LGBTTSQQIAA…

Among the many valuable lessons that feminists of the 1970s and 1980s taught us was to watch our mouths—not in the way our parents might have told us to do, but because language matters. Terms like “womyn” and “wimmin” have fallen mostly by the wayside, but contemporary cultures carry the legacy of that feminist wisdom in words like “firefighter” and “police officer,” and in social psychological research showing that words do, in fact, make a difference in how we think about social roles. It was in this environment, and in response to tensions within the nascent gay liberation movement, that what some call the “alphabet soup” of contemporary sexual and gender identity terms first got its start. The full story, though, goes back much further.

The concepts of homosexuality and heterosexuality, as we know them today, were invented in the nineteenth century by practitioners of the new field of sexology. Influential sexologists such as Richard von Krafft-Ebing, Magnus Hirschfeld, and Albert Moll linked homosexuality to “sexual inversion,” suggesting that same-sex desire in the “true homosexual” resulted from a disjuncture between socially assigned gender and gender identity. This idea made its way into popular culture by the turn of the twentieth century. It would take another century, and a vibrant transgender rights movement, to begin to disentangle gender identity from sexual attraction in the popular imaginary.

As the concepts of homosexuality and inversion traveled from the realms of academic discourse to the popular sphere, and especially as people with nonconforming gender identities and/or same-sex desires encountered these terms, alternatives began to spring up. Some sexologists suggested terms like “urning” or “uranian” for men, drawn from a term for the Greek goddess Aphrodite. Though the parallel term “urningin” was developed for women, women came to be called (and sometimes to call themselves) “Sapphic” after the ancient Greek poet. The term “lesbian,” which derived from the name of Sappho’s home on the island of Lesbos, also developed during this time, as did the new use of the already-existent term “gay” to refer to same-sex attracted people, especially men.

While people with same-sex attractions and/or nonconforming gender identities sometimes used the term “homosexual” for themselves, they often sought alternative terms that bore fewer negative and clinical overtones. In the 1950s, U.S. activist Harry Hay suggested the word “homophile” in order to shift the terminological emphasis from sex In the 1960s, radical homosexuals began to use the term “gay.” to love, and the movements sparked or inspired by Hay in the 1950s and 1960s came to be known by this term. But when activist tactics shifted in a radical direction in these communities, one word came to the fore: gay.

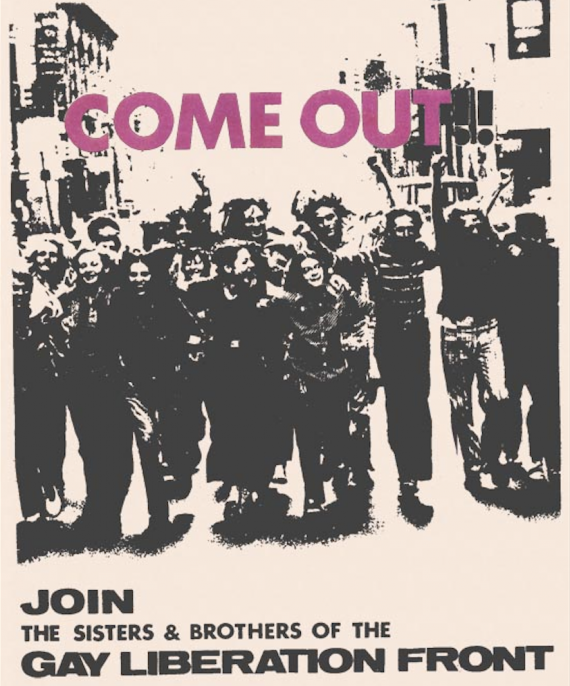

The radical activist organization that arose from the flames of New York’s Stonewall Riots in 1969 called itself the Gay Liberation Front, or GLF. At the time, although the term “bisexual” was known and used, and although some in the movement identified as transsexual and some would later come to identify as transgender, many in the movement were still more likely to call themselves “gay.” And so it seemed, for a brief moment and only to some, that there was one simple word by which to call same-sex-attracted and gender-nonconforming people.

Who’s In The Name

Within a few years of the GLF’s founding, it became clear to some of the women involved that “gay” might not really include them. Tired of facing sexism in the movement, and of being told that some of the issues they wanted to work on were “women’s issues” and not “gay issues,” women began to leave. Some, battling not only sexism in the GLF but also homophobia in the women’s movement, created their own space in lesbian feminism. These women made it clear that any movement or organization that truly intended to address the needs of same-sex attracted women as well as same-sex attracted men needed to include both in name as well as in intent. Thus, the 1980s in particular saw a growth in the use of the term “gay and lesbian,” or, to list the less socially empowered group first, “lesbian and gay.”

Also critical at this time in the movement was the power of naming to include or exclude U.S. people of color, and people from cultures other than the dominant U.S. mainstream. While some people from non-dominant cultures were involved in the gay rights movement, lesbian movements, and lesbian feminism, and while some actively chose the terms “gay” or “lesbian” for themselves for a variety of reasons, others preferred different terms. One example is the Two-Spirit movement, which grew in the early 1990s out of earlier organizations such as Gay American Indians. Because they wanted to work simultaneously on fighting settler colonialism and its effects, on strengthening traditional Native identities and knowledge around sexuality and gender, and on challenging contemporary resistance to those traditional identities in Native communities, the members of these organizations did not want simply to be a part of broader gay and lesbian activism. While some did, and some continue to, use terms such as “gay” or “lesbian” to refer to themselves, many have also or alternatively chosen terms from their own traditions or the pan-Indian term, Two-Spirit.

The move toward acknowledging lesbians’ choice of terminology, rather than subsuming everyone under the term “gay,” sparked further questions around inclusion. Bisexuals were the first to have their demands for inclusion answered in the affirmative, and over the course of the 1990s it became increasingly common to see or hear the term “gay, lesbian, and bisexual” as a description of a community or an organization. Some, unhappy with having to use three words and also dissatisfied with the new acronym (usually GLB), began to experiment with blended terms such as “lesbigay,” but before those terms could gain much of a foothold the names by which these communities were called changed again.

Distinguishing Gender Identity From Sexual Identity

Gender-nonconforming people, particularly those attracted to the same biological sex, had been a part of these movements from their earliest days, in part because of the fusion of sexual and gender identity in nineteenth and early twentieth-century concepts of homosexuality. When research on sex reassignment procedures began to take hold in Europe between the World Wars, a separate transsexual identity began to emerge. Because of the limited number of people who could access such procedures, however, and because of the rise of World War II and the subsequent cultural conformity in countries such as the United States, this identity sparked important local activism but did not yet result in a unified national or international movement. That movement began to coalesce by the end of the 1980s, under the term “transgender.” As the word has come to be used, “transgender” (some also use “trans,” or, more recently, “trans*”) encompasses a wide variety of identities and lived experiences, including those who choose (and have the resources) to alter their bodies hormonally and/or surgically, those who do not (or cannot) alter their bodies but whose everyday gender expression diverges from their socially-assigned gender, and those whose nonconforming gender presentation is more occasional than regular.

Because a number of people who came to claim transgender identities in the decades after the Stonewall Riots had at one time identified as gay, lesbian, or bisexual (and some continued to do so in addition to identifying as transgender), and because those outside of either trans-gender or LGB communities continue to assume an intrinsic connection between gender identities and sexual identities, transgender activists and lesbian, gay, and bisexual activists have found themselves in the same communities time and again. Sometimes the shared community results in alliance; more frequently, for transgender people, it has resulted in betrayal. The move to include transgender people in the increasingly-long acronym for these communities, then, held multiple meanings. On the one hand it was a gesture of inclusion, and an acknowledgement that transgender people are a part of these communities. On the other hand, to some transgender people the nominal inclusion seemed to be too little and too late. All too often, as happened frequently for bisexuals as well, an organization would add “the T” (or “the B”) to its name without actually shifting its policies, goals, vision, or practices to be more proactively inclusive.

Queering Or Reifying Identity?

Similar challenges arose with the term “queer.” Reclaimed from its derogatory past in the late 1980s by the activist group Queer Nation, the term was almost simultaneously but separately introduced into academia to prod what was then called “gay and lesbian studies” into greater inclusivity and a more radical analysis. “Queer” began its new life as a term connoting radical activism around sexual and gender identity; it also began as a term used mostly in white communities. By the early 2000s, though, “queer” had become less radical and more fashionably edgy, appropriate even for the title of a hit television show (Queer Eye for the Straight Guy). Yet, it also became the term of choice for a number of organizations founded by people of color, and the term “queer of color” began to appear commonly in the descriptions and names of organizations.

At the same time, it began to seem to some people that “queer” might be the answer to the growing difficulty of naming their community in fewer than ten syllables. By the early 2000s, acronyms often included not only gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender, but—among others—transsexual, Two-Spirit, asexual, ally, queer, questioning, and intersex (people born with ambiguous or mixed genitalia). Intersex activists, like transgender activists, disagreed about whether they were or wanted to be a part of this community, since their goals and priorities were different from those of the movement as a whole. The acronym had multiplied beyond expectation, yet even with all of this specificity not only were people still feeling left out, but some people were included who really did not want to be.

Interestingly, for those who chose it to name their identity, the strength of the term “queer” actually lay in its lack of specificity. Resistant to being “boxed in” yet also not willing to identify solely as heterosexual and/or as cisgender (that is, normatively gendered), some people chose “queer” because it expressed the fluidity they saw in their own sexual and gendered selves. The term “genderqueer,” for instance, came in the 2000s to indicate a gender identity that refused allegiance to either femininity or masculinity, expressing itself instead through nonconforming gender performances that resisted and confounded social assumptions about gender and anatomy. Likewise, some who claimed “queer” as a sexual identity refused the binary between “straight” and “gay,” and resisted the ways in which “bisexual” reinforced that binary. “Queer,” then, came for some to indicate sexual and gender identities that refused to conform with established gender or sexual identities in heterosexual, gay, lesbian, and cisgender cultures.

In the end, though, for a number of reasons “queer” failed to achieve full acceptance as the term of choice for all communities of gender-nonconforming and same-sex attracted people—this, despite its near-ubiquity among the members of Generation X and the Millennial generation. The most common term used today to describe same-sex attracted and gender non-conforming people is “LGBT” or “LGBTQ.” Where possible, though, many avoid the naming issue entirely now, preferring instead to refer simply to “sexual and gender identities.”