Finding Culinary Injustice

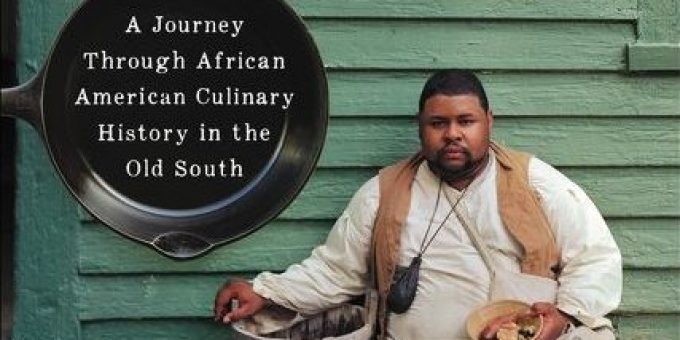

The Cooking Gene: A Journey through African American Culinary History in the Old South

By Michael W. Twitty

Amistad Press, 2017

464 pages

Television shows, books, magazines, and countless social media posts take an omnipresent object—food—and center it as a matter of conversation, concern, and capital. Despite the prevalence of a foodie subculture and quests for new and exotic food experiences, thinking about food should also prompt us to consider social issues like childhood hunger and obesity. Access and affordability differentially shape what (if anything) appears on people’s plates, especially in urban and rural areas where it is often difficult to find a grocery store. Michael Twitty’s The Cooking Gene presents a unique account of how foodways (cultural, economic, and social practices tied to the production and consumption of food), race, identity, and history intertwine, helping us understand food, and our fascination with it, today. In it, Twitty satisfies our hunger for the history of Southern food culture while also addressing the substantial problems of malnourishment, obesity, and their relation to identity among those historically oppressed groups most likely to experience the negative consequences of not having enough healthy food options. Further, Twitty calls for culinary justice through conversations, awareness, and ceding space in light of past exploitations.

Part memoir, part history lesson, and part cookbook, Twitty’s book tells us that his early experiences around food left him feeling disconnected from his race, culture, and its foodways. Over time, he realized “[a]ll self-hatred is nonsense, and it’s a sickness only your soul food can cure” (26). Food could be a salve for social ills, feeding a hunger for connection to the past and to each other. Throughout the volume, Twitty devotes considerable time to exploring his genealogy, using his ties to Africa and the Southern United States to construct and connect this emerging identity to further modern foodways and cross-cultural understanding.

The politicization of food and foodways is a continual undercurrent of race and genealogy discussions. Although considerable space is devoted to the importance of genealogy for African American identity, Twitty presents important elaborations on the connections between food and power, specifically health, gardens, accessibility, and debates of authenticity. As he notes, “[w]e have come to this strange cultural moment where food is both tool and weapon” (403). This statement bridges the past, present, and future for considering how important food is as a tool of resistance and understanding. In this sense, food can become a reconciliation project for history and identity. And from these conversations, Twitty is able to reveal insights into current debates regarding the social problems of health disparities.

Twitty’s is a straightforward yet hard-hitting argument about the intertwined inequalities of foodways, culture, and health: the next human rights abuse, he writes, is rooted in nutrition, access, price, and heritage. In a world filled with consumer products marketing themselves as timesavers in the kitchen, processed foods have replaced heritage foods, stripping away the unique identity embedded in authentic food. Historically dominant ingredients in the African diet, such as collard greens and fresh seafood, are displaced through the Western emphasis on fried and fast foods, and that has drastic, racialized health consequences. These shifts in food culture have also buoyed stereotypes of Southern and soul food (and those who love them) as unhealthy. These cultural views are not new, nor are the battles chefs, particularly chefs of color, have waged to dispel these beliefs about their communities, cultures, and foodways.

Twitty introduces us to chefs such as Bryant Terry, who concentrates on vegan soul food, who focus their careers on combatting the health problems linked to soul food by transforming recipes and maintaining their flavor and connections to the past. Other chefs in this volume focus on gardens as a site of resistance and solutions to modern health problems. Historically, gardens were a source of safety and security, because they ensured an affordable food supply throughout the year, especially in times of poverty or instability, but urbanization pushed gardening and ecological knowledge to the past. Safety and security were soon replaced with hunger and food desserts. The urban gardening movement, while not without important gender critiques, has brought gardening and healthy food to children in major urban areas, such as Will Allen’s celebrated Milwaukee project. African American chefs, farmers, and children furthering the Black food movement, with its emphasis on access and equality, dominate many urban gardens and make it clear that they are sowing resistance by teaching subsequent generations lessons about cultural history and identity that may otherwise be lost to the McDonaldization of foodways. Better still, those generations will reap the rewards of access to healthy nutritious food and the knowledge of how to grow and prepare it.

Resistance also occurs in healthy diets, gardening, and leadership. However, progress toward healthy, accessible, and affordable food must combat problems relating to claims of authenticity and awareness of past appropriations. While “healthy Southern food” is often seen as an anomaly in a cuisine associated with butter and deep-frying, chefs are working to dispel this image in favor of fresh seasonal food. Elite chefs sell “authentic” versions of Southern cuisine, rooted in historically accurate ingredients such as Carolina Gold Rice leading to the increasing popularity of reconstructions of the South as a legitimate source of food culture. For example, the cooking competition show Top Chef made Charleston, South Carolina the site of its fourteenth season. Episode after episode, viewers were presented with a purportedly authentic journey into Southern foodways and local history. In one episode, the chef-testants recreated the celebrated cuisine of Edna Lewis, a Black, female chef raised in Virginia, who made her career in New York City, then returned as the celebrated chef of Middleton Place. Lewis’s cuisine calls stereotypes about Southern food sharply into question as the competitors emphasize fresh, seasonal ingredients and heritage foods made from scratch. Even our ideas of what a cuisine “is” must be questioned; those ideas have been socially constructed, flavored with different eras’ stratification and inequality, food fads and social closure.

After Season 14 of Top Chef aired, Lewis’ cookbook rose to the number five spot on the Amazon bestseller list. Why would it take a culinary competition show to shed light on one of the most influential chefs elevating Southern food and African American culinary experiences beyond the stereotypes? Twitty publicly engages this question through his interactions with and writings about prominent Southern chefs such as Sean Brock and Paula Deen. Although today he and Brock have seemingly resolved their disagreements and plan to discuss the relationship between Southern food and appropriation, the erasure, or “culinary injustice” as Twitty calls it, of slaves and their role in Southern food is a continuing problem in food circles. There is still a long way to go toward ridding society of culinary injustice, but leading culinary figures such as Twitty, Brock, John T. Edge, and Tunde Wey are taking steps to “share” space, or move toward reconciliation. Their ongoing conversations raise awareness about culinary injustice and the associated problems of health and hunger across generations.

As readers follow Twitty’s quest to find balance in his heritage, food, and identity, he emphasizes the unparalleled importance of authenticity as a tool for understanding culture. “Let me taste the one and only true Jollof rice, red with tomato and palm oil, spiked with ‘the truth’” (415). Although recipes evolve over time with the migration of people and ingredients, the relationship between heritage and authenticity remains essential for coming to terms with modern injustices. Consider one of the most celebrated foods in the U.S.: barbeque. With its many regional variations on styles and sauces, barbecue’s origins are often contested (despite resounding evidence that the Taino in the Caribbean and enslaved people in the South were largely responsible for barbecue’s preparation as it appeared in the Americas). The construction of “authentic barbecue” becomes a way for today’s communities to understand a piece of their shared past, but if it is to become a source of inspiration and understanding, rather than exploitation, appropriation, and erasure, even the tastiest pork should come with a side of origin stories. This is hard, to be sure. Food isn’t like art, where a piece can remain in its original form for centuries; food has a short lifespan, disappearing as soon as it is consumed or spoils. Oral histories and recipes passed down through families become the main source of modern authentic foodways, but these connections can only last if the foodways are deemed culturally relevant within a family, otherwise they can be lost to memory. Food knowledge and culture are highly vulnerable: they can become lost across centuries of erasure and appropriation, replaced by diets steeped in refined sugars and processed foods. So often, they have been.

The Cooking Gene contributes to a timely conversation about the importance of food from the standpoints of both health and heritage, particularly furthering discussions on the role of Southern food in addressing modern social problems. Southern food is not a new site of resistance or discussion. Indeed, southern food has been used to further social causes for decades, including at the height of the Civil Rights Movement, and bringing people together around food helps facilitate discussions about difficult social issues. Twitty’s experience with the culinary history of the South allows the reader to take an intriguing journey through the past—where solutions to modern problems of hunger, obesity, and heritage can be found.