The “Tipi Cover” in Settler Colonial Context

The summer 2025 cover of the Contexts journal features a picture of a modern tipi in a dark, outdoor, mountainous setting. The tipi has light inside and a rack of feathers outside. There are no humans or any other materialistic items. This tipi is used for non-Native recreation. The main title on the cover, “erasures and defiance,” was selected to reflect two included articles that address Native American topics. The representations apparent in the Contexts cover image conflict with the stated intent of the title.

To unpack this conflict, we situate this image in the context of settler colonialism, which is characterized by the literal and figurative erasure and dehumanization of Native Peoples. Settler colonial societies, such as the United States, seek to eliminate, replace, and erase Native Peoples, using both literal and figurative means, in order to legitimate taking possession of the land. The means range from the physical killing and removal of Native Peoples to limiting the sovereignty of Native nations, forced assimilation (e.g., residential schools), and erasure from the social representational landscape (i.e., cultural ideas and images). Settler colonialism is not a historical event; it is an ongoing process of elimination that is evident in Contexts’ use of the tipi image coupled with the erasures and defiance title (e.g., McKay et al. 2020; Wolfe 2006).We contend that there are three primary ways that the tipi image and title reflect and reinforce settler colonialism. They omit and misrepresent Native Americans by erasing them as contemporary people, reifying historical representations of them as “people of the past” (i.e., as no longer existing) and homogenizing Native nations and their cultures (i.e., erasing their immense cultural diversity). These omissions and misrepresentations of Native Americans contribute to the harm Native Peoples experience. Below, we elaborate and provide evidence for each of these arguments, and then we conclude by making recommendations to the field of sociology and academia more broadly.

Omitting and Misrepresenting Contemporary Native Americans

To understand the omission (i.e., erasure) and misrepresentation (i.e., stereotyping) of Native Americans, one must first consider the commonly held stereotypes (i.e., cognitive associations) people have created about the group. These stereotypes reflect the publicly available social representations (i.e., narratives and images) people associate with the group. Research, for example, reveals that Native Americans are rarely depicted as contemporary people and are most often depicted as people of the past (e.g., Dai et al. 2025; Davis-Delano et al. 2021; Fryberg et al. 2024). A study with 38,000 Americans revealed that approximately two-thirds hold the implicit bias that Native people are people of the past (Dai et al. 2025). Moreover, non-Native people have learned to associate particular signifiers with Native Americans. Common associations with Native Americans include living in tipis and wearing buckskins and headdresses adorned with feathers, which are stereotypes of Plains Native nations.

Given these research findings, there are several ways in which the use of the tipi image on the cover of the journal is problematic. First, the image omits and erases contemporary Native Americans. While the tipi is contemporary, as noted by the light inside, the intricate machine stitching, and the open entryway and bottom design, there are no accompanying contemporary Native Americans. In addition, tipis are associated with the past. The vast majority of contemporary Native Americans live in houses and apartments, not tipis. So, by using an image of a tipi on the cover to represent “indigeneity” (i.e., the editors’ stated intent), but excluding contemporary Native Americans, the journal cover is contributing to the bias that Native Americans are solely people of the past.

Third, we discovered that this tipi was used by non-Native people for their recreation. This phenomenon of spending time outdoors the way Native Americans stereotypically lived has been referred to as “playing Indian” (Deloria, 1998). It is motivated by an attraction to romantic stereotypical ideas associated with Native Americans, as opposed to who Native Americans actually are. The journal furthers this association by choosing an image that clearly romanticizes Native Americans—choosing a tipi used by non-Native people and an image created by a non-Native photographer. Notably, this decision also erases the fact that there are many extraordinary contemporary Native American artists and photographers.

Fourth, the tipi image is accompanied by the words “erasures and defiance.” Unfortunately, there is nothing in the image that conveys concerns about erasure or that elicits ideas about defiance. Instead, the word erasure is linked to an absence of contemporary Native Americans.

Omissions and misrepresentations, such as those exemplified by the Contexts cover, are evident across educational contexts (primary, secondary, and post-secondary education). In K-12 schooling, the issue is not simply that Native Americans are rarely mentioned, but that 87% of limited representation in public school curriculum locates the group in pre-1900 contexts (Shear et al. 2015). Even within a field such as sociology, which arguably should know better, the same pattern of omission is evident in Introduction to Sociology textbooks intended to represent the knowledge of the field. Notably, while extractive/classic colonialism (i.e., colonization focused primarily on the use of cheap labor to extract raw materials) is covered, settler colonialism is rarely covered, and Native Americans are often omitted from the presentation of statistical findings. Omission and misrepresentation of Native Americans in academia may be one reason for the omission and misrepresentation on the Contexts cover. When academia omits Native American experiences, this contributes to settler colonial processes of erasure.Misrepresenting Native Americans as Homogeneous

The omission of contemporary Native Americans operates in tandem with misrepresentations (Fryberg and Eason 2017). Beyond the stereotypic misrepresentations of Native Americans as bloodthirsty savages, Indian warriors, noble Indians, broken Indians, and casino Indians, there is also a stereotypic misrepresentation of Native Americans as culturally homogeneous. White Americans have created “the Hollywood Indian,” which depicts Native Americans as having a single (pseudo) culture that is most aligned with Plains Native nation cultures. This homogeneity erases the cultural diversity of the more than 574 Native nations in the United States (e.g., Davis-Delano et al. 2021). One aspect of this homogenous Hollywood culture is tipis. The tipi on the cover of the journal exemplifies cultural erasure because it is meant to represent Native Americans, even though many Native nations never lived in tipis. They lived, for example, in longhouses and multistory adobe buildings.

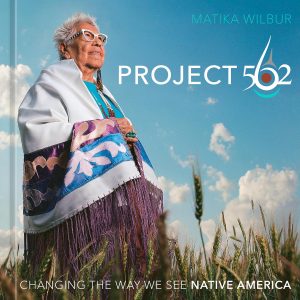

document and photograph over 500 Tribes for Project 562. ©Matika Wilbur, Project 562.

The Harmful Nature of Omission and Misrepresentations

Research reveals that the omission of contemporary Native Americans, misrepresentation of Native Americans as “people of the past,” and homogenization of Native American cultures are harmful. The harm manifests in negative impacts on individual Native Americans, as well as in negative impacts on intergroup relations via fueling non-Native beliefs and policy positions that are less supportive of Native Americans.

Regarding impacts on individual Native Americans, research reveals that the more Native Americans are aware of omission and misrepresentation of their group, the more harm they experience on a variety of psychological wellbeing and life satisfaction measures (Lopez et al., forthcoming). Relatedly, Native American mascots misrepresent Native Americans by stereotyping them as homogenous warriors or chiefs from the past; research reveals that exposure to Native American mascots has negative impacts on Native American youth (e.g., lowers self-esteem and hopes for the future; e.g., Fryberg et al 2008).

With respect to intergroup relations, the more non-Native people believe Native Americans are people of the past, the less consideration they give to the experiences of contemporary Native Americans (i.e., many non-Native people rarely think about Native Americans) (Davis-Delano et al. 2024; Fryberg et al. 2024). Viewing Native Americans as people of the past also leads non-Native people to minimize Native reports of discrimination and to report apathy toward racialized characterizations of Native Americans (Lopez et al 2022) and to the violence Native Americans experience (e.g., high rates of sexual violence against Native women and the epidemic of Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women and Girls; Lopez et al 2024). Notably, these beliefs—contemporary omission, people of the past, and racism minimization—are related to less support for policies that would improve outcomes for Native Americans and Native nations, including less support for resource equity, eliminating racist imagery, and protecting Native nation sovereignty and treaty rights (Dai et al. 2025; Davis-Delano et al. 2024; Fryberg et al. 2024).

Conclusion

In conclusion, the use of the tipi image on the Contexts cover illustrates erasure of Native Americans and inadvertently substantiates commonly held stereotypes. The cover image and associated title are aligned with the settler colonial processes of elimination, erasure, and dehumanization. The image erases contemporary Native Americans, depicts Native Americans as solely people of the past, and erroneously reifies the notion that there is a single homogenous Native American culture. These depictions are common in U.S. society.What would imagery that successfully highlights Native Americans and counters erasure look like? First and foremost, scholars should turn to the photography of Native artists, such as Matika Wilbur, Ryan Redcorn, Meryl McMaster, or Jaida Grey Eagle (to name but a few). Wilbur’s book Project 562: Changing the Way We See Native America (2023) is an excellent example of a contemporary Native person depicting contemporary Native people the way they want to be seen. The book directly counters erasure and offers a keen example of defiance in the representational sense. As a practice, turning to contemporary Native peoples’ work is one way that scholars can counter the ongoing process of settler colonialism.

We hope to inspire sociologists and others who create written and pictorial representations to take action. Toward this end, we call on the field of sociology, as well as the broader academic community, to learn about settler colonialism, contemporary Native nations, and contemporary Native American people more generally. We urge the field of sociology to offer workshops at their conferences and produce guidelines for textbook authors, editors, and researchers that address these matters. By taking these steps, sociologists can increase the quantity and accuracy of representations of Native Americans and contribute to the process of ending the harms contemporary Native Peoples continue to endure.

Laurel R. Davis-Delano (White American) is a Professor of Sociology at Springfield College. Stephanie A. Fryberg (Tulalip Tribes) is a Professor of Psychology at Northwestern University. Both scholars research representations of Native Americans in the United States and the harmful impacts of omission and stereotyping in these representations.

Recommended Resources

Doris Dai, Stephanie A. Fryberg, and Arianne E. Eason. 2025. “Native Now, Equity Now: Implicit Associations between Native Peoples and the Past Predict Reduced Support for Racial Equity,” Psychological Science 36(8). The authors of this article found that most non-Native participants implicitly believe that Native Americans are a people of the past, a belief that is associated with minimization of racism, which is then associated with less support for Native Americans.

Laurel R. Davis-Delano, Jennifer J. Folsom, Virginia McLaurin, Arianne E. Eason, and Stephanie A. Fryberg. 2021. “Representations of Native Americans in U.S. Culture? A Case of Omissions and Commissions,” The Social Science Journal. Advance Online Publication. The authors of this article found that many non-Native participants cannot recall representations of contemporary Native Americans; the representations they can recall include stereotypes.

Laurel R. Davis-Delano, Renee V. Galliher, and Joseph P. Gone. 2024. “Absence Makes the Heart Grow Colder: The Harmful Nature of Invisibility of Contemporary American Indians,” Ethnic and Racial Studies 47(15). Using a sample of White Americans, the authors of this article found that less exposure to representations of Native Americans is associated with less belief Native Americans are contemporary and more belief they are a people of the past, which are associated with less support for Native Americans.

Stephanie A. Fryberg, J. Doris Dai, and Arianne E. Eason. 2024. “Omission as a Modern Form of Bias against Native Peoples: Implications for Policies and Practices,” Social Issues and Policy Review 18(1). The authors of this article discuss multiple research projects that demonstrate that omission of Native Americans impacts Native and non-Native people in a manner that contributes to oppression faced by Native Americans, then provide policy recommendations.

Leilani Sabzalian, Sarah B. Shear, and Jimmy Snyder. 2021. “Standardizing Indigenous Erasure: A TribalCrit and QuantCrit Analysis of K–12 U.S. Civics and Government Standards,” Theory & Research in Social Education 49(3). The authors of this study examine U.S. state standards for K-12 civics and government curricula, finding that some states erase and some affirm Native nation sovereignty.

To read the Contexts editorial team’s apology for the Summer 2025 cover, please click here.