Breastfeed At Your Own Risk

For nearly two years, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services spent $2 million on an ad campaign to promote breastfeeding by educating mothers about the risks of not doing so.

Those risks were often communicated in provocative ways. One television ad, for example, showed a pregnant African American woman riding a mechanical bull, and then the message appears on the screen, “You wouldn’t take risks before your baby is born. Why start after?”

This campaign was the culmination of three decades of increasing consensus among medical and public health professionals that, as the saying goes, “breast is best”—that there is no better nutrition for the first year of an infant’s life than breastmilk. The endorsement of the medical establishment is echoed in advice books and parenting magazines that overwhelmingly recommend breastfeeding over formula. Communities have passed laws to support breastfeeding mothers in the workplace and to ensure public breastfeeding isn’t legally categorized as indecency.

And rates of breastfeeding in the United States have increased dramatically—nearly 75 percent of mothers now breastfeed newborns, up from 24 percent in 1971. Rates of breastfeeding are even higher among middle-class, educated mothers. For these mothers, breastfeeding has become less of a choice and more of an imperative—a way to protect their infant’s health and boost their IQ. Breastfeeding is a way to achieve so-called good mothering, the idealized notion of mothers as selfless and child-centered.

Taking a sociological look at the cultural imperative to breastfeed illustrates how mothering is shaped by discussions among scientists, doctors, and other experts, as well as policy recommendations that grow out of scientific findings. It also reveals that breastfeeding and infant feeding practices differ by culture, race, class, and ethnicity, and that the “breast is best” conventional wisdom doesn’t take these differences into account. Thus, this campaign leaves many mothers feeling inadequate—and perhaps unnecessarily so because the scientific evidence about the benefits of breastfeeding are less clear-cut than mothers have been led to believe.

Historical Trends in Breastfeeding

Cultural ideas about motherhood and family in the United States have changed significantly over time, thanks in part to science and technology.

Religious authorities, midwives, and physicians encouraged mothers in the 17th and 18th centuries to breastfeed their infants. The practice through the mid-1800s, in a primarily farm-based society, was to nurse infants through their “second summer” to avoid unrefrigerated and possibly spoiled food and milk.

Wet nursing—breastfeeding a child who is not a woman’s own—became necessary when a mother was severely ill or died during childbirth. Breastmilk was widely thought superior to “hand-feeding”—providing milk, tea, or “pap” (a mixture of flour, sugar, water, and milk)—in promoting infant health, but even so, according to historian Janet Golden in her study A Social History of Wet Nursing, families worried about having a wet nurse of “questionable” moral fitness, and these fears were exacerbated by race and class divisions. In the north, wet nurses were typically poor immigrant mothers; in the south, they tended to be African Americans, and it was common for female slaves to be wet nurses in the antebellum south. However, by the turn of the 20th century, the use of wet nurses had declined, in part because pasteurization made bottle-feeding a safe alternative to breastmilk. This was also the era in which children came to be seen as priceless, in need of protection, and worth extraordinary investment, sociologist Viviana Zelizer explained in Pricing the Priceless Child.

Wet nursing—breastfeeding a child who is not a woman’s own—became necessary when a mother was severely ill or died during childbirth. Breastmilk was widely thought superior to “hand-feeding”—providing milk, tea, or “pap” (a mixture of flour, sugar, water, and milk)—in promoting infant health, but even so, according to historian Janet Golden in her study A Social History of Wet Nursing, families worried about having a wet nurse of “questionable” moral fitness, and these fears were exacerbated by race and class divisions. In the north, wet nurses were typically poor immigrant mothers; in the south, they tended to be African Americans, and it was common for female slaves to be wet nurses in the antebellum south. However, by the turn of the 20th century, the use of wet nurses had declined, in part because pasteurization made bottle-feeding a safe alternative to breastmilk. This was also the era in which children came to be seen as priceless, in need of protection, and worth extraordinary investment, sociologist Viviana Zelizer explained in Pricing the Priceless Child.

Technological advancements led to the development of mass-marketed infant formula in the 1950s. Doctors then began to recommend formula, saying a scientifically developed substance was at least equivalent to, and possibly better than, breastmilk. By the early 1970s, breastfeeding rates in hospitals were at a low of approximately 24 percent, with only 5 percent of mothers nursing for several months following birth.

It was in this era that some feminist women’s health groups and Christian women’s groups such as La Leche League began challenging the medical model by promoting “natural” childbirth and breastfeeding. These groups promoted the benefits of breastfeeding and also raised public awareness about the activities of formula companies.

For example, some feminist health groups helped organize a boycott of Nestle in the late 1970s for promoting formula in developing countries. These groups claimed that Nestle’s formula marketing tactics in Africa had led to 1 million infant deaths (from mixing powered formula with contaminated water, or feeding infants diluted formula because of the expense). The success of these small groups in challenging the corporate marketing of formula led to increasing consensus that breastfeeding was better than bottlefeeding. Soon, the medical establishment was embracing breastfeeding, based on scientific studies that confirmed the benefits La Leche League and other feminist health groups had been talking about for years. In 1978, the American Academy of Pediatricians (AAP) recommended breastfeeding over formula, marking the beginning of the shift in mainstream medical advice to mothers. Since then, scientific evidence and the medical establishment have continued to reaffirm the benefits of breastmilk.

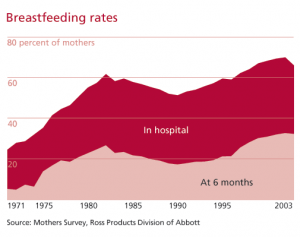

Trends over the last 40 years gathered from a survey of mothers show how experts’ recommendations and public discussions about breastfeeding have influenced breastfeeding rates. The graph above shows the sharp increase in breast feeding in the 1970s. In the 1980s, there is a slight decrease and plateau in breastfeeding initiation rates, and then, in the 1990s, the rate steadily rises to nearly 70 percent. The rates of breastfeeding until six months of age follow a very similar pattern, although overall the rates are quite lower than breastfeeding initiation; currently, only about one-third of mothers report breastfeeding at six months. This recent rise in breastfeeding rates can be explained, at least in part, by the ideology of intensive mothering.

Breastfeeding as Intensive Mothering

Childrearing advice books, pediatricians, parenting magazines, and even formula companies themselves now universally recommend breastmilk over formula. The consensus that “breast is best” is embedded in cultural ideals of motherhood.

In her book The Cultural Contradictions of Motherhood, sociologist Sharon Hays identifies an ideology of intensive mothering and describes how it’s at work in the United States: Mothers—not fathers—serve as the primary caregivers of children; mothering practices are time-intensive, expensive, supported by expert advice, child-centered, and emotionally absorbing; and children are viewed as priceless, and the work that must be done to raise them can’t be compared to paid work because it’s infinitely more important.

The ideology of intensive mothering helps explain why we hear so much playground chatter and read so many magazine articles about getting children into the “best” school, the idea that natural childbirth is better than one assisted by medication or other medical interventions, and the recent discussion of “opt-out” mothers who leave high-powered jobs to stay home with their children. Hays contends the strength of the intensive mothering ideology is the result of an “ambivalence about a society based solely on the competitive pursuit of self-interest.”

This may be one reason, for example, journalist Judith Warner, in her book Perfect Madness: Motherhood in the Age of Anxiety, felt such a difference when she was mothering in France compared to when she returned with her children to the United States. In France the state offers practical support to mothers, including subsidized childcare, universal healthcare, and excellent public education beginning at age 3. Furthermore, Warner explained that, as a new mother there, she found herself in the middle of an extensive and sympathetic support network that attended to her needs as a mother as much as they attended to the needs of her child. “It was a bad thing [for mothers] to go it alone,” she wrote. In contrast, upon her return to the United States Warner felt isolated and anxious. She linked this directly to what she called the “American culture of rugged individualism.” Mothers in the United States were under extraordinary pressure to be a “good mother”—otherwise, who else would protect their child from an individualistic, self-interested society?

The cultural imperative to breastfeed is part of the ideology of intensive mothering—it requires the mother be the central caregiver, because only she produces milk; breastfeeding is in line with expert advice and takes a great deal of time and commitment; and finally, the act of breastfeeding is a way to demonstrate that the child is priceless, and that whatever the cost, be it a loss of productivity at work or staying at home, children come first.

Since Hays links the intensive motherhood ideology to American individualistic sensibilities, it would seem to suggest that breastfeeding rates in the United States would be higher than other countries. To return to the example of France, only 50 percent of French mothers breastfeed their newborns, compared to 75 percent of American mothers. However, upon closer examination of statistics compiled by Le Leche League International, U.S. breastfeeding rates lag far behind many other countries, including European countries other than France (Germany, Italy, Spain, and the Scandinavian countries all have breastfeeding initiation rates around 90 percent). Most countries in Asia, Africa, and South America report breastfeeding initiation rates higher than the United States, as do New Zealand and Australia.

Clearly the cultural imperative to breastfeed in the United States has met some resistance. This resistance may be reflected in public debates about breastfeeding, which quickly dissolve into mud-slinging, judgmental arguments that pit mothers against mothers. Not “the mommy wars” in the traditional sense—working moms versus stay-at-home moms—but instead bottlefeeding versus breastfeeding moms.

Breastfeeding mothers, and a subset of those mothers who are deeply committed to breastfeeding promotion (sometimes referred to as “lactivists”), point to a continuing undercurrent of resistance to breastfeeding. Despite the fact that scientists and doctors recommend breastfeeding, and that these recommendations have been disseminated through a public health ad campaign and parenting magazines, breastfeeding remains controversial. While society wants mothers to breastfeed to protect and promote infant health, it wants them to do so behind closed doors. Indeed mothers are often asked to cover themselves while nursing in restaurants.

For example, in 2007 a nursing mother was asked by an Applebee’s employee to cover herself while nursing or leave the restaurant. After repeated calls by enraged nursing mothers to the corporate headquarters, executives there insisted it was reasonable to ask the nursing mother to leave, despite a state law that extended mothers the right to nurse in public spaces. This incident resulted in “nurse-ins” at Applebee’s locations all over the United States in protest. The social networking site Facebook found itself in a similar firestorm of controversy at the beginning of 2009 when it removed photos of breastfeeding mothers because they violated the site’s decency standards. The resistance to nursing-in-public arises from the link between breasts and sexuality, including the idea that breasts are indecent.

Note that these public debates about breastfeeding and mothering in the United States emerge primarily from discussions by and about middle class mothers. The ideal of intensive mothering is much easier for these women to achieve. Even so, studies have explored the extensive labor middle class mothers must engage in just to meet current breastfeeding recommendations.

Sociologist Orit Avishai demonstrates through interviews of white, middle class mothers that they treat breastfeeding not as a natural, pleasurable, connective act with their infant but instead as a disembodied project to be researched and managed. They take classes about breastfeeding, have home visits from lactation consultants post-partum, and view their bodies as feeding machines. When returning to work, they set up elaborate systems to pump breastmilk and store it. These middle-class women were accustomed to setting goals and achieving them—so when they decided to breastfeed for the one year the AAP recommends, they set out to do just that despite the physical and mental drawbacks. Although it’s easier for middle class mothers to meet the recommended breastfeeding standards than it is for less privileged mothers, they’re at the same time controlled by a culture that equates good mothering with breastfeeding.

Variations in Class and Culture

In At the Breast, sociologist Linda Blum examined how mothers of different classes aspired to or rejected the intensive mothering ideology and mainstream cultural imperative to breastfeed. Through interviews with white middle-class mothers who were members of La Leche League, as well as with a sample of both white and black working-class mothers, Blum’s study was the first (and is also the most extensive) to expose how the meaning of breastfeeding varies by class and race.

Her interviews with the La Leche mothers revealed the organization’s emphasis on an intimate, relational bond between mother and child created through breastfeeding. They rejected medical, scheduled, and mechanized infant feeding and emphasized how important it is for mothers to read their babies’ cues and be near them all the time. As such, a mother’s care is seen as irreplaceable. One mother told Blum, “Only a mother can give what a child needs, nobody else can, not even a father. A father can give almost as close, but only a mother can give what they really need.” Some of these mothers were also very critical of working mothers. “I’m pretty negative to people who just want to dump their kids off and go to work eight hours a day,” one said. Ultimately, Blum contends La Leche League is a self-help group largely created by and for white, middle-class women.

Her interviews with the La Leche mothers revealed the organization’s emphasis on an intimate, relational bond between mother and child created through breastfeeding. They rejected medical, scheduled, and mechanized infant feeding and emphasized how important it is for mothers to read their babies’ cues and be near them all the time. As such, a mother’s care is seen as irreplaceable. One mother told Blum, “Only a mother can give what a child needs, nobody else can, not even a father. A father can give almost as close, but only a mother can give what they really need.” Some of these mothers were also very critical of working mothers. “I’m pretty negative to people who just want to dump their kids off and go to work eight hours a day,” one said. Ultimately, Blum contends La Leche League is a self-help group largely created by and for white, middle-class women.

In contrast, interviews with white working-class mothers revealed they understood the health benefits of breastfeeding and embraced the ideal of intensive mothering, but that they often didn’t breastfeed because of constraints with jobs, lack of social support, inadequate nutrition, and limited access to medical advice. Working-class mothers were less likely to have jobs that allowed time and privacy to pump breastmilk and were less likely to have access to (paid or unpaid) maternity leave. Some felt it was embarrassing or restrictive. Yet, they still aspired to the middle class ideal of intensive mothering, so they were left feeling guilty and inadequate. Many reported feeling like their bodies had failed them. One mother, for example, said, “At first [breastfeeding] was great. I can’t explain the feeling, but at first it was really great. [But then,] I felt … useless, if I couldn’t nurse my baby, I was a flop as a mother.”

Ethnic and racial differences were even more unique and revealing. Black working-class mothers in Blum’s study were similar to white working-class mothers in understanding the health benefits of breastmilk. However, their discussions about not breastfeeding were, for the most part, remarkably free of guilt. In short, black mothers rejected the dominant cultural ideal of intensive mothering, and had a more broadly construed definition of what it meant to be a good mother. Many African American women, for example, talked about the importance of involving older children and extended family in caring for the child, and insisted one way this could be accomplished was through bottlefeeding. Some black mothers reacted negatively to breastfeeding because they believed it reinforced long-standing racist stereotypes about the black female body as threatening or even animalistic. By rejecting medical advice about breastfeeding, black mothers asserted some control over their own bodies. “The doctors said that breastmilk was the best, but I told them I didn’t want to. They tried to talk me into it, but they couldn’t,” one interviewee told Blum.

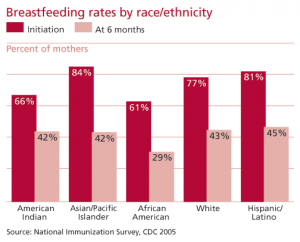

These cultural differences in the meaning of breastfeeding to white and African American mothers are reflected in breastfeeding initiation statistics. White, Asian, and Hispanic mothers have roughly similar rates of breastfeeding initiation, while African American and American Indian mothers have lower rates (above).

The importance of cultural differences and how they play out in breastfeeding practices has also been explored in studies of immigration. A study by public policy professor Christina Gibson-Davis and Jeanne Brooks-Gunn, co-director of the Columbia University Institute on Child and Family Policy, found that breastfeeding rates among Hispanics were related to the mother’s country of birth. If the mother was born outside the United States and immigrated, she was more likely to breastfeed. Furthermore, for each additional year the mother had lived in the United States, her odds of breastfeeding decreased by 4 percent. These patterns suggest that the more acculturated the mother is in U.S. society, the less likely she is to breastfeed.

However, another study examining Vietnamese immigrant mothers in Quebec contradicts that model. Medical anthropologist Danielle Groleau and colleagues interviewed 19 Vietnamese mothers who immigrated to Quebec. They argue that geography and culture combine to create a context in which mothers decide not to breastfeed. In the Vietnamese traditional understanding of post-partum medicine and breastfeeding, women are said to suffer from excessive cold, which leads to fatigue, and the production of breastmilk that isn’t fresh. In Vietnam, new mothers are cared for by extended family for several months post-partum in order to balance their health and allow them to produce “fresh” breastmilk. However, Vietnamese immigrants in Quebec had low rates of breastfeeding primarily because the lack of social support and caregiving that would have been offered in Vietnam wasn’t available in Canada. They saw bottlefeeding as optimal for their babies because their breastmilk wasn’t fresh. These mothers weren’t adopting the dominant Canadian cultural model and had retained their own cultural ideals about breastfeeding.

Problematic Science

The understanding that “breast is best” is based on scientific studies linking breastfeeding to a variety of health benefits. The breastfeeding recommendations issued by AAP, the World Health Organization, and other public health organizations state that breastfeeding increases IQ and lowers the likelihood of ear infections, diabetes, respiratory and gastrointestinal illnesses, and obesity. These benefits are transmitted to the public as unambiguous scientific findings. But upon closer examination, the science behind these claims is problematic.

Political scientist Joan Wolf, in the Journal of Health Politics, Policy, and Law, argues that the benefits of breastfeeding have been vastly overstated. Perhaps the largest problem is that it’s impossible to conduct a controlled experiment—by asking some mothers to breastfeed and others to formula-feed—so all studies are observational. In other words, researchers have to tease out the characteristics of those who decide to breastfeed from the benefits of breastmilk itself. Mothers who choose to breastfeed may also promote a host of other health-protective and IQ-promoting behaviors in their children that go unmeasured in observational studies. The problem becomes even more pronounced when trying to examine the long-term health benefits of breastfeeding because there are even more potential unmeasured factors between infancy and adolescence that contribute to overall health.

Some researchers have attempted to control for potential unmeasured factors by studying the health of siblings who were fed differently as infants. Although these studies can’t discern why the mother breastfed one child but not the other, they do control for parenting factors that go unmeasured in other studies. For example, a recent sibling study by economists Eirik Evenhouse and Siobhan Reilly, based on data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health, suggests correlations between breastfeeding and a variety health benefits, including diabetes, asthma, allergies, and obesity, disappear when studying siblings within families. Only one outcome remains significant—that the breastfed sibling had a slightly higher IQ score (siblings who were ever breastfed scored 1.68 percentile points higher than siblings who were never breastfed).

Most of these studies can be critiqued for exaggerating the importance of small and weak associations; however, although these correlations are weak, they are consistently found. Furthermore, despite weak correlations, biomedical researchers have in some cases been able to identify the biological mechanisms that offer infants health protection. For example, one very consistent finding seems to be that breastmilk lowers the incidence, length, and severity of gastrointestinal illness because gut-protective antibodies, including IgA and lactoferrin, are passed from mother to child through breastmilk.

To be sure, not all biomedical research on breastmilk identifies beneficial biological mechanisms. Medical researchers have found breastmilk to contain HIV, alcohol, drugs, and environmental toxins. How these findings are used by public health officials varies. To take the case of HIV, in parts of the world with high rates of infection, public health officials debate whether to recommend breastfeeding or not. Even if the mother is HIV positive, some argue the infant may gain other protective health benefits from breastmilk, especially in resource-poor countries plagued by inadequate water supply, limited refrigeration, and poor sanitary conditions. In the United States, however, mothers are now routinely advised to bottlefeed if they have HIV. Mothers in the United States are also advised to stop nursing if, for medical reasons, they have to take medication that passes through breastmilk and may be harmful to the baby. Nevertheless, the overwhelming public health message continues to be “breast is best.”

Breastfeeding for Public Health

The “Babies Were Born to be Breastfed” public health ad campaign was designed to educate the public about the benefits of breastfeeding and the risks of not doing so. The campaign hoped to achieve goals established by the Department of Health and Human Services “Blueprint for Action on Breastfeeding”—75 percent of mothers initiating breastfeeding and 50 percent breastfeeding their babies until five months by 2010.

But the campaign, along with doctors’ advice and parenting publications, treat the decision to breastfeed as an individual choice without attending to the social and cultural situations in which this choice is made. The decision to breastfeed is shaped by a variety of social and cultural factors, including doctor-patient interaction, social support networks, labor force participation, child care arrangements, race and ethnicity, class, income, and education. Treating breastfeeding and other parenting practices as individual, decontextualized choices holds mothers solely responsible for their children’s health.

In an analysis of discussions about mothering, bioethics professor Rebecca Kukla argues that we hold mothers accountable for all kinds of childhood health problems, including obesity, malnutrition, birth defects, and behavioral disorders. The fact that many of these health problems are disproportionately overrepresented among the lower class further demonizes poor, working-class mothers. Furthermore, by focusing on mothers’ individual responsibility for child health and well-being, we aren’t attending to other, more egregious societal issues that negatively affect children, such as pollution or lack of adequate health care.

Scientific research on infant health is incredibly important. However, as these findings are reported to the public, shaped into recommendations, and developed into public policy, it’s important to view them with a critical eye. We need to consider the unintended consequences of breastfeeding promotion and other recommended parenting practices. These recommendations and policy based upon this science may inspire stress and guilt in mothers, especially poor and non-white mothers, when they don’t measure up.

Recommended Resources

Orit Avishai. “Managing the Lactating Body: The Breast-Feeding Project and Privileged Motherhood,” Qualitative Sociology (2007) 30: 135–152. Challenges the notion that breastfeeding is empowering and pleasurable through interviews with middle class mothers.

Linda M. Blum 1999. At the Breast: Ideologies of Breastfeeding and Motherhood in the Contemporary United States (Beacon Press, 1999). Uses in-depth interviews with mothers and analyses of popular advice literature to explore how mothering and breastfeeding vary by race and class.

Eirik Evenhouse and Siobhan Reilly. 2005. “Improved Estimates of the Benefits of Breastfeeding Using Sibling Comparisons to Reduce Selection Bias,” Health Sciences Research (2005) 40: 1781–1802. This quantitative analysis of sibling pairs suggests observational studies may have overstated the long-term benefits of breastfeeding.

La Leche League International. Breastfeeding Statistics (La Leche League International Center for Breastfeeding Information, 2003). Summary of cross-national breastfeeding initiation and duration rates.

Joan B. Wolf. “Is Breast Really Best? Risk and Total Motherhood in the National Breastfeeding Awareness Campaign,” Journal of Health Politics, Policy, and Law (2007) 32: 595–636. A forceful critique of the public health campaign to promote breastfeeding, as well as the science behind it.

Comments 19

kv617

December 5, 2009While I 100% completely agree that there are socio-cultural contexts and expectations for mothers to breast feed, It is unnatural to give your child anything else.

Support for nursing mothers should include the right to have access to a pump and bottles etc, that can be borrowed from a hospital (as these materials can be sterilized and re-used), friend, etc.

I think that as a nation, we need to give the best support to mothers and thier children, and that means making sure all mothers have the ability to breast feed (if they choose), or at least have their children drink breast milk from a bottle (which can be administered by anyone, including the father). This can be done through the distribution of said pumps and making sure that mothers, and fathers have access to maternity/paternity leave to take care of their children.

Obviously women who drink alcohol or use drugs have other more important issues regarding their own health and well being than breast-feeding their child. Better social services that will help pregnant/nursing mothers kick the habit, can only serve to better the community.

It is pointless to argue whether or not breast feeding is the best form of nutrition for your child because 100% hands down it is for the vast majority of women and children. The issue here, should be making sure that all mothers regardless of race and class have the opportunity to give their child the best start in life that they can, and this includes breast feeding.

As a nation, we need to do a better job in allowing new parents to have more time off from work, better access to health care and social services, as well as the materials necessary to make breast milk the primary source of nutrition for a baby. It is unhealthy and unnatural to drink milk from a source that is not your own mother.

kv617

December 12, 2009I suppose that I don't think people should have children if they are not willing to put their children's needs first. Obviously I don't expect women to breastfeed if it causes them illness, severe injury or infection, because this is not good for the mother or the baby.

It certainly is far less natural to attach a machine to a cow, and drink her milk (which is intended for her baby (who was most likely stolen and sent to a veal farm) and drink that instead. Breast pumps help women to stimulate lactation for women with a low milk supply, or who have not just given birth. A breast pump may be used to relieve engorgement, a painful condition whereby the breasts are overfull, possibly preventing a proper latch by the infant. If the mother needs to take medication that affects the breast milk and may be harmful to the infant, the mother may "pump and dump" the breast milk to keep up her milk supply during the time period that she is on the medication and may resume nursing after the course of medication is completed. Finally, pumping may be desirable to continue lactation and its associated hormones to aid in recovery from pregnancy even if the pumped milk is not used.

It also makes it possible for working parents to make sure that the nutrients received by the baby are the best it possibly can be.

This is why I advocate that all parents should have extended (paid) leave from work (for all jobs), that pumps (manual or electric) are provided, and that moms are edcuated about the benefits of breast feeding.

Whether we like it or not, as women, if we did NOT have the technology or substitutes to make it possible to bottle feed, we would all have to breast feed. Just because it is "inconvenient" or "annoying" doesn't mean it isn't the right thing to do.

kv617

December 12, 2009I will start out by saying that I was not breast fed as a child. My mom is a nurse and my dad is a technician. At that time (80s), however, working women probably did not have the rights and benefits that working women do today in regards to child care. My parents did a great job, and I turned out okay.

It was never suggested that anyone was not a "worthy" parent because they did not breast feed. It was stated that they should consider the needs of a child before they had one. This need includes appropriate nutrition. It is also true, but unmentioned in this article, that infants who breast feed are less likely to catch illnesses such as ear and respiratory infections, reduces the risk of SIDS and reduces risk of uterine, ovarian and breast cancer in the mother. Breast milk is also not "merely" better than formula or other milk beverages, Sugars other than lactose found in formulas have a vegy negative effect on a child's teeth and digestion. There is also not enough fat in other mammalian milks to support the proper growth of an infant. When you bring a new person into this world, you are responsible for their well being and outcome. This involves choices you make as a parent that can, and will impact your child, Including your own health, as a parent, (which is why it was never suggested that breast feeding is the only option).

As a professional social worker, and a person who has been in the care of children for many years, I am well aware of the situations faced by parents in our "current day." The majority of families require two incomes, and those that rely on one, are often in very difficult cirucumstances that can put other family needs ahead of the individual baby's. If there is no food on the table for mom to have, kids don't get any either. However, for working mothers, if they want, to be able to use time on work, and have free access to the tools that will make it possible, easier and less stressful for working women who think that it is the best choice. Also, as a social worker, I am well aware of the impact of not being able to spend adequate time, or offer appropriate developmental care with your child. The early years of development are the most important, and fundamental to get right.

Once you have a child, the world isn't about you, or your needs. Clearly, parents need time to themselves, time to rest, and time to take a break now and then. Having children is stressful, so is providing for them. Sometimes, there can be issues that may impact a woman's ability to breast-feed that are more important than the breast feeding itself.

There are other things in life that people "choose" to do, that are not "wrong", but are less correct or appropriate than other options in the majority of situations. If this seems "essentialist" or "absolutist" to you, that's fine. It was not meant to mean that 100% of all mothers everywhere need to breastfeed or they are terrible mothers who should have their children taken away, far from it. The general meaning of conveyance was to support the appropriate human development from day one.

If you don't want to breast feed, fine. Its not my kid. I was just stating reasons that it should be supported, and shoud be advocated for in the majority of situations. Having a child is a life long commitment, and yes, some women don't want to breast feed, I would just ask these women and parents who decide not to, to sincerely and completely examine their reasons for not doing it, because the economic (you don't need to buy anything, less medical costs for childhood diseases), health, nutritional, social and developmental benefits are quite important.

classwarrior

December 18, 2009This article has several deep flaws. The first is that the author talks about breastfeeding initiation, but not duration or whether the mother breastfeeds exclusively. The latter two are much more important when discussing breastfeeding. Focusing on initiation leads one to believe that women are breastfeeding much more than is actually the case. In the United States, wompen tend to not exclusively breastfeed infants, especially after the infant turns three months of age. This is a result of our country's lack of a paid maternal leave policy. This needs to be mentioned in any discussion of the social context of breastfeeding in the US. Looking at initiation rates is misleading, at best.

The article ignores completely the political-economic context of breastfeeding in the US. In addition to the absence of paid maternity leave, infant formula companies undertake a huge marketing campaign to get women to use their products. This marketing effort has a profound effect on duration of breastfeeding. It is not mentioned at all in this article.

The effort to downplay the benefits of breastmilk is not convincing. While I sympathize with the critique of IQ studies - I don't feel that reducing human capabilities to one number is a helpful or accurate way to analyze ourselves - most of the other health-related studies appear solid. Human infants have been drinking breastmilk for all of human history, with the exception of the last century. Of course it's going to be better for them! This is not to say that artificial formula is poison, but that it is probably not possible to improve on the beverage our infants have enjoyed throughout our evolutionary history.

Finally, the main reason breastfeeding rates have increased around the world is the presence of strong social movements acting against the predatory practice of formula companies, not the "ideology of intensive mothering". Intensive mothering did not make the World Health Organization, UNICEF, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and other public health agencies recommend exclusive breastfeeding - social movements did.

There is more I could say, but I will stop now.

Jon Smajda

December 18, 2009Anyone following the comments on this thread may be interested in the Contexts Podcast interview with Julie Artis about this article.

joschmidt

December 18, 2009Regarding the drop-off in exclusive breast-feeding rates at three months - the provision of parental leave entitlement may be one factor, but if you talk to actual woman who actually breastfeed, some of them do find it restrictive, and may choose to cease exclusive breastfeeding for reasons of their own. In New Zealand, breastfeeding rates also drop at three months - yet formula manufacturers cannot market formula for those under six months. Marketing cannot therefore be the sole, or in this context even a dominant factor.

While those marketing formula in the third world (the context in which WHO, UNICEF and others work) are working to the detriment of infants and their families, in the first world this is usually the case - with appropriate information and support, formula feeding simply does not present the same risks to infants as in third world context.

Furthermore, presenting formula manufacturers as 'predatory' is somewhat disingenuous. People have sought alternative to (exclusive) breastfeeding across cultures and history - formula and the related equipment represents one of the few successes in this regard. Another successful alternative is cross-nursing, but in contemporary western contexts this has become an extremely marginalised activity.

I would not dispute that breastmilk is more nutritious, but I do think that other 'benefits' such as those linked to issues such as ear infections and gastro-intestinal problems could well be ameliorated with appropriate education around formula feeding. Until that happens, we will never really know what happens because of formaul itself, and what happens because parents who formula feed aren't appropriately educated and supported. I also have issues with how the health 'benefits' of breastfeeding are reported, which often mask the actual levels of these benefits.

Research suggests the 'breast is best' message has penetrated the majority of its target audiences with effectiveness. In spite of this, breastfeeding rates have plateaued, and do not appear to be increasing. In light of this, it seems reasonable to assume that parents are making decisions based on a number of factors. Again, I would suggest that formula represent a viable alternative to breastmilk that some parents seem to find preferable, for a range of reasons. Rather than marginalise them, it would seem that some of the money being spent on 'breast is best' campaigns (which seem to have reached market saturation) might be better directed at educating and supporting those parents.

classwarrior

December 20, 2009These are the reasons (not necessarily in order) breastfeeding rates are so low in the United States:

1. The lack of paid maternity/family leave coupled with the need for most women to work outside the home. This is absolutely the main reason most women do not breastfeed beyond three months, or, in many cases, even less. I'm not sure why there is even a debate about this. Women in the US get three unpaid months of maternity leave, which many working-class and poor women cannot take because their families depend on their income. This is especially true for single mothers. In addition, most work sites are not required to accommodate women who wish to pump at work, so they might have to pump in a bathroom or not at all. Women have no choice but to turn to formula to provide nutrition for their infants.

In other words, being able to breastfeed exclusively for six months (as recommended by the AAP, WHO, UNICEF, the Surgeon General, and others), let alone three months, is a privilege enjoyed by those who are able to take time off from work and have time to pump while at work. This, in my opinion, is unacceptable.

2. Aggressive marketing of formula by its manufacturers. Ever seen a picture of a breastfeeding mother/infant pair in a mainstream parenting magazine? Probably not. But you'll see a lot of bottle feeding. This is a small example of this marketing at work. Formula compaines aim their marketing powers not only at individual women, but also by working with hospitals. They promote their products in a fashion similar to pharmaceutical corporations. Their specialty is providing free formula for the doctors to give away. Describing all of their marketing practices is beyond the scope of a brief comment.

By the way, it is not disingenuous to refer to the marketing practices of formula manufacturers as predatory - I can't think of a better word to describe it. When you're trying to sell your product by marketing it aggressively in countries with large proportions of their population not having access to clean water, sending in representatives to hospitals in so-called third world countries posing as nurses, or billing your product as superior to breastmilk, then your actions are predatory (or insert your own negative descriptor, if you wish). See books by Gabrielle Palmer and Naomi Baumslag and Dia Michels for more examples. Thankfully, these companies can't get away with as many of these activities now because of the vigilance of groups dedicated to monitoring their practices.

3. Lack of a support network for women who want to breastfeed. Women often have to go it alone when it comes to breastfeeding. Traditional support networks - ones that would pass along knowledge of how to breastfeed, among other things - do not exist to the same degree as in the past. Physicians receive little to no training in breastfeeding. There are not enough lactation consultants in healthcare facilities. Nearly all hospitals in the US allow formula companies to give away their products in their maternity wards.

4. The emphasis on breasts as sources of male pleasure. When women use them for other purposes (i.e., feeding infants), it is seen as an attack on male ownership of breasts. Combined with our country's prudish attitude toward sex, breastfeeding is seen in a negative light, despite laws in most states protecting the right of women to breastfeed. Linda Blum (cited in the above article) wrote about this - her analysis is more or less correct, if a bit overstated.

5. As stated in the above article, African-American women face particular obstacles with breastfeeding - see above for more info.

---

As we can see, breastfeeding is a challenge for women in this society, to say the least.

What's the solution? If the US had six months of paid maternity leave, its breastfeeding rates would jump. We should train and hire more people to help women with breastfeeding and promote the establishment of Baby-friendly healthcare facilities (as defined by UNICEF/WHO). Make it illegal to market formula in hospitals, along with other curtailments to this industry. These changes, especially the first, will happen a)when pigs fly or b) we have a better, more rational socioeconomic system. I'm pulling for the latter.

Despite what the above article states, low breastfeeding rates are a serious public health problem - the government is correct to focus on it. However, teling women to breastfeed but not helping to make it more realistic is not a good policy.

theresaellie

January 29, 2010Although I am not yet a mother, I find the topic of motherhood a very interesting subject worth discussing. I myself was not breastfed, but have not suffered from any serious illnesses and am intelligent enough to be an honors student in college. I found this article to be incredibly enlightening to the difficulties of breastfeeding. I have always assumed that once I became a mother, I would breastfeed my child for at least a year. Being a young adult, I never considered the logistical difficulties of being able to supply one's child with milk around the clock, while it is not socially acceptable to bare one's breast in public for any purpose. It is interesting that sex is portrayed in popular culture and advertising every day, but a mother providing nourishment to her child in public is unacceptable. I can now understand why some women may feel like it is too difficult to manage their newly busy lives and incorporate time to breastfeed. There need to measures implemented in work places and other places of business that allow for women to breastfeed their children in nice, comfortable places if they are going to be attacked for doing so publicly. I certainly hope that better procedures are in place once I have children so that I can work to support them, and carry out my other duties as a mother and citizen, all while being able to provide them with the greatest level of nutrition. With all of the money being spent to promote the benefits of breastfeeding and educate women, there should also be money put towards finding a solution to the issues discussed above.

momonnet

February 5, 2010I thought that this article was one of the most sobering and neutral writings on the topic of breastfeeding. It is not anti-breastfeeding at all so I don't see any need to attack it. Artis does raise a number of otherwise silenced points in the breastfeeding debate which is hardly a debate at all in my opinion since the only acceptable choice for a woman is to breastfeed. I was not surprised to see the usual comments by disbelieving readers about how breastfeeding is natural and therefore right. "Natural" doesn't exist, only constructions which are so engrained that they seem "natural" govern every culture. To this respect I can only recommend books such as Anthropology of Breastfeeding: Natural Law or Social Construct by Vanessa Maher. Like other readers, however, I also share the view that true feminists want choices for all women and this includes the right to breast-feed or bottle-feed without essentialist standpoints. We should be ready to defend a woman's right to breastfeed in public, the maternity leave to carry out her wishes and also recognize that sometimes the risks or disadvantages do outweigh the benefits of breastfeeding and that some women cannot breastfeed at all. Though breastfeeding rates aren't as high as 100 years ago and not as high as in most developing countries today we still have healthier births, babies and mothers here and today. Supplementing is not new, for various reasons some babies have always had to use it in many cultures. Formula is the best alternative to date and is combined with the best medical care we have ever had. Women are also very different than in previous centuries and I believe that their participation in society as more than child-rearers is vital and desirable. As far as the comment about how parents should not choose to have kids if they won't put them first, who is to say what "putting kids first" actually means? It is only in this century that such a large cohort of women actually have time to do anything more than feed their children. They can actually play, teach, and take them places. Though I still think that only a limited number of women truly "choose" to have children at all because this society still puts undue pressure on women to marry and have children. I think that a woman who doesn't want to breastfeed is entitled to have a family too. Is no life in the first place really better than a bottle-fed baby?

zcato

May 6, 2010This article was a great middle ground presenting many of the other factors going into whether or not a mother chooses to breastfeed her child. I trust in many of the "observational findings" that studies have shown, but I definitely wouldn't call them scientific fact, as the ad campigns declared. That being said, it's hard to say "we found this to generally be the pattern but it's not definite, but breastfeeding is still probably a good idea" on a poster and have anyone pay attention to it.

I definitely agree with those who wish to be able to breastfeed in public. I think that the idea that breastfeeding is indecent must arise from the american obsession with sexuality, where anything that has been associated with sex can never thereafter be separated from it, no matter what the context. Attaching this label of indecency to a woman's body creates the air of degradation that we see being so prevalent.

Bianca

August 5, 2012I am having problems with me breast feeding my daughter in church, in the sanctuary. I am not taking this lightly.

Lacey

March 25, 2013This is nonsense. Seriously. We have to worry about emotional "guilt" trips because the facts are the facts and they're being- gasp- taught as facts? WHAT? Women are so selfish and emotionally out of control these days. We demand that standards be set in unreasonable ways so that we don't feel "pressure" or "guilt", and then you say, "oh, for the sake of the poor people". Pah-lease! So we all have to suffer like poor people even if we're not? Weird. I'm poor and I don't expect rich people to give up the things they have because I don't have them. And I have managed to breastfeed 3 babies for 2 years each, poor, poor, poor the whole time. Doing great.

If you're doing the best you can as a mother, whatever that leads you to doing, you will have a clear conscience. If you're not, humble your proud self and learn what you're doing wrong. Find a way to change it. It can always, always be done. God wants us to do what is right. He will take care of it.

What you're really pushing for in this article is that women should be able to make whatever decision they want, no matter who it hurts, without being viewed as "bad". We have already gotten WAY TOO FAR down that track! STOP ruining women!

Helen

March 28, 2013Formula feeding is not hurting anyone Lacey. This has gotten ridiculous now and there is serious pressure put upon women to breastfeed. If they can't do it, they're made to feel like a failure. I go to breastfeeding groups (I combi feed my 8 month old but breastfed for a long time) and I see women who haven't had any sleep in months and are tearing their hair out. Absolutely breastfeeding is brilliant but not if it leads you to a nervous breakdown or worse. There is no support for these mothers unless they choose to continue breastfeeding - otherwise they're out of the club. It has gone too far and it will take something bad to happen for people to take a step back. A happier mom is one who can share the responsibility. After all, it takes a village to raise a child.

Another one is that women must now go back to the middle ages and use cloth nappies instead of the wonderful disposables. It feels like there is something bigger in play here... that for some reason they want women to be completely answerable to their kids, rather than the confident independant role model mothers that they can be. There's nothing wrong with breastfeeding, there's nothing wrong with formula feeding, women should simply support eachother regardless of whatever choices they've made for whatever reason. You successfully breastfed 3 babies for 2 years, wonderful! Don't judge those who can't or won't. There are 'facts' being thrown around with no figures to support them.

I'm a middle class mother who will not be going back to work so I do not have that pressure. I could continue to exclusively breastfeed if I chose to but I do not feel that it is in my childs best interest. I feel it is much better for him to also have a close relationship with his Dad and his grandparents. This, selfishly, also means that I can get a great nights sleep and be wide awake the next day to deal with my childs every other need. I can play with him, I can teach him, I can give him a wonderful life without having to stop every hour and a half for a half an hour to feed him. Some of the kids at the group I go to scream as soon as their mother turns her back for a second. How is this good for the child? My child is safe and happy and warm and fed and he knows it.

Please all, simply stop being so judgemental.

Anslee

April 26, 2013I found this article to be fairly well written, and I enjoyed it. It has a hint (just a hint) of leaning in the way of anti-breastfeeding. That is ok, though, everyone is entitled to their own opinions. If you want to breastfeed, great! Go ahead. If you want to but can't, that is fine too, as there are ways around this obstacle that are not formula feeding. If you want to formula-feed, this is fine a well. I just think it is very important that everyone be well-informed, to make the best decision, for you. Hearing both sides is imperative in making an informed choice. Breastfeeding does not make your child clingy, she/he can grow up to be quite an independent person. Clingy-ness, can be inherited, as well as learned, but it is not learned by breastfeeding. Formula-feeding your child can also have them grow up to be an independent person, but, a formula-fed child can also be clingy(any child can). I do not think we should make anyone feel guilty for their choices as parents, unless it was truly something universally immoral. Formula is not immoral, as it is necessary for some families (adopted children, women who can not breastfeed, etc.). You should not be bullied because you cannot do something. You wouldn't bully someone who is paralyzed, for using a wheelchair instead of walking, would you? Walking is the natural thing to do, and it has health benefits, but if you can't walk, that's that. I do however, see how people get angry with people who just don't give a darn what is best for their child, and do no research, and just give their child formula. Why be in a wheelchair if you are able to walk? This does not make you a bad parent though. If you found that formula-feeding was best for you and your child, that's fine! That does not mean you can't be a good parent. You may be an excellent parent. Parenting is not so black and white as to be judged by whether or not you breastfeed. As far as health, breastmilk is much better for baby than formula, and generally, breastfed babies are healthier than formula-fed ones. Before you call BS, this is true, and keep in mind that like I said, there's no black and white. Breastfed babies can still get sick, they can still get very sick. Formula-fed babies can also be very healthy. Breastfeeding does create a great bond between mother and child, but if you are formula-feeding, don't worry! Breastfed babies have a way to bond with dad/other mom/caregivers, that also works for formula-fed babies. Skin to skin contact is very important. You can put baby on your bare skin, and cuddle or whatever you may like to enhance the bonding. Skin to skin contact is an important part of developing a bond with anyone, so why not do it with baby? Lastly, I would like to point out that just because you all day, five days a week, doesn't mean you can't breastfeed. In addition, if you work and breastfeed, this does NOT, mean you will be sleep deprived and pulling your hair out or even feel like doing so. Many women love coming home to baby and having that one-on-one bonding time through breastfeeding. Please, let's all try to work together, as none of us are right or wrong, we just want to make sure that women are making the best decision for them and their baby.

Thank you all.