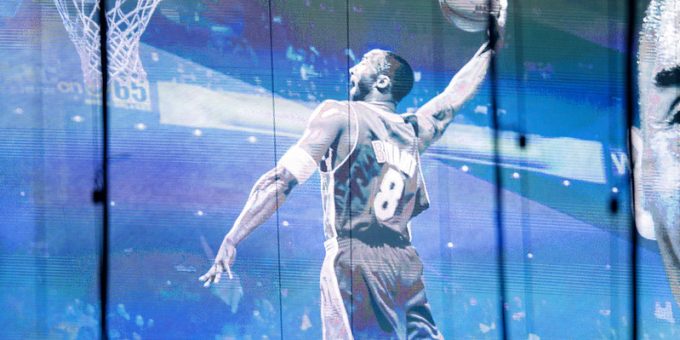

Image by Eric Drost, Flickr CC, https://flic.kr/p/2n6EBpK

And to Those Who Hath All-Star Nominations…

In 2016, Kobe Bryant was elected to the NBA All-Star game even though there were plenty of statistically better players. How could this happen?

In our study, recently published in the American Sociological Review, my co-authors Michael Kühhirt, Wim Van Lancker, and I argue that Bryant’s arguably undeserved All-Star nomination was an instance of the phenomenon that sociologists call “the Matthew effect.” This term references the Gospel of Matthew, which states:

“For unto everyone that hath shall be given, and he shall have abundance: but from him that hath not shall be taken away even that which he hath.” (Matthew 25:29, KJV)

In other words, success begets success. Or in this case, All-Star nominations beget All-Star nominations.

We used highly detailed data on all NBA players from 1983-2016 to show how people tend to confirm existing status hierarchies rather than rewarding the best-performing players. Specifically, we demonstrate that voters’ choices are biased by previous selections. Thus, a previous All-Star nomination improves a player’s chance of being nominated in future years. This means players without a previous All-Star nomination need to outplay others by a significant margin to overcome this disadvantage.

Sociologist Robert Merton’s seminal work on the Matthew effect describes the mechanisms underlying this process of cumulative advantage. First, initial status signals determine the allocation of resources. Then, as those with higher initial status accrue resources, they can use those resources to further improve their productivity, which legitimates their status. The rich get richer.

Sociologists have documented such status advantages in various domains ranging from academia to product markets. The same mechanisms also arguably underlie persistent status hierarchies, including gender and racial/ethnic hierarchies.

Despite much sociological interest in Matthew effects, until recently we lacked a way to empirically test the full feedback loop Merton hypothesized (i.e., the full chain from initial status to confirmation of said status). In our study, we use the setting of annual NBA All-Star elections to analyze the full status-to-status loop and to show that the confirmation of status is not completely justified by actual productivity differences. We demonstrate that in addition to actual productivity differences, players also benefit from status-biased votes. The more previous nominations a player could show, the more positive bias they would receive from voters—a process we call cumulative status bias.

The advantage of the NBA setting is not only the repeated nature of the status assignment process, but, uniquely, the detailed productivity measures we could use. We downloaded statistical information for every game played by each player from Basketball-Reference.com (check it out!). Due to data limitations, we focused on the years between 1983–2016.

Using this data, we ran a series of models assessing whether a previous election increased a player’s chances of election in subsequent years, adjusting for performance indicators before the previous election. And we found that it did. In fact, we found a total status advantage—a Matthew effect—of almost 5 percentage points. Given that the unconditional chance of becoming an All-Star is about 5% (24 spots for ~450 players), this is a significant move of the needle. Further analyses demonstrate that this Matthew effect is only partially explained by improved productivity after an All-Star nomination. Voters’ evaluations are also directly biased by a player’s prior status. Finally, we found that every additional previous nomination increases the chances over and above the immediately preceding nomination. Thus, there is cumulative status bias.What does it mean? Besides corroborating existing evidence on status advantages, our study shows that initial advantage feeds back into status hierarchies. Moreover, the decoupling of status and productivity potentially increases over time. This severely undermines meritocratic justifications of persistent status hierarchies.

We think that the NBA is a conservative test case for cumulative status bias for three reasons: (1) meritocratic ideals are relatively salient, (2) it is clear what productivity means, and (3) productivity is relatively easy to observe for voters. This suggests that the decoupling between status and productivity is potentially more severe in other domains, such as product markets or (brace yourself) academia. Moreover, this process is likely to reinforce broader structures of inequality, including racial/ethnic and gender hierarchies. In other domains, the intersections of achieved and ascribed status signals make the meritocratic allocation of resources extremely difficult. But if cumulative status bias helped Kobe Bryant obtain an 18th All-Star nomination, we expect to see even greater effects in everyday life, where the “points” are more often contested and hidden.

Read the full article here.

Find our data and code here.

Thomas Biegert is in the Social Policy Department at the London School of Economics and Political Science. He researches labor market inequalities, underlying mechanisms, and how they relate to institutional contexts.

Comments