Literacy Through Photography

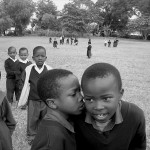

Artists, activists, and teachers around the world have put cameras into the hands of children, asking and allowing them to share their visions and stories. The resulting images are illuminating and the experience is memorable, if often fleeting.

Literacy Through Photography is a student-centered critical pedagogy that integrates writing and photography into classroom instruction. Developed by the artist and educator Wendy Ewald at Duke University’s Center for Documentary Studies, LTP has collaborated with the Durham public school system for 20 years, and for the last decade has been a teacher-training program for educators from across the U.S. and abroad. Since 2008, a small staff from CDS and a rotating group of Duke University student fellows sponsored by DukeEngage have spent each summer in Tanzania, first training local teachers in LTP’s methods and then assisting in the development and teaching of classroom-based LTP projects.

The LTP program in Tanzania aspires to make an impression on children while working more broadly to influence ways of learning and styles of pedagogy within Tanzanian schools. The work begins not with children, but with the teachers who once studied in traditional classrooms based on rote memorization and are now charged by the Tanzanian government with a shift toward participatory methods of instruction.

Whether in North Carolina or in Tanzania, any LTP activity—whether “reading” a photograph, brainstorming how to represent conceptual ideas visually, framing and shooting photographs, or writing creative stories or narrative descriptions about pictures—emphasizes critical thinking as well as visual, cultural, and written literacy. Drawing on many years of experience, the Duke staff and students learn alongside the Tanzanian teachers and students. Together they continue to recognize the meaning, potential, and challenges of LTP in Tanzania in light of restricted resources, class sizes that reach 100 children, strict national curricula, and educational reform efforts.

In addition to managing logistical hurdles, the Duke staff are discovering how to navigate differing priorities and even assumptions about photography. Does it show the “real thing”? Are photographs open to interpretation? And how should photography be folded into a lesson plan? A Durham teacher, for instance, might emphasize self-expression, assigning students to create a self-portrait in a language arts class. But a Tanzanian teacher might ask students to illustrate specific English or Swahili verbs, accomplishing both a process-oriented goal—a grammar lesson—and a product-oriented goal—the creation of prints to be used as visual classroom aides, which are noticeably missing in most Tanzanian schools.

LTP has trained over 150 teachers from 45 primary and secondary schools and several teachers’ colleges in Tanzania, and well over 2,000 Tanzanian children have participated in school-based LTP projects. To foster the program’s sustainability, the LTP Teacher Resource Center has been established to house a growing collection of cameras, printers, and other photography supplies. The LTP program abroad continues year-round under the leadership of a Tanzanian teacher and artist and with the counsel of a local advisory committee comprised of experienced LTP teachers. These teachers recognize that not all students learn by one method, so photography and the LTP program can open up opportunities for shy or less eloquent students to participate in learning. One teacher says he feels that East Africans often turn a blind eye to students, but LTP opens up a new educational opportunity. As his fellow teacher put it, the best thing about LTP is how it allows teachers to see how their students see—and how they imagine.