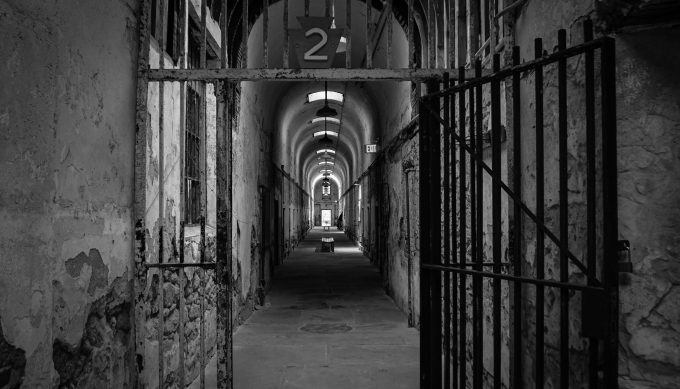

A guide leads a group of international visitors through the west wing of Kilmainham Gaol. Leaders of the 1916 Rebellion were held here prior to their executions. Author photo, used with permission.

Prison Tourism in the Era of Mass Incarceration

In 2017, The World Travel Awards named Spike Island, a former fortress and prison located on the southern coast of Ireland, Europe’s leading tourist attraction. It is one of the most prestigious honors conferred by the travel and tourism industry. To win, Spike Island had to beat out noteworthy destinations like Buckingham Palace, the Eiffel Tower, and the Acropolis. Bestowing such an honor on a defunct prison appears, at first blush, a peculiar choice, but correctional facilities are inarguably popular among tourists.

The former federal penitentiary Alcatraz in San Francisco, California hosts over 1.5 million visitors annually, making it one of America’s top tourist attractions. And each year, over 50,000 people take a ferry from Cape Town to explore Robben Island, the South African prison compound where Nelson Mandela spent the majority of his 27-year sentence. In Cartagena, Columbia, visitors and locals flock to dine at Restaurante Interno, a restaurant housed within an operational women’s prison and staffed entirely by inmates. Tourists looking for an even more immediate experience can rent a cell in Het Arresthuis (“House Arrest”), a former prison turned luxury hotel located outside Amsterdam, Netherlands. What do tourists encounter when they visit carceral sites, which Michel Foucault once referred to as the “darkest region in the apparatus of justice?” Prison museums provide a glimpse into an institution that is both politically familiar and culturally enigmatic. And if this is the case, what exactly can they reveal to us about crime and punishment at different times and in different places?

Given the ubiquity of prisons in contemporary life, the emergence of penal tourism is not surprising. It has occurred in tandem with steady increases in the size of the global prison population, as well as the colossal expansion of the American prison system. Today, ten and a half million people are incarcerated worldwide, with nearly a quarter confined in the U.S. To investigate the ways prison museums approach the topics of crime and punishment and what this might suggest about mass incarceration, we recently visited two of the largest prison museums in the world—Eastern State Penitentiary in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and Kilmainham Gaol in Dublin, Ireland. Both sites devote considerable attention to the architecture of confinement and the physical conditions that incarcerated people endured. And both endeavor to humanize prisoners through creative use of audio recordings, letters, documents, and photographs. Despite these similarities, we discovered significant differences in how each site mobilizes historical artifacts, architectural space, and prisoner biographies to craft a broader account of the role of prisons in wider society.

Eastern State: The World’s First Penitentiary

On the approach to Eastern State Penitentiary, visitors are confronted by a massive, Gothic-inspired fortress whose creator, architect John Haviland, hoped would “strike fear into the hearts of those who thought of committing a crime.” When it opened in 1829, Eastern State was not only the world’s first penitentiary, but also the largest and most expensive building in the U.S. Unlike earlier prisons, where men, women, and children were often housed together in large, congregate rooms, Eastern State featured a system of solitary confinement in which prisoners were locked in single cells and barred from all forms of social interaction, including talking to one another across the cell block’s corridors. The goal of this “silent system” was to leverage architecture in the service of behavioral and spiritual change. Eastern State’s founders believed that physical and social isolation would prompt prisoners to reflect on their crimes and seek meaningful forms of redemption. So unique was the prison’s design and so ambitious its goals that it attracted over 10,000 visitors in its initial years of operation.

By the time the prison closed in 1971, its founders’ aspirations were long dead, collapsed under the weight of overcrowding, violence, and competing ideologies of punishment and reform. Today, museum-goers are invited to explore the contradictions of competing criminal justice ideologies. For example, visitors are encouraged to step into one of the tomb-like cells that make up the housing blocks. Inside the cell, the soundscape is muted so that even the noisy bustle of tour groups making their way through the hallways is dulled. It’s not hard to imagine how the space might facilitate sustained contemplation, but the audio tour reminds guests of the brutality that underscored the silent system. An actor enumerates the punishments that prisoners endured for breaking the rule of silence (e.g., gags, straight jackets, sensory deprivation, beatings, and restricted diets), while another reads a prisoner’s account of what it was like to live in isolation, “There is not one redeeming principle; there is but one step between the prisoner and insanity.”

As the tour proceeds, it becomes clear that in spite of its grim façade, soundless corridors, and torturous penalties for misbehavior, Eastern State had failed to appreciably reduce crime. This fact is not directly addressed on the audio tour or among the information placards that hang in the hallways, but it is revealed as visitors move through the oldest cellblocks to the more contemporary ones. In its original design, Eastern State was comprised of three cellblocks that held a total of 256 prisoners in single cells. Three years following its opening, four more cellblocks, with multiple tiers, were built to accommodate the growing tide of men and women sentenced to prison terms. Over the hundred years that followed, the prison expanded to include 15 cellblocks and over 1,700 prisoners. This begs the question, what were the historical, political, cultural, and economic forces that generated increases in the size of the prison’s population? How did these forces contribute to the persistence of incarceration as a response to crime and other social problems? On these questions, the museum is silent. In this silence, crime and punishment seem inevitable features of American life.

Kilmainham Gaol: The Bastille of Ireland

Like Eastern State, Kilmainham Gaol is situated just beyond city center, its presence announced by imposing stone walls. Opened in 1796, it has a smaller footprint than Eastern State. The original facility was comprised of two housing blocks situated on either side of a central administration building. It was the product of a reform movement lead by John Howard, an English philanthropist, who advocated for single-celling to enhance moral reform and improve the health of prisoners. The use of single cells here was not to encourage silent contemplation so much as it was to prevent prisoners from “corrupting” one another by sharing of criminal techniques. Unfortunately, overcrowding plagued the Gaol and undermined reform efforts from its early years until its closure in 1924. At various points, up to five men, women, and children were held in cells that were approximately 300 square feet.

The source of overcrowding is one of the predominant themes that tour guides discuss as they lead visitors first through a chapel and then into the dark, cramped quarters of the west wing. As visitors peer into the tiny cells, the guide explains that in 1840, 30 cells were added to alleviate the horrifying conditions that women endured. Why were so many women and children incarcerated? A register on display in a separate portion of the museum reveals pronounced increases in “food-related offenses.” Crime was largely a function of the conditions of extreme poverty triggered by Ireland’s Great Famine of 1845-1849. Visitors learn that nearly one million Irish starved to death during the Famine. Those who survived did so through any means necessary. One entry in the register reports that a boy was incarcerated for “attacking” a bread cart. As the tour guide explains, “hunger knows no law.”

This effort to contextualize the crimes of Kilmainham’s prisoners is visible throughout the museum. This is not the case in Eastern State, where the biographies of prisoners reference their crimes or their stints in prison with few additional details about their lives or the times in which they lived. In addition to poverty, Kilmainham’s museum also situates crime as a direct function of politics. The tour highlights how crucial historical moments in the life of the Gaol closely dovetail the ascent of Irish nationalism and efforts to create an independent nation state free from British rule. Virtually every nationalist leader in the struggle for Ireland’s independence had been incarcerated at Kilmainham Gaol, and many were executed. The museum, like the Irish state, celebrates these men and women as heroes. Their names, likenesses, and a number of their personal possessions ranging from gun holsters to love letters are displayed throughout. At the end of the tour, guides lead visitors to the “Stonebreakers Yard” where 14 nationalist leaders of the Easter Rising were executed in 1916. Their deaths are commemorated with a plaque, two crosses, and the Irish flag.

The Future of Incarceration

Recently, Eastern State mounted a new display in a corner of the prison yard. Called “Prisons Today,” it invites visitors to consider the escalation in the size of the nation’s contemporary prison population and whether certain crimes warrant a prison sentence. In this, there are faint echoes of the lessons of Kilmainham Gaol: that crime is ultimately a political designation and punishment is an exercise of state power. Although Ireland, like other European countries, has witnessed an increase in its prison population over the last several decades, it does not exhibit the same dependency on incarceration that characterizes criminal justice policy in the U.S. Perhaps one clue as to why is in how it memorializes its prisons.

Comments 1

g

November 10, 2018The country of COLOMBIA is misspelled.