Shifts in American media portrayals of Chinese student migrants map onto historical changes in the relationship between the two countries over the past four decades. iStockPhoto.com // goc

Changing Faces: The Shifting Image of Chinese Student Migrants in American Media

Do you remember the headlines from the 1980s featuring courageous Chinese students fighting for democracy in Tiananmen Square? Fast forward a couple of decades and these images have all but disappeared from American news media. What changed?

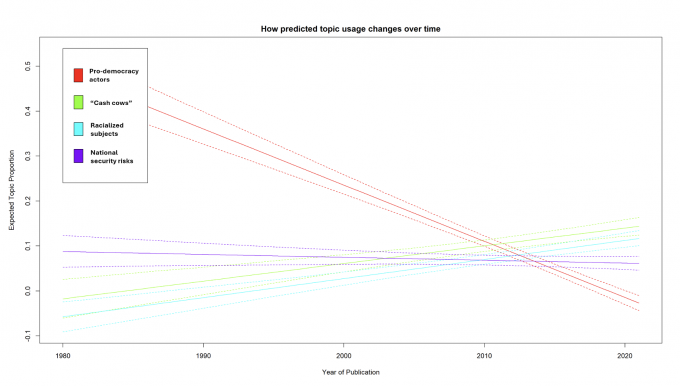

I set out to answer this question through computational text analysis. Analyzing more than 1,500 American news articles spanning four decades, I uncovered a significant shift in the portrayal of Chinese student migrants by U.S. news media. Once depicted as pro-democracy heroes who sought political asylum in the United States, Chinese student migrants now tend to be portrayed through a lens of economic opportunism, racialization, and political suspicion. This shift maps onto broader historical changes in the relationship between the two countries over this period.Punctuated by the Tiananmen Square Protests, the 1980s largely saw Chinese student migrants celebrated as champions of democracy in American news media. Over time, however, this narrative faded. Starting in the 2000s, Chinese student migrants began to be discussed as a lucrative source of “tuition dollars” for American education and were increasingly valued for their financial contributions to the U.S. economy.

The media also increasingly portrayed these students through the racialized lens of the unassimilable “perpetual foreigner” stereotype. This narrative was aggravated by the COVID-19 pandemic, during which Chinese student migrants were unfairly stereotyped as virus carriers and spreaders.

Further, these students are frequently depicted as potential national security risks, with accusations reminiscent of Cold War-era paranoia. Sensational news articles accusing Chinese student groups on U.S. campuses of receiving money from the Chinese government or that Chinese students are engaging in academic and technological espionage are rampant. I found that this national security narrative has been the most persistent over the past four decades. A recent study suggests that it has contributed to a chilling effect among Chinese American researchers.

This shift in American media portrayals of Chinese student migrants maps onto historical changes in the relationship between the two countries over the past four decades. My analysis suggests that as China’s influence on the global stage has expanded, so too has the inclination to view its overseas citizens with skepticism and apprehension. More and more, Chinese students are not regarded as having individual political agency; they are seen, rather, as extensions of the Chinese government. Thus, whether Chinese students are construed positively as economic assets or negatively as threats to national security, contemporary discourse ultimately reinforces a persistent, essentialist view of China as “Other,” characterizing the country as a totalitarian regime fundamentally at odds with liberal democracies.

This shift in American media portrayals of Chinese student migrants maps onto historical changes in the relationship between the two countries over the past four decades. My analysis suggests that as China’s influence on the global stage has expanded, so too has the inclination to view its overseas citizens with skepticism and apprehension. More and more, Chinese students are not regarded as having individual political agency; they are seen, rather, as extensions of the Chinese government. Thus, whether Chinese students are construed positively as economic assets or negatively as threats to national security, contemporary discourse ultimately reinforces a persistent, essentialist view of China as “Other,” characterizing the country as a totalitarian regime fundamentally at odds with liberal democracies.

The changing narratives illustrated here should prompt critical reflection on the impact of media framings on our perception of Chinese student migrants and, by extension, the nation they hail from. They highlight the need for a deeper, more nuanced understanding of the diverse roles and identities of Chinese students in the United States—beyond the headlines, to the heart of their lived experiences and contributions. These students’ individual stories, ambitions, dilemmas, and struggles merit acknowledgment beyond their perceived economic utility or their country’s political agenda.

Weirong Guo is a postdoctoral fellow in the Asian American Studies Program at the University of Pennsylvania. She studies culture, politics, and Chinese diasporas with a focus on Chinese student migrants.