iStockPhoto // BrianAJackson

The Gender of Inheritance: The curious case of the early 20th-century Dallas elite

We are on the verge of one of the biggest wealth transfers in world history—what some social scientists have called “The Great Wealth Transfer.” We are also living through a huge increase in wealth inequality. Yet we know surprisingly little about a key type of wealth transfer: inheritance. What do people actually do with their wealth when they die?

In a new study published in Socio-Economic Review, I meticulously trace the inheritance practices within a specific wealthy population—the White upper class of Dallas, Texas—from 1895 to 1945. To do this, I linked bequest data to a kinship network I constructed using the Dallas social registers and other archival sources. I also analyzed qualitative data, including memoirs, oral histories, and the wills themselves.

I began by asking a simple descriptive question: Who inherited what? Based on what I already knew about this population (it was super patriarchal) and everything I’d read about inheritance practices among the wealthy (they typically favor sons), I expected to find that men inherited more than women. This is a very common “family wealth arrangement” in a global-historical context. It’s even the case in supposedly gender-equitable legal contexts like France and Germany.

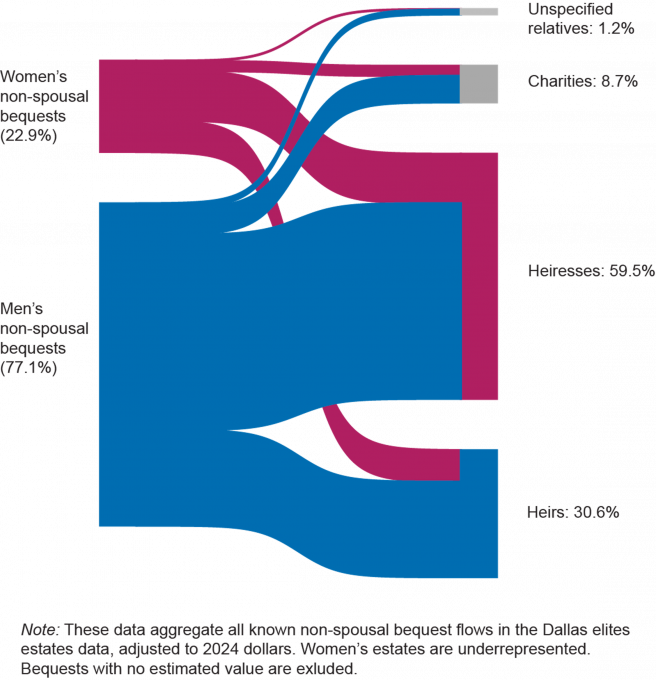

But the Dallas data revealed a surprising pattern. The figure below illustrates that, overall, women inherited triple what men did. It wasn’t even close. Even when I exclude bequests between spouses, which overwhelmingly went to wives (who tend to outlive their husbands), women still inherited twice as much as men.

What on earth was going on? That’s a question for the qualitative data. As it turns out, there was a general social expectation that if elites died with any financially vulnerable, socially recognized close kin, those heirs would receive extra bequests. That mostly meant husbandless women and fatherless children. It was a kind of private, gendered safety net approach to distributing fortunes at death. This expectation was so strong that one local banker, Buckner McKinney, felt the need to explain in his will why he was not leaving an extra bequest to his unmarried sister Hallie—she was already quite rich.

Of course, this interpretation is based on the convenient fiction that fortunes are fungible—in other words, that we can simply count the dollar value of each person’s inheritances, divide them up by gender, and call it a day. Yet a deeper look at the data shows that men and women inherited different forms of wealth. Men inherited properties that gave them opportunities for accumulation and control, like stocks and trusteeships. Women inherited the kinds of wealth that gave them status and stability, like mansions, trusts, and jewelry. We can think of this as a gendered family system: men were matched to properties that enabled them to get even richer, and women were matched to properties that helped them maintain their family class status—without giving them significant economic control.The findings from my study offer two key takeaways. First, we still need a lot more information about variations in gendered inheritance practices among the wealthy. What other gendered inheritance practices are out there? How do those practices influence the distribution of wealth across gender categories and the population more generally? And how do they influence the relative stickiness of wealth across generations? Second, even in extremely patriarchal contexts, understanding inheritance and class persistence requires us to pay attention to women.

Shay O’Brien is a postdoctoral scholar in the Stone Program in Wealth Distribution, Inequality, and Social Policy at Harvard. She studies elite kinship networks.