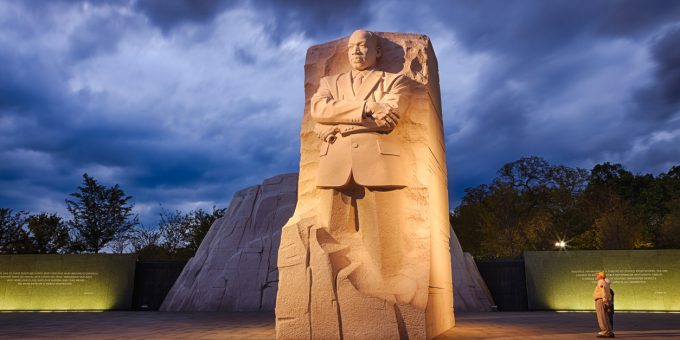

iStockPhoto.com // hanusst

The Struggle for Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Memory

In the video below,

The Struggle for Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Memory

In the wake of the racial justice uprisings of 2020, right-wing backlash instigated a powerful moral panic around racial education. Across the United States, state governments and school districts have since institutionalized legislation to limit and even prevent altogether instruction on the complex truths of the racial past.

Counterintuitively, some right-wing strategists have sought public support for these restrictions by leveraging a powerful symbol of the Civil Rights Movement: Martin Luther King, Jr. In fact, according to a 2021 analysis by NPR, during a Republican news conference addressing the alleged threat of critical race theory (CRT) in schools, half of the conservative speakers deployed Dr. King’s (decontextualized) expression of a “desire to be judged ‘by the content of their character, not the color of their skin.’”

Despite Dr. King’s long-documented struggle for critical education, he has now been weaponized against this very cause. How did we get here?

My book, The Struggle for the People’s King: How Politics Transforms the Memory of the Civil Rights Movement, reveals that contemporary political misappropriations of Dr. King are not new, nor anomalous. Tracing forty years of the political uses (and misuses) of the memory of Dr. King and the Civil Rights Movement, I show how groups with divergent—even oppositional—aims have strategically leveraged this collective memory. And I argue that these misuses of Dr. King’s legacy have devastating consequences for multicultural democracy, rolling back civil rights and criminalizing dissent.

My book, The Struggle for the People’s King: How Politics Transforms the Memory of the Civil Rights Movement, reveals that contemporary political misappropriations of Dr. King are not new, nor anomalous. Tracing forty years of the political uses (and misuses) of the memory of Dr. King and the Civil Rights Movement, I show how groups with divergent—even oppositional—aims have strategically leveraged this collective memory. And I argue that these misuses of Dr. King’s legacy have devastating consequences for multicultural democracy, rolling back civil rights and criminalizing dissent.

In honor of this year’s Martin Luther King Jr. Day, I’m excited to share a few central insights from this research. First, I want readers to understand that the political misuses of Dr. King are not accidents. They are intentional political strategies. Political distortions of Dr. King’s legacy date back to battles around the proposed King national holiday in the late 1970s and early 1980s when—after years of contention—then-president Ronald Reagan signed a bill designating the third Monday in January as a national holiday. Though this was ostensibly a progressive act, in reality Reagan despised Dr. King, opposed the gains of the Civil Rights Movement, and assured allies behind closed doors that the nation would remember a selective version of King, one that emphasized colorblind individualism and American exceptionalism.

As Reagan declared just before signing the holiday into law, “Dr. King had awakened something strong and true, a sense that true justice must be colorblind… As a democratic people, we can take pride in the knowledge that we Americans recognized a grave injustice and took action to correct it. And we should remember that in far too many countries, people like Dr. King never have the opportunity to speak out at all.”

This hijacked Dr. King would be whitewashed and co-opted to conjure a safe image of a beloved moral figure—one who had achieved his colorblind dream for America and made racism a mere artifact of the past. And indeed, this sanitized interpretation of King’s memory became a powerful political tool for a variety of right-wing social movements throughout the 1980s. Gun rights activists called themselves the new Rosa Parks, anti-abortion activists declared themselves freedom riders, and anti-gay groups claimed themselves protectors of Dr. King’s Christian vision. Conspicuously absent from these narratives were Dr. King’s statements decrying what he viewed as the three major evils of American society: racism, capitalism, and militarism. The radical King had been stricken from the record.I argue that these misuses of Dr. King are concerning not only because they are historically inaccurate but also because they provide fuel for right-wing movements. Looking to more recent examples, right-wing politicians have drawn on this alternative history to claim that Dr. King would have opposed contemporary racial justice movements like Black Lives Matter. They’ve argued that King would oppose affirmative action on the basis that it is “racist against White people.” And they maintain that King would oppose anti-war protests even though these protests often use disruptive tactics drawn directly from the Civil Rights Movement’s playbook.

These strategies provided fuel for what we now know as “Great Replacement Theory,” the far-right conspiracy theory, amplified by public figures like Tucker Carlson on Fox News, that posits White people are being demographically and culturally replaced with non-White individuals and that White existence itself is under threat. This type of historical revisionism played a key role in the 2016 election of Donald Trump, providing a foundation for his administration to ban anti-racism trainings and roll back civil rights. It emboldened White supremacists toward violent ends, including the insurrection of the Capitol on January 6th.Although I’ve painted a bleak portrait thus far, I want to leave readers with a final insight from The Struggle for the People’s King that gives me hope during what feels like an impossible societal impasse. In my research, I discovered that activists advocating for immigrant and Muslim rights experienced moments of revelation and transformation in drawing parallels between the Black freedom struggle and their own efforts. These reflections resemble the practice of developing a sociological imagination, learning to interpret our own experiences within a broader social context and a longer history that reveals our underlying human connection across boundaries, borders, and time.

In turn, this recognition of anti-Blackness within immigrant communities can facilitate the development of genuine solidarities with Black Americans. In this way, collective memory becomes a bridge to unite communities in linked fate, or, as King himself once described it, the “inescapable web of mutuality.” Yet such alliances do not emerge overnight. They require the slow, relational work of spending time in community with one another, listening and learning, and building trust—all practices that are foundational elements of the Civil Rights Movement.

The Struggle for the People’s King is not just about the dangers of revisionist history. It is also about how people’s histories, beyond the mythologized “Kings,” can expand our imagined futures and our resolve for bringing them to fruition.As Dr. King said, “Now let us rededicate ourselves to the long and bitter, but beautiful, struggle for a new world.”

Hajar Yazdiha is in the Department of Sociology at the University of Southern California. She is author of The Struggle for the People’s King: How Politics Transforms the Memory of the Civil Rights Movement.

Comments