Ferguson and “Rapid-response” Teaching

Systematic racism was evident again late last summer in the now thoroughly media-covered shooting of an unarmed young Black man, Michael Brown, by a White police officer, Darren Wilson, in Ferguson, Missouri. The killing and the community’s response are rich with sociological issues: inequality and poverty, racial profiling, the militarization of the police, protester and police interaction, social media (#Ferguson and so-called hashtag activism), and the “criminalization of Black male youth”.

Ferguson was hit particularly hard by the recent recession. Its unemployment rates rose from 5 to 13%, worker earnings decreased by a third, and the number of households relying on federal housing assistance nearly tripled, according to a Brookings Institute analysis. By 2012, the rate of poverty in the population doubled to 25%. The community of Ferguson, one of many that have been disproportionally hurt by the economic downturn, has experienced long-term poverty, and this was undoubtedly part of the mass frustration that contributed to protests.

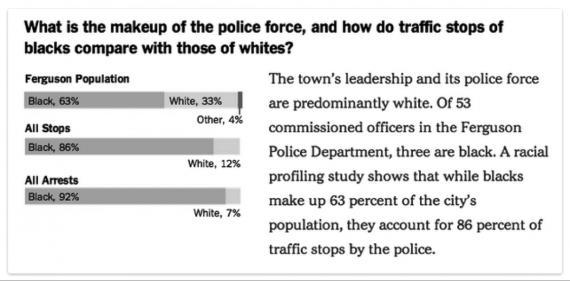

Still, the greater underlying grievance that seems to have inspired mass protest is the relationship between the police and the community. While the population of Ferguson is 63% Black, 90% of the police officers are White. As noted by the New York Times, in 2012, Blacks constituted 86% of all police stops and 92% of arrests. The Ferguson police responded to the protests after Brown’s death with strong militarized force. Images of officers in full military gear, driving armored vehicles, and sharpshooters with high caliber weaponry got the attention of the media. The images coming out of Ferguson looked more like U.S. military commandos at war in Iraq or Afghanistan than cops working in an American suburb.

Here again we see how the events in Ferguson illustrate larger social trends. The distribution of military weaponry to local police departments began after the terrorist attacks of September 11th, 2001 under the guise of community preparation. As legal scholar Michelle Alexander has pointed out, today we see the weaponry and tactics of the military used on civilians by paramilitary SWAT units in police departments across the country. In June 2014, the ACLU published a report documenting the increased use of SWAT raids for search warrants for low-level drug investigations. These tactics have resulted in the deaths of innocent people, including infants and children. Additionally, these tactics are used disproportionately in cases involving racial and ethnic minority suspects. Do they pay off? According to the ACLU’s research, the majority of the time, they do not. Drugs are only found in about a third of SWAT-like raids.

So, was the shooting in Ferguson an isolated event between two individuals, police officer Darren Wilson and Michael Brown? No. The impoverished community context had left community members feeling disconnected from the rewards of mainstream society. The stereotyping of Black males as “thugs” likely added to the officer’s fear of Michael, activating a socially constructed cognitive cue—“danger”—and a panicked fatal shooting. Further, the city’s history of racial profiling and an almost exclusively White police force contributed to community mistrust of police actions. Then, when protests arose, the police response grew out of the already-established militarization driven by the “war on terror” and the power of the military industrial complex in our economy (and foreign policy).

For instructors planning the nitty-gritty of sociology courses—the books to be used, the supplemental readings, the sequence of the topics, creative in-class activities and the types of assessment—is a challenge, and, many would agree, something of an art form. Instructors often agonize, rework, and consult colleagues in making these important decisions. However, the ever-changing world and our dynamic society also present instructors with opportunities to teach sociology “as it happens.” Tying course concepts to current events helps students understand explicitly how sociology is relevant to the present day and to their own lives.

An instructor who has polished his or her syllabus for the semester may be hesitant to alter it. But knowing that students can gain a greater understanding of the social world using sociological concepts and tools to analyze timely current events, how can instructors adapt their classes quickly to incorporate the moment? Given that Brown was killed just a couple of weeks before the start of the fall semester and the grand jury’s decision was released toward the semester’s end, teaching Ferguson is a representative example of the challenges of teaching current events.

The Internet is emerging as a better and better tool to help instructors become more agile on their pedagogical feet, so to speak. However, one of the challenges instructors face is how to decipher “good” credible information from the “fire hose” of information that makes up the web. When trying to teach the immediate, instructors need to be able to quickly distinguish credible information. Social media such as Twitter, Facebook, Google+, and Tumblr, as well as numerous sociology blogs (for example, sociologytoolbox.com and sociologysource.org) and shared file venues like GoogleDrive and DropBox generate new spaces to quickly accumulate tools and disseminate useful information. The events in Ferguson propelled the use of these “crowd-sourced” opportunities a significant step forward.

One of the most interesting tools to emerge was a Twitter hashtag: #FergusonSyllabus. On August 27th, just two weeks after the shooting, Dr. Marcia Chatelain, a history professor at Georgetown University, started tagging teaching materials like articles, assignments, and activities focused on Brown’s death and the social response with the #FergusonSyllabus so that interested teachers could find them quickly. That is all it took for the collective community to start contributing their own ideas and resources for teaching Ferguson under this and similar hashtags, including #TeachFerguson and #FergusonTeachIn.

Sociologists for Justice, a group that, on its website, describes itself as “an independent collective of sociologists troubled by the killing of Michael Brown and the excessive show of force and militarized response to protesters” narrowed this list down to 18 key, peer-reviewed articles and books focused on policing and the black community. Digging around on the Internet reveals even more resources: movies, discussion questions, and related pieces of literature. The organization of these efforts using #FergusonSyllabus narrowed the search down to a digestible level. A wider array of useful classroom resources are available on a publicly accessible GoogleDocs page. These file sharing sites have immense potential for crowdsourcing resources to help instructors quickly respond to external events.

When teaching headline-grabbing current events, instructors should not enter the classroom assuming students pay attention to the news at the same level they do. Part of any assigned reading may need to be a summary or key article to get all the students on the same page regarding the events. Resources like the timeline of events that the New York Times published regarding Michael Brown’s death serve as good summaries and jumping-off points.

In the days and weeks after such striking current events, instructors can also follow up in the classroom with opinion poll data from organizations like Pew, Roper, and Gallup. These organizations often make their data public and make some effort to stay relevant to current events. These sources can provide updated descriptive data. In the case of Ferguson, Gallup data showed the national racial divide over the confidence in police: Blacks had lower rates of confidence in the protective capacity of the police. Pew Research had interesting data, too, showing that Blacks indicated twice as often as Whites (80% vs. 37%) that the Ferguson case raised important issues about race. Numbers like these make clear the racial aspects of events like those in Ferguson.

Should classroom schedules and curriculum be controlled by the whims of the news cycle? No. Certainly instructors and students need some predictability in order to fully prepare. However, engaged instructors cannot ignore powerful opportunities to deepen the learning of students by remaining academically and pedagogically agile.