Whitewashing the Working Class

I like nepotism!

– Donald J. Trump

Eric Trump refreshingly broke with conservative orthodoxy when he confessed the fact of his family’s privilege, effectively acknowledging that we live in an inequitable social world. “Nepotism is kind of a factor of life,” he said, in reference to his co-stewardship of the Trump Organization. To many, this might suggest a need to level artificial barriers to upward mobility. Or it could lead you to double down. “We might be here because of nepotism, but we’re not still here because of nepotism.” Oh Eric, you missed a real opportunity.

While his father ordered steaks and airstrikes from Mar-a-Lago and his sister publicly pondered what it means to be “complicit,” Eric nonetheless chipped away slightly at the monumentality of the self-made man, modern conservatism’s foundational fiction. And so did his father’s election: The Donald never renounced his racist father or the advantages his family wealth conferred. He never had to release his tax returns or perform any kind of public service. Trump, in his very person, offers a kind of neo-feudal defense of inherited privilege. Bloomberg reports, for example, that the proposed repeal of the Estate Tax “would be a bonanza” for Trump and his cabinet, the richest in history. And this in a context in which wage inequality approaches the extreme levels that prevailed prior to the Great Depression and CEOs make 335 times the pay of the average worker. How, pray tell, did his victory come to pass?

The key may have been nepotism, but of a racial sort. Whites without a college degree preferred Mr. Trump over Hillary Clinton by an astounding 39 points. To sway these new swing voters, Trump sketched a path backward to the future, with his promised return of coal and factory jobs, a Muslim ban, a beautiful border wall, a crackdown on “illegal aliens,” the return of “law and order,” the repeal of “Obamacare” and its giveaways to the underserving, tilts at multicultural global elites, and that blood-and-soil slogan, “Make America Great Again.” With all these, Trump conjured a nostalgic utopia in which men are the breadwinners and women the housewives and caretakers (consider Mike Pence’s no-dinner-with-women rule) and people of color, the help. Backwaters would become bubbling brooks, rusty machines would shudder back to life, and the Sharia-loving, cocaine-smuggling barbarians at the gates would be routed by a rejuvenated military.

It was a campaign and is now, rather unbelievably, an administration founded on restoring the “natural order of things,” in which people fundamentally know their place. Trump’s inaugural message about “American carnage” was addressed to the White dispossessed in their ruined towns. His words and actions appealed to their historical sense of entitlement and their resentment at its poor returns. “Make America White Again,” read a flyer circulating in several Virginia neighborhoods.

Trump’s campaign served as a balm for the searing wound of economic expendability. As for Hillary Clinton, rather than gathering the marginalized—Black, Brown, White—under one big Democratic tent, her campaign’s anodyne “Stronger Together” and “Fighting for Us” slogans addressed themselves to no one in particular. Her campaign was afraid to offend, while Trump happily adopted a divide-and-rule strategy worthy of any imperial administrator. The safety net that benefited the poor would be ruthlessly cut to pay for tax cuts for the rich, while Social Security and Medicare would be protected. It was a pincer movement of the angry and the affluent.

The following pieces discuss the exercise in collective self-harm that was the 2016 election. Robert Horwitz unpacks the very notion of the White working class, revealing Trump supporters as analogous to the petit bourgeois, a reliably anti-establishment and reactionary class segment. Be that as it may, Victor Chen diagnoses their very real grievances. While the sympathy extended to this group is merited, Chen notes, it is rarely offered to struggling communities of color—those are, instead, scapegoated. In this zero-sum game, Matthew W. Hughey finds that racial animus and an ideology of victimization underpin White identity. Trump, in his ravings about what a “hellhole” America has become, served as a conduit for feelings of economic and cultural dislocation. Equally important, Jason Eastman argues, is the group’s anti-institutionalism and their sense of being shafted by elites and government. Trump’s positioning as brash, swamp-draining plumber resonated, too, with rural voters, writes Katherine Cramer. They chafe against their demotion to the periphery of American life and understandably voted for a man who promised a re-elevation.

It’s anyone’s guess what will happen if economic nationalism becomes crony capitalism, when public infrastructure expenditures become tax breaks and privatization schemes, when worker empowerment becomes workplace exploitation, and when anger at Wall Street elites becomes the undoing of financial oversight. And so, Sean McElwee argues, the best way to counter Trump’s billionaire nihilism is not to chase after the lunatic fringe of the extreme right but to push for the expansion of social rights. Though the demise of unions means that solidarity is more imaginative rather than organizational, McElwee suggests that movement-building can effectively counter feelings of alienation.

– Shehzad Nadeem

- Culture Trumps Class by Robert B. Horwitz

- Hate the Game by Victor Tan Chen

- White Lives Matter? by Matthew W. Hughey

- Anti-Institutionalism and Political Rebellion by Jason Eastman

- The Grievances of the White Working Class by Katherine J. Cramer

Culture Trumps Class

by Robert B. Horwitz

Many explanations for the unexpected victory of Donald Trump in the 2016 presidential election focus on the support he received from the “White working class.” They point to several key Midwestern counties where high unemployment rates may have propelled these voters to flip from Obama in 2012 to Trump in 2016. Nationwide, exit polls showed that Trump won among Whites without a college degree by the largest margin of any candidate since 1980.

Two interconnected questions arise: Is the White working class a useful category, and, if yes, is it true that people in this demographic category gave Trump his margin of victory?

As the journalist George Packer wrote in a New Yorker article published just prior to the election, the term White working class mixes race and class—and, thus, privilege and disadvantage—in a volatile compound. In this way, the category represents an “intersectionality” of a different kind than usually punctuates sociological observation. White people are said to possess the historically rooted and cumulative advantages of domination in a conflict-riven, multi-racial society (advantages now colloquially known as White privilege). The working-class part resonates differently: It registers disadvantage or decline.

In a traditional Marxian framework, working-class designates people who sell their labor power and work for a wage—in short, class indicates a person’s relationship to the means of production. But it’s not clear that this tells us much in our complicated socio-economic world. Given that the concept of class has historically been discounted in the U.S., the appearance of the (White) working class category in public discourse is somewhat surprising. It may be because the term has been mobilized to connote downwardly mobile, poor, even pathological people (linked discursively with the ills that used to be associated with the so-called Black urban underclass). Employing a Weberian framework that combines income, educational level, and status, a roomier category of working-class captures the diminished life-chances of high-school educated, blue-collar, and perhaps especially small town and rural people whose economic fortunes have declined as their communities have experienced the decades-long shuttering of manufacturing plants and other sources of employment.

Economic decline has weakened the social institutions that previously moored social life in these communities. And it is certainly the case that some parts of the country have been damaged by globalization, outsourcing, and automation, resulting in un- and under-employment, falling incomes, poor health, drug problems, and general social disruption. Economic decline fuels and is fueled by a deep cultural disquiet. Their previous social advantages eroded, the so-called White working class is now mobilized to support political candidates who give voice to their resentment at losing economic power and cultural dominance. They see themselves squeezed from below (by undeserving “takers,” conjured as less White and including undocumented migrants) and from above (by liberal, credentialed elites who tell them what to think and create government programs that redistribute their hard-earned wages). They see their traditional values as under attack by secular humanism, the “homosexual agenda,” and political correctness. As a testament to such “values” anxieties, more than 80% of White evangelicals voted for Trump.Given all this, is the category of White working class really accurate or useful? Recall that polling showed overwhelming Trump support among White voters without college degree—a characteristic often used as a proxy for working-class. But income data complicate this picture. Voters whose yearly incomes were less than $50,000 went pretty strongly for Clinton—52% to 41%—while better off voters pulled the lever for Trump. Evangelicals across all income brackets and occupations voted heavily for Trump. This would seem to align Trump voters more closely with the demographic profile the Tea Party and the sort of very conservative, anti-establishment voters who once supported Barry Goldwater: older, White, relatively well-off, Protestant (especially evangelical), and often small-business owners.

In short, the Trump voters identified as White working class do not clearly constitute a class in the occupational sense, nor do they constitute a class if we use income as a key measure. While disenfranchised Whites in key swing states helped give Trump his electoral college margin, pinning Trump’s victory on the White working class may obscure more than it illuminates. The vast bulk of Trump voters remains a cultural formation characterized by anti-establishment, anti-elite, and quasi-authoritarian attitudes—these are the “anti-establishment conservatives” we have seen before.

Lewis Hine, 1920. Work Progress Administration 69-RH-4L-2. Public Domain

Hate the Game

by Victor Tan Chen

After the November election, national media attention turned to the White working class. Many people argued Donald Trump’s victory had hinged on this demographic’s failure to turn out for Hillary Clinton.

Scholarly interest had already been piqued by the 2015 publication of a paper by two economists, Anne Case and Angus Deaton. They found that White Americans—though not African Americans or Hispanics—experienced dramatic spikes in deaths due to suicide, drug poisonings, and chronic liver diseases between 1999 and 2013. Individuals without college degrees (one oft-used definition of the “working class”) were hit hardest by these so-called deaths of despair. A year later, this and similar studies were in the headlines again, as possible explanations for Donald Trump’s victory in November. For example, a much-discussed study by Shannon Monnat found that Trump did especially well among voters in counties with the highest rates of drug, alcohol, and suicide mortality.

In my book on unemployed autoworkers and in op-eds written before and after the election, I have written sympathetically about the White working class and its declining fortunes. While I emphasize the broader economic and social trends affecting this group, I’ve also come across many thoughtful critics who see my approach as reductive. The sad state of White America gets the media spotlight, they point out, even though people of color comprise a disproportionately large—and growing—segment of the working class.

Another criticism is that mainstream commentary tends to pin working-class Whites’ plight on larger economic and political forces without extending the same analytical generosity to Blacks, who were hit earlier and harder by globalization, automation, and rightist revanchist politics. When the national conversation was focused on rising rates of crime, the crack epidemic, and welfare reform in the 1980s and ’90s, urban African Americans were yet again painted as lazy, irresponsible, and prone to criminality—that is, culturally and morally (and even genetically) flawed. Yet fast forward to 2016, and the media was calling the largely White opioid epidemic a public health crisis, the breakdown of “heartland” communities an obvious outgrowth of automation and the offshoring of high-paying factory jobs.

It’s good that more Americans are willing to entertain structural explanations for the economic woes of certain groups. But we should apply the same logic to other demographics, too. After all, the way we talk about the problems besetting the working class—and which working class we choose to talk about—has important political consequences. As my own research underscores, what limited assistance America provides to its unemployed is heavily weighted toward manufacturing workers who lost their job due to foreign competition. Whites, more likely to be employed in the manufacturing sector, can access generous retraining opportunities and income support from the federal government’s Trade Adjustment Assistance program. Meanwhile, the “new” working class—service-sector workers who are disproportionately women and racial minorities—are left out.Perhaps the most troubling critique of the working-class Whites commentary cottage industry is that it excuses the virulent racism in this group. As I noted in a recent essay, the working-class identity that White men adopted in the nineteenth century to bring together long-warring European ethnic groups was built upon racist and sexist ideologies, and this mindset has persisted. Some surveys suggest that overall voter support for Trump was associated most strongly with racial anxieties, as opposed to economic hardship per se. This shouldn’t be surprising, given that Trump’s winning coalition brought together affluent voters and less educated voters.

It’s crucial to keep examining the role racism and misogyny play in our politics, and it’s possible to do that while also recognizing the real suffering in less advantaged communities. As I describe in my book, the feeling that they are “losers” in today’s economic game wounds the working class—White and non-White alike—and makes them lash out. Without labor unions or other institutions to channel that anger toward an unfair system, too often what results is a bitterness toward scapegoated groups or a despair that descends into self-harm. Understanding the social structure that constrains the White working class does not mean being soft on the political leaders who have so successfully exploited this group, cynically feeding the cultural anxieties of working-class Whites while shaping economic policy to favor themselves. Challenging them will require hardheaded organizing, and it is important that we are precise about the target. To put it simply: don’t hate the player, hate the game.

White Lives Matter?

by Matthew W. Hughey

Who is the “White working class”? The moniker, representing an ostensibly extant and easy-to-recognize demographic, often evokes the image of an economically disaffected, modestly educated, racially prejudiced, and gender-traditional figure who stalks either rural farmlands or urban centers of the American rustbelt. He sports blue collars and wears red politics on his sleeves.

While evidence proves part of this story true, the group is far from a monolith. For instance, while approximately 90 million White adults do not hold college degrees, nearly half have some college education and/or an associate’s degree. They are not the Bible-thumping, finger-waving culture warriors some expect (they are no more likely to attend church or marry than their low- or high-class counterparts). And relatively few hold actual “blue-collar” trade professions (most are employed in managerial or service industries). But one particular variable does jump out, at least for my research interests: White lives matter. That is, according to a 2016 American National Election Studies survey, about 36 million of that 90 million total report that their Whiteness is “very” or “extremely” important to their identity.In examining how Whites make meaning of themselves, the sociologist W. E. B. Du Bois asked in 1920, “…why will this Soul of White Folk—this modern Prometheus—hang bound by his own binding, tethered by a fable of the past?” In this vein, what is it about Whiteness that gathered and compelled an otherwise heterogeneous mass of working-class Whites into such uniformity on Election Day 2016 (67% of Whites without a college degree voted for the Republican nominee—a 14% jump from 2012)?

Much ink has been spilled in pondering Trump’s supposed “economic populism” and the power of political ideologies to magnetize the White working class. But what measures of White attitudes fail to acknowledge is that racism against people of color correlated much more closely with support for Trump than did attitudes about economic dissatisfaction, even after controlling for political partisanship and political ideology. It’s not a matter of whether race trumps (pardon the pun) either economics or political ideology (or vice versa), but how these voters interpret the world through the lens of Whiteness.

My own research on all-White groups, as laid out in White Bound: Nationalists, Antiracists, and the Shared Meanings of Race, provides a nuanced analysis of these larger demographic trends. In considering the full span of Whiteness—from White nationalist and White antiracist ideologues in the mid-Atlantic U.S. to Deep South, all-White young professional groups and college alumni chapters and the all-White civic fraternal orders and patriotic lineage societies in New England—I’ve found that inter-subjectively shared notions of Whiteness create rather solid pathways and patterns of action and order.

Across diverse locales and settings, there are striking similarities among the White working class. They collectively attempt to reclaim, paraphrasing the historian Stephanie Coontz, a Whiteness that never was (consider the appeal of “Make America Great Again”) and can never be (seen in the Faustian bargain in which Whites chase after a kind of superiority and elite social position that is anything but attainable).

In the former, many Whites believe they have been cheated out of a kind of ontological birthright; an inheritance of domination qua social greatness now stolen by people of color. These worldviews manifest in the retention of workplace slurs and epithets, disdain for policies like affirmative action, and the belief that any gains by people of color exist in zero-sum relation to White comfort and security.

In the latter, Whites chase dimensions of an ideal White identity (what I have called “hegemonic Whiteness”). These ideals are so lofty they are unachievable. Consequently, White formations do not move into or out of crisis, they are constituted by crisis—of attainment. The grammatical shift is subtle and important. Whether attempting to stoically overcome their perceived racial victimization, rationally supporting racial hierarchies via irrational theories of cultural or biological essentialism, or advocating a nouveau White (wo)man’s burden that valorizes their own paternalism over people of color while expecting non-Whites’ contented gratitude, the dimensions of “who” a competent and good working-class White person should be are fundamentally unattainable. This crisis manifests in the constant scapegoating of people of color, immigrants, and their intersection; working-class Whites need a reason for failing to reach the heights they believe they should occupy.

White fragility is a direct result of the extraordinary claims of past and future superiority made on behalf of Whites; the “crisis” is constitutive of the subjects that seek a remedy for their perceived predicament.

So who is the “White working class”? Better yet, when is the White working class? We can better answer by recognizing that even when motivations seem purely “economic” or “political” they fundamentally trace back to White temporality—they share the chase to “reclaim” and attain how Whiteness was and how it needs to be. A sense of racial crisis neither bubbles up nor appears sporadically in the form of a social movement “backlash” or in unexpected election results. The crisis of Whiteness transcends time. Whites are always, as Du Bois put it, hanging by their “own binding.”

Anti-Institutionalism and Political Rebellion

by Jason Eastman

In the late 1970s, a generational trend of flattening socio-economic inequalities started to reverse. That is, opportunities for the working class decreased, creating what we see today in the U.S.: irrational chasms of income and wealth not seen since the Gilded Age. Yet as these class inequalities grew, research on socio-economic disparities waned. Social scientists came to focus more on race, ethnicity, gender and LGBTQ+ inequalities. However, recent political shifts abruptly made the White working-class politically relevant again, and social scientists are relying heavily on diversity frames to explain this electoral realignment via the anti-minority, anti-women, anti-immigrant, anti-LGTBQ+, and anti-Muslim sentiments at play in our newer world dis-order.

Doubtlessly, the political resurgence entails rejections of others, yet my unique experiences lead me to believe there is more at work. I grew up in Northern Appalachia, playing on the rusted oil and coal extraction equipment abandoned by generations before me. I spent over a decade with southern rock musicians as I researched my book. And more recent studies have required that I immerse myself in Interstate truck stops, Myrtle Beach biker bars, and now a farm on the banks of the Allegheny River. I see an “anti-institutionalism” at the heart of contemporary working-class politics, and it entails rebellion from just about every social institution the White working-class has watched crumble around them.

The classic “government is the problem” ideology is the easiest place to see anti-institutional politics, but now this sentiment encompasses even state-affiliated institutions once held sacred by the White working-class. Blue-collar men once took pride in military service, but seeing disproportionate fighting and dying in unpopular wars and watching veterans suffer without healthcare via the VA or Obamacare means there are now more POW-MIA banners dotting the rural landscape than there are American flags. The country’s highest offices are held by draft dodgers who question the service of heroes. Law enforcement was once seen as a pillar of community; today, bumper stickers and porch signs reading “We Don’t Call 9-1-1” have spread across flyover country. These imply that the White working-class has more trust in their own vigilante justice than the protective service of the police or the courts (supreme or otherwise). Of course, in my studies, none have ever said they’re against the more stringent policing of minorities.

The name “working-class” doesn’t even fit anymore. This group’s financial well-being has been decimated by a generation of offshoring. Consequently, work is no longer central to their identity. There was always an anti-authority streak among blue-collar laborers, but it has evolved into full rebellion and a rejection of the trappings of an American Dream that’s no longer available. Can’t have it? Didn’t want it anyway. When I was a kid, the shop-talk around me was about hard-earned pensions reflecting a lifetime of work, dedication, and devotion to an employer or a craft. Today, I hear talk of “hustling,” carving out a living at the margins of an underground economy, and “working the system,” perhaps by exploiting tax codes or bankruptcy laws. Those who work harder and harder for less and less are derided as “stupid.”Similarly, stranded in underfunded primary schools and priced out of higher education, the White working-class rejects “book learning”—it’s a waste of time when, in their “real world,” people are forced to fend for themselves, to do what it takes to exist with very limited resources (salvaging scrap metal, selling prescription drugs, hunting and fishing out-of-season, etc.). According to many White working-class voters, politicians with academic credentials are untrustworthy bearers of useless knowledge—these career politicians are thought “obviously” dirty and stained simply by having risen through a system that is more corrupt than meritocratic.

White, working-class “values voters” have lost their faith in other institutions once depicted as the cornerstones of community. More and more of the poor live unmarried, no longer seeing their lives through familial roles, but sometimes seeing partnership and parenthood as undue burdens. A generation of televangelism and unanswered prayers pushed many not only to leave the church, but also to chastise “the suckers” who still show up on Sunday. Sex scandals and moral breaches are unlikely to derail the political ambitions of those catering to this new amoral majority.

It’s true that the White working-class is far from progressive on issues around race, gender, and LGBTQ+ rights; a good bit of the resurgence in their political participation and support for “outsider candidates” can be explained along those lines. But a large proportion of the White working-class does not explicitly define their political selves along the lines of race, religion, and sexual identity. In fact, if there is a political identity at work here, it’s a rebel or outlaw identity challenging the system. Ironically, these days it’s because of the regional (rather than proportional) apportionment of representative seats and electoral votes that these outlaws have the structural opportunity to exercise power at all.

The Grievances of the White Working Class

by Katherine J. Cramer

Listening to Donald Trump in the first months of his presidency, one gets the impression that the system is rigged against him. This might seem a little strange for the leader of the free world, but feeling like you’ve always got losing odds is a perspective many of his White working-class supporters can relate to. Candidate Trump claimed the Republican Party establishment and the media were out to get him, that the first debate’s questions were hostile and his microphone was faulty, that he was an aggrieved warrior fighting an uphill battle for the “real America.”

Trump is now in charge of the “rigged” system, and he’s learning that it’s more difficult to strike the pose of an aggrieved underdog when you’re the President of the United States. Still, by complaining about “fake news” and speaking directly to his base via Twitter, he is telling the public that he is not getting his fair share of attention and respect. In this way, the White working class can still relate to him.

Since 2007, I have been inviting myself into conversations among White working-class voters in small towns and rural communities in Wisconsin. In these visits, I have heard an intense and pervasive resentment toward urban areas. Many told me that they always got the short end of the stick. They feel ignored by those in power, especially those in government. As one woman put it: “[W]e totally live differently than they city people live. So they need to think more rural instead of all this city area.”

They also think they’re being shorted their fair share of taxpayer dollars. I heard this often with respect to education, for example. A woman meeting up with a weekly brunch bunch in northwest Wisconsin said something about resource allocation back in 2007 that I have heard variously stated by other people since. “The money is collected here, it is sent to Madison, and it is dispersed to Milwaukee and Madison [our two main metro areas] primarily so our return on what we spend is very little, you know?” In their eyes, they pay high taxes, but that money gets spent in the cities, not on people like them or in communities like theirs. The actual allocation of state and federal dollars shows that people in rural areas in Wisconsin do not get less than their fair share, but unemployment and poverty are higher and median household income is lower, feeding their perception of fewer resources.

And perhaps most importantly, they feel they don’t get their due respect. Rural dwellers perceive that urban elites, from policy makers to people in the news industry, just do not understand rural people—their way of life, their values, their daily concerns. Another woman, at a weekly church basement gathering in a tiny town, told me that decision-makers in Madison and Milwaukee “don’t understand how rural people live and what we deal with and our problems.”

In my decade of observation, there is an enduring sense that White folks outside urban centers are hard-working Americans, playing by the rules but unable to get ahead because the system is rigged against them. They think that communities like theirs are locked in a dying economy, regardless of how hard they try. They believe White folks get less respect than they deserve these days, and that others—racial and ethnic minorities, urban elites, public employees, neighbors on disability—are taking far more than they deserve.

This sense of grievance is powerful because there are so many identities wrapped up in it. There is the rural versus urban divide. There is racism. There is class identity and partisan identity, too.

I joined a summer 2012 dice game with a group of men, both retired and currently working, who meet up before the workday in a small town in a rural and low-income county in west-central Wisconsin. My appearance—I’d driven up from Madison—prompted yet another conversation about taxation when I told one man that it wouldn’t do for me to join the game and take all their quarters. “That [is] a lesson to remember,” he said. “Madison sucks it all away.” Another man speculated that cities south of Highway 21, which they refer to as the Mason-Dixon Line, were funding schools with property taxes from northern towns like theirs. The first man took it up, saying, “if they would bring us their school district money back, we wouldn’t have to raise taxes” and marveling, “We keep our schools up and they [Milwaukee] let theirs fall apart and we pay them more.” Later, his compatriot was more explicit: “The politics down there . . . they saw all this wooded land and of course that’s God’s country and why are all these people able to own that and they’re paying nothing for property tax on it, you know.” The folks in the cities, these men seemed to say, are jealous and resentful, as well as careless, clueless, and mean.

On the surface Donald Trump has little in common with the men around this table. He’s wealthy. He’s urban. He has gotten decades of media attention. But nevertheless, his aggrieved stance resonates with many White working-class voters.

Drawing social class boundaries is a difficult task. We normally do this by pointing to socioeconomic characteristics. But we can also do it by asking people to slot themselves according to the class categories we create. What we are learning in the Trump era is that we must pay attention to the nature of voters’ grievances and where they think they stand in the pecking order of society. By attending to perceived and subjective characteristics, we can better understand class and the appeal of Trumpism in modern America.Racism Hurts Democrats in 2016

by Sean McElwee

Why do low- and moderate-income Whites support politicians who offer nothing in material benefit for them? It’s possibly the greatest mystery in American politics. Lyndon Johnson once said, “if you can convince the lowest white man he’s better than the best colored man, he won’t notice you’re picking his pocket.” My analysis suggests he’s right: among working-class and college-educated Whites, evoking race can absolutely reduce support for policies that would materially benefit them.

Here, I examine the battery of questions asked on the 2016 Cooperative Congressional Election Studies (CCES) survey, which asks respondents whether they “strongly agree,” “somewhat agree” “neither agree nor disagree,” “somewhat disagree” or “strongly disagree” with these statements:

- I am angry that racism exists.

- White people in the U.S. have certain advantages because of the color of their skin.

- Racial problems in the U.S. are rare, isolated situations.

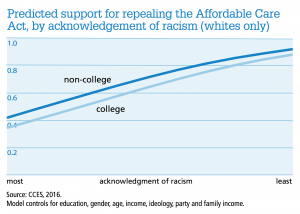

I used these questions to create an index, with 0 signifying the highest acknowledgement of racism and 1 the lowest (the first two questions signal acknowledgement, the third a rejection— they were recoded to go in the same direction). The mean score for White respondents was .33. White Democrats’ mean was .18, with .37 for White Independents and .44 for White Republicans. Racism is obviously multi-faceted, but for the purposes of this essay, I’ll refer to the index by the short-hand of racism.

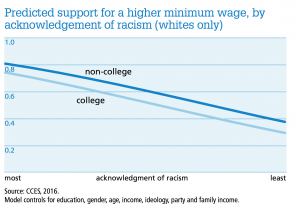

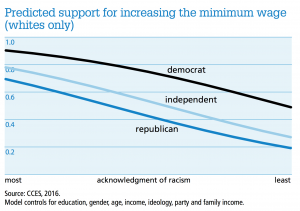

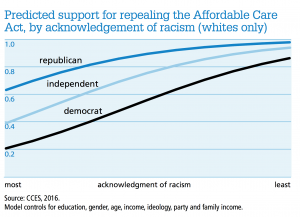

Next I explored support for repealing the Affordable Care Act using a logistic regression that controls for race, education, family income, age, ideology, party, and gender. As the chart shows, among both non-college and college-educated Whites, support for repeal is inversely proportional to the acknowledgement of racism index—that is, those who most believe that racism is a persistent problem are least supportive of an ACA repeal. I also explored a more directly redistributive policy: raising the federal minimum wage. As the chart shows, a higher acknowledgement of racism predicts a higher support for a minimum wage hike. The same patterns emerge when splitting up White voters by party. This suggests that, as research has long suggested, racism peels off support for economically progressive policies.

So what constitutes a winning coalition for Democrats? While it’s broadly true that non-college Whites are less progressive on racial issues than college-educated Whites, Democrats must still make inroads with a large swath of non-college, working-class White voters. Using higher scores on acknowledgement index as a proxy (albeit, imperfect) for racism, I divided the electorate into five groups: people of color (24%), college-educated Whites with above- (10%) and below-average racism (15%), and working-class Whites with above- (27%) and below-average racism (25%) (percentages add to 101 percent due to rounding).

In the 2016 presidential election, Democrat Hillary Clinton won 58% of working-class Whites with below-average racism and 76% of college-educated Whites with below-average racism. This suggests that Democrats could still win over more working-class Whites without sacrificing their commitment to racial equity. Republican Donald Trump won 78% of college-educated Whites with high levels of racism and 83% of working-class Whites with above-average racism. The backbone of Trump’s coalition was, indeed, working-class Whites with above-average levels of racism (48% of his voters). Compared to Mitt Romney’s performance in the 2012 election, Trump performed better with this group, taking 83% compared to Romney’s 75%. Trump also improved on Romney among working-class Whites with below-average racism, taking 36% of that group to Romney’s 31%.Clinton’s coalition may be somewhat surprising: at 30%, working-class Whites with below-average levels of racism made up a larger share than college-educated Whites with below-average levels of racism (23%). People of color were an impressive 38% of her voters, followed by non-college educated Whites (36%) and college-educated Whites (26%).

With these numbers in front of us, the task of the left is to first emphasize that all working-class people benefit from progressive policies. Progressives must begin creating spaces for cross-racial, working-class organizing. Unions can provide a model. In addition, the debate about whether Democrats should aim to win college-educated Whites or “working-class” Whites is an imprecise framing of the problem. Democrats should aim to win over all Whites committed to race, gender, and economic equity as they work to mobilize young people and people of color (many of whom voted third-party or sat out the 2016 election). In addition, progressives should actively work to meld economic progressivism with a commitment to racial equity, gender equality, and LGBT rights—there are precedents for such a movement, but they show it won’t emerge without progressive investment. Without an explicit commitment to racial equity, economic populism might easily slide into Bannonism; at the same time, a too-narrow focus on identity will leave millions behind.

Comments 1

John Beech

August 11, 2017Katherine,

As a white working class man who has climbed the economic ladder by dint of ingenuity and hard work, I find your condescension toward the President (and myself for supporting him) something of an irritant. Is it any wonder there's resentment in small town America when those in large cities (e.g. their political representatives) are overwhelmingly powerful in comparison and utterly indifferent to those of 'we the people' living in small towns and rural America? Would we today, for example, have electricity if not for an act to electrify the nation dating back to 1936? I wonder because today we don't have such basics as high speed internet access - and there's zero indication big-city politicians know or care about our issues. Thus, President Trump may be a joke to you, and he may be portrayed as a clown by many halfwits in the press, but at least he pays lip service to us. As a consequence, and respectfully, please walk a mile in our shoes before presuming to lecture us.