for the science communication process. It seems that climate science is more beholden to politics than politics is to the actual science. In the political arena, echo chambers structure how climate science is discussed, perceived, accepted, or dismissed by different political actors. Rather than discussing a single scientific consensus position, political actors can cherry-pick exactly which parts of the science they wish to amplify or undermine. Echo chambers provide the perfect environment for such a selective discussion of scientific facts.

The onus of breaking the echo chamber, then, is borne by those who advocate for greater scientific literacy in policymaking. Climate activists, and even scientists themselves, must be prepared to facilitate discussion among policy actors with diverging ideological views on climate change in order to break apart these echo chambers. Furthermore, these opportunities for discussion should come as early as possible in the political process, perhaps even preceding the information-gathering stage. For issues as long-fought as climate change, it may be too late. But avoiding the persistent effects of echo chambers in other political issues may still be possible where the debate is young.

This research also shows that responsible citizens must be careful with our own sources of scientific information if we want to ensure that our perception on any issue is accurate. Although the data here are gathered from political elites, echo chambers have important implications for information transmission in our own lives. We face the same potential problems of cherry-picked information in our day-to-day routines as we turn to specific sources for information. As other researchers have noted, the online social media environment accentuates such echo chambers as we are able to create increasingly personalized media profiles. Such “narrow-casting” can lead to echo chambers that distort our own perception of the risks, responsibilities, and opportunities present in political and policy issues.

Recommended Resources

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). 2014. Fifth Assessment Report. Available at ipcc.ch/report/ar5. An overview of the current state of peer-reviewed climate change science.

Dana R. Fisher, Joseph Waggle, and Philip Leifeld. 2013. “Where Does Political Polarization Come From? Locating Polarization with the US Climate Change Debate,” American Behavioral Scientist 57(1):70-92. An empirical demonstration that political polarization around climate change does not stem from disagreements about science, but from disagreements on the policy instruments proposed to address the issue.

Linton Freeman. 2004. The Development of Social Network Analysis: A Study in the Sociology of Science. North Charleston, SC: Book Surge LLC. An accessible and concise history analysis and its applications in the social sciences.

Lorien Jasny, Joseph Waggle, and Dana R. Fisher. 2015. “An Empirical Examination of Echo Chambers in US Climate Policy Networks.” Nature Climate Change 5:782-786. Employs social network analysis to show that echo chambers are present in U.S. climate politics and they transmit distorted scientific information throughout the policymaking process.

Naomi Oreskes and Erik M. Conway. 2010. Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming. New York: Bloomsbury Press. Uses politically and scientifically charged case studies to demonstrate how scientific expertise and the political process can help and hinder one another.

Comments 3

Letta Page

November 24, 2015Amazing to see how these echo chambers carry into other areas of public life through policymaking -- Gawker just posted an article today on content analysis out of Stanford showing that California public school textbooks ape the language of climate change denial: http://gawker.com/study-california-textbooks-are-completely-misleading-a-1744317212?sidebar_promotions_icons=testingoff&utm_expid=66866090-67.e9PWeE2DSnKObFD7vNEoqg.1&utm_referrer=http%3A%2F%2Fgawker.com%2F

John Mashey

December 7, 2015Nice Work! I applaud more social scientists getting involved with this area.

You may find some more history useful regarding the snowball session in the Senate:

http://www.desmogblog.com/2015/01/26/medievaldeception-2015-inhofe-drags-senate-dark-ages

Publishing Is Not Enough: Quit Being so Homophilic | Beachfront Media

December 16, 2015[…] “network homophily”. The publication Contexts was exploring this idea when they wrote about the divide between science and politics, while even more recently, Fortune had a really great article on the communicative divide over […]