Aging Women, Living Poorer

This year 37 million retired workers received a 1.5 percent increase in their monthly Social Security checks—one of the lowest raises since cost-of-living adjustments began in 1975. While this modest boost is an improvement over recent years (when raises stalled due to negative or scant inflation), daily living expenses and rising out-of-pocket health care costs will quickly eat up the average $19 increase for seniors on fixed incomes.

Due to the graying of the population, more people than ever rely on Social Security to meet basic needs. According to the most recent Census, people over age 65 comprise 13.7 percent of the total U.S. population today—more than during any previous year. But this number, which will increase with the aging of baby boomers, tells only part of the story. The majority of older Americans are women. Women live longer than men, and elderly women 65 years and older outnumber elderly men by three to two, making aging in late life a women’s issue. This means that any changes to existing policies that affect the old, like Social Security and Medicare, will primarily affect old women. Yet such gendered realities are often lost in media coverage and ongoing public discussions of Social Security reform.

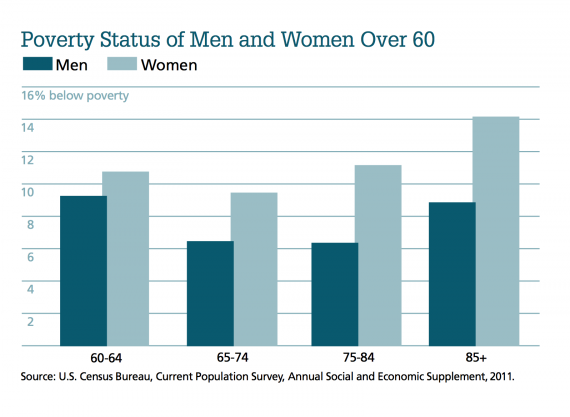

While overall poverty rates for the elderly have declined from 35 percent in 1959 to 8.7 percent in 2011, gender differences in late-life poverty persist. In 2011, the poverty rate for women over 65 reached 10.7 percent, compared to 6.2 percent for men. My analysis of poverty data from the Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey (Annual and Economic Supplement, 2003-2011) reveals important gender differences in older women’s and men’s poverty rates across the following age groups: 60-64 years, 65-74 years, 75-84 years, and 85+ years. It suggests that women continue to face significant economic disadvantages in old age, and that the proportion of older women in poverty increases as women age.

In the United States, 65 is an important age benchmark tied to the distribution of Social Security benefits and eligibility for “full retirement.” But economic vulnerability varies for men and women in later life. Key transitions in old age, such as when one becomes eligible for full retirement benefits, may alleviate poverty; other changes, such as shifts in living arrangements and marital status, may increase an individual’s susceptibility to poverty.

According to the Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey (CPS), men have lower poverty rates than women across all 60+ age groups; they also experience less fluctuation in these rates as they age. The percentage of men living below the official poverty line was higher for men aged 60-64 than those aged 65-74 from 2002 to 2010 (the most recent year for which CPS data were available at the time of this writing). For example, in the chart below, in 2010, 9.3 percent of men aged 60-64 fell below the poverty line, compared with 6.5 percent of men aged 65-74. This pattern of lower poverty rates for older men (an average 2 percent lower across a nine-year period) suggests that the benefit of reaching full retirement age helps lift some older men out of the ranks of the desperately poor. Comparing the percentage of poor men aged 65-74 with those aged 75-84 revealed no significant differences. Among those over 65, men aged 85 and older had the highest poverty rates. But the percentage of “oldest old” men who were below the poverty line still remained lower than the poverty rate among men aged 60-64, suggesting that men have a more consistent and more substantial economic cushion as they age.

Women’s economic prospects past age 65 are much less secure. Looking at differences in poverty rates for women across different age groups, we see that, among adults 60 and older, women had higher poverty rates than their male counterparts in every age group. Much like men, fewer women aged 65-74 were poor, compared to those aged 60-64, suggesting that are some immediate economic benefits for women who reach full retirement age. But the average difference in poverty rates between women in these two age groups was more modest than men’s differences (0.4 percent versus 2 percent) and did not decrease every year. Women faced steady increases in poverty rates as they aged.

Poverty rates in 2010 for women aged 65-74 stood at 9.5 percent, rose to 11.2 percent for women aged 75-84, and increased again to 14.2 percent among women 85 and older. In contrast to men’s late life poverty, the average percentage of women below poverty in the 85+ age group was nearly 5 percent higher than the percentage of women in poverty for the 60-64 age group (in all years from 2002-2010).

Why does poverty persist for women, and which women are hit hardest as they age? For many, a lifetime of unpaid, work-interrupting caregiving responsibilities is one cause. Divorce, labor market discrimination, and inequalities built into Social Security and employer pension programs are also frequent factors which leave women worse off as they enter old age. Women continue to face problems under the Social Security system due to gendered wage gaps and their more erratic work histories (exiting and reentering the labor force more frequently than men due to unpaid caregiving). These interruptions limit both take-home pay and lifetime Social Security benefits. Taking years “off” incurs a motherhood penalty, and a “zero year” is entered into a worker’s record for each year the worker did not perform paid labor. Though the Social Security Administration bases retirement benefits on the highest 35 years of earnings, older women average 11.5 years out of the work force, compared with men who average only a year away. That’s a lot of zeros averaged into women’s retirement benefits. When women who worked outside the home collect Social Security and pensions based on their earnings, their payouts tend to be substantially lower.

Because women live longer, they also face the challenge of having more expensive health problems in the face of dwindling resources. Older women are more likely to live alone (36 percent of women over 65, versus 19 percent of men). This rate increases with age, and almost half of women age 75 and older live alone. Women who remain single and live alone suffer the most economically. Poverty among older women living alone increased to 18.4 percent in 2011, up from 17 percent the previous year, though it’s too early to tell whether this uptick represents an emerging trend. However, it’s little surprise that women’s poverty rates spike upon widowhood. Because they live longer, and tend to marry men older than themselves, they are nearly three times more likely than elderly men to be widowed. These women are more likely to remain single than widowed men, who have a higher likelihood of remarriage. Seventy-two percent of men 65 and older were married in 2012, compared to 45 percent of women over 65.

What might the future of women’s aging look like? Baby boomers’ desire to “age in place” and live in their own homes independently for as long as possible, coupled with higher rates of divorce and lifelong singlehood, will further the trend of solo living among new generations of older women. While declining elder poverty has enabled greater rates of independent living, this independence depends on government programs like Social Security and support services such as senior centers, in-home meal delivery, and home health aides. Cuts to these and other programs threaten the ability of older people, particularly women who suffer higher poverty rates in old age, to thrive on their own.

Eliminating the motherhood penalty built into the current Social Security system, and providing caregiver credits that reduce the number of zero years that are factored into benefit calculations, would go a long way towards safeguarding a more secure retirement for future generations of women. Sociologist Pamela Herd, writing in Social Forces in 2005, showed that implementing a minimum benefit, as opposed to the current model of earnings-based benefits, would go even further in helping reduce class inequality among different groups of women and protecting the poorest women, especially single parents. As we develop policies to help meet the needs of our aging population, we need strategies that will support all women.