Explaining and Eliminating Racial Profiling

The emancipation of slaves is a century-and-a-half in America’s past. Many would consider it ancient history.

Even the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act, which challenged the de facto racial apartheid of the post-Civil War period, are now well over 40 years old.

But even in the face of such well-established laws, racial inequalities in education, housing, employment, and law enforcement remain widespread in the United States.

Many Americans think these racial patterns stem primarily from individual prejudices or even racist attitudes. However, sociological research shows discrimination is more often the result of organizational practices that have unintentional racial effects or are based on cognitive biases linked to social stereotypes.

Racial profiling—stopping or searching cars and drivers based primarily on race, rather than any suspicion or observed violation of the law—is particularly problematic because it’s a form of discrimination enacted and organized by federal and local governments.

In our research we’ve found that sometimes formal, institutionalized rules within law enforcement agencies encourage racial profiling. Routine patrol patterns and responses to calls for service, too, can produce racially biased policing. And, unconscious biases among individual police officers can encourage them to perceive some drivers as more threatening than others (of course, overt racism, although not widespread, among some police officers also contributes to racial profiling).

Racially biased policing is particularly troubling for police-community relations, as it unintentionally contributes to the mistrust of police in minority neighborhoods. But, the same politics and organizational practices that produce racial profiling can be the tools communities use to confront and eliminate it.

Profiling and its Problems

The modern story of racially biased policing begins with the Drug Enforcement Agency’s (DEA) Operation Pipeline, which starting in 1984 trained 25,000 state and local police officers in 48 states to recognize, stop, and search potential drug couriers. Part of that training included considering the suspects’ race.

Jurisdictions developed a variety of profiles in response to Operation Pipeline. For example, in Eagle County, Colo., the sheriff’s office profiled drug couriers as those who had fast-food wrappers strewn in their cars, out-of-state license plates, and dark skin, according to the book Good Cop, Bad Cop by Milton Heuman and Lance Cassak. As well, those authors wrote, Delaware’s drug courier profile commonly targeted young minority men carrying pagers or wearing gold jewelry. And according to the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), the Florida Highway Patrol’s profile included rental cars, scrupulous obedience to traffic laws, drivers wearing lots of gold or who don’t “fit” the vehicle, and ethnic groups associated with the drug trade (meaning African Americans and Latinos).

In the 1990s, civil rights organizations challenged the use of racial profiles during routine traffic stops, calling them a form of discrimination. In response, the U.S. Department of Justice argued that using race as an explicit profile produced more efficient crime control than random stops. Over the past decade, however, basic social science research has called this claim into question.

The key indicator of efficiency in police searches is the percent that result in the discovery of something illegal. Recent research has shown repeatedly that increasing the number of stops and searches among minorities doesn’t lead to more drug seizures than are found in routine traffic stops and searches among white drivers. In fact, the rates of contraband found in profiling-based drug searches of minorities are typically lower, suggesting racial profiling decreases police efficiency.

In addition to it being an inefficient police practice, Operation Pipeline violated the assumption of equal protection under the law guaranteed through civil rights laws as well as the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. It meant, in other words, that just as police forces across the country were learning to curb the egregious civil rights violations of the 20th century, the federal government began training state and local police to target black and brown drivers for minor traffic violations in hopes of finding more severe criminal offending. The cruel irony is that it was exactly this type of flagrant, state-sanctioned racism the civil rights movement was so successful at outlawing barely a decade earlier.

Following notorious cases of violence against minorities perpetrated by police officers, such as the video-taped beating of Rodney King in Los Angeles in 1991 and the shooting of Amadou Diallo in New York in 1999, racially biased policing rose quickly on the national civil rights agenda. By the late 1990s, challenges to racial profiling became a key political goal in the more general movement for racial justice.

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the ACLU brought lawsuits against law enforcement agencies across the United States for targeting minority drivers. As a result, many states passed legislation that banned the use of racial profiles and then required officers to record the race of drivers stopped in order to monitor and sanction those who were violating citizens’ civil rights.

Today, many jurisdictions continue to collect information on the race composition of vehicle stops and searches to monitor and discourage racially biased policing. In places like New Jersey and North Carolina, where the national politics challenging racial profiling were reinforced by local efforts to monitor and sanction police, racial disparities in highway patrol stops and searches declined.

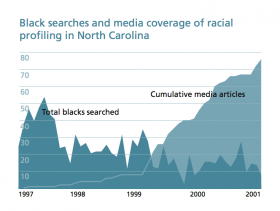

Our analysis of searches by the North Carolina Highway Patrol shows that these civil rights-based challenges, both national and local, quickly changed police behavior. In 1997, before racial profiling had come under attack, black drivers were four times as likely as white drivers to be subjected to a search by the North Carolina Highway Patrol. Confirming that the high rate of searches represented racial profiling, black drivers were 33 percent less likely to be found with contraband compared to white drivers. The next year, as the national and local politics of racial profiling accelerated, searches of black drivers plummeted in North Carolina. By 2000, racial disparities in searches had been cut in half and the recovery of contraband no longer differed by race, suggesting officers were no longer racially biased in their decisions to search cars.

Our analysis of searches by the North Carolina Highway Patrol shows that these civil rights-based challenges, both national and local, quickly changed police behavior. In 1997, before racial profiling had come under attack, black drivers were four times as likely as white drivers to be subjected to a search by the North Carolina Highway Patrol. Confirming that the high rate of searches represented racial profiling, black drivers were 33 percent less likely to be found with contraband compared to white drivers. The next year, as the national and local politics of racial profiling accelerated, searches of black drivers plummeted in North Carolina. By 2000, racial disparities in searches had been cut in half and the recovery of contraband no longer differed by race, suggesting officers were no longer racially biased in their decisions to search cars.

This isn’t to suggest lawyers’ and activists’ complaints have stopped profiling everywhere. For example, Missouri, which has been collecting data since 2000, still has large race disparities in searching practices among its police officers. The most recent data (for 2007) shows blacks were 78 percent more likely than whites to be searched. Hispanics were 118 percent more likely than whites to be searched. Compared to searches of white drivers, contraband was found 25 percent less often among black drivers and 38 percent less often among Hispanic drivers.

How Bias is Produced

Many police-citizen encounters aren’t discretionary, therefore even if an officer harbors racial prejudice it won’t influence the decision to stop a car. For example, highway patrol officers, concerned with traffic flow and public safety, spend a good deal of their time stopping speeders based on radar readings—they often don’t even know the race of the driver until after they pull over the car. Still, a number of other factors can produce high rates of racially biased stops. The first has to do with police patrol patterns, which tend to vary widely by neighborhood.

Not unreasonably, communities suffering from higher rates of crime are often patrolled more aggressively than others. Because minorities more often live in these neighborhoods, the routine deployment of police in an effort to increase public safety will produce more police-citizen contacts and thus a higher rate of stops in those neighborhoods.

A recent study in Charlotte, N.C., confirmed that much of the race disparity in vehicle stops there can be explained in terms of patrol patterns and calls for service. Another recent study of pedestrian stops in New York yielded similar conclusions—but further estimated that police patrol patterns alone lead to African American pedestrians being stopped at three times the rate of whites. (And, similar to the study of racial profiling of North Carolina motorists, contraband was recovered from white New Yorkers at twice the rate of African Americans.)

Police patrol patterns are, in fact, sometimes more obviously racially motivated. Targeting black bars, rather than white country clubs, for Saturday-night random alcohol checks has this character. This also happens when police stop minority drivers for being in white neighborhoods. This “out-of-place policing” is often a routine police practice, but can also arise from calls for service from white households suspicious of minorities in their otherwise segregated neighborhoods. In our conversations with African American drivers, many were quite conscious of the risk they took when walking or driving in white neighborhoods.

Police patrol patterns are, in fact, sometimes more obviously racially motivated. Targeting black bars, rather than white country clubs, for Saturday-night random alcohol checks has this character. This also happens when police stop minority drivers for being in white neighborhoods. This “out-of-place policing” is often a routine police practice, but can also arise from calls for service from white households suspicious of minorities in their otherwise segregated neighborhoods. In our conversations with African American drivers, many were quite conscious of the risk they took when walking or driving in white neighborhoods.

“My son…was working at the country club… He missed the bus and he said he was walking out Queens Road. After a while all the lights came popping on in every house. He guessed they called and … the police came and they questioned him, they wanted to know why was he walking through Queens Road [at] that time of day,” one black respondent we talked to said.

The “wars” on drugs and crime of the 1980s and 1990s encouraged law enforcement to police minority neighborhoods aggressively and thus contributed significantly to these problematic patterns. In focus groups with African American drivers in North Carolina, we heard that many were well aware of these patterns and their sources. “I think sometimes they target … depending on where you live. I think if you live in a side of town … with maybe a lot of crime or maybe break-ins or drugs, … I think you are a target there,” one respondent noted.

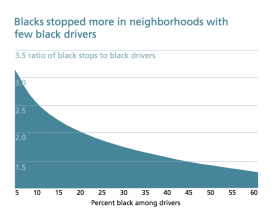

These stories are mirrored in data on police stops in a mid-size midwestern city reported in the figure above, right. Here, the fewer minorities there are in a neighborhood, the more often African Americans are stopped. In the whitest neighborhoods, African American drivers were stopped at three times the rate you’d expect given how many of them are on the road. In minority communities, minority drivers were still stopped disproportionally, but at rates much closer to their population as drivers in the neighborhood.

This isn’t to say all racial inequities in policing originate with the rules organizations follow. Racial attitudes and biases among police officers are still a source of racial disparity in police vehicle stops. But even this is a more complicated story than personal prejudice and old-fashioned bigotry.

Bias Among Individual Officers

The two most common sources of individual bias are conscious prejudice and unconscious cognitive bias. Conscious prejudice is typically, but incorrectly, thought of as the most common source of individuals’ racist behavior. While some individual police officers, just like some employers or real estate agents, may be old-fashioned bigots, this isn’t a widespread source of racial bias in police stops. Not only is prejudice against African Americans on the decline in the United States, but most police forces prohibit this kind of racism and reprimand or punish such officers when it’s discovered. In these cases, in fact, organizational mechanisms prevent, or at least reduce, bigoted behavior.

Most social psychologists agree, however, that implicit biases against minorities are widespread in the population. While only about 10 percent of the white population will admit they have explicitly racist attitudes, more than three-quarters display implicit anti-black bias.

Studies of social cognition (or, how people think) show that people simplify and manage information by organizing it into social categories. By focusing on obvious status characteristics such as sex, race, or age, all of us tend to categorize ourselves and others into groups. Once people are racially categorized, stereotypes automatically, and often unconsciously, become activated and influence behavior. Given pervasive media images of African American men as dangerous and threatening, it shouldn’t be surprising that when officers make decisions about whom to pull over or whom to search, unconscious bias may encourage them to focus more often on minorities.

These kinds of biases come into play especially for local police who, in contrast to highway patrol officers, do much more low-speed, routine patrolling of neighborhoods and business districts and thus have more discretion in making decisions about whom to stop.

In our research in North Carolina, for example, we found that while highway patrol officers weren’t more likely to stop African American drivers than white drivers, local police stopped African Americans 70 percent more often than white drivers, even after statistically adjusting for driving behavior. Local officers were also more likely to stop men, younger drivers, and drivers in older cars, confirming this process was largely about unconscious bias rather than explicit racial profiles. Race, gender, age, class biases, and stereotypes about perceived dangerousness seem to explain this pattern of local police vehicle stops.

Strategies for Change

Unconscious biases are particularly difficult for an organization to address because offending individuals are typically unaware of them, and when confronted they may deny any racist intent.

There is increasing evidence that even deep-seated stereotypes and unconscious biases can be eroded through both education and exposure to minorities who don’t fit common stereotypes, and that they can be contained when people are held accountable for their decisions. Indeed, it appears that acts of racial discrimination (as opposed to just prejudicial attitudes or beliefs) can be stopped through managerial authority, and prejudice itself seems to be reduced through both education and exposure to minorities.

For example, a 2006 study by sociologists Alexandra Kalev, Frank Dobbin, and Erin Kelly of race and gender employment bias in the private sector found that holding management accountable for equal employment opportunities is particularly efficient for reducing race and gender biases. Thus, the active monitoring and managing of police officers based on racial composition of their stops and searches holds much promise for mitigating this “invisible” prejudice.

Citizen and police review boards can play proactive and reactive roles in monitoring both individual police behavior as well as problematic organizational practices. Local police forces can use data they collect on racial disparity in police stops to identify problematic organizational behaviors such as intensively policing minority neighborhoods, targeting minorities in white neighborhoods, and racial profiling in searches.

Aggressive enforcement of civil rights laws will also play a key role in encouraging local police chiefs and employers to continue to monitor and address prejudice and discrimination inside their organizations. This is an area where the federal government has a clear role to play. Filing lawsuits against cities and states with persistent patterns of racially biased policing—whether based on the defense of segregated white neighborhoods or the routine patrolling of crime “hot spots”—would send a message to all police forces that the routine harassment of minority citizens is unacceptable in the United States.

Justice in the Obama Era

Given the crucial role the federal justice department has played in both creating and confronting racial profiling, one may wonder whether the election of President Barack Obama will have any consequences for racially biased policing.

Obama certainly has personal reasons to challenge racist practices. And given the success of his presidential campaign, it would seem he has the political capital to address racial issues in a way and to an extent unlike any of his predecessors.

At the same time, the new president has vowed to continue to fight a war on terrorism, a war often understood and explicitly defined in religious and ethnic terms. In some ways, the threat of terrorism has replaced the threat of African Americans in the U.S. political lexicon. There’s evidence as well that politicians, both Democrat and Republican, have increased their verbal attacks on illegal immigrants and in doing so may be providing a fertile ground for new rounds of profiling against Hispanics in this country. So, while the racial profiling of African Americans as explicit national policy is unlikely in the Obama Administration, other groups may not be so lucky.

Americans committed to racial justice and equality will likely take this as a cautionary tale. They will also likely hope the Obama Administration decides to take a national leadership role in ending racial profiling. But if it does, as sociologists we hope the administration won’t make the all too common mistake of assuming racial profiling is primarily the result of racial prejudice or even the more widespread psychology of unconscious bias.

Recommended Resources

American Civil Liberties Union. “The Racial Justice Program.” The leading civil rights agency speaking out against racial profiling has actively challenged police departments across the United States on biased policing practices.

N. Dasgupta and Anthony Greenwald. 2001. “On the malleability of automatic attitudes: Combating automatic prejudice with images of admired and disliked individuals,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology (2001) 81: 800–814. Shows unconscious cognitive biases can be countered by positive, stereotype-disrupting role models.

Alexandra Kalev, Frank Dobbin, and Erin Kelly. 2006. “Best practices or best guesses? Assessing the efficacy of corporate affirmative action and diversity polices,” American Sociological Review (2006) 71: 598–617. Shows that holding managers accountable for racial and gender bias leads to lower levels of discrimination.

Racial Profiling Data Collection Resource Center. “Legislation and Litigation.” Provides detailed information about racial profiling studies across the United States.

Patricia Warren, Donald Tomaskovic-Devey, William Smith, Matthew Zingraff, and Marcinda Mason. “Driving While Black: Bias Processes and Racial Disparity in Police Stops,” Criminology (2006) 44: 709–738. Uses survey data to identify the mechanisms that give rise to racial disparity in traffic stops.

online resources

To learn more about state-by-state legislation against racial profiling, visit the Racial Profiling Data Collection Resource Center. Currently, 19 states have not taken any action to pass anti-profiling legislation and 5 states have legislation pending. Find out if your state is among these, and then contact your representatives to help get legislation passed.

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) has been and continues to be active in the struggle against racial profiling. Watch this video about a 1997 ACLU law suit on behalf of 12 drivers who experienced racial profiling:

Check out the Missouri Attorney General’s annual Racial Profiling Reports. The reports include statewide data on stops, searches, contraband hit rates, and arrest rates broken down for whites, blacks, Hispanics, Asians, American Indian, and other racial groups. In 2007, for example, blacks were 58% more likely to be stopped in Missouri than would be expected given their proportion of the population.

The Impact Fund is bringing a lawsuit against Antioch, a city near San Francisco, claiming the City and its Police Department harass African American Section 8 tenants because of their race. The lawsuit alleges unlawful searches of homes, “heavy-handed” police investigations, actions to negatively influence landlords, and solicitation of complaints from neighbors. This San Francisco Chronicle article covers the story.

Finally, a video of the 1991 Rodney King beating, referenced in the article, provides a widely-publicized example of excessive use of police force:

Comments 4

Verlinkenswertes (KW 21/09) | Criminologia

May 24, 2009[...] Explaining and Eliminating Racial Profiling (Contexts Magazine, 21.05.2009) [...]

City of Antioch ACLU Lawsuit Still in Discovery Phase | Antioch Grove

September 2, 2009[...] “The key indicator of efficiency in police searches is the percent that result in the discovery of something illegal. Recent research has shown repeatedly that increasing the number of stops and searches among minorities doesn’t lead to more drug seizures than are found in routine traffic stops and searches among white drivers. In fact, the rates of contraband found in profiling-based drug searches of minorities are typically lower, suggesting racial profiling decreases police efficiency.” (Donald Tomaskovic-Devey and Patricia Warren ) [...]

City of Antioch ACLU Lawsuit Still in Discovery Phase | Brentwood Grove

January 23, 2010[...] “The key indicator of efficiency in police searches is the percent that result in the discovery of something illegal. Recent research has shown repeatedly that increasing the number of stops and searches among minorities doesn’t lead to more drug seizures than are found in routine traffic stops and searches among white drivers. In fact, the rates of contraband found in profiling-based drug searches of minorities are typically lower, suggesting racial profiling decreases police efficiency.” (Donald Tomaskovic-Devey and Patricia Warren ) [...]

BOI123

September 6, 2013YO HOW DID RACIAL PROFILING PROGRESS OVER DA YEARS U FEEL ME IM TRYNA GET AN ANSWER