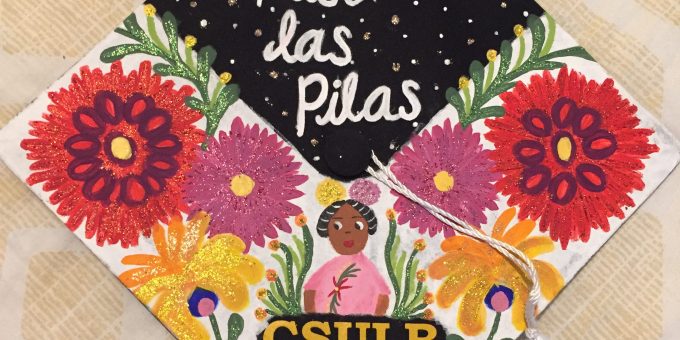

“[T]he quote ‘me puse las pilas’ is a phrase that in English literally translates to ‘I put the batteries on myself’ but in Spanish it means so much more. My parents always said ‘ponte las pilas’ when I was slacking or when I wasn’t applying my full potential... My quote is a response to that phrase saying that I’m getting my life together, one degree at a time.”

Higher Ed Can Learn From First-Gen Students

The first-gen experience is all about precarity. As a first-gen college student and first-gen advocate, I know.

Unlike our continuing-gen peers, first-gen students don’t necessarily grow up expecting to attend college. Our path to higher education is contingent on moments of connection with academic material and mentors as well as the absence of some of the obstacles that could set us on a different track. Each “next goal” for the first-gen college student is the same: a bachelor’s, a PhD, or tenure is never assured.

Research ties this precarity to “impostor syndrome,” or the fear of being “found out” as not belonging in institutions designed to serve others with more privilege. In response, institutional mentors seeking to support first-gen students try to provide material and cultural resources that will allow us to “pass” among our continuing-gen peers. These efforts make sense in the short term, but initiatives based on this approach are ultimately conservative. They require first-gen students to adapt to institutions rather than requiring institutions to adapt to better serve first-gen students.

The first-gen label necessarily encompasses diverse identities including race, class, gender, and sexuality and diverse experiences of schooling, work, criminal justice, and military service. Yet first-gen works here as a social category because it pertains so directly to the mission of higher education to cultivate talent, provide economic opportunity, and enable civic engagement. The educational disparities between continuing-gen and first-gen students indicate a failure to carry out this mission.

This is to say, the first-gen standpoint provides a critical lens through which we can reflect back on institutions of higher learning. First-gen students see through the myth of meritocracy; our social location makes us witnesses to both the triumphs of privileged mediocrity and the struggles of marginalized excellence. First-gen students can see exactly how the deck is stacked.

My own sociological research with high school teachers indicates that transformative practices cannot simply be the product of individual ideals. Change will depend on the development of organizational resources that enable actors to work together to re-frame dominant discourses. My experiences in first-gen advocacy have often brought me into close contact with well-intentioned institutional actors who nevertheless enact a conservative approach to first-gen support. For example, an admissions officer advised the college access nonprofit where I worked, “Don’t send us too many low-income -Latinas,” because they would compete for the same slots. A first-gen advisory committee meeting I attended in law school saw student participants effectively silenced because their time was used, instead, by faculty touting their own first-gen status or their mentorship of first-gen students.

I am made hopeful by the American Sociological Association’s commitment of organizational resources to the project of serving first-gen and working-class students through the development of a task force. Though larger social movements and political-economic changes are necessary to resolve class disparities within higher education, a discipline can make headway.

A recent survey by ASA researchers John Curtis and Nicole Amaya shows that only 21.4% of ASA members have parents with no educational attainment after high school. Improving this statistic—including more first-gen folks among the ranks of sociologists—will require action on multiple levels. Teaching undergraduates, sociologists will need to both de-mystify academic careers and connect sociology to other career tracks in public service, nonprofits, and business. In graduate admissions, sociologists will need to consider varied life experiences and innovative thinking as assets worthy of at least as much weight as rationalized measures like GPA, institutional ranking, and GRE scores. As advisors and colleagues, sociologists must stop valorizing the detached research position to instead celebrate and cultivate first-gen sociologists’ engagement with communities and our abilities to adapt and code-switch. Sociologists must examine their classed rubrics for personal comportment and their classed expectations for work-life balance—and do all this with the same rigor they apply to their research.

Centering first-gen students’ assets will disrupt disciplinary norms that provide the basis for departmental status and individual reputation. This work will be disorienting for many. But truly transformative advocacy does not seek to stabilize first-gen students’ trajectories; it requires those with privilege to step into precarity so as to amplify all our trajectories together.

Comments 1

prediksi sgp

November 11, 2018I like this blog.

prediksi togel terjitu