Image by Syaibatul Hamdi from Pixabay

COVID-19 and the Future of Society

The coronavirus epidemic is a classic “right now” crisis. A new disease has entered the human population and is quickly claiming hundreds of thousands of lives. Hospitals around the world are at their limits. Healthcare providers are going far beyond their professional obligation to support the sick and dying. The coronavirus has forced many of us to go home and “shelter,” which has resulted in sudden, and very large, surges of unemployment.

Even though COVID-19 has created an extended emergency, it will end. Shops will open and the streets will soon be filled with pedestrians. What that means is that we will all have to learn to live with the risk posed by the coronavirus, just as people needed to persist in the times of polio and other contagions. Many of our readers are scholars and teachers who are now planning to resume their duties this coming Fall. Already, governors in the U.S. are considering opening businesses and allowing more travel and commerce.

What will such a world look like? The essays in this final installment of Contexts Magazine’s online coverage of the COVID-19 pandemic explore the future. Padmanabhan Seshaiyer and Connie L. McNeely offer an overview in terms of development goals. They ask how coronavirus will change the goals that international institutions develop. Stephen F. Steel asks us to use basic sociological ideas to interpret the epidemic and its consequences.

Angran Li and Allen Hyde provide us insights into how health insurance access will still be an issue moving forward. Their findings support a push toward universal healthcare to deal with future waves of outbreaks. Whitney Pirtle addresses how racial capitalism is a global problem and will continue to impact virus outbreaks and healthcare. “A Crowdsourced Sociology of COVID-19” is an interesting piece written by a team of sociologists who lay out future research trajectories for researchers. In a provocative commentary, Jacob Thomas asks how the epidemic might create opportunities for the improvement of society. For example, he asks if this crisis will allow us to develop non-geographically based networks better than we have before.

In concluding this series of commentaries, we would like to offer a note of optimism from the editorial team at ContextsMagazine. Sociology is a discipline that often focuses on challenges and barriers. And for good reason – without critique, progress is not possible. But once critique is rendered, movement is the next step. When a crisis begins, it is all too easy to retreat into a monotonous cycle of pessimism. The news, every day, brings us examples of bad decisions and poor behavior. Instead, we should take stock of the marvelous thing that is humanity. We are creative, compassionate, and brilliant. We can see this in our healthcare workers, frontline workers, first responders, teachers, medical researchers and all the people trying to make a living in this tough time. It’s an uphill road, but we can make it to the top.

Be well!

– Rashawn Ray and Fabio Rojas

-

- “The Impact of COVID-19 on the UN Sustainable Development Goals” by Padmanabhan Seshaiyer and Connie L. McNeely

- “Sociological Imagination versus COVID19: ‘A Little Soc Can Go A Long Way’” by Stephen F. Steele

- “A Slow Start on an Urgent Crisis: How Lack of Health Insurance Helps Explain Deficiencies in Coronavirus Testing in U.S. States” by Angran Li and Allen Hyde

- “Global Racial Capitalism as a Fundamental Cause of COVID-19 Disease Disparities in the World” by Whitney Pirtle

- “A Crowdsourced Sociology of COVID-19” by Jenny L. Davis, Erika Altmann, Naomi Barnes, James Chouinard, D’Lane R. Compton, Amber R. Crowell, Peta S. Cook, Simon Copland, Laura Dunstan, Katharine Gary, Anna Jobin, Christopher Julien, Helen Keane, Gemma Killen, Hùòng Lê, Jennifer Lê, Stewart David Lockie, Ben Lyall, Maitahitui, Alexia Maddox, Annetta Mallon, Bianca Manago, Lizzie Maughan, Daniel Morrison, Chantrey J. Murphy, Mikayla Novak, Rebecca Olson, Elaine Pratley, Hedda Ransan-Cooper, Timothy Recuber, Deana Rohlinger, Judy Rose, Suzanne Schrijnder, Naomi Smith, Holly Thorpe, Francesca Tripodi, Samantha Vilkins, Matthew Wade, Apryl Williams, Nathan Wiltshire, and Mark Wong

- “How COVID-19 Can Inspire Us To Change Society for the Better in the Long Run (If We Take It Seriously)” by Jacob Thomas

The Impact of COVID-19 on the UN Sustainable Development Goals by Padmanabhan Seshaiyer and Connie L. McNeely

The United Nations adopted 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2015, providing a shared vision for tackling some of the most enduring global challenges. Notably, the third goal — ensuring healthy lives and promoting well-being for all — refers to strengthening the capacity of all countries, particularly developing countries, for early warning, risk reduction, and management of national and international health risks. Today’s novel Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) crisis has added dimensions of complexity to this problem.

While COVID-19 can initially appear an equal opportunity disease, the impact will be especially dire in some contexts and groups. Poverty and disease interact with and reinforce each other, becoming particularly acute when considering that over 736 million people in the world live in extreme poverty, disproportionately suffering from disease and ill health (SDG1: No Poverty). COVID-19 is expected to create and exacerbate food-insecurity among millions of poor and low-income groups. There will be a great need for networks of food sources and quick action by policymakers to maximize public nutrition provisions to prevent increased hunger among vulnerable populations (SDG2: Zero Hunger). With lack of access to medical resources and necessities such as water and effective sanitation, it will be challenging to promote the health and wellbeing across groups and contexts. Also, it is well known that time between vaccine development, testing, and production can be quite long (SDG3: Good Health and Well-Being). With worldwide closing of educational facilities, the need to create inclusive opportunities is apparent. This is also an opportunity to engage students in cross-disciplinary learning about the virus through a variety of approaches including inquiry-based, problem- based, experiential-based, and much more. Sociology perspectives can also provide theoretical and methodological foundations for connecting frameworks and integrating analysis for public health and wellbeing (SDG4: Quality Education). Current trends show COVID-19 infecting men and women in about equal numbers. However, with the majority of careworkers in the world being women and also with expanded responsibilities typically falling on them for additional childcare due to mass school closures, COVID-19 is expected to impact women more than men (SDG5: Gender Equality). People who cannot afford such conveniences as the recommended hand sanitizers to ward off transmission do not have many options beyond basic soap and water. For vast numbers globally without access to clean water, the situation could get much worse (SDG6: Clean Water and Sanitation). The COVID-19 situation has highlighted the need to have long-term energy facilities to bolster security of supply. For example, lack of solar panel shipments from China has created delivery bottlenecks and could delay many projects impacting renewable energy provision (SDG7: Affordable and Clean Energy). COVID-19 represents a significant threat to the sustainability of businesses and jobs. While “social distancing” has been proposed to avoid infection, this has prompted some people to telework, also impacting other occupations. Related infrastructural effects will be impacted by absenteeism within sectors and levels of specific expertise required to sustain them. Initial assessments indicate the loss of as many as 25 million jobs worldwide resulting from COVID- 19, pushing millions of people into unemployment, underemployment, and working poverty. (SDG8: Decent Work and Economic Growth; SDG9: Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure). COVID-19 is expected to affect social, economic, and environmental aspects of sustainable development. Social determinants of health and resulting disparities are of particular concern. Policy attention must be given to increasing the ability to be tested freely, access to affordable face masks, basic utilities, guaranteed health benefits, and paid emergency leave. Also, if not universal, policies can fail to support disadvantaged and vulnerable populations (SDG10: Reduce Inequality). With more than half the global population living in cities, there is great potential to enhance pandemic risk. Moreover, pandemics often emerge from the edge of cities, with viral outbreaks transmitted via urban communities and transportation corridors at the outskirts before spreading to the interiors. Currently there is no formal city-preparedness pandemic index plan or policy to respond to outbreaks such as COVID-19 (SDG11: Sustainable Cities and Communities). With school and business closings, demands for media consumption is bound to increase. Moreover, consumers are being forced to dramatically change their purchasing behaviors. Marked changes are occurring in proactive buying and reactive health management, with consumers in COVID-19 impacted areas stocking up on health-safety products, leading to continuous out-of-stock supplies and logistical problems in production and distribution systems (SDG12: Responsible Consumption and Production). Impacts on climate already are apparent — dramatic drops in airborne nitrogen dioxide pollution due to China’s lockdown policy, and other parts of the world also seeing lowered emissions. Working remotely and teleconferencing are reducing traffic and related pollution. Such behavior changes help control carbon emissions and progress in decarbonization (SDG13: Climate Action). Deforestation and deterioration of coastal waters adversely affect ecosystems and biodiversity. For example, marine plastic pollution, coming from various sources — fisheries, aquaculture, and illegal dumping — is a major environmental problem. Research indicating that COVID-19 virus lives two times longer on plastic than cardboard may prompt use and disposal behavioral changes, even using less in households, which could ultimately impact marine plastic pollution. Also, research indicates that humanity’s destruction of biodiversity creates natural conditions for viruses like COVID-19 to arise (SDG14: Life Below Water; SDG15: Life on Land). With COVID-19 creating an economic crisis, increased homelessness and hunger are expected. Related anxiety has ironically increased gun sales in countries like the U.S., where buyers believe violent acts and riots will erupt. Such behavior is not uncommon during crises in any country and governments should be prepared for associated civil disturbances (SDG16: Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions). With a shared goal and vision for avoiding the spread of COVID-19, inclusive partnerships are needed at global, regional, national, and local levels. Policies must address a range of issues, including international and national cooperation and coordination, cross-sectoral exchanges and interfaces, and governmental and nongovernmental relations. Learning how other countries are controlling the pandemic through global partnerships, mobilizing funding and long-term investments, and creating government stimulus efforts can help fight the COVID-19 crisis as a united front (SDG 17: Partnerships).

Padmanabhan Seshaiyer is a Professor of Mathematical Sciences at George Mason University and Connie L. McNeelyis a Professor of Public Policy at George Mason University.

Sociological Imagination versus COVID19: “A Little Soc Can Go A Long Way” by Stephen F. Steele

“OK, nice stuff, but how can you use it?” How can sociology provide practical answers for a public trying to understand a crisis? Sometimes we struggle with an answer, but the global tragedy of the Coronavirus set the stage for some straightforward answers. Just about anyone who has had an a little sociology under their belt could add some helpful guidance. Even the most basic sociological tool kit plus a little sociological imagination (with due respect to C. Wright Mills) can be… and, in fact, has been the tip of the spear in the war on COVID19. Let’s just review a few of these uses of sociological sense.

Sociological perspective. The virus and its natural progression may have done far more than most lectures could in revealing the usefulness of our perspective. When one realizes that sociology is – at its core – the science of human interaction… voila! Whether we’re talking micro, meso or macro interactions these last weeks have unleashed a frenzy of social science ideas and tools in understanding how humans act with each other. Fundamentally: How is this virus transferred you say? Through human interaction! Now you’re on our turf. Then, we’re off and running to not only conceptualize the problem but also offer some solutions. Let’s drill down a little.

Interaction rituals. What are the patterns of person-to-person interaction? This leads us to everything from “don’t shake hands,” or “no hugging” to “No, you can’t kiss grandma!” And then, patterns of proximity… “Stay six feet apart!” Though this may not be what Bogardus had in mind, we’re really using the social distance concept in real physical terms. Of course, when you add the concepts of culture and subculture we remind virus fighters that this interaction thing isn’t one size fits all.

Besides, we have become more aware that Goffman reminded us that interaction is a crapshoot. There’s no guarantee grasping Uncle Billy’s unwashed hand will lead to a trip to the ICU. No. It’s a probability game. Wow! If you fall into certain categories (age, gender, prior health conditions) the “probability” and the “likelihood” of getting sick change. NOT the certainty that you’ll get sick… that’s what we have been trying to communicate for a long time in sociology.

Furthermore, labeling and symbolic interaction is powerful. And as we’ve (sociologists) always said, it’s good news and bad news. Emerging out of the data come labels like “High risk- lower risk.” As these labels take on a mind of their own we implore old folks to hunker down “more.” To the point that local, state and national leaders remind us that (through networking) if you’re a low-risker you still need to isolate (and we group people know a fair amount about isolates) yourself. This is because your thoughtless interactions could ultimately – through a chain of interactions – lead to “high-risk” grandpa. So in your daily interactions, “the life you save, maybe your Grandma Sadie.”

The bad news can also come from the strange, frightened look when you announce, “I’m from Seattle.” The Emerald City was initially labeled the “the epicenter” with all the implications that has. All this sows the seeds of a collective behavior chapter in a soc book. Did you stand in line at your local Costco or Walmart doing hand-to-hand combat over hand sanitizer? Were you the one who just bought a 56 pack of toilet paper but you don’t know why (At least somebody else didn’t get it!)? IF, “Yes” you can forge a path out of the crowd contagion swamp for your countrymen through both knowledge and experience.

And, then, those theories, methods and statistics. If you’ve had a solid lectures-worth of functionalism “Our health care system neither is structured nor has the capacity to handle an exponential outbreak” takes on new meaning. Maybe exponential and system take on any meaning at all for the first time for people watching the news! Perhaps the COVID19 fight sends a message that systems (those interacting, interdependent parts like institutions: government, economics, family, religion and education) are human constructions. They’re “built” and they can only handle so much. Sure people are part of them and in the end people make systems happen. But systems can change, adapt or fail and in the wake people may become well, sick or die.

Perhaps the methods for measuring social things has never been so clearly a problem in the public’s mind. Such is the case of the “mysterious denominator.” When we’re all struggling with a “how bad it is” fraction, be it new cases or deaths divided by “we-don’t have-enough-test-kits-to-measure-how-many-this-is” number. In addition, an epidemic’s spread has a graphic shape and human intervention can have something to do with reshaping it with a net impact of saving lives. The Centers for Disease Control helped us all understand through a fairly simple but powerful graph.

Much more can be said but perhaps we can take a moment to recognize the practical problem-solving value in so many of these concepts and tools. In closing, we must fully admit that many of these ideas and tools are not exclusively ours. But we’ve seen the value in using them as noteworthy team of professionals – some scientists, some not – nobly take on COVID19.

Stephen F. Steele is Professor Emeritus of Sociology and Futures Studies at Anne Arundel Community College.

A Slow Start on an Urgent Crisis: How Lack of Health Insurance Helps Explain Deficiencies in Coronavirus Testing in U.S. States by Angran Li and Allen Hyde

The coronavirus pandemic has brought to the forefront many pre-existing inequalities in society that often go unnoticed by some and taken granted by others. In the U.S., there have been several public debates about how the lack of health insurance relates to coronavirus testing and treatment. However, empirical evidence on this topic remains scarce, and we explore this topic in the current study, as well as the implications for exacerbating racial and class inequality.

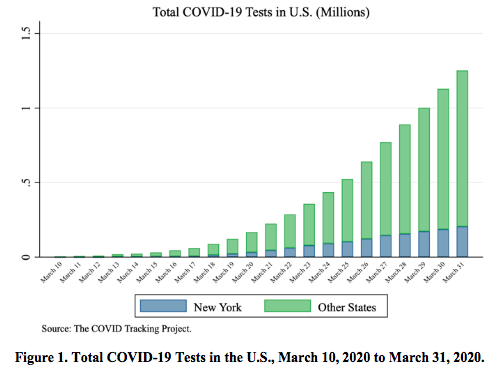

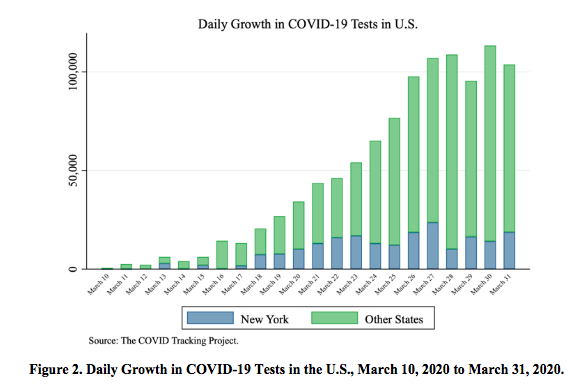

Despite significant increases recently, COVID-19 testing capacity in the U.S., has been slow compared to other affluent countries. As shown in Figure 1, the total number of tests increased from 4,858 to 1,048,884 between March 10 and 31, 2020. However, the testing capacity appeared to reach its limit due to the unprecedented demands in the last week of March. Figure 2 shows that since March 13, it took two weeks for the daily growth in testing to exceed 100,000. From March 27 to 31, testing growth stalled on average with 105,684 tests per day. In the epicenter New York, the testing capacity faced a greater challenge, as the daily increased number of tests stagnated on average with 15,976 tests per day between March 23 and 31. Local hospitals still faced enormous challenges in lifting their testing capacity. As we will discuss, the lack of testing and its relationship to lack of health insurance has important implications for exacerbating pre-existing inequalities.

Who is more likely to be uninsured in the U.S? Previous research suggests that adults over 18 and under 65 tend to be more likely to be uninsured because those under 18 are more likely to be covered by Medicaid or CHIP while those over 65 are often eligible for Medicare (Tolbert et al. 2019). Black and Hispanic or Latino adults are more likely to be uninsured than white, non-Hispanic adults (Tolbert et al. 2019). Adults who live in poverty or have part-time, part-year, or temporary jobs are also more likely to be uninsured because of our reliance on employer-based private insurance coverage. In 2018, 8.10 percent of the civilian noninstitutional population had no health insurance for all states. Lack of health insurance coverage varied substantially across states, ranging from 17.7 percent of the population lacking health insurance in Texas to only 2.8 percent in Massachusetts.

Health insurance is important for access to healthcare, thus it has important implications for coronavirus testing and treatment. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, one in five uninsured adults in 2018 went without needed medical care due to costs (Tolbert et al. 2019); and when they do seek care, they were over twice as likely as their insured counterparts to have had problems paying medical bills in the past 12 months. These bills can quickly turn into debt, which may not easily be paid off, particularly as the uninsured are more likely have lower incomes and savings. Thus, the uninsured may be more likely to avoid getting tested even if they show coronavirus symptoms early on, which may exacerbate health and socioeconomic disparities related to race, ethnicity, and class. This may increase community spread of the virus in their communities and workplaces, as well.

The reduced likelihood of uninsured adults not getting tested may still be the case even though President Trump has said that the $100 billion in aid given to hospitals through the CARES Act can cover the costs of the uninsured (Abelson and Sanger-Katz 2020); however, critics are concerned that these funds may be needed for overall hospital maintenance due to increased costs associated with the pandemic. Further, it is unclear that the public is aware that the federal government has claimed that they will aid in the costs of coronavirus testing and treatment. Even still, given that levels of social capital and social trust also affect coronavirus testing (Wu et al. 2020), there may be a lack of trust among the public that the government will actually cover those costs due to concerns that they are empty promises.

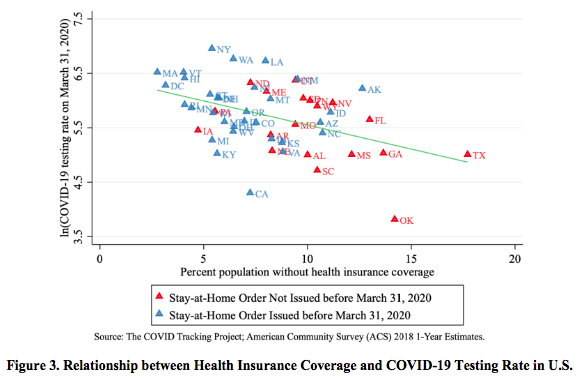

Using data from the COVID Tracking Project and 2018 American Community Survey 1-year estimates for U.S. states, we find that the percent population without health insurance coverage is negatively related to the state-level COVID-19 testing rate (R = -.44, p < .01), which is shown in Figure 3. Bivariate regression analysis demonstrates that for one standard deviation increase in percent without health insurance coverage (i.e., 3.1 percent), the COVID-19 testing rate is expected to decline by 27.4 percent. In additional analyses, these associations remain statistically significant, even after controlling for the confirmed COVID-19 case rate and whether the state issued a stay-at-home order, as well as state-level sociodemographic factors like percent Black, percent Hispanic/Latino, and poverty rates.

Overall, our findings reveal that state-level uninsured rates are an important factor predicting testing rates of COVID-19 during March 2020 when the virus rapidly spread across the U.S. Further, lack of health insurance coverage may exacerbate racial and class inequality in COVID-19 testing and subsequent hospitalizations and death. For example, a majority of COVID-19 related deaths reported in Louisiana are African Americans, accounting for 70 percent of the deaths, while African Americans only make up 30 percent of the state’s population (Doubek 2020). Similar patterns have occurred in other cities.

Our research also speaks to the policy efforts in the U.S. to promote universal public health insurance. The COVID-19 crisis has made this call more urgent. Our research suggests that the U.S. system relying on private health insurance, which leaves millions of Americans uninsured, is likely a hindrance to coronavirus testing, thus exacerbating the transmission of the virus and casualties associated with the pandemic. Additionally, our reliance on employer-based health insurance has another weakness to the COVID-19 pandemic: millions of Americans have either lost or are at risk of losing their jobs due to business closures or reductions of business activity (Simmon-Duffin 2020). Overall, the pandemic brings to light the importance of universal access to healthcare in the face of major public health crises.

References

Abelsen, Reed, and Margot Sanger-Katz. 2020. “Trump Says Hospitals Will Be Paid for Treating Uninsured Coronavirus Patients.” New York Times. April 3, 2020.

Doubek, James. 2020. “Louisiana Sen. Cassidy Addresses Racial Disparities in Coronavirus Deaths.” NPR. April 7, 2020.

Simons-Duffin, Selena. “Coronavirus Reset: How to Get Health Insurance Now.” NPR. April 3, 2020.

Tolbert, Jennifer, Kendal Orgera, Natalie Singer, and Anthony Damico. 2019. “Key Facts about the Uninsured Population.” Kaiser Family Foundation.

Wu, Cary, Rima Wilkes, Malcolm Fairbrother, and Giuseppe Giordano. 2020. “Social Capital, Trust, and State Coronavirus Testing.” Contexts Magazine. March 30, 2020.

Angran Li is an Assistant Professor of Sociology at Zhejiang University, China. His research interests include social stratification and inequality, education, family, urban studies, and quantitative research methods.

Allen Hyde is an Assistant Professor in the School of History and Sociology at the Georgia Institute of Technology. His main research areas are inequality and stratification, urban sociology, immigration, labor studies, and social policy.

Global Racial Capitalism as a Fundamental Cause of COVID-19 Disease Disparities in the World by Whitney Pirtle

In all parts of the world, COVID-19 is the culprit of premature death. Globally, as of late April, there are nearly two million confirmed cases of COVID-19, and over 200,000 deaths, reported to WHO. As more demographic data is shared within and across nations, we find that the most vulnerable populations are at greatest risk. Specifically, racially minoritized and economically disadvantaged populations are dying at disproportionate rates from COVID-19. I argue that what we are really seeing is how global racial capitalism works to have a fundamental impact on COVID-19 disparities across the world (see Pirtle 2020).

Racial capitalism, which comes from Black radical thought traditions, is the idea that racialized exploitation and capital accumulation are mutually constitutive. Most strongly articulated by Cedric Robinson, under this theorizing, racial capitalism created the modern world system because social ideologies and “the development, organization, and expansion of capitalist society pursued essentially racial directions” (Robinson 1983:2). Even in today’s neoliberal world, racially minoritized and economically deprived groups face mutually constituted capitalist and racist systems that continue to devalue and harm their lives (Clarno 2017); so much so that it is shaping who may live and who might die (Mmebe 2019).

Research in the sociology of health doesn’t often engage racial capitalism, but it has found that both racism and socioeconomic status are social conditions argued to be fundamental causes of disease disparities (i.e., Gee and Ford 2011; Lutfey and Freese 2005; Phelan and Link 2015; Phelan et al. 2004; Phelan, Link, Tehranifar 2010; Sewell 2016; Williams and Collins 2001; Williams and Mohammed 2009). Bruce Link and Jo Phelan (1995) argued that a social condition is a basic, fundamental cause of disease disparities if it influences multiple disease outcomes, affects disease outcomes through multiple risk factors, involves access to flexible resources that can be used to minimize both risks and the consequences of disease, and reproduced overtime through the continual replacement of intervening mechanisms.

Many have recently detailed how systemic racism and capitalism fundamentally shape COVID-19 and other health disparities in the U.S. (see also, Pirtle 2020), I extend these conversations to argue that global racial capitalism is a fundamental cause of COVID-19 disparities in the world. First, racial capitalism influences multiple disease outcomes, COVID-19 as well as diseases comorbid with COVID related deaths. For instance, global hypertension disparities are increasing in countries with constrained economic conditions (Mills et al. 2016), and place matters within countries for cultivating poor health, such as increased diabetes, in disinvested communities, (Gaskin et al. 2014). COVID-19 will impact these populations already impacted by poor health profiles at a disproportionate rate.

As a fundamental cause, global racial capitalism means the poor and racially minoritized are more vulnerable to negative health outcomes through heightened exposure to multiple risk factors. Homelessness, as one example, puts the poor, older, and families of color in California at increased risk for consequences of COVID-19. Yet, nearly two percent of the world is homeless, up to 20 percent lacks adequate housing, and rates of homelessness are also high in the global south; Manila, Philippines has the highest rate in the world. How can governments encourage sheltering in place when they don’t provide shelter and access to other basic needs such as water and food?

Indeed, COVID-19 is already impacting low and mid-income level countries at a distressing rate, and could devastate poor countries that colonialism and other racial capitalist enterprises have already harmed. A recent article in Foreign Affairs described the potential implications in African countries that, for instance, rely on planting or harvesting could have destructive consequences on food supply if forced to stop: “countries least able to impose physical distancing and perform contact tracing also tend to have the most overstretched health-care systems and the most precarious economies” (Malley and Malley 2020).

Capitalist gain has impeded adequate health care responses, amplifying additional health risks. Countries with more resources, like the U.S., have allegedly stolen ventilators slated for lower-income countries. Volunteer innovators printing important medical technologies report being threatened with litigation from larger corporations. COVID-19 is also exacerbating social class differences within countries like U.S. and Ghana, that can be linked to future health disparities.

Racism, supported by old notions of biological race differences, has seeped into conversations about COVID-19 immunizations around the world. French doctors have advocated for immunization trails to occur on African populations, and U.S. governments have authorized trials in Detroit, where large numbers of Black Americans are dying from Covid-19. Medical apartheid (Washington 2006) is sustained through racism and capitalism, and is raging its head again through the coronavirus pandemic and will contribute to increased inequities.

Flexible resources include knowledge, power, money, power, prestige, and beneficial network connections, all of which can alleviate the consequences of the disease, but all of which are constrained by racial capitalism. Freedom is specialized resource that has historically been restricted from people of color (Phelan and Link 2015). Border policies, detainment, and incarceration, all tied to racism and capitalism (Alexander 2007), further put vulnerable populations at increased risk for COVID-19, and limit access to resources used to buffer those risks.

Finally, intervening mechanisms proposed to ameliorate the relationship between racism, capitalism and health, such as public sanitation, immunizations, or even health care access, cannot fully eradicate the relationships because they are replaced by other mechanisms over time. For instance, the Ebola pandemic highlighted the human devaluation of people of color central to racial capitalism. Adia Benton (2014) wrote of Ebola how “the techniques of public health—investigation, surveillance, isolation and containment—collide with the medical ethics of care and compassion, … and viewed their [West African] bodies first and foremost as vessels for disease.” Similar devaluing and blame on Black bodies occurred in Chicago during the 1918 Spanish Flu. Undeniably, racism and socioeconomic disadvantage have persistent, significant, multifaceted associations with poor health in the modern world.

In sum, global racial capitalism sustains the modern world and is a fundamental cause of COVID-19 disparities in the world. To address the disparities Link and Phelan argue that “intervention must address inequality in the resources that fundamental causes entail” (1995: 89). In an open letter to us all, Chandra Ford and colleagues outline eight specific, health equity policy interventions to consider during COVID-19 that address fundamental causes. Though, true equity then, as demanded by Black international radicals may only be reached in liberation from racial capitalism through radical collective action.

References

Alexander, Michelle. 2007. The New Jim Crow: Mass incarceration in the age of Colorblindness. NY: The New Press.

Benton, Adia. 2014. “The Epidemic Will be Militarized: Watching Outbreak as the West African Ebola Epidemic Unfolds” Field Sights: Hot Spots, Cultural Anthropology Online, October 7, 2014. https://culanth.org/fieldsights/the-epidemic-will-be-militarized-watching-outbreak-as-the-west-african-ebola-epidemic-unfolds

Gaskin, Darrell J., Roland J. Thorpe Jr, Emma E. McGinty, Kelly Bower, Charles Rohde, J. Hunter Young, Thomas A. LaVeist, and Lisa Dubay. 2014. “Disparities in diabetes: the nexus of race, poverty, and place.” American journal of public health 104(11): 2147-2155.

Gee, Gilbert C., and Chandra L. Ford. 2011. “Structural Racism and Health Inequities: Old Issues, New Directions.” Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race 8(1):115–32.

Malley, Robert and Richard Malley. 2020 “When the Pandemic Hits the Most Vulnerable” ForeignAffairs.com March 31, 2020. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/africa/2020-03-31/when-pandemic-hits-most-vulnerabl

Mbembe, Achille. 2019 Necropolitics. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Mills, Katherine T., Joshua D. Bundy, Tanika N. Kelly, Jennifer E. Reed, Patricia M. Kearney, Kristi Reynolds, Jing Chen, and Jiang He. 2016. “Global disparities of hypertension prevalence and control: a systematic analysis of population-based studies from 90 countries.” Circulation 134(6): 441-450.

Link, Bruce G. and Jo Phelan. 1995. “Social Conditions as Fundamental Causes of Disease.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior. (Extra Issue):80-94.

Lutfey, Karen, & Freese, Jeremy. 2005. “Toward some fundamentals of fundamental causality: Socioeconomic status and health in the routine clinic visit for diabetes.” American Journal of Sociology, 110(5): 1326-1372.

Pirtle, Whitney. 2020. Racial Capitalism: A Fundamental Cause of Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic Inequities. Health Education and Behavior. Online First.

Phelan, Jo C., and Bruce G. Link. 2015. “Is racism a fundamental cause of inequalities in health?.” Annual Review of Sociology 41: 311-330.

Phelan, Jo C., Bruce G. Link, and Parisa Tehranifar. 2010. “Social Conditions as Fundamental Causes of Health Inequalities: Theory, Evidence, and Policy Implications.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 51(1_suppl):S28–40.

Phelan, Jo C., Bruce G. Link, Ana Diez-Roux, Ichiro Kawachi, and Bruce Levin. 2004 “Fundamental Causes of Social Inequalities in Mortality: A Test of the Theory.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 45:265–85.

Pulido, Laura. 2016. Flint, Environmental Racism, and Racial Capitalism, Capitalism Nature Socialism, 27:3, 1-16.

Robinson, Cedric. 1983. Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Sewell, Alyasah A. (2016). The racism-race reification process: A mesolevel political economic framework for understanding racial health disparities. Sociology of Race and Ethnicity 2(4): 402-432.

Washington, Harriet A. 2006. Medical apartheid: The dark history of medical experimentation on Black Americans from colonial times to the present. NY: Doubleday Books.

Williams, David R. & Collins, Chiquita. 2001. Racial residential segregation: a fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Reports 116(5): 404–416.

Williams, David R., and Selina A. Mohammed. 2009. “Discrimination and Racial Disparities in Health: Evidence and Needed Research.” Journal of Behavioral Medicine 32(1):20–47.

Whitney Pirtle is an Assistant Professor of Sociology at University of California, Merced.

“A Crowdsourced Sociology of COVID-19” by Jenny L. Davis, Erika Altmann, Naomi Barnes, James Chouinard, D’Lane R. Compton, Amber R. Crowell, Peta S. Cook, Simon Copland, Laura Dunstan, Katharine Gary, Anna Jobin, Christopher Julien, Helen Keane, Gemma Killen, Hùòng Lê, Jennifer Lê, Stewart David Lockie, Ben Lyall, Maitahitui, Alexia Maddox, Annetta Mallon, Bianca Manago, Lizzie Maughan, Daniel Morrison, Chantrey J. Murphy, Mikayla Novak, Rebecca Olson, Elaine Pratley, Hedda Ransan-Cooper, Timothy Recuber, Deana Rohlinger, Judy Rose, Suzanne Schrijnder, Naomi Smith, Holly Thorpe, Francesca Tripodi, Samantha Vilkins, Matthew Wade, Apryl Williams, Nathan Wiltshire, and Mark Wong

These are radically disruptive times, ripe for sociological analysis. Yet most sociologists, like most humans on the planet, are distracted, distraught, uncertain, and overwhelmed. Our thoughts are reeling, but not fully formed. This piece captures and catalogues the ‘brain sparks’ from a diverse array of thinkers in the academic community. These are one -or- two-line insights (sometimes in the form of aspirational paper titles) that shine light on the complex social dynamics emerging in real time. The idea is to hang onto these insights, to give them a home, and, perhaps, a place from which to grow.

Data for this paper come from a call that the first author sent out on Twitter, asking sociologists for their best hot takes. The call migrated and snowballed to other social media platforms and continued through email exchanges. Everyone who contributed, in any form, is included as an author. Some contributors shared a few words, others a few sentences, a small number wrote more extensively. Each contribution contains a nugget of sociology, valuable in its own right, and also worth investigating further.

The body of the paper documents themes that developed from the initial call. Each theme is exemplified by a selection of especially illustrative Tweets or messages. The data collection and analyses are driven more by enthusiasm than rigor. The sample is far from random and the topics hastily organized. In its open imperfection, this paper’s methodology is on-brand with the present moment: we are all just doing our best.

The collection of ideas presented herein are touched by the traces of classic and contemporary theorists—Merton, Mead, Simmel, Marx, Butler, Jasper, Ahmed, Goffman, Bourdieu, Crenshaw and others—recast through the prism of COVID-19, dashed out sans reference in the virus’ wake.

Social Connection Across Physical Distance

Sociologists of digital technologies have long battled the misnomer that mediated interactions are intrinsically less real and less valuable than face-to-face encounters. Stemming the spread of COVID-19 has entailed a sudden and widespread shift online as communities struggle with containment. With shared physical space becoming a public health hazard (and in some instances an illegal act), contributors highlight the ways people find intimacy and connection through screens. Mark Wong points to the baked-in assumptions of the phrase “social distancing” and Alexia Maddox channels a larger collaborative research program that addresses modes of intimacy and pleasure via digital media.

Definitely the choice of the word ‘social distancing’ and not ‘physical distancing’ highlighting how many (especially authorities) still mainly think of social as being physical and neglecting the digital (@UoG_MarkWong).

How can the virtual support us to touch each other in lieu of other forms of tactility? It strikes us that the responses to the virus have been about reconfiguring pleasures (@alexiamadd).

Moral Claims-Making

In moments of uncertainty, normative and moral claims can rise to the fore. Contributors point to two types of moral claims-making that feature in COVID-19 discourse. One is about who is to blame for the virus and the other about how one “ought” to conduct the self under conditions of a new normative order. These moral claims fall along lines of race and gender in ways that reflect and reinforce white and masculine privilege. Apryl Williams points to anti-Asian sentiment and moral panic, while Hùòng Lê addresses normative demands of motherhood.

I’ve also been thinking about how this virus has given us a moral holiday. People think in this instance, it’s ok to be racist. They are wrong. It’s not! But it is clear that when we are taking about a war on COVID, it becomes easier for that war to extend to ‘Yellow Peril’ (@AprylW).

This [school closings and physical isolation] disproportionately affects women and women with children. Work from home and homeschool and be judged if your kid gets ‘too much screen time’ and French fries (@huong_t_le).

Social (Dis)location

Contributors point to the implicit and explicit ways race and class figure into physical bodies in physical space, particularly with regard to housing for the sick and the well. For example, Jennifer Lê, a sociologist in Washington state, describes the disjuncture between the demographics of those who disproportionately require quarantine (white, affluent) and the location of make-shift quarantine facilities in Seattle (low income neighborhoods with racially diverse residents). Amber Crowell, in turn, discusses the problem of “business as usual” as people lose their homes to eviction.

We are seeing the wealthy and white being more protected here and their lives valued higher (Jennifer Lê).

My mind is always on housing…evictions being treated as business as usual in the middle of a global pandemic is some next level privileging of owners over non-owners (@acrowellsoci).

Contested Rationality

There is no playbook for appropriate behavior in a pandemic. This leaves various responses open to interpretation and the subjects who enact those responses open to evaluation and judgement. Contributors point out that behavioral evaluations are often fitted to existing patterns of power and inequality. Judy Rose, for example, highlights emergent standards of rationality tied to an ‘us’ versus ‘them’ mentality, and Simon Copland asks whose behavior does (and does not) get construed as ‘panic.’

[T]he ‘us’ and ‘them’ or ‘othering’ is really playing out in conversations that are starting to label – the crazy irrational panic-ers (young, poor, hoarders) vs the sane rational (mature, sensible, white, middle class) (@DrJudyRose).

Coronavirus has shown the power dynamics behind ‘panic.’ The panic of the political class is considered needed and essential, while the panic of everyday people is chastised as completely irrational (@SimonCopland).

Mental Health

With a strong global focus on physical health, it would be easy for mental well-being to take a backseat. However, the times are uncertain, routines are disrupted, and people are stuck in their homes. Katharine Gary wonders if social isolation measures may evoke of a pandemic of depression, and D’Lane R. Compton points to the closure of exercise facilities and the related mental health effects for gender non-conforming people.

I just want the idea that mental illness/substance use can cause deaths like a virus to be part of the conversation. We know there is research supporting the idea of emotion contagions, physical distress contagions, stress contagions, and (obviously) physical illness contagions, so why aren’t mental illness contagions being considered in all this talk about contagions? (@KatieGarySoc).

What if I die without my gym? Of what if I die without my routine? Like in my extremely trans dominated gym—not working out, and with intensity, can lead to really dark places mentally. Space is an issue, and how to do the body/mental work (@drcompton).

Online Education

Several contributors address the implications of education moving online, often drawing on firsthand experiences of a harried transition over the past two weeks. Daniel Morrison talks about the architecture of learning management systems (LMSs) and Maitahitui focuses on digital access and inequality,

The Swiss Army knife LMSs are a major part of the problem. They’re designed for everyone, so they give too many options. One thought I keep having is: LMS companies are all about scale. They want everything in one system so it can be tracked, measured, assessed…a neoliberal technology, sold to faculty as a way to keep (and reuse!) class materials (@danielrmorrison).

Working with sociology students and checking out their ability to engage if we have to suddenly teach online (likely) I discover rich data about all the carparks where you can get good wireless. Burger King, McDonalds, KFC. Poverty is alive and well in Aotearoa NZ (@Maitahitui).

Role-Taking and The Public Good

Role-taking is a classic concept in sociology that refers to putting the self in the shoes of another. Although the plight of the global community has never been more common, the capacity to account for others’ needs appears lacking. Elaine Pratley points to age-based conflict and Nathan Wiltshire poses several explanations for failures to act outside of self-interest. In turn, Timothy Recuber calls on systemic enforcement of communal responsibility rather than models based on individual choices.

The times are indicative of generational conflict—old people don’t care about climate change because they’re going to die anyway. Young people aren’t vigilant about COVID because they think their youth grants them immunity. How to develop care for your generational neighbour? (@elainepratley)

I’m interested in compliance/failure of people to quarantine (personal-directed) or lockdown (city-wide). Is it a failure of empathic concern? Self vs. Other trade-ff (anti-social intention)? Lack of information/education? Broken trust with authoritative sources? (@nathwiltshire).

Been thinking about how individual empathy is a poor substitute for clear gov’t guidelines, i.e. (lack of) social distancing or panic hoarding (@timr100).

Social movements and Collective Action

The sociological literature on social media and social movements have traced both the opportunities and perils of mobilization as movements and activism incorporate digital social technologies. In this vein, contributors both worry about the effects of physical separation on social movements and at the same time, imagine new possibilities for collective action and solidarity.

[I wonder about] Pandemics and the demise of social movements. Well, the energy surrounding them and just about everything else (@DeanaRohlinger1).

I’m also wondering how collective expressions of solidarity for e.g. casual [“Casual” refers to freelance hourly workers. In academia, these are the adjunct instructors.], renters, how will these be framed and materially articulated and what role will digital infrastructure play? Will people crowdfund their casual mate? (@hedda_r).

Changing Nature of Institutions

Social institutions—educational, religious, economic, familial—are rooted in entrenched logics that, in the face of a global pandemic, no longer apply. Contributors address these institutional logics and speculate about new institutional formations in a post-COVID-19 world. Anna Jobin, for example, presents research questions about the redefinition and remuneration of frontline occupations and Laura Dunstan speculates about the makeup (and shakeup) of family structure.

How lockdown reveals what is considered to be a ‘systems relevant’ occupation that can still be carried out, how this is defined differently between different nations/regions? How will this categorization play out once this is over? How will the shifted formal valuation of occupations be negotiated socially and politically post emergency?(@annajobin).

What will this do to the shape of families? Will expanded connections be strengthened or will they shrink? How will our practices of care be altered and in turn alter the fabric of our families? (@laura_dunstan_).

Rituals of the Everyday

COVID-19 has wrought seismic upheaval and yet, the mundanities of daily life persist. Harking back to the foundations of symbolic interaction, several contributors spotlight the rituals of everyday life, as individuals and families search for normalcy in an extraordinary moment. Helen Keane, for example, frets over appropriate attire for Zoom work meetings, and Chris Julien offers a provocative (and pun-filled) paper title about newly emergent norms.

Presentation of work self becomes complicated. I see folks complaining about expectation to dress ‘professional’ for Zoom meeting. OTOH as someone who has work clothes vs non-work clothes, it feels wrong to put on work outfit & wrong not to (@HelenKea).

“Til Disease Do Us Part: Novel Norms Amidst a Novel Virus” (@ChrisJulien22).

Local Meets Global

Several contributors describe the simultaneous tension between hyper-locality and hyper-globalization, made clear through the response to, and material conditions of, COVID-19. Naomi Smith highlights local-global supply chains and Holly Thorpe discusses embodiment and transborder mobilities

It’s become clear that we have lost a level of distinction between the local and the global. Most of our food is manufactured locally but people are panicking because we know that we are also deeply entangled in global supply chains without quite knowing where +how…I have thought about this a lot re: Brexit [and] the materiality of their borders and how they vanish and reappear in a number of ways, how countries pull away from each other in an attempt to overcome the tangibility of geography (@deadtheorist).

I’m thinking about the many (im)mobilities involved in the COVID-19 pandemic. How the virus travelled with/on bodies on planes and boats (@hollythorpe_nz).

Horror and Hope

A sense of ambivalence emerged among contributors as they pointed to the hardships now and in the future, but also the latent effects that would be implausible without the transformative fallout of something like a global pandemic. The phrasing ‘horror and hope’ comes from Matt Wade, one of the authors, who articulates the tension especially well. Others follow suit by finding the silver linings in COVID-19 and offering optimism amidst catastrophe. Social connection, environmental reprieve, economic justice, and a clear-eyed look at structures of inequality all rise from the dust of disaster. These messages of ambivalent hope close out the piece, because such glimmers serve us now, more than ever.

I’m caught between horror and hope. Horror from the cretins who say ‘well, from a purely economic perspective …’. But hope from those building mutual aid, and where we might better grasp our collective vulnerability and interdependence, finding new ways to care for one another (@MattPWade).

[COVID-19 has] Latent effects with ostensibly progressive outcomes–e.g., progressive economics, lower pollution rates, reimagined possibilities of all sorts (@jamesbc81).

[H]ow are these sticky emotions (a la Ahmed) affecting our emotions about climate change? The only good news stories are about how lockdowns in Italy and China are having an ameliorative impact on the environment (e.g. clean canals, less pollution) (@RebeccaEOlson).

For decades sociologists have been drawing attention to labor inequalities and access to the internet. Only now, in the middle of a global pandemic are the everyday inequalities becoming more visible. From lack of internet access to unpaid sick leave to universal basic income – we are finally coming to terms with these grave divisions in our society (@ftripodi).

Jenny L. Davis (@Jenny_L_Davis), Erika Altmann (@propertypolicy), Naomi Barnes (@DrNomyn), James Chouinard (@jamesbc81), D’Lane R. Compton (@drcompton), Amber R. Crowell (@acrowellsoci), Peta S. Cook(@PetaCook), Simon Copland (@SimonCopland), Laura Dunstan (@laura_dunstan_), Katharine Gary (@KatieGarySoc), Anna Jobin (@annajobin), Christopher Julien (@ChrisJulien22), Helen Keane (@HelenKea),Gemma Killen (@gemkillen), Hùòng Lê (@huong_t_le), Jennifer Lê, Stewart David Lockie (@StewartDLockie), Ben Lyall (@benlyal), Maitahitui (@Maitahitui), Alexia Maddox (@alexiamadd), Annetta Mallon (@AnnettaMallon),Bianca Manago (@BiancaManago1), Lizzie Maughan (@lizziemaughan), Daniel Morrison (@danielrmorrison),Chantrey J. Murphy, Mikayla Novak (@NovakMikayla), Rebecca Olson (@RebeccaEOlson), Elaine Pratley(@elainepratley), Hedda Ransan-Cooper (@hedda_r), Timothy Recuber (@timr100), Deana Rohlinger(@DeanaRohlinger1), Judy Rose (@DrJudyRose), Suzanne Schrijnder (@SuusSchrijnder), Naomi Smith(@deadtheorist), Holly Thorpe (@hollythorpe_nz), Francesca Tripodi (@ftripodi), Samantha Vilkins (@samvilkins),Matthew Wade (@MattPWade), Apryl Williams (@AprylW), Nathan Wiltshire (@nathwiltshire), and Mark Wong(@UoG_MarkWong)

How COVID-19 Can Inspire Us To Change Society for the Better in the Long Run (If We Take It Seriously) by Jacob Thomas

Social critics typically have the role of highlighting negative or problematic aspects of society, particularly in periods during which everything appears to be going well; however, during difficult, uncertain and chaotic periods of history, they can perform a potentially equally important role of pointing out positive changes that can emerge out of what is a profoundly terrible catastrophe for humanity. This paper highlights ways COVID-19 simultaneously exposes fundamental problems in societies and necessitates that we address them if we are all not to collectively suffer more now and later when another pandemic arrives. I recognize that some of these examples may seem to be mentioned too-soon while we have other more critical needs to cope with the present disaster, the changes that have happened possibly temporary, and this is by no means an exhaustible list—though I do hope they will stimulate others to offer their own examples. I propose for a moment we view the “exogenous shock” of a virus as violently dislodging us from harmful patterns and structures in society and set us on a new path of progress toward a more humane society. But such changes will require enormous effort by all members of society to enable us to both cope with the crisis and (more importantly in the long run) better prepare us for another such shock in the future. Therefore, I use the word “could” rather than “may” because I believe that all I mention is hypothetically contingent upon us whether we choose to make changes to our society that will make us more robust to a pandemic. Fortunately, I will mention several ways in which we have already immediately seen governments try resolving problems that they have ignored for years, which suggests that it is not so difficult to make progressive change but only requires the collective will to do so.

- COVID-19 could further expand non-geographically bounded online communities and provide more opportunities to reduce loneliness.

Although physical distance is important to reduce the spread of a disease, loneliness is also emotionally and mentally harmful and can compromise the immune system, especially for stigmatized, disabled and elderly individuals that to be more isolated even in non-pandemic times. A growing individuals now need to learn how to live online by using technologies like zoom to create co-working spaces, parties, church services, alcoholics anonymous meetings and even academic seminars. They will thereby meet people they likely would not otherwise, which will aid them during future disasters. Due to their physical constraints and isolation, people may become less exclusionary and more open to new members that share common interests. This may also bridge gaps between social cliques and more effectively facilitate the exchange of information and ideas otherwise confined to local areas.

- COVID-19 could foster intergenerational solidarity:

Solidarity is a concept that some trace back to the Catholic social philosophy and that relates to a commitment to the common good and altruism. Some argue that since elders are ceteris paribus more vulnerable to dying from the virus than younger people. This may foster intergenerational solidarity that has been in decline recently with resentment about intergenerational injustices and idealism between relatively older and younger generations. As elder and on average wealthier individuals become more dependent on the younger to provide them with cleaning, transportation and food, relatively younger people in Western societies may not only benefit economically but also learn to appreciate and respect their elders and the fragility of life.

- COVID-19 could encourage society to recognize and remedy the digital divide:

The only limit to the above positive trends is that not everyone has access to such technologies. Yet this makes soon bridging the digital divide even more imperative, and may explain why universities and schools have begun pushing for long-term laptop loans and programs to provide internet access to the under-resourced.

- COVID-19 could largely and at least temporarily eliminate the problem of homelessness.

California recognized that homeless people, due to their exposure both to the outdoor urban environment and destitution, are extremely vulnerable to catching a disease. Previously, governments have done little to house them by taxpayers’ expense, in part because wealthy homeowners oppose the construction of affordable housing. But California has taken the lead in recognizing COVID-19 makes the lack of shelter and affordable housing a threat to public health. Governor Gavin Newsome therefore has begun purchasing hotels (which due to the severe drop in travel have not been profitable recently) to house its roughly 130,000 homeless people.

- COVID-19 could largely and temporarily abolish prisons and detention centers.

Relatedly, various officials in the criminal justice, immigration enforcement and refugee management systems have also realized that detaining massive amounts of people in prison, immigrant and refugee detention in such cramped and insanitary conditions is likely to exacerbate an outbreak, since many people that work in such institutions also go outside and will spread the disease they catch in such institutions. As the federal government scales back its Immigration and Customs Enforcement operations, some prison and detention abolitionists have intensified their demands to end such systems to protect public health.

- COVID-19 Could Encourage Governments To Provide Guarantees of Paid Sick Leave for All Workers:

As Fran Marion points out, for decades, over a million workers that prepare food for tens of millions of people daily have gone to work with contagious diseases like influenza—in large part because the industry only pays them around $12/hour.

As CDC elements point out, about 20% of food service workers living paycheck to paycheck cannot afford to stay home when sick. Companies like McDonalds say that have started offering sick leave to quarantined workers, but this only applies to workers in corporate-owned companies, not workers at 95% of McDonalds stores, which are franchises. Recently Congress moved to pass a bill that offers more sick leave, but only with respect to the COVID-19 virus (not the flu or future disease outbreaks) and only to companies that have less than 500 workers, which only covers 20% of workers. As the disease spreads through the population and kills more people, government officials may face greater pressure to follow the leads of companies like Darden Restaurants (the owner Olive Garden) in ensuring that all paid employees receive sick leave.

- COVID-19 could increase safety nets for aspiring homeowners, renters and workers:

In not only the US but also many European countries, governments have suspended mortgage payments, given people relief from evictions due to missing rent payments, subsidized company’s payrolls to discouraging dismissal of workers, and delayed taxes—relief that governments has not provided as much as in the past. Democrats within the US are also pressuring Republicans pass unemployment insurance (which many gig workers lack), forgiving student loan payments, assisting with rent payments, giving more food stamps, and stopping home foreclosures. Workers like those that work in increasingly important and risky occupations like retail, food preparation, healthcare and emergency services are especially. For this reason progressive companies like United Natural Food have begun to offer them both monthly and hourly bonuses to their wages to attract more future employees.

- COVID-19 could encourage a shift from in-kind to cash aid.

Historically, many legislators in government have preferred aid-in-kind (e.g. food stamps) over cash transfers, but many scholars and practitioners of economic development have found cash transfers to be more effective. Some have critiqued that greater cash transfers should primarily go to cash strapped businesses and those that lose their jobs rather than those minimally affected by the virus, cash transfers can beneficial than traditional forms of aid if we have more targeted and well-thought out programs (Pearlstein 2020).

- COVID-19 could demonstrate that border control and travel bans are ineffective for preventing the inevitable spread of disease and other problems.

Many have emphasized because China—once it recognized COVID-19 as a problem—did its best to control internal migration and the other governments like the US blocked most travel from China so they had a bit more time to prepare. But such travel bans have both been economically damaging and futile at completely stopping the eventual global spread of the virus because many people can easily travel to other countries indirectly and many are asymptomatic. Such bans prevent the international flow of equipment and materials (e.g. masks, ventilators) necessary to stop the spread of the disease within countries. As a result, migration control has devolved to the level of the household, with state orders for people to “shelter in place” or “lock down,” which effectively obviate border controls and travel bans. When facing a virus, the only border that protects the individual is that between their self and other individuals—and an imposition of this border can offer us a renewed appreciation of how harmful larger borders can be for those they exclude.

- COVID-19 could convince societies that health care for all is so critical for the survival of everyone in the long run:

Historically many have conceptualized healthcare as an exclusionary, private individual commodity. This is even the case in societies that lack universal healthcare, which they frequently portray as a policy of individual justice. Despite diseases like HIV-AIDS, SARS and measles that periodically eradicate portions of populations, neoliberal governments have defunded public health programs for years so that they are quite vulnerable to disease outbreak. COVID-19 makes universal healthcare a desirable, even irrespective of any racial animus or classist beliefs that has prevented its adoption.

Nothing I have written above, again, is to disavow the fact that COVID-19 has had a tremendous negative impact on society, particularly due to the way it has destabilized the “normal” functioning of society and the economy. But it does reveal to us that much of what most people found to be acceptable about society was extremely problematic. Thomas Piketty demonstrated that historically inequality—one of the most pressing problems today—has decreased after major depressions and wars, and therefore COVID-19 may have a similar potential in the coming decades. Yet history also has demonstrated that after societies have recovered from such catastrophic shocks by implementing such social safety nets like the New Deal in the US, they have over time gradually dismantled them with neo-liberal reforms to increase individual “efficiency” and “freedom,” suggesting that history is cyclical rather than progressive, or even a one-step-forward-two-steps-back progression. But if one prefers to be optimistic and struggle to build a society in which a pandemic will not have such a catastrophic impact, one can see COVID-19 as an important historical example of why members of societies should both build and maintain a new structure of our society, politics and economy that when the next pandemic arrives, we are better prepared to resist it.

References

Beyer, G. J. (2014). The meaning of solidarity in Catholic social teaching. Political Theology, 15(1), 7-25.

Wu, Z., & McGoogan, J. M. (2020). Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Jama.

Sacramento Bee, “California plans to use private hotels, motels to shelter homeless people as coronavirus spreads”, 3/15/2020 https://www.sacbee.com/news/local/article241216061.html

Fran Marion, ‘If I Caught the Coronavirus, Would You Want Me Making Your Next Meal?’ New York Times, 3/20/2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/19/opinion/mcdonalds-paid-leave-coronavirus.html

Waldman, .“Can we rescue the U.S. economy? Here’s where Democrats and Republicans disagree.” Washington Post, 3/20/2020 , https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2020/03/20/can-we-rescue-us-economy-heres-where-democrats-republicans-disagree/

Ferguson, J. (2015). Give a man a fish: Reflections on the new politics of distribution. Duke University Press. Fiszbein, A., & Schady, N. R. (2009). Conditional cash transfers: reducing present and future poverty. The World Bank.

Piketty, T. (2014), Capital in the 21st Century, Chicago.

Jacob Thomas is a Doctoral Candidate at University of California, Los Angeles.

Comments 29

jenny

May 2, 2020This is the best thing ever we had been looking for the robux generator online.

Dominick

May 3, 2020Nowadays, we can see that our world is facing a great crisis only because of this COVID-19 and if this time we faced any other problem or diseases for our body then it will be very hard for us to recover it. Also recently my father was troubling with hearing problem as his ear also give lots of pain but after visiting lij hearing and speech center from there we really got an amazing solution and now my father is using digital audiology but it seems you are not deaf actually.

vin lookup

May 12, 2020I have read through other blogs, but they are bloated and more confusing than your post. I hope you continue to have such quality posts to share with everyone! I believe a lot of people will be surprised to read this article!

mika

May 12, 2020There are many people looking for posts like this. I have received quite a lot of news from this article.

boxnovel

adnanameen9

May 18, 2020Well! This is very detailed and full of informative article. I agree your most of the points and you make take a look of this article where you able to write the effect of COVID 19 on product inspection types of services. May it will be very useful for the people who want to know more about it.

chrisgail

June 19, 2020Corona-Virus has covered the whole world and It is very difficult to control it that is why we can not give you the prediction about the future about our society.

cheap dissertation writing service

Mehrunissa

June 26, 2020"Thank you for sharing such great information.

It has help me in finding out more detail about future outbreakes of COVID-19"

Raymond

June 26, 2020I am getting afraid day by day.Corona virus has a mysterious power to ingest into human connective tissue which lies in the respiratory track of human. So first symptom could from common cold sore throat etc. You may Visit here to know more information that will let them know how to play adult online games.

vex 3

July 21, 2020Very helpful to share. You are a great author. I will definitely bookmark your blog and may come back someday Thanks for a great post. Please continue to uphold!

fnaf

Elisabeth

August 23, 2020Something terrible is happening in the world right now. Every day, a lot of problems pile up, along with writing an essay. But if they can help you with it https://getnursingessay.com/, then solve the rest - we are not able to. We just have to wait for things to get better

Laura

September 22, 2020I agree that a lot has changed during the coronavirus pandemic. I constantly felt that everyone around me was sick. I could not leave the house calmly. After the second week of sitting at home, I began to experience fits of fear. Unfortunately, I never managed to suppress them, and even during the pandemic I had to undergo therapy with a psychologist. On the advice of my family, I used the help of https://drmental.org/ Thanks to them, I realized that I could survive the pandemic healthy and without harming my psychological state.

Steve martin

September 30, 2020We have a responsibility to take care your self and others and create social distancing and stay secure.

Sport and Leisure Discount codes

Alia Parker

October 31, 2020A virus is so dangerous for our health we can very clearly assume that now. Thanks for giving such an effort for us. To protect such kind of viruses we need to select some essential things for us like choosing insect repellent. It protects our body from a variety of viruses and bacterias. We all need to look at our own health at this time. Walking frame

Lina Cartina

November 7, 2020Because covid19 I post two times more video on tiktok and buy tiktok likes from here https://soclikes.com/buy-tiktok-likes

Anna Coblin

December 21, 2020Thanks for informing us whit this great blog.

Mark

January 18, 2021Great post, thanks

Lincoln Bailey

February 8, 2021Great site!

Dave Seth

May 26, 2021Nice Blog.!

Poll

July 7, 2021Nice post!

Richard Madden

September 15, 2021A lot of cool information is on this blog. I am very happy I see this page.

aqua

October 26, 2021excellent

Farid Elsion

January 20, 2022Amazing!

nemroq

January 20, 2022I love this article, it is been me so much emotions!

Erek Delin

January 20, 2022Aamazing!

erek delin

January 30, 2022amazing!

erek delin

January 30, 2022Love it!

eCutPrice

February 10, 2022I began to experience fits of fear. Unfortunately, I never managed to suppress them, and even during the pandemic I had to undergo therapy with a psychologist. On the advice of my family. A lot of cool information is on this blog. I am very happy I see this page.

Nidhi

May 4, 2022Covid is the very dangerous for the future society.

tablets

July 25, 2022We are creative, compassionate, and brilliant. We can see this in our healthcare workers, frontline workers, first responders, teachers, medical researchers and all the people trying to make a living in this tough time. It’s an uphill road, but we can make it to the top.