Resist, or What?

Social movements can shake the world. From the French Revolution, to the Bolsheviks, to the Mujahedin of Afghanistan, contentious groups have accelerated social change and toppled governments. But as social scientists, we know that these examples are atypical in their success and impact. When we step back to consider the whole range of contentious political behavior, from individual actions to social, regional, and topical activism we get a much bigger picture of ongoing contestation.

Consider the stereotypical “middle-class American homeowner.” In our imagination, these aren’t activists: they go to work, then retreat to their suburban home and its well-manicured lawn. They watch the news, they don’t make it. But stereotypes like these are easily undermined. Perhaps our suburbanite will run across a “NIMBY” (“Not In My Back Yard”) issue like the location of a factory or garbage dump, and they will spring into action, joining a neighborhood group, calling the city council, and demanding a halt to construction.

This thought experiment draws attention to the fact that activism can be local in character, triggered by the stresses and challenges of everyday life. But we can revisit it to ask what happens if the homeowner isn’t a stereotypical middle-class American. What will draw them into action? For example, what if this “middle-class homeowner” is queer or has a same-sex spouse? The stakes are higher. This homeowner may very well wish for the taken-for-granted stereotype from the first instance. Yet, when they sit on their couch and turn on the television, they see people calling for their ostracism from American society and institutions. They may pay higher taxes because their domestic relationship is not legally sanctioned. For them, the rupture between their aspiration and their quotidian experience propels them into action.

Tensions between the promised “American Dream” and what is delivered remain vital. After decades of successful activism and mobilization, Americans now enjoy freedoms and civil liberties that were simply unimaginable to their 19th century counterparts. We’ve seen voting rights expanded, same-sex marriage legalized. There are even movements questioning mass incarceration and the punitive narcotics legislation that enables it.

At the same time, America has witnessed a resurgence of anti-Black and anti-immigrant sentiment (see our Winter 2018 issue for commentary on Charlottesville and the rise of the “alt-right”). Undocumented people live fragile lives, from which parents and children can be ripped in an instant, sundered into a court system that punishes migration law infractions as if they were felonies. Activism is both a necessity and a reality of our modern lives.

Thus, we can ask: Do these movements matter? What should they do? We’ve gathered some of the leading social movement scholars in the discipline of sociology, and each has tackled these questions uniquely. David Pettinicchio focuses on the disability rights movement and how social change is always incomplete and subject to implementation and enforcement. Pamela Oliver, one of sociology’s leading scholars of activism, discusses how movements succeed only when they understand that politics is a constantly evolving struggle. Jennifer Earl, a scholar of movements and youth, offers insights into constructively engaging and taking leads from young people who aspire to activism. Matthew W. Hughey discusses the instability of racial attitudes and how they might be best viewed as a sort of cultural toolkit driving public engagement. And, finally, Melissa Brown brings us to the cutting edge of activism, using social media data to consider the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement and what may come next. Use these insights, read through your own sociological imagination, then get out there and change the world. fabio rojas

— Fabio Rojas

- Retrenchment and (Re)mobilization, by David Pettinicchio

- Strategic Thinking, by Pamela Oliver

- Youth Protest’s New Tools and Old Concerns, by Jennifer Earl

- Schrödinger’s Whiteness, by Matthew W. Hughey

- Studying Black Feminist Activism in the Era of Social Media, by Melissa Brown

Retrenchment and (Re)mobilization

by David Pettinicchio

The politics of retrenchment is a powerful, threatening force mobilizing citizens by reminding them that nothing—not even their civil rights—should be taken for granted. Ed Roberts, founder of the independent living movement, said at a protest nearly 40 years ago, that “politics is pressure.” For people with disabilities and other increasingly marginalized groups, that statement still rings true today. Indeed, the disability community is no stranger to policy innovation followed by back-stepping and broken promises.

Disability rights legislation has been regarded among the most bipartisan projects the U.S. federal government has ever embarked upon. A half-century ago, political entrepreneurs carved a path for disability rights in the government culminating in Section 504 of the 1973 Rehabilitation Act—the product of institutional activism by elites in both parties. However, retrenchment began almost immediately, as administrations and the courts worked to undermine Congress’s intent to enshrine equal rights and eliminate discrimination. Empowered by new rights legislation and facing political backlash, the movement in the government became a movement in the streets.

Responding to these threats throughout the 1980s, nascent groups like the Disability Rights Education and Defense Fund (DREDF) and ADAPT, joined existing political advocacy organizations like Disabled in Action to coordinate demonstrations and sit-ins. They targeted the courts, federal government agencies, state and local governments, as well as public and private corporations. Movement leaders, professional advocacy organizations, and both Republican and Democratic members of Congress worked to restore Section 504, which had been whittled away by the courts and the Reagan administration. The political dynamics surrounding disability policy entrenchment in the Reagan era point to the key role of activists both inside and outside the government in shaping one of the most important pieces of civil rights legislation: the 1990 Americans with Disabilities Act.

Heralded as the “emancipation proclamation” for people with disabilities, the ADA was nonetheless beset by incremental efforts to undermine compliance and enforcement. These efforts gained less public attention than the retrenchment efforts of the ‘70s, but following a decade of devastatingly restrictive court rulings on the ADA, Congress again revisited the law in the late 2000s. Some 40 years after Congress first introduced disability rights onto the policy agenda, it passed the disingenuously named ADA Restoration Act.

To be sure, the post-ADA era saw important episodes of mobilization and confrontation. For example, ADAPT intensified its lobbying efforts targeting federal policy regarding in-home care funding while protesting the nursing home industry. Yet, overall, the period was one of consolidation among disability organizations, decline in sustained protest activity by the disability rights movement (especially targeting the federal government) and, a diminished role of the federal government as a forceful actor in the disability rights struggle. Many had grown concerned that the ADA wasn’t doing its job given declining employment rates and stagnant earnings among people with disabilities. Activists, policymakers, and scholars all found reason to label the ADA a “failed” policy.

The disability community today once again finds itself wondering about the future of their civil rights. In June 2017, ADAPT organized a protest outside Majority Leader Mitch McConnell’s office. They were fighting against the Republican health care bill’s threats to independent living via Medicaid cuts that would force many people with disabilities out of in-home care and into isolating institutions. In contrast to their Republican predecessors, including former Republican Speaker Newt Gingrich who worked to address the bias in Medicare funding toward nursing home care, today’s Republicans seem to have disregarded those efforts as well as the spirit of the pivotal 1999 Olmstead Supreme Court case that reaffirmed disabled people’s right to live in communities instead of institutions. As one activist proclaimed, “Our lives and liberty shouldn’t be stolen to give a tax break to the wealthy. That’s truly un-American.” Police dropped an activist on the ground as they arrested and forcibly removed 43 protesters from the Majority Leader’s office.

The 2017 ADA Education and Reform Act also proposes relaxing requirements for businesses to provide reasonable accommodations for people with disabilities. “No other civil rights group is forced to wait 180 days to enforce their civil rights,” read a statement from the American Association of People with Disabilities (AAPD) and DREDF asserted that the Act would “take the heart out of the ADA.” The Trump administration has further signaled federal government retreat from disability rights by putting Department of Justice enforcement of the ADA’s titles pertaining to the accessibility of websites, medical equipment, and public accommodations on an “Inactive Actions” list. And, proposed cuts to legal services and Protection and Advocacy Services would make it increasingly difficult for victims of employment discrimination to access and mobilize their rights.

Federal courts have also demonstrated their unwillingness to take on potentially important disability rights cases that require reviewing the effectiveness of existing legislation. In October 2017, the Supreme Court decided against hearing a case about inaccessible vending machines. The Trump administration, along with Coca-Cola, had apparently urged the justices not to hear the case. The Court also declined to hear an appeal regarding the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act’s (IDEA) “stay put” rule, which allows a student to remain in a regular classroom while disputes between parents and the school about placement into a self-contained classroom are resolved.

No one really knew in practical terms what Trump and his administration had in store for disability rights policy when they arrived in Washington. We know now: Their efforts are insidious and will mean the rollback of a half-century’s worth of progress. And there has been little public outcry outside of the disability activist community. Now, more than ever, the disability rights struggle is relying on the mobilization of everyday Americans in nonviolent direct action to combat new political threats. Policy victories are never total. They do not always settle underlying conflicts about even fundamental citizenship rights.

Strategic Thinking

by Pamela Oliver

A social movement field is like a game with dozens of teams playing simultaneously—and nobody’s in charge. The rules shift unpredictably, even as the teams try to strategize and anticipate others’ moves.

The game we’re playing in the U.S. today includes two large alliances centered around each of the major political parties. Each includes both strong partisans, whose main allegiance is to the party, and issue-specific social movements. There are ideological disagreements, bitter in-fighting, and jockeying for position within each alliance. The Republican alliance has gained control of the federal government and most state governments, but the Democratic alliance was recently in power and still has substantial power in some regions. Most White people (about 55-60%) support the Republican alliance, while a very large majority of racial/ethnic minority people support the Democrats. The racial divide is largely due to the Republicans’ Southern Strategy of making White identity appeals. Overt White nationalists are part of the Republican alliance, while minority movements are part of the Democratic alliance. Democrats are divided along a Clinton-Sanders division, and the Democratic alliance includes left-leaning social movements that waver in their support for centrist Democrats. Different actions and policies threaten different constituencies.

What role do anti-Trump protests play in this field of alliances? It depends on your goal. If your goal is to express your outrage, protest is the way to do it. But for other goals, protest may or may not be helpful.

Some groups are focusing on electing Democrats in 2018 and 2020. Their main tasks are finding candidates, identifying and registering voters, and getting out the vote, and there are bitter debates about how to do this. Just as the Republicans successfully mobilized opposition around health care in 2010 by protesting at local meetings and joining Tea Party protests, Democrats may be able to energize Democratic voters via protests focused on salient issues and, importantly, tied to electoral organizing efforts. But protests against politicians contribute to polarization and mobilization on both sides. The 2011 “Wisconsin Uprising” against the policies of Governor Scott Walker strengthened both support and opposition to him, with a net effect that he survived a recall election (despite a million signatures on recall petitions) and won reelection in 2014. Broad anti-Trump protests might have a similar effect, strengthening his appeal among those who were, initially, only weakly attracted to him. On the other hand, anti-war protests in the 2000s helped build opposition to the Republican president, and protests may help motivate Democratic voters looking to the 2018 and 2020 elections. The massive protests around gun laws in March 2018 have included strong messages about registering and voting in the fall midterm elections.There are different calculations being made by the broad range of organizations and activists that make up the Black movement as a whole. After two years of mobilization around the phrase “Black Lives Matter” and the Ferguson protests, there was an intense protest phase in the summer of 2016. These mobilizations rekindled Black Power politics, put younger Black activists into dialog and confrontation with older Black activists, drew in White supporters, and gained institutional concessions. The movement sought to shift to a proactive rather than reactive stance and use its momentum to draw support for issues beyond policing. The Movement for Black Lives rolled out an ambitious and proactive social change agenda in August. But even as it won victories, the Black Lives Matter mobilization increased the salience of racial identities. Counter-movements had mobilized, including “All Lives Matter” and “Blue Lives Matter” and there was even a revival of the 1960s John Birch Society’s “Support Your Local Police.” BLM was accused of fomenting attacks on police. The Trump campaign drew upon and fed these counter-movements. Already-intense police repression of Black protest increased post-election, with the FBI even calling “Black Identity” organizations terrorists, in an eerie echo of its stance toward the Civil Rights Movement. The Black Movement has not gone away, but has shifted strategy. Black activists were already planning for a possible Trump victory as early as September 2016 and have settled in to fight in this less favorable political climate. There will probably be fewer proactive protests, although there will still be reactive protests in response to police violence and local campaigns will continue. White ally groups have declined, shifting to other issues as the Trump administration takes aim on group after group.

If you are a Muslim, an immigrant, a DREAMER, a gay or trans person, or someone who wants to support them, the goal is to find ways to protect vulnerable minorities who have few legal protections. Popular demonstrative protests by members of the White cisgender heterosexual majority can demonstrate that stigmatized minorities are not alone, and certain kinds of mobilizations, such as the airport protests or Sanctuary movements or legal aid mobilizations, seek to provide direct assistance in protecting people. Mass protests by stigmatized minorities seem less likely, as all these groups are extremely vulnerable to repression and violent attacks and are already suffering losses.

For all of these groups and others, activists must always consider their strategic position, goals, power, resources, and relation to other groups in the field. They must anticipate the possible actions their fellow players will take, in the short and long term. Relatively spontaneous protests that arise in response to suddenly imposed grievances either work or do not in removing the immediate problem. For longer-term change, protest is generally not an end in itself, but a tactic used in conjunction with other tactics. Protests can draw media attention, can attract and motivate supporters, and can signal popular opinion, but protests can also alienate potential allies and draw repression. Strategic activists who want to win are also nimble: while continually adjusting their tactics in light of what all the other actors in the game have done, they shore up their team, reinforce alliances, and keep their goals in mind. And should a social movement come out on top, its supporters and allies must keep up the fight. This game never really ends.

Youth Protest’s New Tools and Old Concerns

by Jennifer Earl

From White supremacy and domestic terrorism to climate change, potential nuclear conflicts, rising income inequality, and beyond, young people will inherit the world the Trump administration leaves them. Of course, this is always true: even the most well managed, forward-looking administrations have been vexed by these problems. But today, many of these issues are even more global and some may involve tipping points after which their consequences become far less manageable. These troubles are also being passed along with adults’ skepticism about the role and capacities of young people as political actors.

Fortunately, research on youth engagement and activism suggests young people coming of political age in this crucial moment are both better positioned to intervene politically than they are often given credit and have access to powerful new digital political tools. To some, the question of how to match these tools to the problems at hand is a technical issue about platforms and technology, but I believe the most important considerations aren’t technical. They aren’t even specific to the “newness” or digital nature of newer tools, but hinge on classic issues facing activism. My own work and that of my collaborators on digital activism, as well as my participation in the MacArthur Foundation’s Youth and Participatory Politics Research Network, has highlighted the interplay between old problems and new political tools.

For those adults and movements that hope to inspire and engage young people, there are four particularly important take-aways from research on youth activism. First, young people have their own distinct problems, needs, and solutions; they are not miniaturized adults. As research by Thomas V. Maher, Thomas Elliott and myself shows, being young is an identity and can even be a collective identity that needs to be in the mix with other intersectional identities including race, ethnicity, gender, class, and sexuality. But, movements that aren’t explicitly youth-led often forget this, and they bear partial blame for any suboptimal youth engagement. For instance, on cause-oriented digital media, adults often produce content about or for young people, but rarely do they recruit young people to produce content for each other or for adults. Nor do they specifically reach out to young people as participants. So, just as feminism has been criticized for actually being White feminism, research suggests that movements are really older people’s movements. If we care about the future of those youth coming of political age and about the movements that affect them, we must make room for youth activism.Second, many adults and movements assume young people aren’t politically interested or engaged. Adults often operate as if their job is to rectify some political deficit disorder that afflicts youth. But, young people are actively assimilating their experiences and what they read, see, discuss, and learn into their emergent political selves. Movements will likely do much better engaging young people if they extend encouragement and interest over messages like those Malcolm Gladwell expressed in his 2010 New Yorker piece, “Small Change.” Rarely has saying, “you’re doing it wrong, let us show you the right way,” drawn hordes into sustained activism.

Third, there is a tendency to assume that because young people are “digital natives,” they don’t need help figuring out what to trust online and how to use digital and social media to learn about, take action on, and influence others around issues they care about. Schools and clubs should help youth develop curricula about assessing the quality of information and sources they find online and how others have influenced the political system in the past and today. Educating for Democracy in the Digital Age, a research-based project from TeachingChannel.org, provides one good example.

Finally, movements need to court youth by connecting with their interests. There are lots of “big-P” politics in fashion (for example, outsourcing and labor), in entertainment media (sexual harassment and minority representation), and in sports (Take a Knee and long-term mental health). If movements assume that the only young people they should be concerned with are those who already self-identify as politically engaged, they are overlooking a huge pool of potential activists. As outlined by Ziad Munson in The Making of Pro-Life Activists, some people get involved in a movement and then become believers. Many social movements and scholars are also missing the social justice message and possibilities that groups like the Harry Potter Alliance have capitalized on to drive activism, turning fans into changemakers.

It’s not just that adults and movements need to reconsider some of their assumptions about how to interact with youth, but also that we need to reconsider the idea that when it comes to using digital media, everything is new. If one wants to understand how to use digital and social media for social change (whether by young people or seasoned movement participants), research suggests it comes down to some of the same issues that activists have addressed in the past. Three of these stand out.

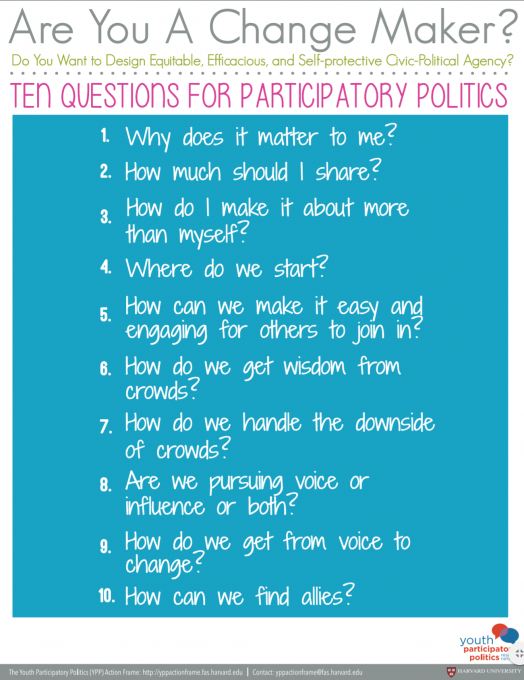

First, organizers should develop a theory of influence to drive their strategic, tactical, and technical decision-making. Is the goal to publicize a bad act, promote a good policy, or raise awareness? Shame a target into taking some corrective action? Encourage an ally to do more? Gain traditional media attention? Get specific kinds of online thought leaders to talk about your issue? If activists and movements begin by thinking about who and how they hope to create influence, figuring out how to use digital or social media to facilitate that influence follows more easily (see the Youth Participatory Politics Research Network’s “Ten Questions for Changemakers,” below).

Second, movements need to remember that getting people to do anything is most likely better than having them do nothing. Many scholars, public commentators, and activists have an idealized vision of high-stakes activism that overlooks the good done by smaller actions that people can take immediately and forgets that most people don’t act at all to make change. Movements that create a variety of entry points and forms of engagement—valuing both low- and high-cost forms of engagement—will engage more people and pull many people off the sidelines through easier asks.

Third, activists and movements need to realize that repression—both public and private—happens online, too. The Internet can be mean. Adults and young people who engage online need to be prepared for pushback and to consider technical issues that may help them manage that pushback (e.g., Do you want to use a site that has a real-name policy? Should you segment your activism across different platforms?).

Young people in every era have a lot to gain and lose in politics; after all, decisions made today will affect them for far longer than they will affect those already-seasoned activists. Rather than simply trying to “stand with youth” by opposing policies that might have long and dangerous legacies, we must also consider how to stand with youth by recognizing their concerns and needs as potentially distinct from adults, by thoughtfully using digital and social media, and by working side by side with youth.

Schrödinger’s Whiteness

by Matthew W. Hughey

The lines are drawn: Republicans versus Democrats. Rural working class versus urban elites. Traditionalists versus progressives. #MAGA versus #ImStillWithHer. These are the conventional dichotomous short-hands circulating in the wake of the 2016 election.

Distinguishing and collapsing worldviews amidst the heterogeneity of Whiteness, an array of scholars, pundits, and laypersons chart the proverbial “good” and “bad” White people—drawn from a constellation of economic, political, and social attitudes. Then they set out to determine, based on these correlations, what variables best predict who will take up either the challenge to “RESIST!” or support the chief resident of 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. Such perspectives seem to provide some evidence for the oft-evoked social scientific adage: “demography is destiny.”

In my years of ethnographic analysis among all-White organizations in the mid-Atlantic, deep South, and New England (a cacophony of Whites that cuts across gender, class, political, and economic divisions), I certainly find conventional attitudes that resemble our modern political culture war. But I also find evidence of paradoxes and changing attitudes that bring to mind physicist Erwin Schrödinger’s famous thought experiment.In 1935, Schrödinger wanted to know when a quantum system (like an atom or photon) stopped existing in “superposition” (or contradictory states) and began to behave in a more conventional or classical manner. Schrödinger imagined a cat and poison unobserved inside a box. At some point, he surmised, the cat must be assumed to be simultaneously alive and dead—until an observer can empirically confirm the cat as one state or the other, one could only believe it was both. Schrödinger’s insights continue to shape debates within quantum physics, and I think that what we sociologically know and predict is similarly entangled with when, from where, and how we observe.

Hence, I neither assume White racial “attitudes” established and stable, nor do I accept that White folks produce spontaneous narratives whole-cloth. While Whites have shown dramatic increase in support for the principles of racial equality—especially in jobs, schools, and public accommodations—these supposedly predictable trends are often thrown out the window when taking such a stance means “losing face” in front other White people. Moreover, the stories that White people use to defend labor discrimination, oppose affirmative action, or resist public integration are irreducible to personal and atomized choices. Thus, I examine White inconsistencies as “superposition strategies” in the ongoing accomplishment of White racial identity. Supposedly paradoxical statements help create a sense of self-efficacy and coherent White racial identity within changing social situations, whether it be White women’s participation in the 2017 Women’s March or their actions in the voting booth months prior.

For example, many Whites spoke of Latinos as “lazy” at one moment and “industrious” the next, marshalling both narratives to defend or rationalize the privileged place of Whiteness in relation to immigration policy, employment law, and cultural belonging. Black/White inequality was sometimes framed as a matter of African Americans needing to engage in Horatio Alger-style individual bootstrapping initiatives, and, at other points, such discussions evaporated into claims that Black folks are too dysfunctional or pathological to be independent actors. And quite frequently, Whites described various Asian ethnic groups as isolated, closed, and secretive, while praising them the next moment for their “model minority” endeavors to Anglo-assimilate.

Depending on the context and audience, these varying perspectives were employed to paint oneself as the “right” (e.g., intelligent, moral, hardworking, etc.) type of White person. Such narratives helped construct inter- and intra-racial distinctions whereby the speaker was unlike both people of color and/or other somehow deficient White people. Similarly, my students Devon R. Goss (examining White HBCU students and White ex-pats in Mexico) and Michael L. Rosino (studying White grassroots progressive activists in the Northeast) have found idealized White identities that, while intimately bound with essentialist and reactionary assumptions, alter as context befits them. White identity is built through both shifting opposition to, and in alliance with, varied distinctions—a marker of an ideal White identity worthy of pursuit.

A mixture of contradictory states, Whiteness is a shifting category. What does it mean for examining Whiteness in the post-Obama age of Trump?

Studying “race” is the attempt to make sense of nonsense. Race has no biological validity and has been arbitrarily and inconsistently defined over time and space. Yet, it exists as a robust social fact. Making scholarly meaning out of intricate, nuanced, and detailed contradictions in everyday social interactions, both across the color-line and within racial groups, remains the task of critical sociological analysis. We must embrace complexity and theoretical dilemmas as scholarly hot spots, rather than as outliers we can dismiss because they do not fit Janus-faced moralizing or predictive models.

I suggest three practical steps for the sociologically inclined as we continue to encounter the dominant racial groups’ Schrödinger-like resistance/collusion with the White supremacy, xenophobia, and Nativism of the Trump administration and whatever comes next. First is the matter of time. Slow down. When moving quickly, we too easily miss the everyday inconsistencies of people’s mundane activities. What changes and morphs instead appears static. Such relativity, or what W. E. B. Du Bois called “car-window sociology,” does not seek to unravel the “snarl of centuries.” Rather, taking quick glances at issues, we tend to calcify singular moments of time, which we then aggregate and assemble as a skeleton on which we hang the meat of our interpretations.

Distance is my second concern. Get close to the object of your research. Far up in our ivory towers it is difficult to gauge the causal mechanisms and operations of the particular opinions we believe Whites hold so steadfast. Don’t get me wrong—from a bird’s-eye perch, sociologists make many excellent generalizations. But there is a trade-off; we do not accrue explanations for how and why phenomena vary, relate, and operate in the first place.

Third is the difficulty of scale. In fetishizing “big data” we yield to an obsession with reliability and predictability over understanding. We fall prey to what C. Wright Mills derided as “abstracted empiricism” or we slip into a tendency to address only those social problems that fit our conventional methods and underlying analytic suppositions.

All these cautions apply equally to those who wish to interpret the world and those who wish to change it. Activism does not always assume the shape of Social Movements®. The everyday actions White people take in pursuit of an idealized racial identity are engagements that both augment and abate inequality; the cult of Whiteness is itself a social movement. To understand its “recruitment” and “mobilization” tactics, look beyond situated “political” activities and “moral” stances toward the consequences of everyday White interactions. The noted sociologist Erving Goffman said it well: “The trick, of course, is to differently conceptualize these effects, great or small, so that what they share can be extracted and analyzed, and so that the forms of social life they derive from can be pieced out and catalogued sociologically, allowing what is intrinsic to interactional life to be exposed thereby. In this way one can move from the merely situated to the situational…”

Until we approach White identity formation as a situational process of legitimating and rationalizing White interests, we will continue to dismiss White nationalists as outliers suffering from mental disorders and overstate the power of positive trends in White attitudes to stand as short-hand for a healthy society. We’ll miss the everyday paradoxes and inchoate strategies endemic to the social movement of Whiteness. When we observe the process of White identity formation, we get a look inside a box rarely opened.

Studying Black Feminist Activism in the Era of Social Media

by Melissa Brown

I came into graduate school at the University of Maryland (UMD) expecting to pursue research on Black women in reality television. I had grown up fascinated by Real Housewives of Atlanta and Love and Hip Hop, by television networks framed the women on these shows and how the audience interpreted those images. At the start of my second year, though, the death of Michael Brown shifted my research interest to social media activism.

Recently, Ethnic and Racial Studies published two of the studies I worked on. They grew out of an interest in #BlackLivesMatter, the call-to-action launched against anti-Black violence in 2012. Ed Summers, a programmer at the Maryland Institute for Technology in the Humanities (MITH), had the savvy to collect over 31 million tweets containing the word “Ferguson,” the Missouri city thrust onto the international stage after police officer Darren Wilson killed teenager Michael Brown. I learned about Ed’s Ferguson Twitter dataset at a 2014 townhall on Brown’s death held at UMD.It had only been three years since I joined Twitter and, as a Black undergraduate at the University of Georgia (UGA), embraced Twitter activism around the then-impending execution of Troy Davis. Then, I’d seen my fellow students take their social media activism into the real world with a silent, on-campus protest of Davis’s execution. Like UMD, UGA had an institutional response to the death, too, but the scale was different—smaller. In the time between being an undergraduate doing social media activism and becoming a graduate student researching social media activism, so much would change about our collective responses to state-sponsored killings.

Now I reached out to Ed about the Ferguson dataset. MITH invited scholars to attend sessions on it, teaching scholars about digital tools they could use for, Twitter data collection, archiving and analysis. They also provided personal consultations that helped me understand the methodology underpinning social media data analysis. Thereafter, my advisor, Rashawn Ray, and I partnered with Ed and the director of MITH, Neil Freistat, to conduct a content analysis of the Ferguson dataset. Our analysis of the tweets provided insights about how social groups responded to Ferguson in divergent ways, yet shared a specific common stance: silence with regard to women victims of police violence. By this point, a few studies had noted the importance of social media in modern social movements, and it was this same silence around Black women victims of police violence that inspired Black feminist scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw to start the #SayHerName hashtag.

As a Black feminist scholar, I often begin with Black women as my unit of analysis. I want to know what general insights we learn when we center Black women. And #SayHerName offered an opportunity to examine social media activism as it pertained to Black women and Black feminism. A content analysis of the 400,000 tweets Ed had collected showed that Twitter users tweeted #SayHerName to memoralize over 100 Black women victims of police violence, intimate partner violence, and transmisogynistic violence. (Though #SayHerName tweets centered Black women, a few non-Black women of color were highlighted. This approach to social justice recognizes that all oppression occurs within what Patricia Hill Collins terms a matrix of domination.) Few of these victims ever received national or international media attention. But Black women and their allies used Twitter and the hashtag to link to blog posts, local news sites, and independent digital publications. Most of the pieces they linked to had been authored by other Black women.

Despite the innovation that social media offers activists, it clearly has drawbacks. The format of most social networking sites makes it relatively easy to spread news and maintain community with like-minded thinkers, yet it also reinforces echo chambers and increases resistance to outside information. And even successful sites, like Twitter, struggle to secure their financial futures. Limitations the platforms impose can change what activists are able to do with those platforms—Twitter, after all, reserves the right to arbitrarily remove a hashtag. We must ask: What happens if this channel of communication gets lost? How can supporters of social media movements gather to speak to how state violence affects them when these technologies fail?

My research helped me grasp how narratives about the digital divide obscure Black feminist organizing on Twitter. Before I studied it myself, I, too, equated “hashtag activism” with “slacktivism,” lowering the costs of participation in a social movement and dampening the real-world investment in it. But my findings told me that people armed with a cellphone and a social media account used them to document offline protests and share information with the masses. We must not disregard the capacity for organizing and amplifying that social media provides. Nor, as we use social media to protest this current political regime, can we allow ourselves to obscure the voices of those most marginalized in favor of the “same old story” of injustice. Social media is a tool that transcends time and space, but it relies on real world activity to sustain a hashtag as a movement.

Revealing structural oppression also occurs well beyond a single digital platform. Crenshaw recently gave a TEDWomen talk that highlighted #SayHerName, and organizers across the U.S. have put together panels, protests, and teach-ins inspired by #SayHerName to generate conversation about violence against Black women. Black feminism didn’t begin in the age of Twitter; it began when Black women first sought to be freed from their chains. Twitter or no Twitter, Black women have always found powerful ways to organize and demand change.