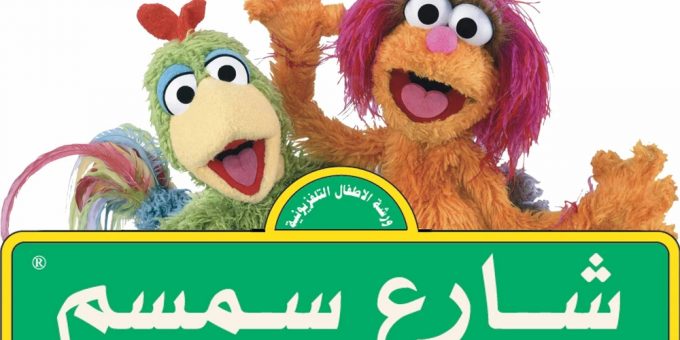

Kareem and Haneen star in the Palestinian version of Sesame Street. MuppetWiki.

A Sesame Street Feat

When we think about the spread of American culture, we might picture someone eating a Big Mac in Bangladesh, listening to Bruce Springsteen in Singapore, or watching a Disney movie in Denmark. This process, often referred to as Americanization, involves the top-down export of distinctly American products to other countries. But, as Tamara Kay shows in her new Theory and Society article, culture can also spread through more synergistic processes between American distributors and local cultural producers.

The beloved children’s program Sesame Street, which now exists in over 50 countries around the world, is a prime example. Rather than simply air the American version abroad, Sesame Works, the company’s non-profit arm overseeing global diffusion, endeavors to co-produce localized versions of the show that mix its core values of tolerance, nonviolence, and equality with culturally resonant characters and narratives. For example, instead of Big Bird and Elmo, children in Palestine learn cultural pride from Kareem, a seven-year-old green rooster, whose friend Haneen is a vivacious, furry champion of women’s empowerment.Kay spent nearly a decade observing how representatives from Sesame Works interacted with and exchanged cultural knowledge with partner organizations to develop localized programming. She also conducted 140 interviews with key personnel. From this data, she identified two distinct processes that enable the successful co-production of global Sesame Streets. First, partner organizations and staff from Sesame Works align their interests around mutually supported values by putting forward their non-negotiables and identifying shared goals. Second, both groups deliberately and iteratively exchange complex cultural knowledge—think more abstract values and norms, like fairness, that require nuanced discussion to communicate—to make a hybrid version of Sesame Street that reflects the core values of the original in culturally relevant ways.

The success of Sesame Street’s global adaptations is particularly remarkable considering that its proliferation occurred during an era of heightened cultural polarization. By examining the interactional processes underlying this success, Kay’s study illuminates an alternative—and more equitable—model of globalization in which new cultural products are co-constructed across national boundaries. Once again, Sesame Street has taught us something about how to get along.