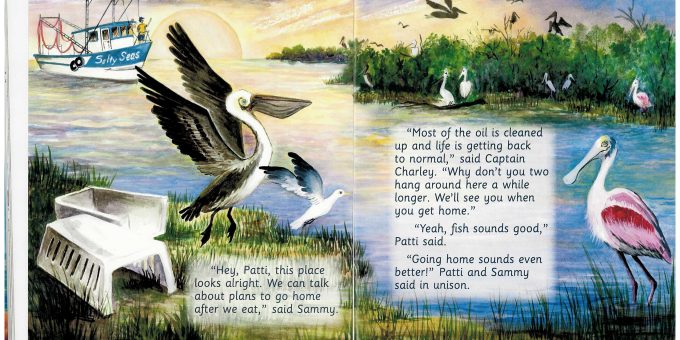

From Patti the Pelican, HIS Publishing Co. saltyseasandfriends.com/pattiPelican.html

D is for disaster

A 6-year-old boy in Buras, LA sits down with his father to read Patti the Pelican and the Gulf Oil Spill. Buras was devastated by the 2010 BP oil spill, and families that live there are dependent on the heavily affected fishing industry. Seven years after the spill, the town is still struggling with its health and economic consequences. As his dad reads about the resilient Patti, the little boy notices that the story doesn’t seem quite right. In the book, somebody (we are never told who) quickly cleans up the spill, scrubs oil from the pelicans, and relocates the dolphins. On the final page, the animals’ human friend, a shrimper named Captain Charley, remarks, “Most of the oil is cleaned up and life is getting back to normal,” before inviting his marine companions to return home—a happy ending.

The illustrations in most of the 23 disaster-themed children’s books we analyzed are colourful and show affected communities easily avoiding or recovering from catastrophe. These books frame disasters (even oil spills) as blameless, naturally occurring events that only temporarily disrupt people’s lives. But every year children’s lives are turned upside down by wildfires, hurricanes, tsunamis, and earthquakes. Irwin Redlener and colleagues estimate that in Louisiana and Mississippi, Hurricane Katrina displaced as many as 450,000 people for longer than six months, including 163,000 children—36% of the total. In their book, Children of Katrina, sociologists Alice Fothergill and Lori Peek show that even years later, children continue to experience housing instability and signs of trauma, which affect their abilities to heal emotionally, succeed academically, and thrive socially.

Like many children’s books, Patti the Pelican is presumably written to provide an uplifting moral: Affected communities will bounce back. But this is a privileged idea that does not consider the fact that children negotiate tremendously difficult and painful experiences. The sorts of books we studied are resources for parents to help shepherd children through the uncertainty of disaster, but how exactly do they present the challenges of disaster? What tools do these books provide children to understand environmental and social impacts, and to become engaged in their own, and their families’, recovery?

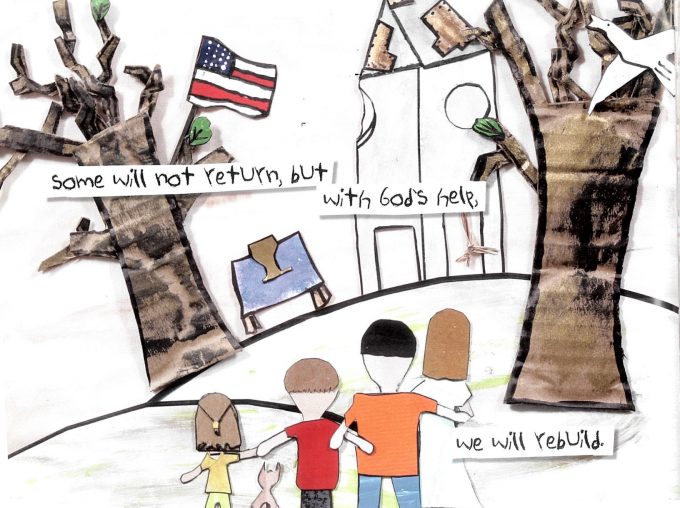

Many of the books portray children as passive and suggest they should be shielded from—rather than involved in—the disaster affecting their communities. In Erin and Katrina, adults withhold information about what is happening during the storm; the main character, Erin, learns about Hurricane Katrina only by watching the pounding rain and TV coverage of the event, not by discussing it with her family. This runs counter to established best-practices in the field. Fothergill and Peek, along with disaster scholars William Anderson, Robin Cox, and others, argue that although children, because they are small and have little autonomy, are vulnerable during disasters, they are not passive victims. Instead, children have the capacity for imagining practical and creative ideas for helping their peers, families, and neighborhoods that could contribute to community recovery. For instance, as part of the SHOREline project in Gulfport, Mississippi, a group of local high school students devised a program to provide free childcare and sustainable food sources to disaster-affected areas, including their own city.

The omission of culpability is also endemic in children’s books about disaster. In Story of a Storm: A Book About Hurricane Katrina, “Katrina pushed the water and washed away places we knew… Katrina drowned cities and made men cry.” But in New Orleans, the storm didn’t actually cause this devastation. It swept through the Gulf and hours later, the levees cracked and flooded the city due to faulty construction. The human decisions leading to the levee failure are never mentioned in the book. The Katrina disaster is thus an unfortunate event, but readers are left without possibilities for prevention. Even in Patti the Pelican, British Petroleum, Transocean, and the Deepwater Horizon are never named; and the hard work local fishers did, operating booms and skimmers to contain and recover the oil, is made invisible.

Probably the most common theme in these books is the tendency for family and community disaster recovery to be uncomplicated. This is counter to Heather Getha-Taylor’s research on hurricanes and Matthew Carroll and colleagues’ work on wildfires, all of which frame disasters as “wicked problems” in which resolving one problem often introduces an array of new ones. Quickly rebuilding housing, for example, may gentrify an affected area or may negatively impact the sense of community, harming future resilience. In Oil Spill! Disaster in the Gulf of Mexico, “Scientists think most of the oil spill cleanup will happen through nature, not people. Oil at the surface is broken up by waves. It evaporates in the air. Oil slowly breaks down in the water, and bacteria eat it.” And, in the book Hurricane Wolf, a mother reassures her child that the “plants and trees will grow back… and we can fix everything else.” Once the hurricane has passed, the book’s illustrations give no indication of any lingering problems—not even downed branches or power-lines. For families displaced from their homes, disaster recovery is painted as straightforward, requiring little effort—an image that contradicts the hardships from which children and their families are struggling to emerge.

As often as recovery is seamless, it is entirely absent. In Freddy the Frogcaster and the Huge Hurricane, the protagonist, Freddy, jumps into action by boarding windows, warning neighbors, and packing his family’s emergency kit when a hurricane threatens his town. After it has passed, Freddy notices: “Trees were down. Cars were flipped over. Plenty of roofs needed repair. But all that could be fixed. The good news was—everyone was safe!” While Freddy helps with risk mitigation, the recovery phase of the event is missing entirely.

In their research on PTSD after wildfires, Brett McDermott and colleagues note that at least one-quarter of disaster-affected children experience intense psychological distress from relocation and loss. But the children’s books rarely discuss how individuals and communities approach the recovery phase of disaster beyond invoking “rebuilding” and “fixing” property. Gullah: The Nawlins’ Cat, focuses entirely on the emergency phase of Hurricane Katrina, and concludes the story as the cat and his human companion are airlifted from the disaster. In The River Throws a Tantrum, about the devastating 2013 Southern Alberta Flood, the focal child vividly describes his feelings of anxiety and sadness during a period of family separation, but the book quickly ends with the family “arriving home and all is ok.”

Disasters like 2016’s Fort McMurray wildfire and 2012’s Superstorm Sandy have had complex environmental and community consequences. By framing disasters as simple, blameless events we leave little space for children to feel empowered, and to engage in the empowering process of community-based problem solving.

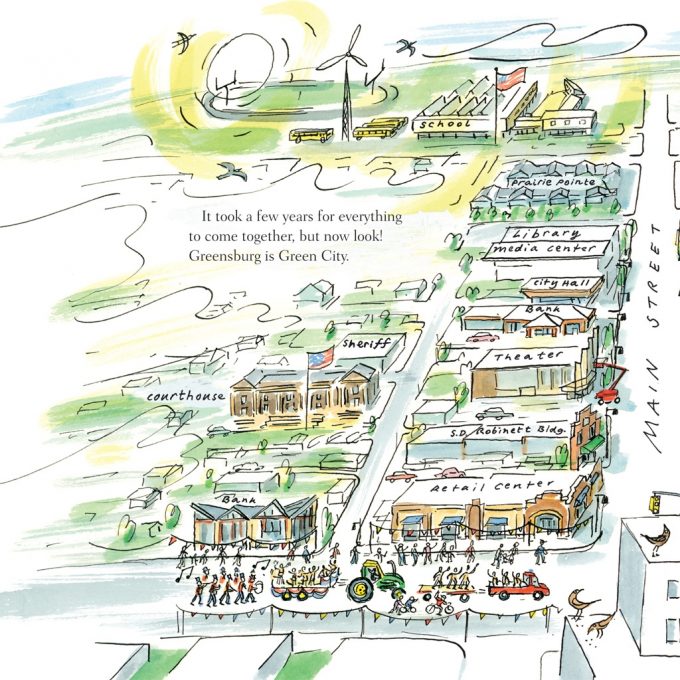

There are, we must note, a few books that allow children space for resilience, empowerment, and innovation. One of these is Green City: How One Community Survived a Tornado and Rebuilt for a Sustainable Future, which recounts the work of the town of Greensburg, KS in recovering from a devastating tornado. Validating feelings of loss, the book remarks that, “Everyone’s past had been swept away. Suddenly the entire town of Greensburg had no future.” But, in the pages that follow, the community—including its children—comes together, working hard to build a more sustainable city. The children even “Became experts in environmental science,” and eventually “rebuilt into one of the greenest towns in America.” Interestingly, the three books we found that attempted to plug into children’s capacity for resilience featured true stories and the work of actual survivors.

Children’s books on disasters generally explain them as brief social and environmental problems with easy solutions and few lingering consequences. In doing so, it is unlikely these books are consistent with the lived experiences of children in affected regions, for whom disasters continue to affect their housing, health, family, and education for years if not decades. Patti the Pelican does nothing to help the little boy in Buras, LA understand why dead animals continue to wash ashore, why his parents are still without work, or why some of his friends have moved away.

We need children’s books that present disasters as both social and environmental problems, that reflect children’s lived challenges post-disaster and encourage them to become involved in lifting up their families and communities. In our view, books on disaster should help children wrestle with the “whys” of disaster and encourage them to appreciate and participate in the hard work, developing clever ideas that produce a more equitable recovery.