The Algorithmic Rise of the “Alt-Right”

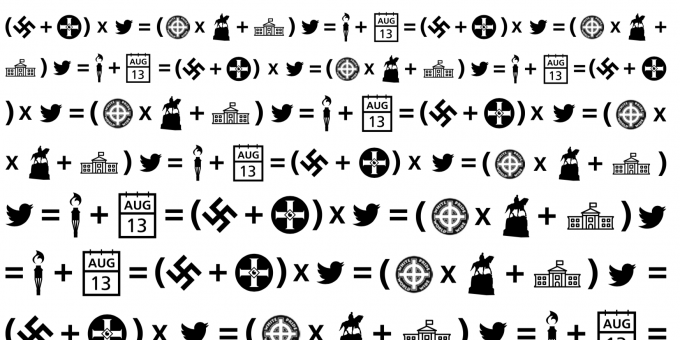

On a late summer evening in 2017, members of the far-right descended on Charlottesville, Virginia with tiki-torches held up in defense of confederate general Robert E. Lee’s statue in what was dubbed a “Unite the Right” rally, which had been organized mostly online. The next day, August 13, White nationalists rallied again and violently clashed with counter protestors. One drove his car into a multiracial crowd, killing one and seriously injuring 19 others. As it has turned out, the events in Charlottesville were a watershed moment in the algorithmic rise of White nationalism in the U.S.

White nationalism has gone “from being a conversation you could hold in a bathroom, to the front parlor,” according to William H. Regnery II. A multimillionaire, Regnery has spent a significant sum of his inherited wealth pushing his “race realist” agenda via a publishing house and the National Policy Institute, a think-tank. When his protégé and grantee, Richard Spencer, coined the new term “alt-right” in 2008, few took notice. Back then, Jared Taylor, publisher of the White nationalist site American Renaissance, said he thought of his own efforts as “just making a racket,” but now he sees himself as part of an ascendant social movement, with Spencer in a lead role. He, along with Jason Kessler, helped organize the rally in Charlottesville.

“I think Tuesday was the most important day in the White nationalist movement,” Derek Black told a New York Times reporter. Black, a former White nationalist, was referring to the Tuesday following the Charlottesville rally, when the current occupant of the White House repeated White nationalist talking points defending the statues of America’s founding slaveholders. In that New York Times interview, Black went on to describe his shock, “… Tuesday just took my breath away. I was sitting in a coffee shop and I thought the news from this was done when I read that he had come back and he said there were good people in the White nationalist rally and he salvaged their message.” It’s certainly not the first time that a sitting president has openly heralded White supremacy from the oval office, but it is the first time that the ideology of White supremacy from both extreme and mainstream sources has been spread through the algorithms of search engines and social media platforms.There are two strands of conventional wisdom unfolding in popular accounts of the rise of the alt-right. One says that what’s really happening can be attributed to a crisis in White identity: the alt-right is simply a manifestation of the angry White male who has status anxiety about his declining social power. Others contend that the alt-right is an unfortunate eddy in the vast ocean of Internet culture. Related to this is the idea that polarization, exacerbated by filter bubbles, has facilitated the spread of Internet memes and fake news promulgated by the alt-right. While the first explanation tends to ignore the influence of the Internet, the second dismisses the importance of White nationalism. I contend that we have to understand both at the same time.

For the better part of 20 years, I have been working with emerging technology and studying White supremacy in various forms of media. In the 1990s, I examined hundreds of printed newsletters from extremist groups and found that many of their talking points resonated with mainstream popular culture and politicians, like Pat Buchanan and Bill Clinton. After that, I left academia for a while and worked in the tech industry, where I produced online coverage of events like the 2000 presidential recount. When I returned to academic research, I did a follow-up study tracking how some of the groups I’d studied in print had—or had not—made it on to the Internet. I spent time at places like Stormfront, the White nationalist portal launched in the mid-1990s, and found that some groups had gained a much more nefarious presence than in their print-only days. And, I interviewed young people about how they made sense of White supremacy they encountered online. About the time I finished my second book in 2008, social media platforms and their algorithms began to change the way White nationalists used the Internet. Now I look at the current ascendance of the alt-right from a dual vantage point, informed both my research into White supremacy and my experience in the tech industry.

The rise of the alt-right is both a continuation of a centuries-old dimension of racism in the U.S. and part of an emerging media ecosystem powered by algorithms. White supremacy has been a feature of the political landscape in the U.S. since the start; vigilante White supremacist movements have been a constant since just after the confederacy lost its battle to continue slavery. The ideology of the contemporary alt-right is entirely consistent with earlier manifestations of extremist White supremacy, with only slightly modifications in style and emphasis. This incarnation is much less steeped in Christian symbolism (few crosses, burning or otherwise), yet trades heavily in anti-Semitism. Even the Islamophobia among the alt-right has more to do with the racialization of people who follow Islam and the long history of connecting Whiteness to citizenship in the U.S. than it does with beliefs about Christendom. Movement members aim to establish a White ethno-state, consistent with every other extremist, White nationalist movement and more than a few mainstream politicians.

This iteration is newly enabled by algorithms, which do several things. Algorithms deliver search results for those who seek confirmation for racist notions and connect newcomers to like-minded racists, as when Dylan Roof searched for “black on white crime” and Google provided racist websites and a community of others to confirm and grow his hatred. Algorithms speed up the spread of White supremacist ideology, as when memes like “Pepe the Frog” travel from 4chan or Reddit to mainstream news sites. And algorithms, aided by cable news networks, amplify and systematically move White supremacist talking points into the mainstream of political discourse. Like always, White nationalists are being “innovation opportunists,” finding openings in the latest technologies to spread their message. To understand how all this works, it’s necessary to think about several things at once: how race is embedded in the Internet at the same time it is ignored, how White supremacy operates now, and the ways these interact.

Building Race into the “race-less” Internet

The rise of the alt-right would not be possible without the infrastructure built by the tech industry, and yet, the industry likes to imagine itself as creating a “race-less” Internet. In a 1997 ad from a now-defunct telecom company, the Internet was touted as a “place where we can communicate mind-to-mind, where there is no race, no gender, no infirmities… only minds.” Then narration poses the question, “Is this utopia?” as the word is typed out. “No, the Internet.” In many ways, the ad reflected what was then a rather obscure document, written by John Perry Barlow in 1996. Barlow, a recently deceased co-founder of the Electronic Frontier Foundation, wrote A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace, a manifesto-style manuscript in which he conceives of the Internet as a “place,” much like the imaginary American frontier in a Hollywood western, that should remain free from control by “governments of the industrial world,” those “weary giants of flesh and steel.” He ends with a grand hope for building “a civilization of the Mind in Cyberspace. May it be more humane and fair than the world your governments have made before.”

While the giddy notion of a “mind-to-mind” utopia online may seem quaint by the standards of today’s “don’t-read-the-comments” Internet, Barlow’s view remains, more than 20 years later, foundational in Silicon Valley. And it informs thinking in the tech industry when it comes to the alt-right. When several tech companies kicked alt-right users off their platforms after Charlottesville, they were met with a vigorous backlash from many in the industry. Matthew Prince, CEO and co-founder of Cloudflare, who reluctantly banned virulently racist site, The Daily Stormer, from his service, he fretted about the decision. “As [an] internet user, I think it’s pretty dangerous if my moral, political or economic whims play some role in deciding who can and cannot be online,” he said. The Electronic Frontier Foundation issued a statement that read, in part, “we believe that no one—not the government and not private commercial enterprises—should decide who gets to speak and who doesn’t,” closely echoing Barlow’s manifesto.Even as the dominant discourse about technology followed the “race-less” imaginary of the sales pitch and the ideology, robust critiques that centered alternative, Afrofuturist visions emerged from scholars such as Alondra Nelson. Critical writing about the Internet has followed, demonstrating the myriad ways race is built into digital technologies. The DOS commands of “master” disk and “slave” disk prompt, Anna Everett points out, reinscribe the master/slave narrative into the level of code. Recent concerns about digital surveillance technologies draw much from pre-digital technologies developed to control enslaved peoples, Simone Browne has explained. Racial categories are coded into drop-down menus and the visual culture of nearly every platform, Lisa Nakamura observes. The nearly ubiquitous white hand-pointer acts as a kind of avatar that, in turn, becomes “attached” to depictions of White people in advertisements, the default “universal” Internet user at the keyboard that becomes part of the collective imagination, Michele White notes. Ideas about race are inextricably linked with the development of tech products, such as “Blackbird” (a web browser) or “Ms. Dewey” (a search tool), André Brock and Miriam Sweeney have written. The $13 billion digital video gaming industry has race coded into its interfaces and has enabled the alt-right, Kishonna Gray observes. The algorithms of search engines and their autocomplete features often suggest racism to users and direct them to White supremacist sites, Safiya Noble documents. And it goes on. Yet despite all this evidence that race is coded into these platforms, the ideology of color-blindness in technology—both in the industry and in popular understandings of technology—serves a key mechanism enabling White nationalists to exploit technological innovations. By ignoring race in the design process and eschewing discussion of it after products are launched, the tech industry has left an opening for White nationalists—and they are always looking for opportunities to push their ideology.

White Nationalists As Innovation Opportunists

The filmmaker D.W. Griffith is recognized as a cinematic visionary who helped launch an art form and an industry. His signature film, Birth of a Nation (1915), is also widely regarded as “disgustingly racist.” Indeed, White supremacists seized upon it (and emerging film technology) when it was released. At the film’s premiere, members of the Klan paraded outside the theatre, celebrating its depiction of their group’s rise as a sign of southern White society’s recovery from the humiliation of defeat in the Civil War. When Griffith screened the film at the White House for Woodrow Wilson, who is quoted in the film, the president declared Birth of a Nation “history writ with lightening.” Capitalizing on this new technology, the KKK created film companies and produced their own feature films with titles like The Toll of Justice (1923) and The Traitor Within (1924), screening them at outdoor events, churches, and schools. By the middle of the 1920s, the Klan had an estimated five million members. This growth was aided by White supremacists’ recognition of the opportunity to use the new technology of motion pictures to spread their message.

Almost a century later, another generation saw that same potential in digital technologies. “I believe that the internet will begin a chain reaction of racial enlightenment that will shake the world by the speed of its intellectual conquest,” wrote former KKK Grand Wizard David Duke on his website in 1998. Duke’s newsletter, the NAAWP (National Association for the Advancement of White People), was part of my earlier study, and he was one who made the transition from the print-only era to the digital era. Duke joined forces with Don Black, another former KKK Grand Wizard, who shared a belief in new technologies for “racial enlightenment.” Together, they helped the movement ditch Klan robes as the costume de rigueur of White supremacy and trade them for high-speed modems.

Don Black created Stormfront in 1996. The site hosted a podcast created by Duke and pushed to more than 300,000 registered users at the site. Don Black’s son recalled in a recent interview that they were a family of early adopters, always looking for the next technological innovations that they could exploit for the White nationalist movement:

“Pioneering white nationalism on the web was my dad’s goal. That was what drove him from the early ’90s, from beginning of the web. We had the latest computers, we were the first people in the neighborhood to have broadband because we had to keep Stormfront running, and so technology and connecting people on the website, long before social media.”

Part of what I observed in the shift of the White supremacist movement from print to digital is that they were very good, prescient even, at understanding how to exploit emerging technologies to further their ideological goals.

A few years after he launched Stormfront, Don Black created another, possibly even more pernicious site. In 1999, he registered the domain name martinlutherking.org, and set up a site that appears to be a tribute to Dr. King. But it is what I call a “cloaked site,” a sort of precursor to today’s “fake news.” Cloaked sites are a form of propaganda, intentionally disguising authorship in order to conceal a political agenda. I originally discovered this one through a student’s online search during a class; I easily figured out the source by scrolling all the way to the bottom of the page where it clearly says “Hosted by Stormfront.” But such sites can be deceptive: the URL is misleading and most of us, around 85%, never scroll all the way to the bottom of a page (all confirmed in interviews I did with young people while they surfed the web). So we see that White nationalists, as early adopters, are constantly looking for the vulnerabilities in new technologies as spots into which their ideology can be inserted. In the mid-1990s, it was domain name registration. The fact that a site with clunky design can be deceptive is due in large part to the web address. One young participant in my study said, “it says, martin luther king dot org, so that means they must be dedicated to that.” To him, the “dot org” suffix on the domain name indicated that a non-profit group “dedicated to Dr. King” was behind the URL.

White supremacists like Don Black understood that the paradigm shift in media distribution from the old broadcast model of “one-to-many” to Internet’s “many-to-many” model was an opening. The kind of propaganda at the site about Dr. King works well in this “many-to-many” sharing environment in which there are no gatekeepers. The goal in this instance is to call into question the hard won moral, cultural, and political victories of the civil rights movement by undermining Dr. King’s personal reputation. Other cloaked sites suggest that slavery “wasn’t that bad.” This strategy, shifting the range of the acceptable ideas to discuss, is known as moving the “Overton window.” White nationalists of the alt-right are using the “race-less” approach of platforms and the technological innovation of algorithms to push the Overton window.

The anything-goes approach to racist speech on platforms like Twitter, 4chan, and Reddit means that White nationalists now have many places beyond Stormfront to congregate online. These platforms have been adept in spreading White nationalist symbols and ideas, themselves accelerated and amplified by algorithms. Take “Pepe the Frog,” an innocuous cartoon character that so thoroughly changed meaning that, in September 2016, the Anti-Defamation League added the character to its database of online hate symbols. This transformation began on 4chan, moved to Twitter, and, by August 2016, it had made it into a speech by presidential candidate Hillary Clinton.

“Turning Pepe into a white nationalist icon was one of our original goals,” an anonymous White supremacist on Twitter told a reporter for the Daily Beast in 2016. The move to remake Pepe began on /r9k/, a 4chan board where a wide variety of users, including hackers, tech guys (and they were mostly guys), libertarians, and White supremacists who migrated from Stormfront gathered online. The content at 4chan is eclectic, or, as one writer put it, “a jumble of content, hosting anything from pictures of cute kittens to wildly disturbing images and language.” It’s also one of the most popular websites ever, with 20 million unique visitors a month, according to founder Christopher “Moot” Poole. “We basically mixed Pepe in with Nazi propaganda, etc. We built that association [on 4chan],” a White nationalist who goes by @JaredTSwift said. Once a journalist mentioned the connection on Twitter, White nationalists counted it as a victory—and it was: the mention of the 4chan meme by a “normie” on Twitter was a prank with a big attention payoff.

“In a sense, we’ve managed to push white nationalism into a very mainstream position,” @JaredTSwift said. “Now, we’ve pushed the Overton window,” referring to the range of ideas tolerated in public discourse. Twitter is the key platform for shaping that discourse. “People have adopted our rhetoric, sometimes without even realizing it. We’re setting up for a massive cultural shift,” @JaredTSwift said. Among White supremacists, the thinking goes: if today we can get “normies” talking about Pepe the Frog, then tomorrow we can get them to ask the other questions on our agenda: “Are Jews people?” or “What about black on white crime?” And, when they have a sitting President who will re-tweet accounts that use #whitegenocide hashtags and defend them after a deadly rally, it is fair to say that White supremacists are succeeding at using media and technology to take their message mainstream.

Networked White Rage

CNN commentator Van Jones dubbed the 2016 election a “Whitelash,” a very real political backlash by White voters. Across all income levels, White voters (including 53% of White women) preferred the candidate who had retweeted #whitegenocide over the one warning against the alt-right. For many, the uprising of the Black Lives Matter movement coupled with the putative insult of a Black man in the White House were such a threat to personal and national identity that it provoked what Carol Anderson identifies as White Rage.

In the span of U.S. racial history, the first election of President Barack Obama was heralded as a high point for so-called American “race relations.” His second term was the apotheosis of this symbolic progress. Some even suggested we were now “post-racial.” But the post-Obama era proves the lie that we were ever post-racial, and it may, when we have the clarity of hindsight, mark the end of an era. If one charts a course from the Civil Rights movement, taking 1954 (Brown v. Board of Education) as a rough starting point and the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement and the close of Obama’s second term as the end point, we might see this as a five-decades-long “second reconstruction” culminating in the 2016 presidential election.Taking the long view makes the rise of the alt-right look less like a unique eruption and more like a continuation of our national story of systemic racism. Historian Rayford Logan made the persuasive argument that retrenchment and the brutal reassertion of White supremacy through Jim Crow laws and the systematic violence of lynching was the White response to “too much” progress by those just a generation from slavery. He called this period, 1877–1920, the “nadir of American race relations.” And the rise of the alt-right may signal the start of a second nadir, itself a reaction to progress of Black Americans. The difference this time is that the “Whitelash” is algorithmically amplified, sped up, and circulated through networks to other White ethno-nationalist movements around the world, ignored all the while by a tech industry that “doesn’t see race” in the tools it creates.

Media, Technology, and White Nationalism

Today, there is a new technological and media paradigm emerging and no one is sure what we will call it. Some refer to it as “the outrage industry,” and others refer to “the mediated construction of reality.” With great respect for these contributions, neither term quite captures the scope of what we are witnessing, especially when it comes to the alt-right. We are certainly no longer in the era of “one-to-many” broadcast distribution, but the power of algorithms and cable news networks to amplify social media conversations suggests that we are no longer in a “peer-to-peer” model either. And very little of our scholarship has caught up in trying to explain the role that “dark money” plays in driving all of this. For example, Rebekah Mercer (daughter of hedge-fund billionaire and libertarian Robert Mercer), has been called the “First Lady of the Alt-Right” for her $10-million underwriting of Brietbart News, helmed for most of its existence by former White House Senior Advisor Steve Bannon, who called it the “platform of the alt-right.” White nationalists have clearly sighted this emerging media paradigm and are seizing—and being provided with millions to help them take hold of—opportunities to exploit these innovations with alacrity. For their part, the tech industry has done shockingly little to stop White nationalists, blinded by their unwillingness to see how the platforms they build are suited for speeding us along to the next genocide.

The second nadir, if that’s what this is, is disorienting because of the swirl of competing articulations of racism across a distracting media ecosystem. Yet, the view that circulates in popular understandings of the alt-right and of tech culture by mostly White liberal writers, scholars, and journalists is one in which racism is a “bug” rather than a “feature” of the system. They report with alarm that there’s racism on the Internet (or, in the last election), as if this is a revelation, or they “journey” into the heart of the racist right, as if it isn’t everywhere in plain sight. Or, they write with a kind of shock mixed with reassurance that alt-right proponents live next door, have gone to college, gotten a proper haircut, look like a hipster, or, sometimes, put on a suit and tie. Our understanding of the algorithmic rise of the alt-right must do better than these quick, hot takes.If we’re to stop the next Charlottesville or the next Emanuel AME Church massacre, we have to recognize that the algorithms of search engines and social media platforms facilitated these hate crimes. To grasp the 21st century world around us involves parsing different inflections of contemporary racism: the overt and ideologically committed White nationalists co-mingle with the tech industry, run by boy-kings steeped in cyberlibertarian notions of freedom, racelessness, and an ethos in which the only evil is restricting the flow of information on the Internet (and, thereby, their profits). In the wake of Charleston and Charlottesville, it is becoming harder and harder to sell the idea of an Internet “where there is no race… only minds.” Yet, here we are, locked in this iron cage.

Recommended Resources

Christopher Bail. 2016. Terrified: How Anti-Muslim Fringe Organizations Became Mainstream. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2016. A sharp, data-driven take on how the brand of extremism that specifically targets Muslims has moved to the center.

Yokai Benkler, et al. 2017. “Study: Brietbart-Led Right-Wing Media System Altered Broader Media Agenda,” Columbia Journalism Review (March 3). The discussion of filter bubbles is beset by an unfortunate both-sides-ism; this piece offers a valuable critique with its empirical take on the predominance of the right-wing.

Alice Marwick and Rebecca Lewis. 2017. “Media manipulation and disinformation online,” Data & Society Research Institute. An important and wide-ranging attempt to understand a variety of online platforms and how they have been manipulated by bad actors.

David Neiwert. 2017. Alt-America: The Rise of the Radical Right in the Age of Trump. Brooklyn, NY: Verso Books. Thorough reporting and concise prose provide a compelling look at the very American nature of the “alt-right.”

Safiya U. Nobel. 2018. Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism. New York: New York University Press. A crucial look at the way search engines and the algorithms that power them reproduce Whiteness and discriminate against people, especially women, of color.

Whitney Phillips. 2015. This is Why We Can’t Have Nice Things: Mapping the Relationship between Online Trolling and Mainstream Culture. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Although Phillips now eschews the term “trolling,” this is a valuable critique and exploration of the portion of Internet culture that provided fertile ground for the rise of the ‘alt-right.’

Samuel C. Woolley and Phillip K. Howard. 2016. “Political Communication, Computational Propaganda, and Autonomous Agents,” International Journal of Communication 10: 4882-4890. An analysis of the manipulation of information by political bots and the politics of an era in which people encounter information architecture through devices and over the Internet of things.