When the U.S. Sneezes, Puerto Rico Already Has a Cold

“Cuando Estados Unidos estornuda, ya Puerto Rico tiene catarro”—“When the U.S. sneezes, Puerto Rico already has a cold.” This saying captures the relationship between Puerto Rico and the United States. The unequal and often contested relationship between the island and the continental U.S. is important to contextualize in order to understand the unfolding events from the impact of Hurricanes Irma and Maria. The sociological study of disasters has clearly suggested that while these hazards are natural occurrences, disasters are primarily caused by social, political, and economic conditions. This is clearly the case with Puerto Rico.

Puerto Rico’s problems are usually hidden or not viewed as critical to the average American. For instance, a recent poll found that only 47% of those interviewed knew Puerto Ricans are U.S. citizens by birth (Suffolk/USA Today 2017). For years, the economic conditions on the island have been deteriorating to a point that the Puerto Rican government had to default on some of their debts in order to remain afloat. Since the beginning of the 2006 recession, the Puerto Rican economy has shrunk and the island has lost over 270,000 jobs (20%) (Marxuach, 2015), decreasing the island’s tax base while deepening its debt. This debt weighs heavily over the island’s people; in fiscal year 2015, 16% of the consolidated budget was dedicated to debt service, while only a paltry 4.2% was committed to public improvements or investment. No wonder the power grid could not sustain Hurricane Irma, a category 5 storm that passed just north of the island, let alone Hurricane Maria, a category 4 (almost 5) storm that directly sliced the island leaving vast devastation in its wake.

As a territory of the U.S., Puerto Rico is not allowed the protections of bankruptcy that federal law allows to other states and jurisdictions. These economic conditions and U.S. government-imposed austerity measures have push island Puerto Ricans to the brink so that massive migration to the U.S. has been the solution for any who can afford to leave. Current out-migration figures are greater than ever before—between 2005 and 2015, 446,000 Puerto Ricans moved from the island to the U.S. mainland (Krogstad et al., 2017). In 2014 alone, 84,000 Puerto Ricans transplanted to the mainland, a 38% increase from 2010 (Krogstad 2015). Florida in particular, now home to more than one million Puerto Ricans—rivaling New York—seems to be the preferred destination for those seeking to start their lives anew. Between 2000 and 2014, Florida’s Puerto Rican population saw a 110% increase (Krogstad 2015) while traditional destinations such as New York have been experiencing the out-migration of Puerto Ricans to other states—states such as Florida, currently the recipient of one-third of outmigrants from the island (Krogstad et al. 2017).

Our work has investigated the context of reception for Puerto Rican migrants in Central Florida (Aranda and Rivera 2016) and South Florida (Aranda 2009; Aranda, Hughes, and Sabogal 2014) and other issues surrounding their migration and settlement experiences. Whereas Puerto Ricans settling in South Florida, specifically Miami, encounter a city that is culturally friendly given the common use of Spanish and the lower likelihood of experiencing white racism; those who settle in Central Florida communities, although they experience the benefit of expanding social networks, still contend with racialization and navigating white/black race relations. Regardless of where they settle, as recent events (and Presidential Tweets) in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria have shown, Puerto Ricans continue to fight racial stereotypes that depict them as “lazy” and “dependent,” the legacy of their colonial status and current racialization projects.

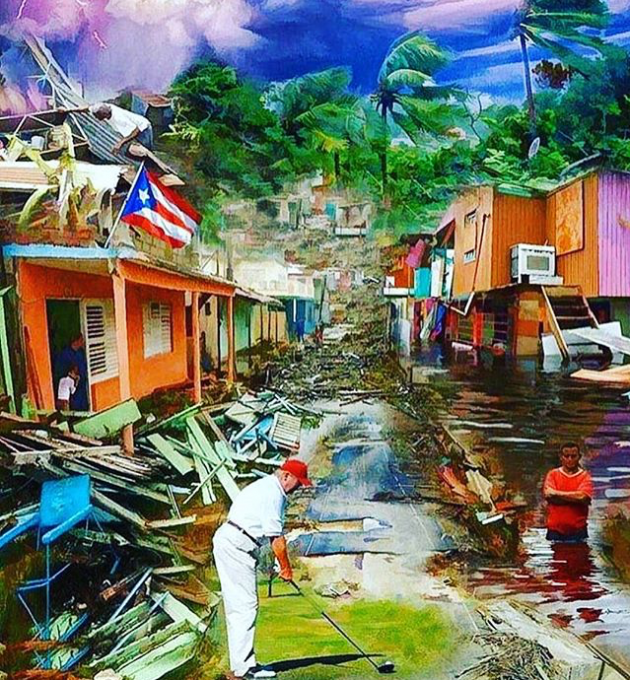

The preparation (or lack thereof) and slow response from the federal government has raised doubts about the nation’s commitment to the island; but this is nothing new. There were clearly competing examples of efficient disaster responses to Hurricane Harvey in the state of Texas and Hurricane Irma in the state of Florida that cannot be simply explained away by the geographical location (surrounded by “big water, ocean water”) of Puerto Rico. Reminding the world of Puerto Rico’s debt in the midst of a humanitarian catastrophe that has been described by some as “apocalyptic,” reveals the apathy (at best), and deliberate contempt (at worst) of certain leaders within the U.S. federal government toward the people of Puerto Rico.

The implicit and explicit message is that the people of Puerto Rico have not “earned” humanitarian relief, and that reconstruction is a question, and not a given—a response unheard of in the history of disaster relief toward U.S. citizens in this country. Family researchers point out that the most common form of child abuse is neglect; the United States, in paternalistic fashion, has long neglected the needs of the island. Perhaps this is because Puerto Rican islanders cannot vote in federal elections; perhaps the hurricane is just the tipping point of several other crises that were underway in Puerto Rico. Regardless of the reasons, the events surrounding hurricane response show that the U.S. government simply sees Puerto Rico and Puerto Ricans as peripheral and conditional citizens of this country and not worthy to be of central concern. Many in the community are wondering if this neglect has been purposeful, to pave the way for a mass migration so that billionaire investors can swoop into the island and make it into a playground for the U.S. 1 percent. Those Puerto Ricans left behind, who may not be able to afford to migrate, would comprise the serving class. This elevates the labor structure of the typical global city to the scale of an entire island.

U.S. neglect of the island may be nothing new, but it has certainly escalated in the wake of Hurricane Maria. While Puerto Ricans are U.S. citizens they have not enjoyed its full benefits. Compared to other Puerto Ricans in the continental U.S., Puerto Ricans on the island fare well below important socio-economic indicators including income, unemployment, poverty, education, health outcomes, among many others. Still, Puerto Ricans who migrate to the U.S. mainland are often marginalized into segregated and poverty stricken communities. As a result, Puerto Ricans have the worst health profiles of all Latinx groups in the U.S. (Rivera and Burgos 2010).It is too early to tell what will be the long term impacts of Hurricane Maria on the future of Puerto Rico, its people, and the Puerto Rican diaspora in the U.S. Amidst all the animosity created by the reprehensible tweets by President Trump, who unequivocally stated that Puerto Ricans wanted everything done for them, and the demeaning way in which the President distributed aid upon his visit to the island—by throwing paper towels for hurricane victims to catch—Puerto Ricans remain hopeful, though some doubtful, that the island will swiftly overcome the aftermath of the hurricane. The speed by which it may be able to do so will depend on the response of Puerto Rico’s local government, what resources the federal government will provide, the extent of mobilization of the Puerto Rican diaspora, and the level of interest in and action toward the island on behalf of the general American public.

Bold, yet reasonable actions need to take place, including (1) permanently waiving the Jones Act so that Puerto Ricans no longer pay double the cost for basic necessities compared to their mainland U.S. citizen counterparts; (2) passage of massive relief and reconstruction aid by Congress; (3) debt forgiveness in order to invest in reconstruction rather than line the pockets of Wall Street hedge fund managers; and, (4) allow island Puerto Ricans to vote for the President of the United States, so that instead of insulting the island’s people on Twitter or callously hurling supplies at them, the President may be more mindful of courting their vote, as he did when he addressed the effects of Hurricane Harvey in Texas and Hurricane Irma in Florida. We don’t need another hurricane to bring attention to the disparate treatment of Puerto Ricans. What we do need is action by Congress to, once and for all, stop the neglect of the Puerto Rican people and move in a direction of recognizing their dignity as fellow U.S. citizens who are worthy of investment.

Sources

Elizabeth Aranda. 2009. “Puerto Rican Migration and Settlement in South Florida: Ethnic Identities and Transnational Spaces.” pp. 111-130 in Ana Margarita Cervantes-Rodríguez, Ramón Grosfoguel, and Eric Mielants (eds), Caribbean Migration to Western Europe and the United States: Essays on Incorporation, Identity, and Citizenship. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Elizabeth Aranda, Sallie Hughes, and Elena Sabogal. 2014. Making a Life in Multi-ethnic Miami: Immigration and the Rise of a Global City. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publisher.

Elizabeth Aranda and Fernando Rivera. 2016. “Puerto Rican Families in Central Florida: Prejudice and Discrimination and their Implications for Successful Integration.” Women, Gender, and Families of Color, 4 (1): 57-85.

Jens Manuel Krogstad. 2015. “Puerto Ricans Leave in Record Numbers for Mainland U.S.” Pew Research Center.

Jens Manuel Krogstad. 2015. “In a Shift Away From New York, More Puerto Ricans Head to Florida.” Pew Research Center.

Jens Manuel Krogstad, Kelsey Jo Starr, and Alexsandra Sandstrom. 2017. “Key Findings about Puerto Rico.”

Sergio M. Marxuach. 2015. “Analysis of Puerto Rico’s Current Economic and Fiscal Situation.” Testimony for Hearing on Puerto Rico: Economy, Debt, and Options for Congress, U.S. Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources, October 22.

Fernando I. Rivera and G. Burgos. 2010. “The Health Status of Puerto Ricans in Florida,” CENTRO: Journal of the Center for Puerto Rican Studies, 22(1), 199-219.

Suffolk University, Political Research Center, National Poll with USA TODAY March 7, 2017, http://www.suffolk.edu/documents/SUPRC/3_7_2017_marginals.pdf.

Comments 2

Luis F. Gomez

October 18, 2017In the event that someone is searching for a (shiftless) Puerto Rican, I am prepared to offer myself. Let's see if I qualify: A) My mother & father spent less than five years going to elementary school. I have been married to the same woman for over 60 yrs., we have two children with professional degrees. I own three university degrees, one of which allowed me to earn a living representing poor people before racists judges & prosecutors. I have an honorable discharge from the U. S. Marines, where I made Sgt. in less than two yrs. I was able to retire debt free at age 82.

Jenny

December 22, 2017Great article! Thank you.