Uncle Sam Wants Them

As an online special, we’re making this article available in its entirety. You may choose to read either the html version or a PDF version.

Throughout most of the 20th century, warring nation-states generally had two options to increase their military strength.

They could create a coalition—as the United States did in World War II—or institute a draft—as it did in Vietnam.

Today, though, countries have a third option. Rent.

Hiring private military corporations, sometimes called private security corporations or private security firms, has fast become a popular way for nations to fight wars.

As a result, much of today’s military workforce isn’t part of the military at all. These military contractors come from across the globe and challenge how we think about nations, states, citizens, and how to exercise accountability in war.

For example, when a Panamanian subsidiary of an American firm hires Colombians to fight Iraqis, which country is responsible for their welfare and answers for their crimes? Which public is likely to mount an anti-war campaign or launch a yellow ribbon drive? And whom do they target? These questions, and the answers to them, have significant consequences for how war gets waged, when it stops, and who’s accountable for it.

These private companies have become major players in all types of modern warfare. Many scholars have focused on the increasing role these corporations play in weak states, especially in Africa, where they are significant domestic players in civil conflict and resource wars. Some, like Stephen Brayton, worry that in failed states, corporations are gaining the “civic and political loyalty” that should belong to the military or police, yet are accountable only to the elites who hire them.

Military companies, though, are as much a tool of the strong as the weak.

the move to private military corporations

Scholars have long thought of fighting wars as something nation-states did through their citizens. Max Weber famously defined the modern state as holding a monopoly over the legitimate use of violence, meaning that only state agents—usually soldiers or police—were allowed to wield force. In contrast to pre-modern Europe, in which local rulers often hired mercenaries to protect their kingdoms, modern states largely put aside the mercenary option in favor of standing armies composed primarily of citizens dedicated (officially, at least) to protecting the entire nation. Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, international law was developed based on this idea of the nation-state.

There were, of course, exceptions to this rule. In the American Revolutionary War the British hired Hessians to fight the colonists, while some mercenaries on the American side became famous war heroes. Even as late as the 1970s European colonial powers hired mercenaries to defeat African “liberation” movements, prompting the United Nations to propose an international treaty against mercenarism. Despite such exceptions, the shift from premodern to modern warfare was marked by the idea that, from here on out, states did—and should—fight wars with their own militaries. Mercenaries appeared as an occasional threat to governments and international order, but only a marginal threat, and one that was waning.

But just as the sun seemed to set on the individual mercenary, it rose on the era of the military corporation. Private military corporations (PMCs) are legal entities that supply governments, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and industry with private soldiers, often referred to as guards or simply “contractors.”

The first modern PMCs can be traced back to the Vietnam War. What made the rise of these organizations possible, explains the Brookings Institution’s P.W. Singer in Corporate Warriors, is the combination of the end of the Cold War, the subsequent downsizing of armies, the availability of smaller high-tech weaponry, and the ideological trend toward outsourcing and privatizing government functions.

Some argue that PMCs are a stronger, more organized form of mercenarism, while others claim they’re a natural extension of the defense industry’s shift from providing goods to providing services. Contractors today provide nearly all the services previously performed by soldiers in war zones, from guarding bases to interrogating prisoners to developing military strategy.

Since the 1990s, PMCs have taken on increasingly larger roles in war and military campaigns. In fact, the ratio of military contractors to soldiers has climbed with each U.S. military intervention since the 1991 Gulf War, such that more private contractors work in the Iraq War than soldiers. And there’s no reason to expect this trend to slow down. Already estimated at more than $100 billion, the PMC market is projected to be worth between $150 billion and $200 billion by 2010.

logistics of pmcs

Governments that contract PMCs have practical reasons for doing so. One is cost. Using contractors instead of public employees saves the government from paying employees’ pensions or peacetime salaries, potentially producing long-term savings. In the short term, however, open-ended contracts and hefty pricetags make contractors more expensive than soldiers. Thus, the true cost of contracting remains an open debate.

Perhaps more important than cost is strategy. PMCs can be rapidly deployed in unanticipated, short-term conflicts.

As such, they can free up soldiers for more sustained military work on other fronts. Moreover, outsourcing “tail-end” jobs, such as laundry and construction, to civilians reduces the demands on a stretched national army.

Many analysts argue a reliance on contractors has allowed the United States to pursue two simultaneous wars despite the 1990s military downsizing. But in countries with weak armies, PMCs can provide a decisive military boost. Sierra Leone is the classic example—it successfully used Executive Outcomes, a South African PMC, to drive back rebels from the capital city in the mid-1990s.

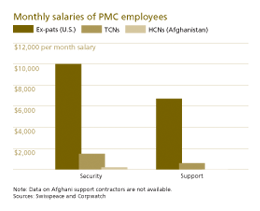

While most PMCs are headquartered in militarily powerful countries such as the United States, Britain, and Israel, a disproportionate number of the PMC workforce itself comes from the global South. According to a survey conducted by the PMC industry’s think tank, the Peace Operations Institute, in U.S. operations only about 10 percent of contracted workers are Americans, while 60 percent belong to the country in which military operations are taking place (Iraqis in Iraq, for example) and 30 percent come from other countries. A Congressional Research Services report reveals those numbers are fairly representative of U.S. efforts in Iraq, with a slightly higher percentage of contractors (65 percent) being Iraqi and about one-quarter being other foreigners.

That last group, called “third-country nationals,” (TCNs) is made up of workers from around the world. They are routinely paid about one-tenth of what their American counterparts earn. Host-country nationals (HCNs) tend to be paid wages commensurate with local jobs.

The international composition of the PMC workforce is notable. Former Haliburton subsidiary KBR alone has employees from 38 different countries working in Iraq. Some third-country nationals—Filipinos and Indians, for example—perform the bulk of support work on American military bases, such as laundry and food service, while others—especially Nepalese, South Africans, and Latin Americans—are hired for security work. The latter usually come from countries with a recent history of counterinsurgency or other claims to military expertise.

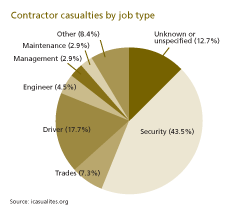

Despite the division between those performing more “tooth-end” and “tail-end” jobs, in war all are vulnerable to attack. The chart above shows the breakdown of contractor casualties in Iraq by job type.

consequences of contractors

The move to PMCs changes the entire spectrum of military labor. It marks a dual shift in the way we think of a military labor force: from public to private, and from domestic to international. This shift affects more than the clothes people wear in war or the languages they speak on base. It undermines old lines of accountability. Military historian Martin van Crevald argues the monopoly over force meant that in war, “it is the government that directs, the army that fights, and the people who suffer.” This may be a dysfunctional relationship, but one with the potential to curb violence nonetheless.

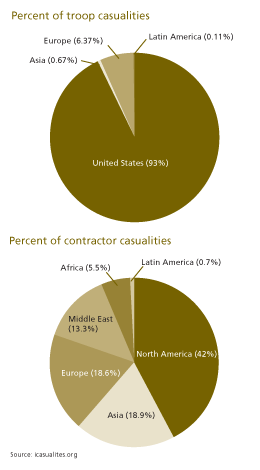

To the extent that the state, the army, and the people all represent the same nation, their fates are interconnected. In democratic countries, “the people” must approve the government’s decision to send the military, and they might retract that approval as military casualties start mounting. Having public, national forces fight wars helps the whole nation experience and internalize their costs. Citizens see “our men and women in uniform” being shipped off to war and the flag-draped coffins when those same soldiers don’t make it home alive. This helps bring the costs of war home to the voting public.

In contrast, using PMCs externalizes the costs of war and outsources accountability. As private employees, contractors don’t leave the same impression on public consciousness that soldiers do, and they’re less amenable to public oversight.

This is truer for some contractors than others. Recent history shows deaths or disappearances of American contractors do make political waves in the United States. Military analysts James Manker and Kent Williams point out that, “Regardless of where the responsibility is placed contractually, [when American contractors are involved] the media reports it as a U.S. casualty, a U.S. captive, or a U.S. wounded without respect to who is at fault.” Indeed, author Jeremy Scahill points out that the 2004 deaths of four Americans working for Blackwater in Fallujah made headlines in the United States for days, and the 2003 capture of three American contractors by FARC guerrillas in Colombia led to ongoing Congressional inquiries throughout their five years of captivity.

Captured or killed foreign contractors don’t receive such treatment. For instance, there was limited political response in the United States when insurgents captured and beheaded 12 Nepalese contractors working in conjunction with the U.S. mission in Iraq. For this very reason, companies sometimes enlist foreign contractors for high-risk or high-visibility roles, such as gunners or pilots. This first became evident to me during my fieldwork on PMCs in Colombia, when I asked a State Department employee why Central Americans were flying U.S.-sponsored counter-drug and counter-insurgency missions there.

“Since these are combat missions, [the U.S. government] didn’t want American pilots flying because of risk and liability,” he responded.

The pattern seems to hold in some other contexts. A Swisspeace report notes that in Afghanistan, security-heavy PMCs such as Blackwater, Dyncorp, and ArmorGroup have some of the highest ratios of third-country nationals. Indeed, some military analysts consider the relative invisibility of foreign contractors to be one of privatization’s key benefits. As a 2005 Rand report notes, the advantages of PMCs are greatest “when policymakers worry less about the safety of non-American contract personnel than about American lives.”

In Iraq, non-American contractors are the hidden casualties of war. Among state-supported coalition troops, Americans make up 93 percent of the casualties. Among contractors, they represent only 43 percent of casualties. The rest are third-country nationals from Europe, Asia, and the Middle East. This percentage would be even smaller if Iraqi contractor deaths were included, but such data are not currently available. Because they aren’t Americans, Iraqi and third-country contractor deaths generally aren’t reported in U.S. newspapers, even though contractors work side-by-side with coalition troops.

Using contractors—especially foreigners—also makes it difficult to determine who’s legally responsible when something goes wrong. This is a problem both for protecting contractors’ welfare and for holding them accountable for crimes. For example, in Iraq there have been widespread reports of PMCs confiscating foreign contractors’ passports and keeping contractors against their will. This led the Defense Department to issue a memorandum in 2006 calling on the companies to clean up their act, but little seems to have changed.

One likely explanation for this inertia is that the foreign contractors are hired through an international web of subcontractors and subsidiaries, effectively deflecting responsibility from any one company.

A Washington Post article from 2004 outlined the contract chain for a group of Indian support contractors: “[The Indian company] Subhash Vijay had hired them to work for Gulf Catering Co. of Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, which was subcontracted to Alargan Group of Kuwait City, which was subcontracted to the Event Source of Salt Lake City, which in turn was subcontracted to KBR of Houston.”

Having such a multinational, highly subcontracted workforce further complicates the already difficult task of holding security contractors legally accountable when they commit crimes. Moreover, without knowing who contractors are or how many are out there, it’s hard even for the state to exercise accountability over them—numerous government reports acknowledge the lack of an accurate count of the number of contractors and subcontractors involved in U.S. military operations.

In some cases, PMCs offer governments strategic flexibility at the expense of full political accountability. For instance, the Defense Department and State Department have effectively used foreign contractors to exceed Congress’s limits on the number of troops involved in a military campaign. (In an effort to contain certain military operations, Congress may place a ceiling, or cap, on the number of soldiers that can be deployed on a mission. But caps generally don’t apply to contractors.)

Congress has tried at times to close this loophole by capping the number of contractors as well, but these caps apply only to Americans, not foreigners. This is the case in Colombia, where the use of foreign military contractors allows U.S. companies to deploy more than the 600-person cap imposed by Congress. This official invisibility of foreign, private participants in such military campaigns makes the conflicts seem smaller and more controllable.

A few groups have tried to increase accountability by reinforcing the political relationships between states and their contractor citizens. In the United States, human rights organizations are advocating for Defense Department contractors to be brought under the military chain of command; this will probably come before the U.S. Supreme Court later this year. The UN’s Working Group on the Use of Mercenaries has pushed PMC recruitment countries to enact stricter domestic legislation to control the flow of their citizens to the PMC market abroad. Some countries see legislation as a way to help their governments control potentially violent citizens. For example, South Africa has enacted strict, but arguably ineffective, laws intended to stop Apartheid-era shock troops from selling their services on the international market.

On the other hand, some developing nations see this market as a solution to the problems of insecurity. For countries like Colombia, the international war market provides a way to employ demobilized paramilitaries and retired soldiers. Whether this is an effective way to reintegrate ex-combatants remains to be seen.

What is clear, however, is that governments currently have neither the authority nor the responsibility over private employees that they have for their own citizen-soldiers operating abroad. The triple challenges of a lucrative international market, weak government controls, and lack of political will to control contractors all lead contractors to operate as free agents. The Blackwater armed guard in Iraq has no more ties to his home state than his compatriot who works at a hotel in Jordan. From the perspective of their governments and their fellow citizens, both are simply international labor migrants.

the rub of controlling pmcs

The Heritage Foundation’s James Carafano argues that nations do have the tools to hold today’s private soldiers, and those who hire them, accountable. In Private Sector, Public Wars, he argues that “Unlike medieval kings [who used mercenaries], modern nations can use the instruments of good governance to control the role of the private sector in military competition.” Among those instruments he lists “[a]n enabled citizenry with ready access to a vast amount of public information.”

But there’s the rub. Which citizenry is he talking about? Under Weber’s ideal, this was never a question—those who fought, those who ordered them into battle, and those who elected the decision-makers were all citizens of the same country. But with privatization and internationalization, there’s no national constituency that automatically identifies with contractors, or with the wars they fight. This poses its own security risk. Privatization removes war one step away from the country that orders it, and internationalization removes it yet another. When the workers of war become more remote and more invisible, the entry barriers to war are lowered. It’s easier to wage war with anonymous soldiers.

Any serious attempts to regulate PMCs will have to deal with this issue. There are many proposals for making the industry cleaner, such as increasing contractor professionalism and creating greater transparency in bids for government contracts. These steps are important for increasing what political scientist Deborah Avant calls “functional control” of the PMC industry, but they do nothing to increase what she calls “political control.” That will only come through laws that help people feel some sense of ownership over the PMC world. Our ability to re-create that sense of public empowerment in this new world will help determine what military privatization means in the long run. It may make the difference between the state hiring out some of the functions of war, and having a private shadow army.

further reading on the web

Shadow Company

Check out the 2007 award-winning documentary, Shadow Company for an inside look at the world of PMCs through personal experiences from Iraq and interviews with PMC staff, owners, and lobbyists, former mercenaries, academics, journalists, and authors. Check out clips from the film on their website, including segments on Sierra Leone, Equatorial Guinea, and the structure of the industry.

Meet the PMCs

Curious who these companies actually are? The Center for Public Integrity compiled a database of more than 150 PMCs with contracts in Iraq and Afghanistan. Their Windfalls of War project includes information about each company (through 2004), the work they’ve been contracted to do, and the value of their contracts (the database documents up to $48.7 billion in Iraq/Afghanistan contracts). You might also look at info from the industry itself: browse privatemilitary.org or the PMC trade association, International Peace Operations Association.

Human Rights and PMCs

The International Committee of the Red Cross and the United Nations High Commissioner of Human Rights further explore the accountability issues raised in the article. These sources discuss the humanitarian and human rights obligations of PMCs and the states that hire them.

Finally, keep an eye on ongoing public commentary on PMCs from The Brookings Institute’s Peter Singer and The Nation’s Jeremy Scahill.

further reading in print

Deborah Avant. The Market for Force (Cambridge University Press, 2005). A political scientist takes on the question of what political and security tradeoffs we can expect with military privatization.

James Jay Carafano. Private Sector, Public Wars: Contractors in Combat—Afghanistan, Iraq, and Future Conflicts (Praeger Security International, 2008). This security analyst believes PMCs are an important military tool that can be adequately controlled by improving the existing system of government contracting.

Jennifer K. Elsea and Nina M. Serafino. “Private Security Contractors in Iraq: Background, Legal Status, and Other Issues.” Congressional Resource Service Report for Congress, July 11, 2007. This report discusses the role and status of third-country nationals, as well as Americans and Iraqis, in the current Iraq campaign.

P.W. Singer. Corporate Warriors: The Rise of the Privatized Military Industry (Cornell University Press, 2003). The author introduces the wide variety of contexts in which PMCs operate and develops a framework for dividing the industry between security and support functions.

United Nations Working Group on the Use of Mercenaries as a Means of Violating Human Rights and Impeding the Exercise of the Rights of People to Self-Determination. Annual Reports. The UN group charged with studying PMCs releases annual reports detailing the labor violations against third-country national contractors and the human rights violations committed by contractors.

Comments 3

Docuticker » Blog Archive » Uncle Sam Wants Them

March 10, 2009[...] Uncle Sam Wants Them Source: Contexts Magazine (American Sociological Association) From press release: The thriving use of private military contractors in place of citizen-soldiers allows nations to externalize the costs of war and outsource accountability during wartime, according to sociologist Katherine McCoy, writing in the winter 2009 issue of Contexts magazine. [...]

Verlinkenwertes (KW 12/09) | Criminologia

March 21, 2009[...] Uncle Sam Wants Them (Contexts Magazine, Volume 8, Issue 1 - Winter 2009, pp. 14-19) [...]

G4S, bandera de conveniencia [Texto en construcción] | Vamos a Cambiar el Mundo

July 17, 2012[...] [...]