Why Sociology Needs Science Fiction

“You can’t tell a story like [the financial crisis] with realism. You need fantasy to explain it.”

–Max Gladstone, author of The Craft Cycle

We live in a science fictional society. Cyberspace (a term coined by sci-fi author William Gibson) has dissolved into a cyborg present, an “augmented reality” as sociologist Nathan Jurgenson puts in, where online and offline are intertwined, albeit with the seams still showing. The problems we collectively face combine the abstraction of a cutting-edge computational simulation and the immediacy of an impending hurricane. One of the latest political scandals involves a company called Palantir, named for a corrupted crystal ball in J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, receiving secret contracts with city governments to test its big data-fueled predictive policing technology (for more on Palantir, check out Sarah Brayne’s recent article, “Big Data Surveillance”).

At the same time, the central concerns of sociology remain as relevant as ever. Powered in part by new social media tools, movements including #BLM and #MeToo have reinvigorated the public discussion around racial and gender inequality; using the same tools, White supremacists and misogynists target their hate online and off. By many measures, economic inequality in the United States is at an all-time high, and the fear of “robots taking our jobs” is just the newest iteration of insecurities around technological unemployment and the welfare state that social scientists have debated for more than a century. In 2018, we may speak in a science-fictional jargon, but our concerns are classic sociology.

What can we learn from the intersection of science fiction and sociology? Let me offer hints of five interconnected answers.

First, science fiction can help us understand reality in much the same way as a well-constructed Weberian ideal type. For years, social theory instructors have turned to Terry Gilliam’s Brazil to showcase the excesses of bureaucracy, or to Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times to help students see the alienation of labor in an unrealistically, but theoretically generative, pure form. More recently, Black Mirror’s “Nosedive” episode perfectly encapsulated Marion Fourcade and Kieran Healy’s vision of a society increasing stratified by credit scores and app rankings. Beyond their explicit pedagogical value, shows like Black Mirror provide a common language for fan communities to make sense of present events. We talk about the news, pointing to one another and saying, “That sounds just like the episode where…!”

Second, science fiction offers a reservoir of “extreme” counterfactuals. I like to think of counterfactuals in three rough types. The easiest sort of counterfactuals are those that were really tried and tested in the historical case—roads that were considered and almost traveled, false starts that gained some momentum but were edged out by an alternative. These counterfactuals are often quite similar to how history unfolded, with, perhaps, a few consequential tweaks. Another sort are counterfactuals that were imagined and available to historical actors, but which were never seriously pursued. Finally, there are extreme counterfactuals, worlds so different that it takes a great leap to even imagine them. Sci-fi, especially in its alternate history mode, specializes in this sort. Amazon’s show The Man in the High Castle (based on the Philip K. Dick novel of the name) is exemplary, imagining a present-day U.S. situated in a world in which the Nazis won World War II.

Third, and related, science fiction offers a complement to history and anthropology as a source for alternative visions of society. When sociologists grapple with the big transformations of modernity, we often struggle to characterize how else things could have been. Ursula K. LeGuin’s vision of a communist society in The Dispossessed is an impressive, fully envisioned society, not just a utopic promissory note. Similarly, Black Panther asks us to imagine a world in which an African technological superpower evaded colonialism and emerged as a player in 21st century global politics.

Fourth, in offering a wellspring of alternative visions of society, science fiction can offer inspiration for imagining a more just society. From LeGuin’s communist and feminist sci-fi ethnographies to W.E.B. Du Bois’ imaginings in “The Comet” of an apocalypse sufficient to bring about racial equality, sci-fi has long invested itself in the question of what a just society could look like. In its more pessimistic and apocalyptic modes, sci-fi also offers visions of futures to avoid, from the surveillance states of Black Mirror, to the patriarchal world of Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale and the climate change dystopias of Paolo Bacigalupi.

Finally, sci-fi is itself a social field in the world, characterized by its own norms, cultures, logics, and inequalities. While it’s easy to identify a progressive orientation to many of sci-fi’s visions of the future, there is also a long tradition of sexist and racist sci-fi writing. The tension between these visions played out recently in the sci-fi fan community through a series of controversies around sexism and racism. This most visible confrontation focused on the Hugo Awards, one of sci-fi’s most prestigious honors selected by a vote of fans themselves. A faction of conservative fans, angered by their perception that the awards had been dominated by progressive “Social Justice Warriors”, mobilized an unsuccessful campaign to try to steer the awards toward “harder” sci-fi, often with military themes, written mostly by White men. More broadly, sci-fi fans and authors of all political orientations struggle with the politics of genre and classification and their ambivalent quest for recognition and distinction. Work that is “too sci-fi” gets cast as niche and unserious, while some works with obvious sci-fi themes are placed in the more prestigious “literary fiction” category. American sociologists interested in the politics of culture and in the politics of resentment could look to sci-fi as a useful microcosm of debates playing out across the country.

In this issue, our contributors take up these concerns in four short essays. Philip Schwadel applies theories of communicative functions to look at sci-fi’s potential to shape our social understandings. Ijlal Naqvi returns to Isaac Asimov’s Foundation to argue that dreams of perfect social prediction will remain elusive and perhaps undesirable. Erica Deadman showcases how well LeGuin’s Left Hand of Darkness illustrates ideas from the sociology of gender. And Rick Searle looks at “micro-democracy” and the politics of Information in the recent Centenal Cycle books by sci-fi author (and trained sociologist!) Malka Older to find possibilities for alternative political futures.

Sociologists will need new metaphors, new ideal types, new counterfactuals, and new guiding lights as we navigate the 21st century. We face new problems, like anthropogenic climate change, and old, enduring ones, like the Color Line. Science fiction can help. And perhaps, along the way, science fiction can learn a thing or two from sociology.

- Grokking Modernity, by Philip Schwadel

- Resistance and the Art of Words, by Rick Searle

- A Planet Without Gender, by Erica Deadman

- Beware of Geeks With Good Intentions, by Ijlal Naqvi

Grokking Modernity

by Philip Schwadel

Without science fiction, I might not have become a sociologist. The novels I read as an adolescent were replete with sociological themes that resonated with my growing understanding of the social world. Isaac Asimov’s Foundation series introduced me to the idea that aggregate behavior could be predicted using quantitative techniques, which (on a less grand scale) is what I now do for a living. Sci-fi plays important sociological functions, most notably by challenging people’s understanding of the social world.

Novelist and trained sociologist Brian Stableford (who wrote The Sociology of Science Fiction in 1987) argues that, like other media, sci-fi reflects the goals of the author(s) and enumerates three types of communicative functions it performs. First, it is restorative, serving as a form of escapism. Although Stableford suggests that this type of communication is unlikely to have a lasting impact on readers, from a Simmelian perspective, fantastical pastimes may be essential in a modern world overflowing with sensory stimuli. Second, the maintenance function supports and legitimates readers’ existing attitudes. From a Durkheimian perspective, maintenance serves to reinforce norms. Third, and sociologically most interesting, is sci-fi’s directive function. Directive communications convey information with the goal of affecting attitudes, or, as Stableford puts it, they “command, exhort, instruct, persuade, and urge in the direction of learning and new understanding.” Directive communication challenges the audience, questioning their worldviews.

There are two rival camps of sci-fi fans: those interested in multicultural themes and those who prefer “pulp fiction” with less overt social messages.[\pullthis]

Because norms and values vary across subcultures, forms of sci-fi that serve as maintenance communication for some—reinforcing and legitimating already held values—may seem directive to others who do not hold those values. Indeed, such variation in interpretation of the communicative function is currently prevalent in American and British sci-fi. There are two rival camps of sci-fi fans: those interested in multicultural themes relating to issues such as sexuality, gender identity, and race, and those who prefer “pulp fiction” with less overt social messages or messages supporting the status quo. These groups have even waged resentful public campaigns for specific authors to receive prestigious literary awards.At the heart of this debate are themes related to inequality and stratification. Some readers welcome this type of sci-fi, while others actively oppose what they see as directive communication that they disagree with. Gender and sexuality are prime examples. For instance, the work of recently deceased Ursula K. Le Guin delves deeply into the social construction of gender and sexuality. The plot of her novel Left Hand of Darkness might feel familiar to anyone who has watched Star Trek: the representative of a federation of planets is sent to a planet to convince the population to join the federation. The twist, however, is that the population of the planet in question has no fixed sex; it proves a nearly insurmountable cultural barrier for the visiting representative. Cultural commentators such as Sarah LeFanu and Helen Merrick argue that Le Guin’s fiction is a useful tool for conveying social scientific concepts related to gender and sexuality; others, however, see it as a form of liberal cultural imperialism. More recently, Ann Leckie’s Ancillary Justice and N. K. Jemisin’s Broken Earth series have also caused controversies over their focus on gender and sexuality.

Sci-fi literature that explores racial and ethnic inequality can also be read as directive communication. Here, too, Jemisin’s Broken Earth series is relevant, not only for its racial themes but also because Jemisin is the first African-American to win the prestigious Hugo Award for best sci-fi novel. Perhaps most notable is Octavia Butler’s novel Kindred, which involves a contemporary African-American woman who time travels to 1815. Cultural commentators such as Mark Bould and Elisabeth Anne Leonard have noted how Butler’s work, and sci-fi literature more broadly, highlights issues of colonialism, globalism, and race.

The prevalence of gender and racial themes is somewhat surprising, given that the sci-fi audience is often assumed to be predominantly White and male. Perhaps it is only because of the makeup of the audience that such themes are controversial and seen (sometimes resentfully) as a form of directive communication. Yet they can also be employed by authors and readers to spur what’s known in a phrase from 1960s sci-fi as “grokking”—grasping something foreign or strange by intuition or empathy. Sci-fi is a contested arena with different perspectives on the types of themes and forms of communication people find acceptable, yet for many of us, it has been pivotal in developing our understanding of the social world—how we grok modern society and our place in it.

Resistance and the Art of Words

by Rick Searle

“We live in capitalism. Its power seems inescapable. So did the divine right of kings. Any human power can be resisted and changed by human beings. Resistance and change often begin in art, and very often in our art, the art of words.”

– Ursula Le Guin

Great science fiction is particularly good at showing us that the world we live in needn’t necessarily be so, and it does so with real, messy and multilayered humans (or their alien analogs). Some of the best works not only imagine alternative models to our own society that address some of its primary contradictions, they also attempt to grapple with the likely pitfalls of that alternative’s own solutions. Malka Older’s Centenal Cycle is an excellent, recent example. Neither utopian nor dystopian, the Centenal Cycle attempts to render a plausible version of a future society that, in solving some of the problems of our own times, encounters dilemmas of its own.

The world, as it is, need not be so. The future can be different.[\pullthis]

Two of the planned three books of the Centenal Cycle have already been published. The third novel, State Tectonics, will be released in late 2018. The first two, Infomocracy and Null States, see Older imagining an alternative, global political order. Most of the world’s states have been replaced by “micro-democracy”, polities built from “centenals” (political units of 100,000 individuals) tied together along ideological lines. The group possessing the most centenals becomes the “Supermajority,” granted a few special political powers but little direct control over centenals ruled by alternative governments.The supermajority is chosen through elections held every ten years, and an organization called “Information” establishes the factual truth of the rhetoric deployed in the elections. Information is a sort of politicized mashup of the tech giants we see today.

Well before the 2016 presidential election, Older managed to identify and grippingly novelize issues we see forming the center of political and social debate today. In an era when the cost of production for communication nears zero, how is one able to distinguish truth from falsehood? This imagined system of global micro-democracy, in which “truth” is policed by a single organization, presents a possible solution to our unfettered communication problems, while also revealing the very dangerous pitfalls of making any person or organization the sole arbiter of truth.

Post-election, many of us can see the appeal of imposing editorial responsibilities on platforms such as Google, Facebook, and Twitter, and might even countenance the creation of an organization to police propaganda, purging fake content similar to how these platforms already censor pornography and material that violates copyright. In the Centenal Cycle, Older combines something like this internet policing with organizations promoting transparency in governance, such as Accountability Lab, to which she donated a portion of the proceeds from her novels.

The Centenal Cycle offers a cyberpunk intro to questions around media accountability, the present and future role of internet platforms in deciding what information is easily available to the public, and issues surrounding government accountability and responsiveness to citizens. Yet if the characters running Information are presented as engaging in a heroic struggle against falsehood and sinister efforts to undermine micro-democracy, the reader can’t help but wonder how such powers might be wielded by far less benevolent forces. Freedom under the ever watchful and ubiquitous eye of Information can feel like its opposite. Roz, the protagonist of Null States, admits, on p. 124, “Information is widely hated around the world, for any number of reasons: its power, its ubiquity, its terrifying and useful array of knowledge.”

Further, micro-democracy is not a liberal order. Even if it upholds a set of minimum requirements for human rights, it centralizes speech in the hands of a technocratic elite in a way many might find disturbing. Perhaps Older will address or solve some of her imagined system’s likely pitfalls in the last novel of the Centenal Cycle, but we still live in a world distorted by these contradictions. Today’s students in the human sciences will be tasked with solving the problems of computational propaganda and unresponsive states in an era of global politics, and the Centenal Cycle is among the most engaging ways to teach them that the world, as it is, need not be so. The future can be different.

A Planet Without Gender

by Erica Deadman

The incomparable Ursula Le Guin died recently, and so I’ve been revisiting her famous novel, The Left Hand of Darkness. The story follows Genly Ai, an emissary sent to the planet Gethen to learn about and embed himself in the culture. Gethenians have no fixed gender: they can become male or female during each mating cycle and spend the majority of their time in an androgynous state. The core of the story consists of Ai’s interactions with and reactions to Gethenian culture.

Many have written about Le Guin’s major theme, the effect of sex and gender on society. Here, I would like to discuss the novel’s exploration of gender from a different vantage point: the difficulty cisgendered male protagonist Ai faces in adjusting to Gethen’s lack of gender. Le Guin explores two issues: first, Ai’s struggles to interpret the behavior of people who lack the social frame he’s accustomed to, and second, the misunderstandings that result when Gethenians interact with Ai in unintentionally gender-coded ways. Both cause confusion and frustration for Ai throughout the story.

From the start, Ai is uncomfortable with another character, Estraven’s, androgyny. He can understand, on an intellectual level, what he’s experiencing, but it doesn’t prevent the underlying reaction: “I thought that at table Estraven’s performance had been womanly, all charm and tact and lack of substance, specious and adroit. Was it in fact perhaps this soft supple femininity that I disliked and distrusted in him? For it was impossible to think of him as a woman… and yet whenever I thought of him as a man I felt a sense of falseness, of imposture: in him or in my own attitude towards him?”

Ai’s recollection carries clear elements of misogyny, but it is not simply disdain for a female-presenting person that Ai describes. Rather, it is distrust of one who exhibits both traits that he interprets as feminine and, simultaneously, traits that he interprets as masculine.

Sociologist Judith Lorber’s “Night to His Day: The Social Construction of Gender” can help us understand these reactions. Lorber explains the process by which children are socialized, learning to talk and gesture and move in culturally gender-appropriate ways. As a culture, we have constructed a shared understanding of these methods of self-presentation, “tertiary sex characteristics,” and we use them to categorize people into gendered groups. The process is invisible, the signals “so ubiquitous that we usually fail to note them—unless they are missing or ambiguous. Then we are uncomfortable,” Lorber writes. Even in the androgynous world of Gethen, Ai’s mind strives to sort people according to a gender binary, relying on tertiary characteristics like “Estraven’s performance.” But in a world in which people haven’t learned to do gender as we do, Ai is grasping at false signals, frequently uncomfortable.

As Ai tries to understand this genderless world, Gethenians are baffled by his gendered frame of reference. They are ignorant of the implications of their interactions with him. For example, when Ai falls ill on a physically demanding journey, Estraven inadvertently slights him by attempting to lighten his physical burden. Ai bristles and rants internally, insisting that Estraven is “built more like a woman than a man,” and comparing their relative physical efforts as “a stallion in harness with a mule.” Yet he quickly realizes the unfairness in this attitude: “[Estraven] had not meant to patronize. …He was frank, and expected a reciprocal frankness that I might not be able to supply. He, after all, had no standards of manliness, of virility, to complicate his pride.”

This nicely illustrates scholar Michael Kimmel’s concept of “masculinity as homophobia” which frames masculinity as a rejection of and opposition to femininity (and, by extension, male homosexuality). Consequently, “masculinity as a homosocial enactment is fraught with danger, with the risk of failure… Our efforts to maintain a manly front cover everything we do.” Ai understands that, on Gethen, he is in a gender-free culture, but he is so accustomed to guarding the boundaries of his masculine identity that he cannot readily stop. His swift reaction in defense of that identity, though perplexing to Estraven, is entirely understandable to those who live within the confines of gendered systems.

In showing Ai’s repeated struggles, Le Guin opens readers’ eyes to the pervasiveness of our own culture’s gender binary. It is omnipresent, shaping how we think and interact in ways that are hard to fully grasp until contemplating a completely alien culture. That’s the power of good science fiction, and surely why fans have continued to discover and rediscover this novel decades after its publication.

Beware of Geeks With Good Intentions

by Ijlal Naqvi

Isaac Asimov’s Foundation, a science fiction novel much beloved of geeks, has special resonance among those who imagine themselves as visionaries using advanced knowledge to transform society for the better. When the SpaceX rocket launched in early 2018, its unusual payload even included a copy of the Foundation series as a symbolic gesture.

Foundation is famous for introducing the idea of psychohistory, a mathematical social science that can predict the future. This imagined science comes with appropriate caveats: it can predict the future only for populations (rather than individuals), for a limited number of independent variables, and when performed in secret. Predictive social science has a lot of appeal for people wanting to do good. Within the book, Hari Seldon, the chief intellectual behind psychohistory, predicted that then-thriving galactic empire was going to collapse. He wanted to use psychohistory’s predictions to reduce the ensuing chaos from an expected 30,000 years to 1,000 years. So why do I have such strong reservations about psychohistory? For two reasons: first, core ideas from sociology suggest that a psychohistory could never exist, and, more importantly, even if it could, psychohistory’s normative basis means we must reject it on ethical grounds.

Psychohistory can never exist because the human condition—who we are and what we will do—is not a solvable problem.[\pullthis] Emergence is the idea that systemic characteristics arise organically from the interaction of the system’s parts. Emergent properties (which belong to the system, not the individuals) can’t be determined in advance. You can read more about emergence in organization theory (The Emergence of Organizations and Markets is a good start) and critical realism (Philip S. Gorski’s 2016 Qualitative Sociology article, for instance), but emergence is actually central to sociology: we are not just studying collections of individuals but also the organizations and institutions that arise out of societies in operation. A more hard science-y treatment can be found in complexity theory (as studied at the Santa Fe Institute), which posits that human societies are non-linear systems with multiple, independent actors who co-evolve with their environment. Our world shapes our choices, but we change our world through our actions. Further, how we make sense of the world is not static, but in near-constant flux.

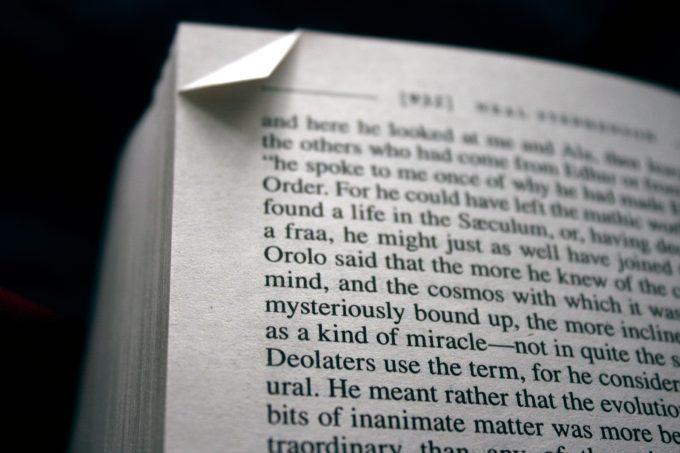

Meaning-making is fundamental to social life. We imbue our lives and actions with meanings that we construct, and these constructions are subject to change over time. I have in mind a version of Anthony Giddens’s “structuration”, but other theoretical formulations fit neatly. Humans think back at you. We are not billiard balls to be sent bouncing around according to immutable laws of motion. Religion, philosophies of legitimate government, family, the good life: these are not constant concepts. Human behavior reshapes itself as our basic categories of meaning making change. The vector space of social life keeps changing because the categories we use to make sense of it are impermanent and because our interventions shape future possibilities.All that aside, in Asimov’s books, psychohistory relies on secrecy and manipulation. The mob whose actions are predicted must be “blind” and without “foreknowledge of the results of their own actions” he writes on p. 120. However, the knowledge that there is a grand plan plays into the characters’ behavior. Comically, one politician with some basic knowledge of psychohistory wonders on p. 121, “I tried never to let my foresight influence my action, but how can I tell?” Later in the series, the psychohistorians use mind control powers to shape human behavior to serve their plan and alter predicted scenarios. Now we begin to see the ethical strain required to justify the implementation of psychohistory in Asimov and beyond.

Good intentions notwithstanding, the paternalism of covertly shaping social futures is profoundly anti-democratic and grossly transgressive upon individual free will and human rights. Without offering a public account of its intentions and methods, any social science taking psychohistory’s capability to predict and shape the future as a model—even if it is in service of the greater good—would have a rotten core.

All this is what I love about science fiction and why I believe it’s profoundly sociological. Despite my opposition to psychohistory and whatever its real-world analogues might be, I value Foundation for provoking challenges to both its core ideas and our own. Novelist Philip K. Dick once defined his genre, sci-fi, as describing worlds that are “possible under the right circumstances,” based on a transformation or dislocation of our current world in such a way that a new society is revealed. At its best, science fiction prompts you to rethink what you know about the world and what the future might hold.

Comments 2

toshiba customer support

September 17, 2018Sociologists tried to understand their career how society works. And the most pressing problems in large parts of the United States may be seen as low employment levels and stable wages in economic data, but are also clear in high rates of depression, drug addiction, and premature death.

Peter Nieckarz

October 2, 2018Good stuff! I published a book chapter on the use of Kurt Vonnegut's Player Piano in an intro to sociology course.