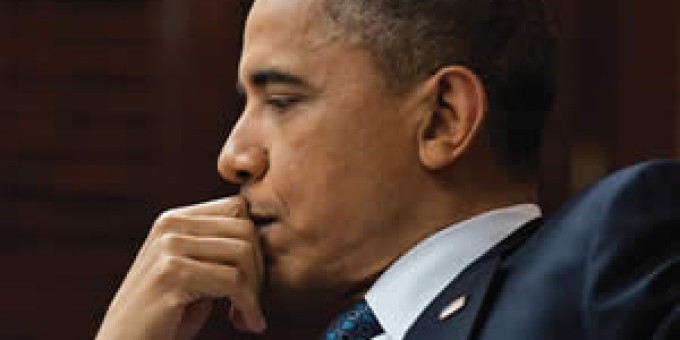

Judging Obama

In 2008, the media hailed the coming of an “Obama Revolution.” Four years later, commentators on both the left and right are disappointed, to say the least.

Viewed from a longer historical perspective, however, the significance of the Obama presidency is difficult to deny. The rise of an African American with a humble background to become the President in a landslide victory, winning even many traditionally Republican areas, is no small thing.

The Obama presidency symbolically reinstated American meritocratic ideals. This is particularly remarkable as it happened just four years after the 2004 election, during which the Skulls and Bones memberships of George W. Bush and John Kerry, as well as that of many other senior political, military, and corporate leaders, led to a public outcry over the transition to aristocracy in America. C. Wright Mills’ The Power Elite celebrated its 50th anniversary in 2006. The revival of Mills’ dark view of American politics alarmed the power elite at the time, so much so that Playboy ran an unusually serious commentary “Who Rules America?” by long-time political insider Arthur Schlesinger Jr., accusing Mills of conspiracy-mongering.

The symbolism of Obama is not without real consequence. For example, criminologist Randolph Roth noted an “Obama effect” that reinvigorated African Americans’ trust in the political process and helped explain the puzzlingly sharp drop in urban violence in early 2009. The Obama presidency also brought real reform, most notably in healthcare—”one of the most equality-promoting pieces of social legislation ever enacted in the U.S.,” according to sociologist Theda Skocpol.

To be sure, the Obama presidency is not going to be evaluated by its symbolic significance and by healthcare reform alone. In 2008, candidate Obama promised to retool the U.S. economy into a green, productive one freed from dependency on financial speculation and foreign oil, to reform the dysfunctional immigration regime, and to mend America’s relationship with the world which had been strained by his predecessor’s militarist approach to world affairs.

This symposium places Obama’s first term in context, assesses its outcomes, and explores the road forward. In what follows, Fred Block deciphers the forgotten achievements of Obama’s administration in “greening” the U.S. economy, Alejandro Portes diagnoses the impasse of immigration reform, Beverly J. Silver discusses Obama’s dilemma in repositioning the United States in the world, and Richard Lachmann explores how Obama could overcome structural constraints and advance his reforms. These commentaries add invaluable perspectives to the public discourse about the Obama presidency, which is set to intensify during this election year.

— Ho-Fung Hung

- Green Energy, by Fred Block

- Stalled Immigration Reform, by Alejandro Portes

- Superpower Blues, by Beverly J. Silver

- Between a Rock and a Hard Place, by Richard Lachmann

Green Energy

by Fred Block

The conventional wisdom among both pundits and social scientists is that the Obama administration has let a good crisis go to waste. They argue that the administration did not take advantage of the economic crisis in 2009; the stimulus measure was too small and too focused on tax cuts and other short-term measures to drive a strong recovery from the recession.

But this argument overlooks tens of billions of stimulus dollars that the Department of Energy (DOE) used to accelerate both the development and deployment of a wide range of clean energy technologies. While largely ignored by the news media except when there are hints of potential scandal, the DOE effort represents one of the largest governmental initiatives to rebuild a critical part of the nation’s civilian infrastructure in the nation’s history, paralleling the construction of the intercontinental railroad under Lincoln and the building of the interstate highway under Eisenhower.

Over the last three decades the federal government has developed sophisticated systems to move hundreds of new technologies from laboratories to the marketplace. Since the 1980s, the DOE has become increasingly skillful in nurturing new technologies and supporting the firms that commercialize them. Yet, the frequent pattern has been that U.S. public-private partnerships would pioneer major technological advances— the Internet, solar cells, and flat panel displays — but other nations would soon leap ahead because their governments were willing to invest the funds needed to support mass deployment or efficient mass production.Obama’s DOE chose to break with this pattern through a multi-pronged initiative designed to accomplish several goals simultaneously: accelerate technological advances that would make clean energy technologies price competitive with coal and oil, establish powerful incentives to increase deployment of clean energy technologies across the entire economy, and rebuild U.S. manufacturing capacity for critical industries such as plug-in hybrid electric cars, advanced batteries, solar panels, and wind turbines.

To accomplish these ends, the DOE has used a wide variety of different instruments. The government has provided $25.6 billion in loan guarantees to private firms to develop wind, geothermal, and solar energy and to support the production of electric vehicles. While the failed loan to Solyndra has gotten huge amounts of press coverage, most of these loans are sound. Many have gone to utility-scale generating projects where developers have been able to sign contracts with utilities to sell clean energy for the next thirty years.

The DOE has also used refundable tax credits, grants, and government procurement to drive this process. In the case of the advanced batteries needed for plug-in cars, the government spent $1.5 billion on grants to help firms build factories to make the lithium-ion batteries. DOE also gave large grants to utility firms to start deploying smart meters to consumers— a critical step in building a smart electrical grid that can make effective use of wind and solar energy. The Department of Defense has also increased its clean energy initiatives, including converting military bases to solar power to boost demand for U.S. produced solar panels.

The logic behind all of these efforts is that expanded production and deployment will push down costs to a point where significant investments in clean energy solutions by businesses and households will rise dramatically, creating a virtuous cycle of falling costs and greater private investment. With some of these technologies, such as electric cars and the smart grid, it is too early to tell if the strategy is working, but with wind and solar, deployment has been rising, costs have been falling, and private firms are increasing their investments. The amount of newly installed solar photovoltaic capacity doubled in 2010 and then doubled again in 2011.

To be sure, these initiatives would have gained even greater momentum had Congress been able to pass a comprehensive energy bill that established durable incentives for alternative fuels. Moreover, Republican opposition and the exhaustion of stimulus funds threaten further progress. Even worse, the entrenched oil and coal industries have been attempting to reverse the green energy initiatives through aggressive lobbying and campaign contributions. But let it not be said that Obama’s Department of Energy wasted a crisis: the effort to shift this nation’s energy future has been nothing short of heroic.

Stalled Immigration Reform

by Alejandro Portes

The peculiar disconnect in immigration features a permanent need for foreign workers in labor intensive sectors of the American economy—such as agriculture, construction, and personal services—coupled with shrill nativist campaigns against the same workers. In the absence of a legal and flexible temporary labor program, Mexican and Central American peasants and workers have responded to the jobs available in the U.S. side by migrating clandestinely, resulting in an informal “system” of cyclical labor migration with unauthorized workers harvesting crops or filling other temporary jobs and then returning home.

The increasingly strident nativist campaign against this system led the federal government to respond not by creating a regular temporary labor program, but by militarizing the border. By 2005, the Border Patrol had become the largest arms-bearing agency of the federal government, except for the military itself. This policy did not stem clandestine migration but channeled it into new directions. With traditional border-crossing spots in or near urban areas closed, the flow shifted to the Arizona desert and other remote areas. This Bush-era border enforcement campaign fostered a huge caste-like population of disenfranchised migrant workers in American territory. The Bush administration sought, at first, to regularize the situation through comprehensive immigration reform. After that plan failed in Congress due to fierce opposition from the president’s own party, the administration shifted to repression. Under the guise of protecting the country against terrorists, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), an agency of Homeland Security, launched a nationwide deportation campaign against unauthorized immigrants. Even though no single Mexican migrant worker has ever been convicted of terrorist intentions, the campaign focused squarely on Mexican unauthorized workers, splitting families, leaving children stranded, and causing untold misery.The ICE campaign drove the immigrant population further underground. This was the situation that the new administration confronted in 2008, and President Obama promised to fix this broken system through comprehensive immigration reform. Nothing of the sort has happened. On the contrary, the deportation campaign continued and even accelerated after 2008, and further expansions of the Border Patrol were put into place.

Obama’s failure to implement immigration reform so far has been due to a number of reasons: the need to cope with the catastrophic economic situation inherited from the Republicans; the decision to invest political capital to bring about reform of the health system; and finally, the consistent intransigence of Republicans in Congress to any attempt to bring the unauthorized population above ground through some form of regularization.

Meanwhile, the rapid decline in job opportunities brought about by the Great Recession and the relative improvement in Mexico’s economy have significantly reduced unauthorized migration from that country. Border apprehensions have dropped sharply during the last three years, and now number less than a third of what they were just a decade ago. Nativists and conservatives continue to rally against a threat that has become increasingly imaginary. The real threat at present is to American agriculture, with farmers’ organizations loudly complaining about crops rotting in the fields due to the lack of migrant labor. These complaints have been particularly strong in states like Arizona, where economic decline has been met with harsh anti-immigrant measures.

With migrant and Hispanic organizations orchestrating massive protests against the continuing ICE deportation campaign in the Fall of 2011, the administration, perceiving a direct threat to its Hispanic support base in the forthcoming presidential election, backtracked, seeking to put the campaign on hold. Thereafter, only aliens with a criminal record would face deportation and their situations would be reviewed on a case-by-case basis. In response to the outcry for new workers from American farmers, the administration also substantially expanded the H2-A visa program for agricultural migrant labor.

Superpower Blues

by Beverly J. Silver

A key issue facing the United States in the coming years will be how to adjust to a world in which it is no longer the world’s sole superpower. At the outset of the Bush administration, the belief that U.S. global dominance would continue well into the twenty-first century was widespread. But the perception of continued U.S. dominance rested as much on the weakness of others—ranging from the 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union to the 1997 East Asian financial crisis—as on the strength of the United States. The result was a gross overestimation of the extent and nature of U.S. world power, which fed the unilateralism and arrogance of the Bush administration—a “you are with us or against us” attitude. By the time Barack Obama reached the presidency, the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan had become quagmires, friends and allies around the world had been alienated, the United States had become both the epicenter of a major financial meltdown, and the world’s largest debtor nation, dependent on an enormous inflow of funds borrowed from abroad.

Notwithstanding Obama’s substantial diplomatic success in repairing frayed relations with allies, evidence of the limits of U.S. power has continued to mount. Indeed, by the end of 2011, talk of U.S. decline became widespread among scholars and pundits across the political spectrum. Standard and Poor’s downgrading of U.S. Treasury Bonds and the related Congressional impasse over the debt ceiling raised the specter of a voluntary default on the country’s international obligations, dramatizing the shaky foundations of U.S. economic power. Ongoing rapid economic growth in China and much of the “Global South,” combined with stagnation in the United States has translated into a relative decline in the weight of the United States in the global economy. Meanwhile, the Obama administration’s inability to find a winning strategy in Afghanistan is again illustrating the limits of U.S. military power.

While some have argued that a graceful adjustment to a multilateral world would be the best U.S. strategy, the Obama administration has made clear that, at least for now, adjustment to relative decline is not on its agenda. In his 2012 State of the Union address, Obama took a page (literally) from a recent article in The New Republic by Robert Kagan, a Mitt Romney advisor and co-founder of the Bush-era Project for a New American Century: “America is back,” Obama declared; “Anyone who tells you that America is in decline or that our influence has waned, doesn’t know what they’re talking about.” Hillary Clinton’s recent article in Foreign Policy, published under the title “America’s Pacific Century,” describes plans for a “strategic pivot” towards the Asia Pacific region including taking an active role in policing the South China Sea. Clinton declared: “there should be no doubt that America has the capacity to secure and sustain our global leadership in this century as we did in the last.”

To be sure, campaign dynamics are at work here as Obama seeks to insulate himself from claims (such as Romney’s) that he is “surrendering America’s role in the world” as the “strongest nation on Earth.” But it also tells us that the positions any president can take are extremely limited and increasingly unrealistic. There are deep-seated reasons for this myopia, such as the attachment of U.S. citizens to the idea of being “top dog” in a global status hierarchy, and the actual and perceived benefits accruing to groups and individuals from U.S. military spending. Serious efforts to fully understand the causes of this myopia are crucial. Our inability to discuss, much less act upon, the changing U.S. position in the world is deeply worrying.

As John Maynard Keynes partly foresaw in his 1919 The Economic Consequences of the Peace (and as Giovanni Arrighi and I argued in Chaos and Governance in the Modern World System), British world hegemony came to an earlier and far more catastrophic end — for Britain and the world — because Britain expanded and tightened its grip on Empire in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century, rather than adjust to a changing balance of world power. There is no predetermined reason why the United States should follow the same path. But, as long as being anything less than “Number 1” in the world is perceived as an unthinkable existential threat, there is a strong chance that the actions of the United States will end up contributing to growing disorder and suffering rather than to a more peaceful and equitable world order.

Between a Rock and a Hard Place

by Richard Lachmann

The 2012 election will determine whether or not America reverts to and then intensifies decades of conservative policies by electing a Republican president. If President Obama is re-elected, he could deepen progressive reform or acquiesce to the efforts of special interests to undermine that potential.

The choices are so stark because most of President Obama’s reforms have yet to be institutionalized, and could quickly be reversed by a Republican administration. His plans to transform health care, energy, education, social welfare, and industrial policy all depend on the sustained use of a president’s regulatory power. In each policy domain, Obama bowed to the power of corporate interests. In his healthcare legislation, hospitals, physicians, pharmaceutical companies, and above all, insurance corporations were guaranteed continued control of their markets. They traded small reductions in profit margins for federal subsidies that promised to turn millions of the uninsured into new customers.

The one realm of drastic reform has been the college loan program: Obama was able to push through legislation to eliminate subsidies for banks that made student loans guaranteed entirely by the federal government. The legislation used the savings to increase loan amounts for students. That success was possible only because private banks had withdrawn from the student loan market in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. At the elementary and secondary levels, Obama’s “Race to the Top” incentives have drastically increased student testing, which is then used to evaluate teachers. That program does not challenge corporate interests. Rather, it pushes states to implement the pet theories of wealthy philanthropists over the objections of teachers’ unions.

Why has President Obama not been more aggressive in challenging special interests? The dominant explanation, from journalists and political rivals, is profoundly unsociological, seeing policy as a matter of the president’s psyche, and any shortcomings as a result of his lack of assertiveness, a deep psychological need to find compromise, or too much faith in the judgment of highly credentialed advisors. In fact, even a more aggressive and assertive president could not have accomplished significantly more, given the weakness of labor unions and other progressive organizations, as well as legislators’ reliance on corporate donors and the very wealthy who carefully track congressional votes on legislation that directly affect their interests.What choices are there? The 2012 election will determine if the reforms President Obama initiated will be sustained. If a Republican wins, the health care reform will be undone, the student loan program will almost certainly be privatized again, and other modest reforms will be reversed as well. But even if Obama is re-elected, the possibilities of further reform are uncertain. Budgetary pressures will remain. Republicans will continue to obstruct Congress. Under such constraints, Obama could follow Clinton’s post-1994 approach: collaborating with a Republican Congress to enact petty programs, and rewarding special interests with further deregulation.

The one power open to a re-elected President Obama is the vast regulatory authority the president’s office has accumulated over decades. Obama’s health care legislation significantly expanded the already substantial federal regulation over that sector. Through the Environmental Protection Agency, Obama has the power to regulate greenhouse gases and thus by fiat impose a conversion to green energy. Obama could expand on the very modest limits recently imposed on for-profit colleges and trade schools, making even more funds available for students to attend public and non-profit universities. The list goes on.

Will Obama take the path of heightened regulation in a second term? To answer this question, we need to examine the political pressures that weigh even on a president who will never face the voters again. A re-elected Obama remains dependent on a Congress made up of members who still stand in future elections. The Democratic presidential candidate of 2016 will need contributions, and will pressure the Obama administration not to alienate potential corporate supporters.

And yet…popular protests could exert countervailing pressures. The Occupy movement has raised the issue of corporate power. The protesters could be effective to the extent they understand that the terrain of conflict in the next four years (assuming Obama’s re-election) will be over the promulgation of rules to regulate banks, health care companies, and to limit CO2 emissions. For social movements to have impact, they will need to track regulatory decisions and bring protesters into the streets at key moments. The protests in front of the White House in late 2011 against the Keystone Pipeline are a model. The skids had been greased for final approval of the pipeline. The protests ensured the postponement of the decision until at least 2013. Obama will take a progressive path in his second term only if protesters repeat that feat again and again.

Comments 2

MC

August 18, 2012Thank you for this article. I found especially Mr. Lachmann's piece insightful for essentially summing up my general feelings on this administration: it's been pretty mediocre, partly due to external barriers, but I'm not willing to entrust the executive to someone explicitly intent on reaction.

chris uggen

August 26, 2012a fascinating set of sociological perspectives -- thanks!