What Do Memes Tell Us about Self and Time during the Pandemic?

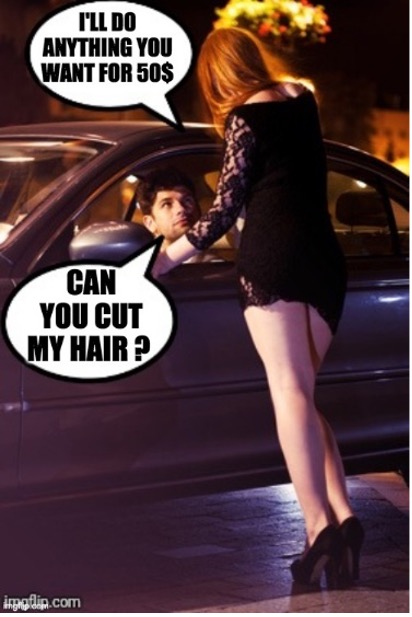

“I want a haircut” has become a rallying sign for people demanding a relaxation of social distancing rules, and a prompt for ridicule among people worried about the pandemic death toll. What’s in a haircut? We are sociologists who study the self and time. During the weeks of social distancing, we have examined online Corona memes in an effort to map how this crisis has modified our experience of time and our presentation of self.

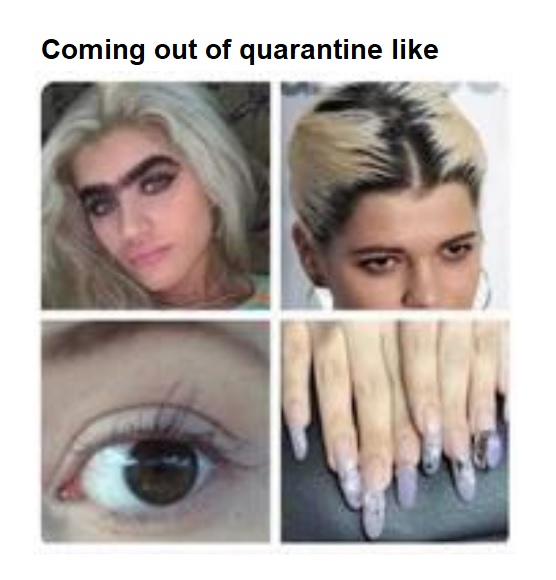

The missing haircut is just the tip of the iceberg in the recent predicament of the quarantined self. Disorderly hair signals disrupted schedules and stressed relationships, going on long enough for hair and despair to grow. A haircut stands for a fresh beginning, a hopeful return to the way things were.

In his influential book, The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life (1959), sociologist Erving Goffman argued that the self is something akin to a theatrical performance in social interaction, not an immutable aspect of personality. Persistent disruption and mingling of our frontstage and backstage encounters undermine the integrity of our self-presentations. According to Goffman, we are constantly staging our identity for the sake of multiple audiences because, in one way or another, we depend on their validation. This identity upkeep unfolds in time and requires a certain sequence of preparation, acting, and audience reception. If temporal order is upset, selves are disrupted, and the ensuing embarrassment can be comic or tragic, depending upon what is at stake (e.g., SNL’s sketch on the pandemic New Normal). In the theater of social interaction, our identities are defined by these performances. Thus, we have a vital interest in the presentation of self. We ourselves assess the efficacy of these performances, along with lovers, colleagues, or strangers in the metro. Apparently minor troubles in self-maintenance acquire existential connotations if they lead to humiliation or other interactional fiascoes.

Daily life confronts each of us with myriad opportunities for success or failure in our presentation of self. With so much at stake, social interaction becomes an information game as individuals and groups engage in impression management. The stakes were high before the pandemic, but COVID-19 wreaks havoc on our performances, though not for all alike. Upkeep of personal appearance suffers. Our clothing (i.e., costume) is often shabby, unclean, and in disarray. Zoom and Google Meet audiences have unprecedented access to what were backstage areas. The visible things in our homes and offices (i.e., props) reveal intended and unintended aspects of our identities. As Goffman put it, instead of giving information, we end up giving it off.

Social interaction depends on temporal coordination. Shared means of time reckoning (via clocks, calendars, and schedules) enable us to go to school, meet with colleagues, visit the dentist, and have dinner with our family, in concert with others. Thus, a crucial aspect of social interaction consists of our efforts to manage temporal coordination and temporal experience, what sociologist Michael G. Flaherty calls “time work.” We alter or customize our own experience of time or that of others. We are doing time work when we attempt to make the duration of an interval seem longer or shorter than it really is, when we choose to increase or decrease the frequency of a particular activity, when we modify the sequence of our conduct, when we decide the timing for an event, and when we “make” time for something, or “steal” time from someone.

The presentation of self and our time work are profoundly interwoven. Our claims to being a good person are discredited if we are late, if we take too long, if we are abrupt, and if we do something too frequently or not frequently enough. Yet the coronavirus and social distancing have disrupted calendars, have upended our finely tuned synchronization, have distorted our perception of time, and, in this process, they have created a lot of trouble for the staging of ourselves.

Online memes give us an opportunity to notice these changing mores of self and time. Simultaneously, memes express our angst and humor, but they also mark emerging efforts at adaptation, which makes them a vivid and often amusing source of data. In order to “work” and be shared, memes must touch a nerve. Memes capture the many small disasters of self-presentation and reveal the challenges of time work.

We aim to spotlight collective reflection on self and time, as embodied in memes circulating online during the period of social isolation and shutdown for the COVID-19 pandemic (from March to July, 2020). Like jokes, memes are a great medium with which to illuminate problematic aspects of the social order, decrying but also enjoying shared frustrations and insights occasioned by the pandemic’s massive disruption of everyday life. Our project was inspired by Erving Goffman’s study of photographs in magazines and newspapers (Gender Advertisements, 1979).

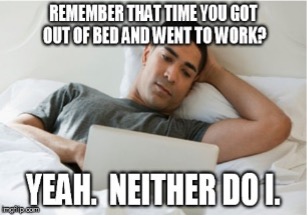

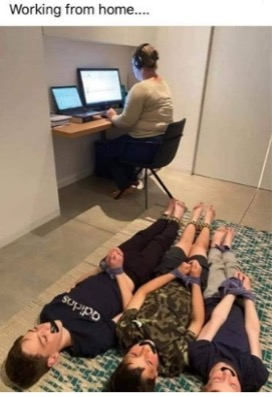

1. The tribulations of working from home have become the new normal.

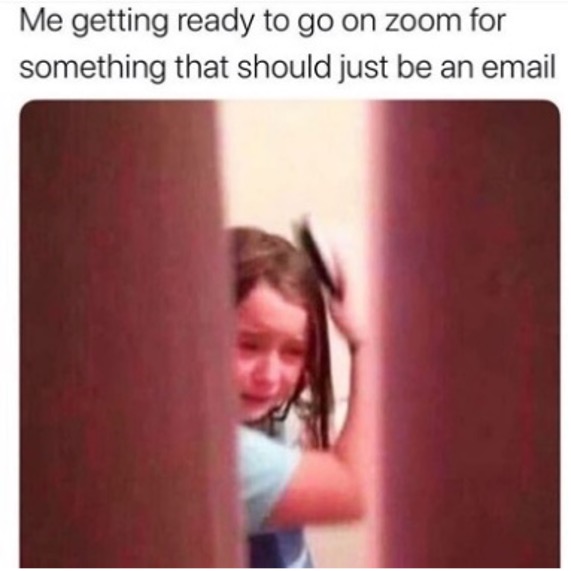

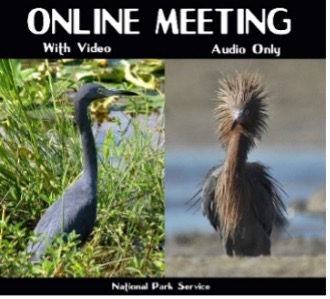

Telework is one of the strongest disruptions of sequence and timing in our enactment of self. Work and home have usually offered us separate stages and audiences for our performances. Now, the spatial separation of the two settings has disappeared, leading to temporal merging and confusion. Unexpected videoconference sightings of pets, family, or intimate clothing have become a regular source of excitement in pandemic life. Video meetings in half-formal attire and half-underwear, on kitchen tables or balconies, have become common references.

The home-workspace and equipment are not up to our usual standards. There is widespread neglect of personal upkeep. Our appearance becomes careless and unprofessional as diligence erodes and motivation evaporates. Instead of “Leaving so soon?” we imagine the Netflix sign-off says “Maybe you should take a shower and come back later.” How we look depends on whether we are communicating with others via video, audio, or email. In the absence of support staff and the usual resources, our children and pets become misbehaving and troublesome “co-workers.”

Interestingly, as more and more social interaction transpires online, our hair seems to become a growing existential concern. Our hair is a symbolic banner and often expresses tacit claims to a particular identity. Unruly hair undermines our presentation of self and threatens the validation we seek from others. Controlling our hair is an important aspect of body discipline. Crucially, hair is still visible in our online performances whereas many other facets of our physical presence have become irrelevant. Sight and sound have taken over other senses in the impoverished scenes that we e-play on screens.

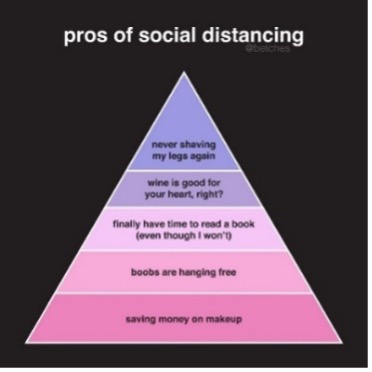

By the same token, certain aspects of our presentation of self are liberated. Suddenly, hair on female legs is celebrated, and breasts are allowed to move freely more often than before. We can wear whatever we want below the waist in Zoom meetings as long as we stay seated. The memes display celebration as well as frustration.

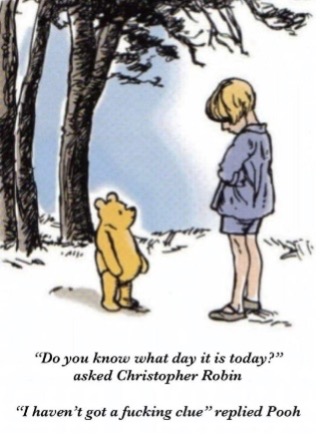

2. There is a blurring of days and weeks.

Without the rhythmic alternation from office to home, from morning to afternoon, from work to leisure, and from weekdays to weekend, we lose track of time. The days of the week have lost their conventional routines and distinctive meanings, and every day seems the same. Days and weeks merge into one long and shapeless interval that dilutes self-presentations. There are no special days that punctuate the calendar.

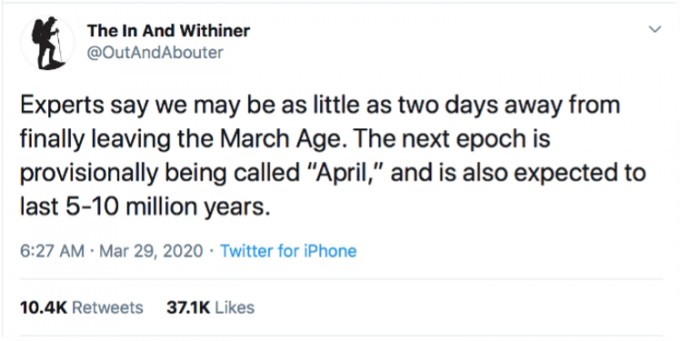

3. Time is perceived to pass slowly.

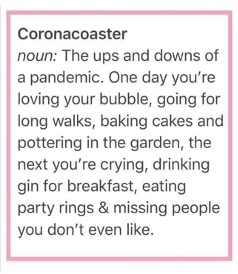

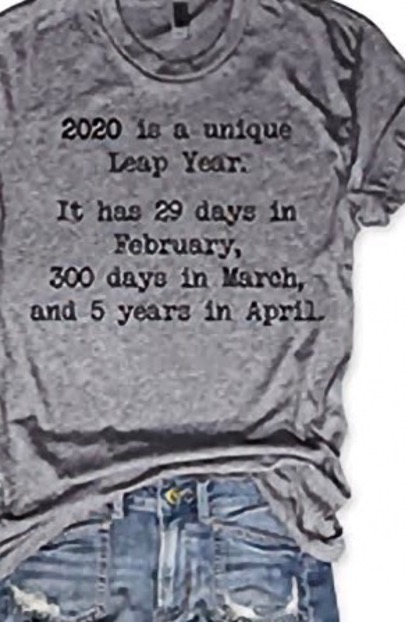

Waiting, anxiety, and boredom magnify attention to self and situation. As a result, there is a feeling of protracted duration. Thus, a great many memes represent distortion in the perceived passage of time. Each hour, day, week, and month of social distancing seems endless. Last week felt like a year; March felt like a decade or even an epoch.

With the cloistered repetition of our days, time seems stretched to gigantic proportions. Ordinarily, the social organization of time enables us to coordinate our actions with others, but this becomes nearly superfluous with social distancing and widespread unemployment. Time reckoning becomes a basis for exaggeration and joking. And those Zoom meetings? They seem to go on forever.

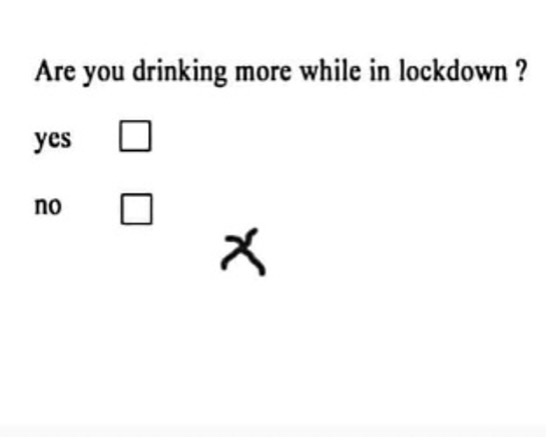

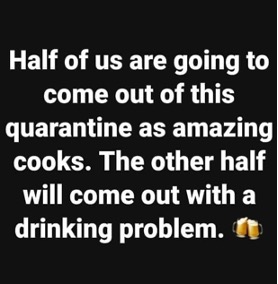

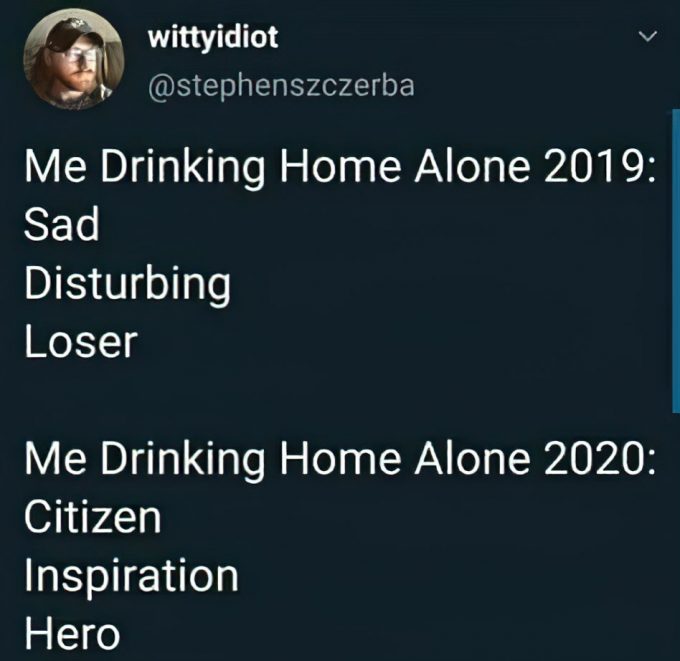

4. It would appear that, for many of us, the vicissitudes of life during the pandemic demand more diligence with self-medication.

Coffee and alcohol are two of the most widely used chemical props, stimulating, or dimming awareness, respectively. In memes, caffeine and alcohol facilitate adaptation through humor, self-expression, and weary sociability. Daily calendars are marked with beverages. On an impoverished stage, and confronting a pent-up audience, resorting to mood enhancements has intensified.

5. All of this time on our hands provokes despair in some people, creativity and contentment in others.

When all structure fails, we collapse on the furniture or floor like children overcome by lethargy and despair. Lying around has become the quintessential position in that grey area between asleep and awake, work and leisure, frontstage and backstage. Other structures that gave days direction and meaning, from horoscopes to regular outings with friends, are also lost. Not much is going on to generate interesting stories for our presentations of self. We are in sore need of quality stories and settings.

Yet there is also heroism and hedonism in un-structured time. Some love it, some hate it, some try to make the best of it. In the seventeenth century, Blaise Pascal wrote that “All of humanity’s problems stem from man’s inability to sit quietly in a room alone.” It turns out that the apocalypse is not filled with zombie terror. Instead, a ruined or stale presentation of crummy self is met with boredom and loathing on the part of an audience that is way too familiar with this performance. The elusive character of our enemy, the new coronavirus, is also partly to blame: its delayed attack, asymptomatic contagion, and lack of horrendous skin marks make it easy to underestimate from the closed confines of our impoverished home theatres.

There is a lot of variation in how we cope with the disruption occasioned by the pandemic. Indeed, for some of us, social distancing is normal social life or even something better. Self-indulgence may now be redefined as a heroic effort at containing the spread of COVID-19.

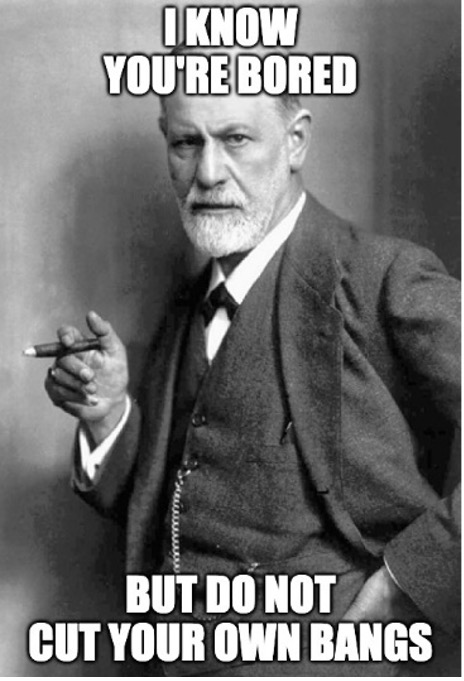

Memes point to the emergence of strange outcomes and unexpected benefits. Here, we find new and ironic forms of courage, happiness, and adaptation, as well as complaints about those who do not rise to this occasion. With nothing else to do, we exhibit extraordinary inventiveness and ludicrous inspiration. An entire kitchen is covered in glitter, and a cow’s udder on a carton of milk is pierced just so it becomes anatomically correct. Trapped in these strange circumstances, we may welcome or deplore unruly hair and unstructured time.

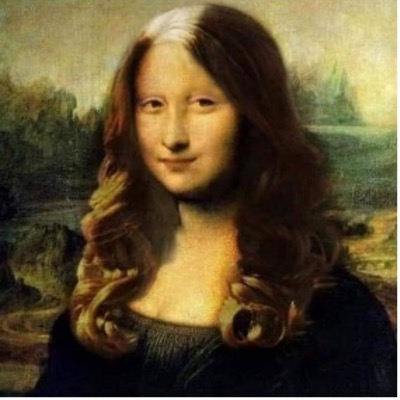

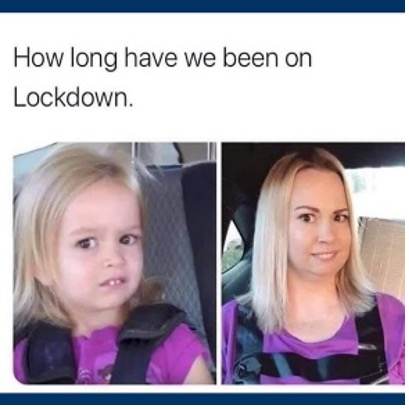

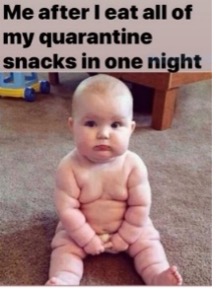

6. The deterioration of self during the long period of social distancing.

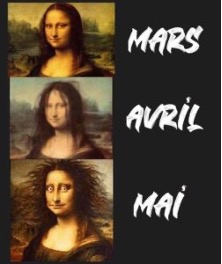

Persistent social distancing and temporal disruption take a toll on our presentation of self. The memes depict us drinking more, aging quickly, and fearfully hording toilet paper. Look, for instance, at what happens to the Mona Lisa. She was young, beautiful, and carefree. Now she is haggard and anxious – yet clinging to those few means of self-control that she has left, from nail painting to facial treatments and, of course, the stereotypical wine.

Overeating and gaining weight are common concerns. Like the cat or the baby, we may consume the food we had supposedly set aside for a possible quarantine, changing our figure in the process. We are eating our feelings and anything else we can find. We mark time and make it go away by snacking. With decreased face-to-face interactions with others, the balance of incentives has changed: There is self-indulgence instead of a finely-tuned presentation of self.

Repeatedly seeking solace in our pantries and refrigerators, we envision ourselves as annoying pests at home, constantly trying to salve our souls with something to eat. We imagine that our refrigerator grows tired of seeing us, rebuffing us reproachfully. Food adds to the gravity of the situation.

Therefore, a lot of the memes display a before-after design. We were svelte before the pandemic, but after weeks of social distancing we fear becoming considerably rounder. Our bodies could be changing in ways that reflect the newfound inertia and immobility in our lives. The humor in these memes reflects the growing tension between our new time-less and structure-less situation, and hegemonic ideals for personal self-control.

There is a great deal of voluntary and involuntary experimentation with one’s appearance. Laughable outcomes offer proof that intention matters less than skill in shaping our unruly bodies and fitting them with props. We inflict these experiments on others (including pets) as well as ourselves.

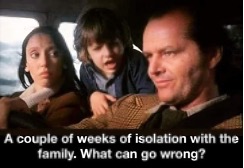

7. Memes suggest that our intimate relationships have been strained by prolonged hours of co-presence.

Our relationships entail demands on the self. Some time for privacy is intrinsic to liberty – moments of freedom from the obligations of impression management. It would appear that we miss intervals of absence or aloneness. What happens to the presentation of self when the individual confronts a nearly unchanging audience? Partners and other members of the family become inescapably and annoyingly present. One’s performance as husband or mother suffers as irritations emerge and relationships deteriorate. Memes depict the resulting discontent with gallows humor.

We have been spending a lot more time at home, alone or with our families. The other members of our household witness much the same show day after day. With few new experiences, our performances grow increasingly stale. Constantly on stage for this unavoidable and unappreciative audience, without the wherewithal to improve the script, to renew props and costumes, or to enact dress rehearsals with strangers, the presentation of self loses vibrancy and risks dullness. Tomatoes may be thrown in all directions.

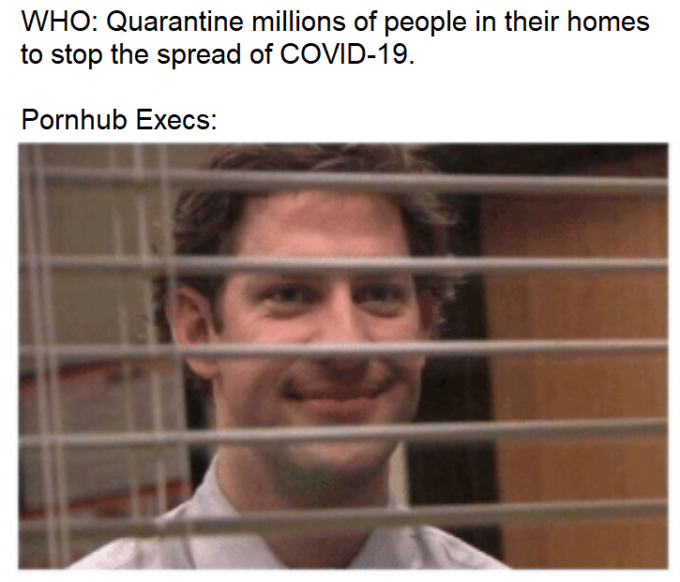

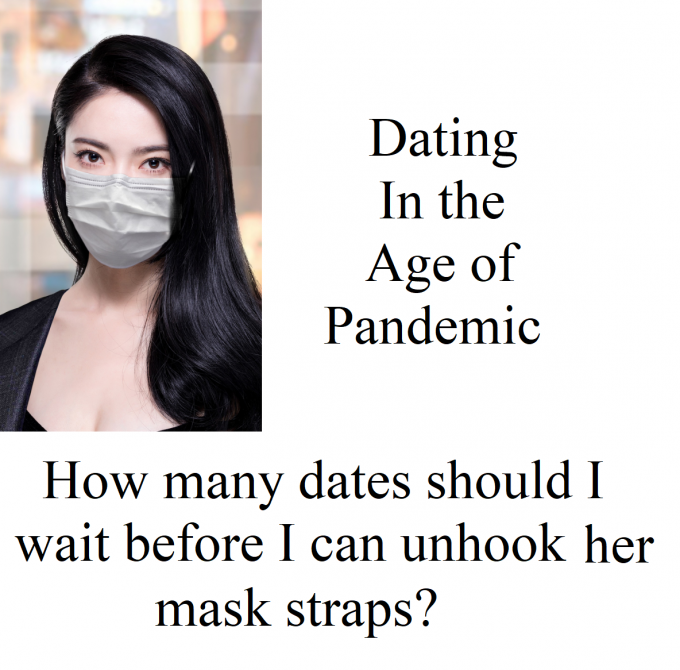

The erotic situation, a dangerous but possibly rewarding stage for self-presentation, has not fared well during the pandemic. At the outset, it seemed that a new baby boom might result from months of lockdown, but will it? Couple intimacy has been strained by continuous co-presence and overfamiliarity.

Outside of established relationships, the subtle eroticism of daily flirtation with attractive colleagues or strangers is impeded if not impossible. The pandemic diminishes opportunities for the erotic presentation of self. Will there be an upsurge in online porn and virtual encounters?

Restrictions, risks, and sheer distance make dating difficult, and change a game that had volatile rules to begin with. Optimism seems more like wishful thinking than before, and emergent dating norms are mocked in the memes.

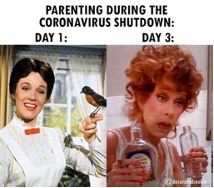

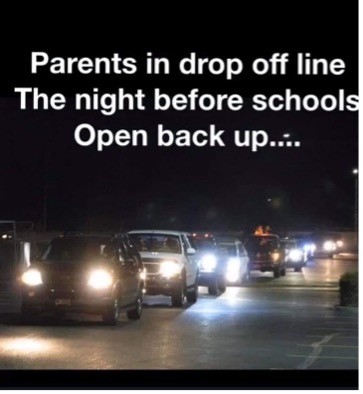

8. For many of us, our performance of intimate relationships is further complicated by the challenges of home schooling.

With comic ingenuity, memes invoke a newfound respect for the work teachers do and a decided unwillingness to add teaching at home to working from home. Judging from these memes, our ability to teach our own children is more difficult than we might have guessed before the pandemic forced it upon us.

As for kids, the most wonderful but also the most terrifying and unrewarding audience at times, our prolonged and more frequent presentations of self in front of them have brought increased risks of onstage disaster. Our usual temporal rhythm of alternating presence and absence, routine time and quality time, compartmentalized by long hours apart at schools and jobs, is no longer possible. Our homeschooling performances cast us in the role of stand-in for absent teachers, but, poorly trained and lacking requisite props, the stage is set for novel forms of bungling and fiasco.

Memes litter online platforms. It is tempting to trivialize or dismiss them, but, by turns funny or poignant, they illuminate our thoughts and feelings during this extraordinary chapter in our lives. In new ways, never envisioned by Erving Goffman, they show us that our efforts at impression management are artifacts of dramaturgy. The self is a harried and problematic performance before an audience that may be empathetic or critical. Moreover, COVID-19 has changed time reckoning and temporal experience. Under its onslaught, our standard units of time become elastic, prolonged, and unrecognizable. We feel “stuck,” unable to imagine or plan for an uncertain future, but a sense of humor is a powerful source of resilience and adaptation during these difficult days. It seems that so much has changed, but even in these unprecedented circumstances, memes confirm that the self and time are facets of social interaction.

Methods:

This article is part of the outreach component of a research project, PN-III-P4-ID-PCE-2020-1589, “The manufacture of doubt on vaccination and climate change. A comparative study of legitimacy tactics in two science-skeptical discourses”, available online at https://skepsis-project.ro/ To observe changes in self and time during the Covid-19 pandemic, we collected English-language memes circulating in multiple digital media, including Facebook, Instagram, Reddit, and WhatsApp, as well as collections of “best memes” available online. We found them by separately scrolling through postings on these platforms every day for more than sixteen weeks, and by using Google Search to locate aggregations of memes related to the Coronavirus. To date, we have assembled 111 memes, but we include only 83 of them in our manuscript in order to avoid redundancy and strike a balance between images and text. The principal criterion for inclusion was that memes must comment on social isolation in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. We excluded from consideration memes that did not invoke the pandemic as well as memes which were not visually clear or intelligible.

*For information on meme sources, please contact the authors or Contexts team.*

Recommended readings:

- Flaherty, Michael G. 2017. “Why Time Seems to Fly – or Trickle – By.” The Conversation.

- Flaherty, Michael G., Lotte Meinert, and Anne Line Dalsgård, eds. 2020. Time Work: Studies of Temporal Agency. New York: Berghahn Books.

- Goffman, Erving. 1959. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. New York: Doubleday.

- Marwick, Alice. 2013. “Memes.” Contexts 12(4):12–13.

- SNL – Saturday Night Live. 2020. “New Normal.” SNL YouTube Channel. Retrieved January 5, 2021 (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AHftFsPweMM).

Author Bios:

Michael G. Flaherty is Professor of Sociology at Eckerd College and University of South Florida. He is the author of a forthcoming book, The Cage of Days: Time and Temporal Experience in Prison (Columbia University Press, 2021).

Cosima Rughiniș is Professor of Sociology at University of Bucharest, with a research interest in the social construction of science-skeptical and science-trusting worldviews. She is now coordinating the SKEPSIS research project: https://skepsis-project.ro/

Comments 1

Beth A Rubin

April 24, 2021As usual, you are spot on!