Q&A with Dr. C.J. Pascoe

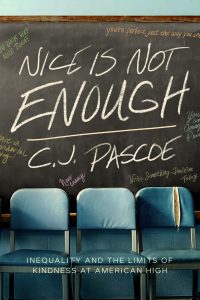

We are thrilled to welcome C.J. Pascoe to the Contexts Blog in celebration of C.J.’s new book, Nice Is Not Enough: Inequality and the Limits of Kindness at American High. In this post, blog editor Elena van Stee chats with C.J. about American High School’s culture of kindness—and why it’s insufficient to challenge systemic inequalities embedded in this school and broader society. You can watch the full interview above and find lightly edited excerpts from their conversation below.

Elena van Stee: C.J., you describe American High as a school characterized by kindness—a school that students described to you as “full of violently accepting people.” To begin, why don’t you introduce our audience to this very special high school and tell us a little bit about how you ended up there in the first place.

C.J. Pascoe: I ended up there by accident! I think the beauty of ethnography is that you can end up someplace and learn something no matter what. And that’s my general approach to research: once I get into a school, I’m like, “Well, what is it that I’m going to learn here? How is it different or similar to other places? What can it tell us about how the world works?” That’s always my mindset.

When I walked into American High, I knew it was going to be different from the school in my previous study because there were these signs everywhere. The signs said things like, “There’s no room for hate” and “You look beautiful today” and “Empowered women support women.” And it wasn’t just the signs—teachers talked like this, students talked like this, graduates talked like this, parents talked like this. It’s a really special, warm and welcoming place that I that I fell into.

EVS: What’s not enough about being nice?

CJP: I remember at one point, I called a friend and I said, “I think I’m gonna write a happy book. I’m gonna write a book about how people love each other.” And then I saw some things happen. Something really crystallized for me the day of the senior assembly. So, the assembly opened with the show choir singing the national anthem. And as the choir was singing, I watched out of the corner of my eye as a teacher dropped to one knee, engaging in the protest against racist police violence that had been started and popularized by Colin Kaepernick. Several other teachers drop to one knee, joining in the protest.

CJP: I remember at one point, I called a friend and I said, “I think I’m gonna write a happy book. I’m gonna write a book about how people love each other.” And then I saw some things happen. Something really crystallized for me the day of the senior assembly. So, the assembly opened with the show choir singing the national anthem. And as the choir was singing, I watched out of the corner of my eye as a teacher dropped to one knee, engaging in the protest against racist police violence that had been started and popularized by Colin Kaepernick. Several other teachers drop to one knee, joining in the protest.

Then I watched what happened in the weeks that followed, which seemed to contradict the messages of love and kindness that I had observed throughout the school. People were incredibly upset that the teachers had done this. People called it “political,” and the school district ended up writing letters to each of these teachers saying that kneeling to protest racist police violence was considered a political act and that if they continued to engage in political activities, they would lose their jobs.

That was the moment when I thought, “Well, I’m not sure that’s political. They’re not advocating for a political party!” In fact, these teachers’ actions seemed quite in line with the messages that the school had been giving. And so it got me thinking about what work the word political did. I started to pay attention to the other contexts in which the word political was used. For example, the principal used it when kids mounted an anti-gun violence protest. He said, “The schoolhouse is no place for politics.” And the football social media page said something like, “We don’t have any space for negativity here. Don’t bring up race, religion, or gender.” Because those things are all political. And what became increasingly clear is that by using the word political, the school and the staff were saying that anything that addresses inequality is off limits.

And that’s where the kindness discourse stops. You can’t solve inequality with kindness. The kind of racism they’re okay with talking about is the kind where people are individually mean to one another—because that can be solved by kindness. But when we’re talking about systemic racial inequalities—racial inequalities that are built into a social system—these inequalities can’t be solved by kindness. The school curtails individuals’ ability to address these issues by calling them political and saying “we can’t deal with that during the school day.” The word political signals the limits of what kindness can do.

EVS: I’m going to ask you a question that I think most academics fear, which is: what do we do? What’s the alternative? If kindness isn’t enough, being nice isn’t enough, what is a better response for schools? And for us in general?

CJP: I’m actually really happy you asked that. Because I thought a lot about what it meant to be a sociologist as I was writing this book. We’re really, really good at pointing out problems. And one thing I learned from the people at American High is that pointing out problems isn’t enough. I was embedded with all these people who really did want to make the world a better place. And I would be doing them a disservice if I just walked in pointed out problems and didn’t point out solutions.

I was writing this book in some of the hardest days of the pandemic, and I was thinking about what we as sociologists could offer to help make this world a less horrifying place. And so I began to read what people were writing about in the pandemic. And Gregg Gonsalves and Amy Kapczynski wrote a piece about the politics of care, which argues that we need to put human needs at the center of social policy. This inspired me to think about what a politics of care would look like. To me, a politics of care means systematizing care.

Here’s an example. I mentioned earlier that the principal told students they couldn’t have a school walkout because it would be considered political. Well, a bunch of students went on this walkout anyway. In doing so, they risked failing final exams and being marked with an unexcused absence (which could get them in a lot of trouble). I looked at what other schools did, and I discovered there was another school that changed the bell schedule so that students could walk out without a penalty. Other schools put gun violence at the center of assemblies and curricular concerns. Instead of saying, “we can’t talk about this, it’s political,” these other schools were saying, “this is a time to learn about gun violence.” And so one of the things I think about in terms of systematizing care is that we should be building ways to address these topics into the school structure, rather than leaving the responsibility to individual teachers.

EVS: I’ve got a question about the article that you published with Sarah Diefendorf in Social Problems. In this article, you draw parallels between the school you described in Nice is Not Enough and a conservative evangelical megachurch. To me at least, this seems like an unlikely pairing. What do these places have in common, and what lessons did you take away from the comparison?

CJP: Thank you so much for asking about that. So, my frequent coauthor Sarah Diefendorf and I were on the plane to ASA in New York in 2019. She was in the middle of writing her book The Holy Vote, which is about an evangelical megachurch. I had just finished fieldwork for Nice is Not Enough. We were chatting about what we had seen in our respective field sites, and I was talking about this moment when the young folks I was studying had put on a Black Lives Matter display. There were these huge trifold posters portraying images, names, and stories of Black Americans who had been victims of racist police violence. And in front of these memorials, there were tables covered in butcher paper where students could react. Many students reacted by demanding racial equity, changes, etcetera. But about half the comments said things like “Can’t we just all love one another?” and “We need to be kind.” As if love and kindness could solve systemic racist police violence. Sarah looked at me and said, “That’s the way people at the church I studied talk about racism—they talk about love.”

So we went back to our data. We pulled out our observational codes about love and race, and we found that we were hearing very similar discourse around racial inequality. The article theorizes the way that love becomes a sort of (White) racialized emotion through which racial inequality is upheld.

C.J. Pascoe is in the Department of Sociology at the University of Oregon. Her research focuses on young people, inequality, and education. Elena van Stee is a PhD student in the Department of Sociology at the University of Pennsylvania. She studies culture and inequality, focusing on social class, families, and the transition to adulthood.

Comments