From the "It's Not Just Personal" brochure from the Center for Urban Pedagogy, Black Women's Blueprint, and designers Flora Chan and Abby Chen. http://welcometocup.org/Projects/MakingPolicyPublic/ItsNotJustPersonal

title ix at xlv

Title IX turned 45 this year. This would normally be a cause for celebration, but these are not normal times. Instead, as with many advances in civil rights, we find ourselves reflecting on the backlash, strategizing about how to defend Title IX’s landmark achievements rather than celebrating them.

Title IX, a section of the United States Education Amendments of 1972, prohibits sex discrimination in educational institutions that receive federal funding (which covers the majority of schools). The short statute’s scope has been broadened by Supreme Court decisions and by guidance from the U.S. Department of Education to include sexual harassment and sexual violence. As the survivor and youth-led organization Know Your IX notes, “Under Title IX, schools are legally required to respond and remedy hostile educational environments and failure to do so is a violation that means a school could risk losing its federal funding.” The threat of withdrawn funding supposedly gives the statute its bite, but no institution has ever seen a revocation.The way back to the future goes through the office of Education Secretary Betsy Devos and to the desk of Candace E. Jackson, the lead civil rights official at the Department of Education. To say she’s a reluctant enforcer of gender and racial equity would be massive understatement; like many in this absurdist administration, Jackson is a reverser.

(Nota bene: Jackson is the author of the 2005 book Their Lives: The Women Targeted by the Clinton Machine and arranged the appearance of several women who’ve accused Bill Clinton of sexual assault in a press conference before the October 9, 2016, presidential debate between Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton.)

Studies have consistently found that about one in five female undergraduates has experienced some kind of sexual assault while in college. But to Jackson such numbers are, well, fake news. She made the wild claim that 90% of campus sexual assault accusations “fall into the category of ‘we were both drunk,’ ‘we broke up, and six months later I found myself under a Title IX investigation because she just decided that our last sleeping together was not quite right.’” Jackson later apologized for the remarks, but they were hardly a one-off.

Jackson has also claimed that Title IX assault investigations are not “fairly balanced between the accusing victim and the accused student,” which has led to students being branded rapists “when the facts just don’t back that up.” In most cases, she said, there’s “not even an accusation that these accused students overrode the will of a young woman.” Consequently, Jackson has lent a sympathetic ear to the accused. She even arranged for Sec. Devos to meet with “male rights” groups like Stop Abusive and Violent Environments (SAVE), which bizarrely claimed that “female initiation of partner violence is the leading reason” for domestic violence, and the National Coalition for Men, which posts photographs of “false accusers” in Title IX assault cases online.

Again the facts intrude: the narrative of college girls gone wild, then repentant, is absolutely wrong. The FBI estimates that only between two and 10% of sexual assault allegations are false. And a study released by the Bureau of Justice Statistics found that just 12.5% of surveyed rape survivors on campus reported their experiences to school officials. What this suggests is that sexual violence is grossly underreported, as students face numerous emotional and institutional obstacles to filing a Title IX complaint. Undaunted, Jackson recently wrote a memo directing investigators to reduce inquiries over systemic issues and stopped requiring regional offices to centrally report findings on disproportionate minority discipline or campus sexual assault.

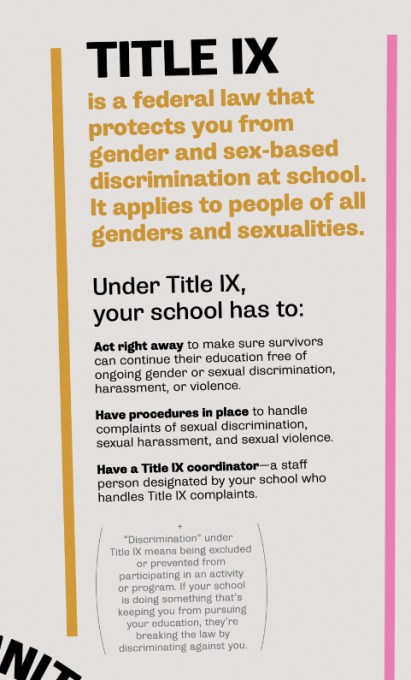

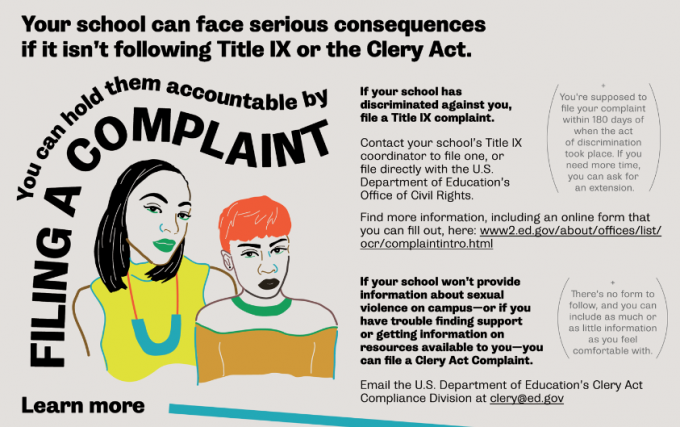

The path to justice is often long and winding, but there is still a path. Its upkeep falls to activists committed to educating, training, organizing and supporting each other. For example, to help student survivors and their allies understand their rights on campus, the Center for Urban Pedagogy (CUP) teamed up with Black Women’s Blueprint and designers Flora Chan and Abby Chen to create “It’s Not Just Personal.” The brightly illustrated guide, which we’ve partially reprinted here, was created for and with students of color and LGBTQ students, and is designed to fill a gap in engaging and culturally relevant information regarding Title IX and the Jeanne Clery Act. (Download and order copies of the poster in its splendorous, full-color glory at welcometocup.org/Projects/MakingPolicyPublic/ItsNotJustPersonal)

And Title IX’s wide influence doesn’t end there. Arguably its biggest impact has been on female participation in sports. In 1971, the year before Title IX was enacted, for example, there were about 310,000 girls and women in America playing high school and college sports; by 2012, there were more than 3,373,000. Given the dramatic increase, you’d expect there to be a corresponding rise in the number of female coaches, but those numbers have dropped over time. Nicole LaVoi points to the stubbornly persistent biases and stereotypes that restrict critical leadership opportunities.

Similarly, Cheryl Cooky discusses how the media cover and portray women’s sports. Despite signs of progress, coverage remains scant and superficial—half-hearted and humdrum reportage rather than once-salacious depictions of female bodies. For fans of female athleticism, the media is seemingly stripped of exclamation marks.

Erin Buzuvis considers Title IX’s bearing on the rights of transgender students—the uncertainty around which has found some students excluded from and others uncertain about their eligibility to participate in athletic competition. In particular, she contrasts Texas’s strict birth certificate criterion with Connecticut’s more inclusive approach in determining gender identity and sport eligibility.

Finally, Ellen Staurowsky writes about how NCAA officials have dubiously leveraged Title IX in their fight against recognizing college athletes as professionals. Such a designation would of course mean that student-athletes would be paid and could potentially unionize, and it would appear that the NCAA will go to troubling lengths to prevent that outcome.

Taken together, these essays illustrate how nearly a half-century of Title IX has dramatically changed the landscape of education and sport, even as we recognize that both arenas remain in flux. –Shehzad Nadeem

- Women Want to Coach, by Nicole LaVoi

- Title IX at 45, Cheryl Cooky

- Where All Kids Can Compete, Erin Buzuvis

- Union Busting and the Title IX Straw Man, Ellen J. Staurowsky

Women Want to Coach

nicole lavoi

During the March Madness of the 2017 NCAA Division-I Women’s Basketball Tournament, University of Connecticut Head Coach Geno Auriemma, arguably the most powerful and successful coach in women’s basketball, was asked why there weren’t more women coaches in the game. His response was forthright: “It’s quite simple. Not as many women want to coach… There’s just too many other choices, that, quite frankly, are better choices for a lot of women.” He’s wrong, but because of his power and privilege, what Geno Auriemma says is often accepted as the truth.

In reality, this “simple” issue is quite complicated. Many scholars, including those in a 2016 book I edited Women in Sports Coaching, have documented numerous barriers to women’s inclusion in team leadership. These include gender and racial stereotypes, homophobia, ageism, sexism, and persistent gendered labor patterns within families, to name just a few of the factors that discourage, impede, or lock women out of coaching. Take, for example, Kara Lawson, an All-American point guard for Pat Summitt at Tennessee, former WNBA player, brilliant basketball mind, and current ESPN commentator. In a recent interview with the New York Times, Lawson said she “wanted to be a coach,” but explained that she’d been denied the opportunity to learn by attending NBA practices because she was considered a “distraction” to the male players. This is to say, women’s “choices” are constrained by and made within a multilevel system of discriminatory beliefs, policies, and practices.

Women’s relative absence from the coaching ranks is all the more glaring when you consider the wide-ranging impact of Title IX for sportswomen. In 1972, one in 27 women played sports. Today, because of Title IX—which created a dramatic increase in opportunities for girls and women—the number of current female sport participants is 1 in 3. However, in the same period, the percentage of college women coached by women dramatically decreased, from over 90% in 1972 to a fairly stable 40% since 2007. The percentage of women coaching men has been stuck at about 2% for 45 years. Women coaches—especially women coaches of color—remain an untapped resource.

The paradox of record female sport participation coupled with a near-low in female coaching it what many call an “unintended consequence” of Title IX. But it is simply not possible that as each new generation of females becomes increasingly passionate about, involved in, and shaped by their sport experience, it becomes simultaneously less qualified or less interested in entering coaching as a profession. Given this, we must ask both whether it matters that women aren’t going into coaching and, of course, why they aren’t.Yes, it absolutely matters that there aren’t many women coaching athletics. First, same-sex role models matter; most girls will never have an opportunity to be coached by a female, while all of their male peers will experience the leadership of a male coach. Second, women coaches challenge outdated stereotypes about gender and leadership. Third, women coaches provide insight, advice, mentorship, and support to help female colleagues navigate and succeed in a male-dominated workplace. Fourth, women coached by women are more likely to go into coaching themselves. And fifth, who is visible in positions of power in sport—one of the most powerful social institutions in the U.S.—communicates who is important, relevant, valued, and competent (and who is not).

As for why, well, only those blinded by privilege are able to say that the mismatch is a “simple” reflection of fact: women don’t want to coach. Geno Auriemma’s take revealed a classic example of how those in power blame those who don’t have power for their own disadvantaged position. Blaming women keeps the status quo in place; the system itself does not get interrogated, scrutinized, or changed. But when we look at the system, we see that women who want to coach are rarely given the opportunity to translate their sport passion, knowledge, and talent into the profession—recall the phenomenally talented Kara Lawson who wanted to find an NBA coach to mentor her, but was denied and told her female presence would be too distracting for the male players. Ageism and sexism combine, too: while men in their 40s, 50s, and beyond are seen as coaches in their prime, women coaches are often fired and rarely rehired in their middle age.

The truth of it is, women want to be coached by women, and women want to coach. The talent of women, including former athletes, has been left untapped to the detriment of generations of athletes—male and female.

Title IX at 45

cheryl cooky

June 2017 marked the 45th anniversary of Title IX, landmark legislation that changed the landscape of high school and collegiate athletics in the United States. Title IX of the Education Amendments states, “No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.” The legislation is most commonly associated with a dramatic growth in girls’ and women’s sports participation, while more recent events signal the ways in which Title IX may precipitate other important changes. One potentially key area is transgender participation in sport, from locker rooms to lacrosse teams; another has seen Title IX employed in a new generation of activism focused on sexual assault and harassment on college campuses (some even suggest that today’s college students will associate Title IX more with consent and gender identity than with athletics). All this demonstrates the resilience and power of Title IX—and its continued relevance at and beyond 45.Five years ago, in commemoration of the 40th anniversary of the legislation, my colleague Nicole LaVoi and I published an article, “Playing but Losing: Women’s Sports after Title IX,” in Contexts. We outlined several persistent forms of inequality in women’s sports, drawing upon sociological research as we considered inequities in media coverage and gender representation in key decision-making positions, including coach and athletic director. Title IX does not legislate either, though we argued that one would reasonably expect, given the millions of girls and women now participating in and excelling at sports (even professional and Olympic-level), we should by now be approaching some semblance of parity in media and management.

Five more years down the line, however, the mainstream sport media continue to ignore the myriad competitive accomplishments of women’s sports (with the exception of major international sports events, like the Women’s World Cup or the Olympics). For example, in longitudinal research that has tracked the quantity and quality of coverage of men’s and women’s sports in televised news and highlight shows over the past 25 years, we found that coverage of women’s sports remains dismally low— no more than 2-3% of the total coverage. In fact, the coverage of women’s sports was lower in 2014 than in 1989 when the study first began. Qualitatively, there have been some important shifts in the way women are represented. We found less content focused on sexually objectifying female athletes or positioning women as the targets of humorous sexualization. Instead, women’s sports were presented in dull and lackluster ways that, when compared to the exciting delivery of men’s sports, was sure to send viewers the message that women’s sports are, well, boring. Asserting that audiences are not interested in women’s sports reinforces the idea that they don’t need much coverage, and, in turn, uninteresting coverage dampens a lot of viewers’ interest.

As far as representation in coaching, Nicole LaVoi finds the representation of women in coaching positions has remained relatively stable over the past 10 years—around 40%. Women continue to encounter structural and cultural barriers to their participation, including sexism and racism, homophobia, the gendered division of labor in families, among other barriers. A recent survey conducted by the Women’s Sports Foundation found women coaches were more likely to state they experienced gender bias on the job, were subject to different expectations than their male counterparts, and believed male coaches were given more professional advantages.

In our forthcoming book, Michael Messner and I argue that these divergent trends illustrate “the unevenness of social change.” Rather than viewing the progression toward gender equality as either an unfinished revolution or a stalled revolution, we show that both changes and continuities in gender in/equality happen simultaneously. If the next 45 years, as we’re seeing now, continues a trajectory of rape culture, harassment, and assault as barriers to participation in higher education and collegiate athletics, the legislation will certainly retain its status as a vital tool for social change.

Where All Kids Can Compete

erin buzuvis

Last winter, even those who don’t generally follow sports heard about Mack Beggs, a transgender boy in Texas who won the state high school championship in girls’ wrestling. Mack identifies as male and would have preferred to compete with other boys. But the state interscholastic athletics league in Texas prohibits students from competing as anything other the sex noted on their birth certificate. Even as science tells us that gender can hardly be reduced to whatever is visible to a doctor glancing considering a newborn’s genitalia, the league refused to accept any other evidence regarding whether Mack is male or female. This disregards the entire notion of gender identity, despite its having been widely validated as a real and salient aspect of an individual’s identity. And it disregards Mack’s own sincere and consistent declaration that his gender identity is male.

In most of the rest of the U.S., Mack would be eligible to compete in boys’ sports. Just six states’ interscholastic athletics associations classify athletes by the gender designation on their birth certificates. Whether Title IX prohibits schools from excluding or assigning transgender athletes because of their birth certificates has yet to be conclusively decided, but even absent a legal requirement more than half of state athletic associations permit transgender athletes to compete according to their gender identity (with some conditions). Even in higher levels of competition, such as NCAA championships and the Olympic Games, Mack would be eligible to compete as a male. This is a notable contrast, since high school sports in Texas purportedly exist to develop character and foster educational values; we should, therefore, expect Texas high school sports to be more inclusive than the Olympics, which showcase elite human athleticism. Instead, Mack could end up excluded from sports altogether—his recent championship win led many to question whether, if he cannot compete with boys, he should be allowed to compete with girls.

Transgender athletes in other states are successfully competing in high school sports. For example, the Hartford Courant recently profiled a Connecticut high school track and field athlete named Andreya Yearwood. Though assigned a male sex at birth, Andreya has a female gender identity and is regarded as female by her family, friends, teachers, coaches, and teammates. Connecticut defers to Cromwell High School’s decision that Andreya is eligible for girls’ sports, because that is consistent with how she is presents and is accepted in all facets of her life. Cromwell officials did not have to consider any criteria other than Andreya’s female gender identity to make this decision; the athletic association does not permit schools to probe athletes’ genitalia, chromosomes, or hormones. Their only role is to determine whether the athlete’s gender identity is “bona fide”—which is to say, that the athlete is legitimately transgender and not seeking an unfair athletic advantage (a problem, it is worth noting, that is entirely hypothetical).Inclusive policies like Connecticut’s make a significant positive difference to athletes like Andreya. Her parents said that her ability to compete as the girl she knows herself to be is liberating, like a “weight lifted off of her shoulder.” Like any high school athlete, she has benefited from the confidence and community that sports develop. These benefits are particularly important to transgender students, who face a higher risk of bullying, isolation, and low body esteem, any of which can undermine a student’s academic progress and emotional well-being. Andreya’s teammates and even her opponents have reportedly greeted her participation with support and respect. And their educational experience is enriched by the opportunity to discover how diverse and unrestrictive the label “female” really is.

When Andreya won two state championship titles earlier this year, some argued that being transgender gave her an unfair advantage. However, this argument wrongly presumes that (anatomically) female athletes are categorically inferior. Though there are generalizable physical differences between male and female bodies, general differences do not conclusively determine that Andreya’s success owes to her anatomically male body. Many nontransgender female athletes compete at or near Andreya’s level, and it is certainly possible that Andreya would be a top-tier athlete even if she had been born into a different body.

Additionally, criticism of transgender athletes’ participation focuses selectively on advantages that may be attributed to one’s transgender status without taking into account myriad of physical, social, and other factors that contribute athletic advantage and disadvantage. There are rarely calls to exclude nontransgender girls whose height, musculature, or other physical characteristics are outside the range of the typical female, nor are there calls to exclude those athletes whose access to economic resources has given them a competitive advantage by allowing them high quality equipment or training. A high school team with more seniors than freshmen is not disqualified, even though the generalizable physical differences between an 18- and a 14-year-old are comparable if not more different than those between anatomical males and females.

But the strongest argument for letting transgender athletes play is hinted at in the text of the Connecticut interscholastic athletic association’s policy itself. It would be “fundamentally unjust,” it says, to preclude a student from participating according to gender identity. The benefits of inclusion to athletes like Andreya, her teammates, and even her competitors simply outweigh whatever harm could occur from athletes’ already unequal skills and advantages. Those who are more upset by a transgender girl beating a nontransgender girl than they would be by the exclusion of that transgender girl reveal their values as discordant with those of interscholastic sport. Implicit in the Connecticut policy is the notion that if the stakes of high school sports are too high to justify making room for athletes like Andreya and Mack, then the stakes should change, not the kids. Texas and its fellow birth-certificate states denigrate the participant-focused mission of high school sports.

Union Busting and the Title IX Straw Man

ellen j. staurowsky

Assertions that college athletes are employees with the right to collectively bargain often trigger arguments about unfairness and ruining the spirit of collegiate sport. Such responses follow high profile legal challenges brought by former and current NCAA Division I football and basketball players seeking changes in rules governing their status as employees with the right to organize (College Athletes Players Association v. Northwestern University), business practices that suppress player value and violate federal anti-trust laws (O’Bannon v. NCAA), access to educational benefits (McCants & Ramsey v. University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill and the NCAA), health and safety (Arrington v. NCAA), and the general regulatory system that traps athletes in a nest of rules that allegedly violates federal anti-trust law (Jenkins v. NCAA). For their part, NCAA Division I athletic directors, commissioners, and officials have branded the dialogue around the employment rights of college athletes as superficial maneuvers by athletes seeking “pay for play.” High school athletes, they argue, could begin to look at college as a way of “making money …as opposed to getting an education,” should collegiate athletes be compensated directly.

Labor scholars will recognize a classic management response to workers’ attempts to influence an array of issues that affect their lives, including length of work week, the manner in which workers are evaluated and controlled by supervisors, workplace health and safety issues, health care and medical coverage, professional development and educational benefits, disability insurance, and fair compensation in relationship to value of the work performed. As the NCAA and other organizations cast the college football and basketball plaintiffs’ grievances as nothing other than the complaints of selfish, greedy, indulgent, ungrateful, and unduly privileged male athletes, Title IX has emerged as an unlikely tool of resistance to the push for professionalization for college athletes. This federal legislation, however imperfect, is credited with increasing opportunities for female athletes in college sport and fostering efforts toward gender equity. And college sport officials have long deployed Title IX as a politically convenient mechanism for sowing misunderstanding, invoking the legislation without nuanced consideration of whether it applies to the situation at hand, under what circumstances it might, and whether its gender equity mandate unilaterally forbids college athletes from being treated as employees. In effect if not intention, athletes’ concerns regarding whether college sport officials have built an industry on unfair labor practices is set up as if it is in opposition to the rights of female athletes to participate in sport under Title IX.This juxtaposition is troubling for several reasons. First, comparing the terms and conditions under which college athletes in the sports of football and basketball play and compete with standards established under common law to define an employee presents a straightforward conclusion: these athletes are employees. They perform a service to their institutions, contribute to the economic benefit of the enterprise, and receive some amount of compensation (generally in the form of tuition benefits). Athletes perform under the supervision and direction of coaching staffs and, from NCAA data and numerous studies of other conferences (Big Ten, PAC 12), it is clear that the time demands of their sport rival those of most full-time workers, often exceeding 40 hours a week. Even 60 hours a week in practice, travel, and play is not uncommon during a given sport’s season.

Second, rather than including female athletes among those who may benefit from changes to an unjust regulatory system around their athletic labor, the argument sets female advancement up as the foil. That is, opponents assert, “if college football and basketball players are recognized as workers,” it will result in the loss of sports and opportunities for women. This very same argument was used when Title IX arrived on the scene in the 1970s. Many wrung their hands and said that applying Title IX to athletic departments would “kill the goose that laid the golden egg”—the legislation, they said, was a threat to profitability of college football and, by extension, to education funding. And yet, since the 1970s, college football has flourished in the United States.

Third, at its foundation, Title IX relies on the characterization of college sports as extracurricular activities. An objective analysis of college sport reveals, though, that it bears little to any resemblance to other “student activities”. The expansion of the regulatory system around college athletes and the surveillance mechanisms put in place to enforce these restrictions present a level of scrutiny and supervision seen nowhere else in voluntary legitimate extracurricular activities. What member of the student paper must abide by a 450-page manual that maps out an elaborate rules structure voted on by authorities with significant conflicts of interests and ties to corporate profit centers? What marching band member is required to disclose personal financial records, car registrations, personal associates and the nature of those relationships, daily activities, or submit to a background check?

Fourth, not all college sports are the same. Some have been developed to compete financially and structurally with major professional leagues (MLB, NBA, NFL) in order to generate revenue and mass audiences, while others are designed to encourage participation. While there is a general assumption that all college sports fall under the umbrella of Title IX, not all physical activity is recognized as being subject to its reach (as has been clarified on numerous occasions when the sport of cheerleading, for example, has been considered).

And fifth, doomsday scenarios in which colleges and collegiate sport organizations are bankrupted by greedy college athletes demanding employee status must be revealed as nothing more than union-busting rhetoric. Many collegiate athletic departments argue that they are already unprofitable, and this framing is readily accepted, though few have bothered to check these claims. Instead, the departments report their finances as needed to maintain non-profit status. Framing this argument as a fight over the viability of college sport further obscures how profit and loss is reported within university and athletic department accounting systems, where a profit can easily become a loss simply through a transfer of funds from department to department across an institution. Not unlike professional sport commissioners and owners who plead financial distress when they undertake negotiations with athletes, conference commissioners, the NCAA president, and athletic directors claim poverty even as their institutions build expansive new athletic facilities and governing bodies negotiate television rights for their games.

In the 21st century, getting clear on how the college sport industry works and what it takes to treat all athletes fairly, equitably, and humanely is a worthy project. Protecting the status quo means protecting a system that has engaged in economic exploitation and socially oppressive practices for far too long. Using Title IX as a means of maintaining that status quo not only misrepresents the fundamental purpose of its civil rights mandate, it actively undermines that mission.