Photo by Jo Jakeman, Flickr CC. flic.kr/p/4H77Gq

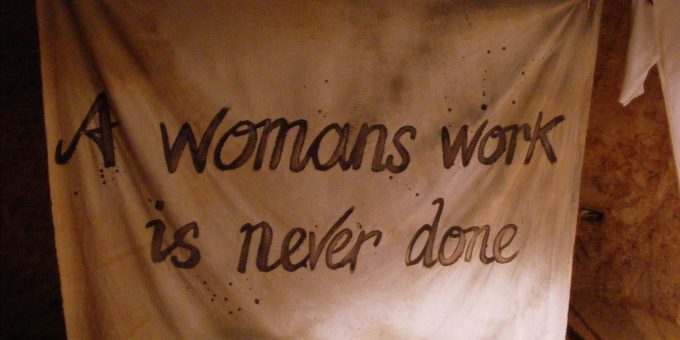

The Onus Is on Us—And It Shouldn’t Be.

“There’s a special place in hell for women who don’t help other women,” said the first female U.S. Secretary of State, Madeleine Albright, commenting on sexism and the American workforce. Expanding on this oft-repeated quote in an interview with feminist writer Marianne Schnall, Albright added that she meant women were “only strengthened if there are more women” active in their fields. But the quote, emblazoned on protest signs and pithy tote bags, retains a pair of implicit critiques: first, that women—at least some women, some of the time—are regularly witnessing the victimization and harassment of other women and coolly choosing to do nothing. Second, that high-achieving women are actually failing, in that they routinely refuse to help other women up the ladder and decline to use their social capital to make lasting change in organizations big and small. More simply, Albright’s quote can be read as a feminist rallying cry, as well as victim-blaming. It can also reinforce the idea that women are responsible for correcting the structures that create gender inequalities. That women are to blame.

Systemic inequality is buoyed by the idea that the underclass—whether they are women or a disadvantaged racial/ethnic group or economic class—holds the greatest responsibility for correcting inequalities. The problem of the underclass receiving the bill for solidarity applies basically anywhere we find a recognizable, lesser privileged group. Whether or not Albright intended to do so, her enduring words reveal just how steep those bills can be.Women already pay the costs of injustice—by receiving less pay for equal work, by surviving sexual assaults and sexual harassment at high rates (or worse, not surviving), by being passed over for male colleagues, by performing unpaid parenting labor disproportionately, and so on—and yet we as women demand even more labor of each other in the form of solidarity. We expect other women to be beacons of support, an obligation we reserve for each other, rather than for men and male allies. As members of this underclass, women are asked to do our jobs (generally at a gendered “discount”), to do the emotional labor of living with sexism, and to do the work of solidarity and redress.

Why is this an unsolvable problem? Should we not practice solidarity with one another? Should we not insist that we shoulder burdens in support of one another as members of an oppressed class?

I want to share a microcosmic success story in nurturing allyship—yes, another form of labor, this time enacted within my own marriage.

During the pandemic, like many other couples, my husband and I struggled with changes to our child’s school life and general routines. Soon I learned that my husband and I are much more normative when it comes to gendered labor than I’d ever noticed. Because of school closures, and Zoom school, my responsibilities as the household manager and default primary parent increased. (It’s the sort of thing made plain by feminist comic Emma in “You Should’ve Asked” and in her book, The Mental Load, blurbed with the telling comment, “a book to slip on all your colleagues’ desks.”) If I needed protected work time, I realized, it was my job to arrange childcare. It was always my job to broker labor related to our little one. And it was making me, well, angry. But a breakdown in communication led to a breakthrough: I was able to lay out the inequalities laid bare by the pandemic’s unusual circumstances and effect a major shift in the behavior of my own “upper class of one.” Since, my husband has shared more equally in parenting labor, whether it’s communicating with schools or sorting out who’s in charge when. He asks, “Would it be helpful if I did x?” I’m still in the position of household manager, but now I know I’m not the only one who knows it.

Women cannot be held responsible for all the labor of supporting one another, nor can we demand sisterhood of each other. There is continued labor in nurturing allyship, to be sure, yet my hope is that there are far greater gains to be realized from systemic change. Returning to Albright’s quote, I am even more resolved: I refuse to hold women more accountable than men in working for gender equality. Though I am grateful for Albright’s historic diplomacy and modeling of female leadership, this woman will not support the passing of the bill for solidarity to any underclass.Michelle Mueller is an IRB administrator for the California Institute of Integral Studies. She is the author of New Religions and the Mediation of Non-Monogamy: Polyamory, Polygamy, and Reality Television.

Recommended Readings

Madeleine Albright and Bill Woodward. Hell and Other Destinations: A 21st-Century Memoir. New York: HarperCollins, 2020.

Emma. The Mental Load: A Feminist Comic. Translated from the French by Una Dimitrijevic. New York: Seven Stories Press, 2018.

Gemma Hartley. 2018. Fed Up: Emotional Labor, Women, and the Way Forward. New York: HarperCollins.

Brad Johnson and David G. Smith. 2019. Athena Rising: How and Why Men Should Mentor Women. Brighton, MA: Harvard Business Review Press.

Comments 1

suika game

December 13, 2023Recognizing that expecting all women to carry the weight of supporting each other can be unfair and unsustainable, especially in systems that already place disproportionate burdens on women.