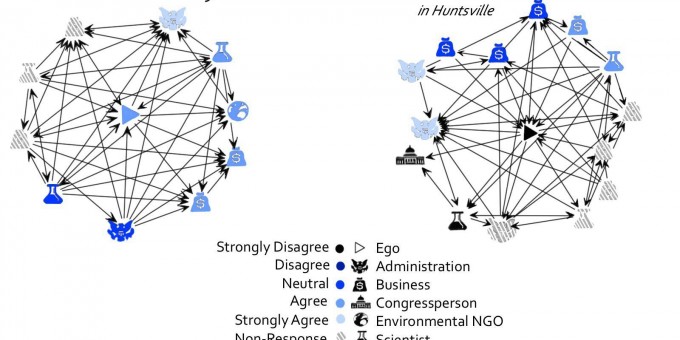

Ego networks of two respondents, shaded based on agreement with the statement: "There should be an international binding commitment on all nations to reduce greenhouse gas emissions." © Fisher, Waggle, Jasny 2015.

Science and Politics

The quest of science to understand how the world works is inextricably tied to and bound by political machinations and social biases. This, of course, is a very old story. We only need think of poor Galileo, convicted of heresy by the Inquisition in 1633. It would be nearly 200 years before the Catholic Church conceded that, indeed, the earth does rotate around the sun.

Many of the articles in this issue deal with the social and political entanglements of science. In this issue’s Viewpoints, the authors examine how scientific evidence is sidelined in public policies. The federal government deems marijuana a lethally dangerous drug, on par with heroin, despite its medical uses and low-risk recreational appeal. While some states have made moves to decriminalize or legalize medical or recreational marijuana, its sale and use remains illegal at the federal level, and the federal government could at any time change its policy of benign neglect toward these states.

For science to help shape policy in constructive ways, it has to be heard. In the case of climate change, echo chambers—closed information flows—allow politicians to hear just the science that serves their interests (and those of their backers), as Dana Fisher, Joseph Waggle, and Lorien Jasny show in “Not a Snowball’s Chance for Science.” We sociologists know all too well that there’s always a scientific expert available to provide validation for politically motivated policy positions.When it comes to hydraulic fracking the science is no less contentious, but the role that science plays depends on the efficacy of the social movement actors mobilized to expose and oppose the extraction method’s harms. In Trends, Brian Obach explains how that mobilization produced a major victory in New York State.

Contemporary science controversies bubble up over everything from the tiniest DNA fragments to the biggest weather patterns, and everyone is affected, from the least powerful people (in low-lying coastal areas of poor countries) to those in the seats of global power (like Oklahoma’s Republican Senator “Snowball” Jim Inhofe and multinational oil barons). There’s a lot at stake politically in the dissemination and teaching of science, and sometimes it feels like it’s all on the shoulders of a middle school science teacher—in this case one who decides to conceal his sexual orientation from his students out of a sense of dedication to his professional role, as Catherine Connell describes in “Pride and Prejudice and Professionalism.”

Politics is also deeply embedded in the social sciences, whose history is written into their language, customs, and methods. When that history is unseen—obscured, distorted, denied—then the science may be impaired in the service of inequality. This is the story of W.E.B. Du Bois and the origins of modern American sociology, as told in Aldon Morris’s new book, The Scholar Denied, and Alford Young, Jr.’s review.

In this issue, we also bring you a whole lot of other fascinating reads, including a photo essay on people sleeping on sidewalks, under bridges, and atop motorcycles in Bombay (sorry, Mumbai), and a Culture essay on Depression-era photographer Dorothea Lange, one of the original visual sociologists. Tuck in and see for yourself.