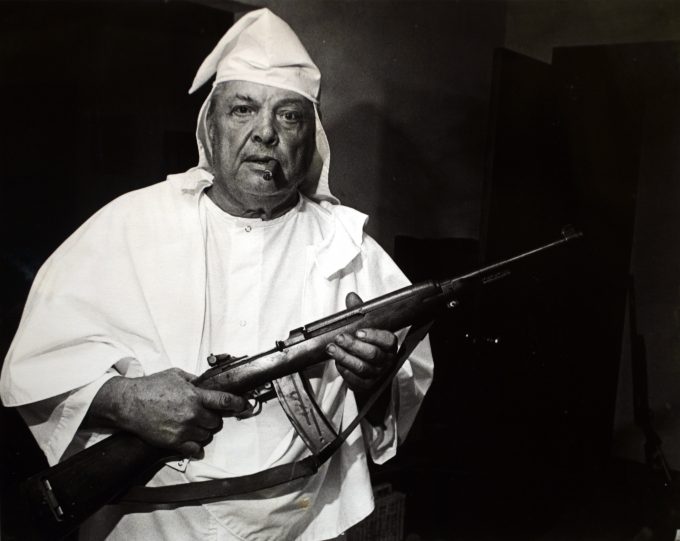

A makeshift memorial to Heather Heyer, killed by a White supremacist in Charlottesville, VA, Aug. 12, 2017. Bob Mical/Flickr CC.

After Charlottesville: A Contexts Symposium

Editors’ Note: In observance of the first anniversary of the “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, Contexts is republishing our collection of essays written in the rally’s aftermath. The second set of essays will be reposted on Friday, Aug. 10. As we write, the city of Charlottesville and the state of Virginia have declared a state of emergency in advance of planned “Unite the Right 2” rallies. The world is watching.

Thousands of sociologists were in Montreal for the annual American Sociological Association (ASA) conference when violence broke out between White supremacists intending to “Unite the Right” and counter-protesters in Charlottesville, Virginia. Counter-protester Heather Heyer was killed and nearly two dozen others sustained injuries, but in his belated second statement, President Donald Trump said that there was “blame on both sides.” Political pundits call this sort of statement “a moral equivalence.” We call it siding with racists. If a person blames both the racists and the people resisting the racists, it suggests that the person has no problem with racists. In a joint editorial effort, we have assembled a group of writers who specialize in research on race, racism, whiteness, nationalism, and immigration to provide sociological insights about how the public, politicians, and academics should process and understand the broader sociohistorical implications of the events in Charlottesville. These writers include two ASA presidents, an editor of the ASA-sponsored journal on race and ethnicity, a professor who received his PhD at the University of Virginia, and two scholars who challenge the political elite and academics to do more to challenge the resurgence of White nationalism in the United States and around the globe.

-Rashawn Ray, Fabio Rojas, Syed Ali, and Philip Cohen

- “‘Hilando Fino’: American Racism After Charlottesville,” Eduardo Bonilla-Silva

- “The Souls of White Folk in Charlottesville and Beyond,” Matthew W. Hughey

- “The Persistence of White Nationalism in America,” Joe Feagin

- “A Sociologist’s Note to the Political Elite,” Victor Ray

- “Are Public Sociology and Scholar-Activism Really at Odds?” Kimberly Kay Hoang

- “Sociology as a Discipline and an Obligation,” David G. Embrick and Chriss Sneed

“Hilando Fino“: American Racism After Charlottesville

by Eduardo Bonilla-Silva

How do we respond to Neo-Nazis marching with torches through Emancipation Park in Charlottesville, parading by a synagogue shouting “Jews will not replace us,” and to a terrorist car attack against crowd of protesters that left anti-racist activist Heather Heyer dead and 19 others injured? How do we respond to a President that immediately after these odious events transpired stated that “many sides” were responsible for the violence and, a few days later, that there “is blame on both sides”? The easy analysis on these matters goes something like this. We have a pocket of racists in the nation that is growing and getting more vocal thanks to Trump’s equivocations and flirtations with racism. Albeit this analysis contains some truth, it ultimately does now allow us to understand the depth of our racial problems. We need to “hilar fino” (do a careful and subtle analysis) to appreciate the weight of racism in contemporary America.First, the largest segment of White America fueling the rise of the “Alt-Right” is also the core of Trump supporters. They are mostly poor and working class Whites who feel left behind. They detest their elite White brethren for their elitism and feel betrayed by their government which, in their view, has violated the rules of the American Dream by helping “undeserving” groups such as Blacks, “illegals,” women, and gays and lesbians. They are people like 35-year-old Matthew Parrott from Paoli, Indiana, described in an article in the Washington Post. Mr. Parrott grew up in a mobile home and attended Indiana University for a semester. There he despised his own folks because they “made fun of my accent” and “called me White trash and hillbilly.”

Second, the class-race anxieties* of this group are not a new development. For instance, Al Ricardi, a taxi driver quoted in Lillian Rubin’s Families on the Fault Line (1994), stated:

Those people, they are hollering all the time about discrimination. Maybe once a long time ago that was true, but not now. The problem is that a lot of those people are lazy. Theirs is plenty of opportunities, but you’ve got to be willing to work hard.

When pressed to define who “those people” are he said:

Aw, c’mon, you know who I am talking about. It’s mostly the Black people, but the Spanish ones, too.

These views are not limited to poor Whites; sociological work documents that middle-class, educated Whites have similar views. The difference is in the way they express their racial views. Elite Whites, as I show in Racism Without Racists, are more refined and cautious and express their views in a “compassionate conservative” manner.

Third, as problematic as the rise of KKK-style racism is, we must be clear that this version of the racial game is not dominant in the nation. The crux of structural racism in contemporary America, even after Trump’s election, is practices and behaviors that are seemingly “color-blind” or “beyond race.” After all, racial order in contemporary America is not maintained primarily through Apartheid-like practices, but through the actions of tolerant, liberal Whites and seemingly non-racial policies.Fourth, politically and analytically, we must be careful not to return to the comfortable yet erratic sport of hunting for the “racists.” This old sociological tradition has not allowed us to appreciate that racial domination is never the product of few bad apples, but the collective effect of the actions and inactions of the many. The more we focus on just poor, uneducated Whites, the less we study and fight against structural racism. Furthermore, many of the clean-cut leaders of the White nationalist movement are educated and come from middle and upper-middle class backgrounds. More significant, albeit poor, uneducated Whites were, and still are, Trump’s most ardent supporters, all Whites supported Trump in the last election with the exception of college-educated White women (51% for Clinton and 46% for Trump). (And let’s not assume that Whites who voted for Clinton were beyond race—all actors in a racialized society are racial subjects and have views mostly fitting of their racial location.)

This is the larger racial context behind Charlottesville and here are some things we should consider doing to fight back. First, we must find ways of dealing with the perceived race-class interests of the White masses. Albeit they are wrong in blaming other similarly oppressed peoples for their plight, we must acknowledge that this is how they feel. Demonizing or ignoring the White masses is not an option if we are still in the business of building the “new society.” Engaging and working politically with them to change their consciousness ought to be the plan of action. Second, focusing only on traditional racism and ignoring hegemonic racism is a huge mistake. The more we focus on the “racists,” the less we deal with the deeper fountain of racism in America. Third, although Whites’ racial perceptions are, as W. I. Thomas would say, “real in their consequences,” they are not static. The support Sanders received from Whites in the last election suggests an economic populist message, if wedded to a clear race and gender politics, might be the key for developing a people’s movement to fight Trumpismo and advance social justice. The task at hand is to address both Alt-Right racism and structural racism and for that a large social movement for racial and social justice is a must.

I know full well most sociologists are content with simply examining the world in various ways, but the times require us to be more action-oriented. Sociologists should provide wonderful analyses and write beautiful books and articles, but at this juncture, we must do much more. We must become sociologically-driven citizens concerned with building a more democratic, inclusive, and just society.

*Far too many analysts and Democrats in general have advanced the storyline that working class Whites are expressing their “class anxieties” and deserve our empathy. While I believe we should be empathetic to all oppressed people, I am not convinced that their anxieties are purely class-based rather than reflective of their racialized, gendered, and homophobic perceptions.

The Souls of White Folk in Charlottesville and Beyond

by Matthew W. Hughey

Daedalus Used Books sits on 4th Street in Charlottesville, Virginia. Intersecting with 4th Street is the downtown pedestrian mall, where Twisted Branch Tea Bazaar and Java Java Café sit only a stone’s throw away. As a graduate student at the University of Virginia (UVA), I wrote good chunks of my dissertation at those cafes, while I read volumes from Daedalus. That graduate research—a comparative ethnographic examination of a White nationalist and White antiracist organization—is now known as White Bound: Nationalists, Antiracists, and the Shared Meanings of Race (2012). It is thus jarringly coincidental that years later, at the same intersection of the downtown mall and 4th Street, a White supremacist would plow their car into a majority White crowd of anti-racist protesters, killing one and injuring many.

In the wake of this tragedy, many have asked: “What would possess a person to do this?” UVA, like surrounding Charlottesville, is a special place full of contradictions and delights. I often describe my time there as “beautifully ugly.” A mix of Jeffersonian traditions (Thomas Jefferson was the founder) and an incubator for elite White male Southern gentility, the University is also home to a hotbed of student activism and Nobel laureate faculty.It was within this context that I came to a comparative study of “White anti-racists” and “White racists.” My germinal thought for the research came after I attended the meetings of a multiracial student group whose aim was to promote “justice and multiculturalism.” White members of this group demonstrated an impressive working knowledge of racism and racial inequality (many today would call them “woke”). Yet, most lived in starkly segregated “White space,” were members of other all-White student organizations, and had constructed majority (if not exclusively) White friend circles.

This latter fact hit me the hardest when, at the conclusion of one meeting, a White member named “Becky” (all names herein are pseudonyms) said to a Black member, “See you at the next meeting!” Puzzled, I asked Becky why she wouldn’t see her fellow member before the next meeting, then two weeks away. “Oh, I don’t really see any of these guys outside of the group,” she said. “What about Shawn, Marcus, and Charlie?” I asked. “Well,” she sheepishly replied, “I do see them quite a bit.” Shawn, Marcus, and Charlie were White.

Upon further investigation of these all-White spaces, both at UVA and within the greater Charlottesville community, I found many ostensibly good and “antiracist” White folk to draw from the same well of racial meaning as the evil or “racist” White folk did. These well-meaning souls often relied upon racist assumptions and beliefs to guide not only their meaning-making about people of color, but how they understood and perform their own Whiteness within all-White spaces.

My time in Charlottesville and UVA afforded me great insights into the mélange of competing White interests and identities, that while multifarious and complex, were all bound together via the pursuit of an ideal form of Whiteness. That ideal form of White identity was built through intra-White performances that entailed being: a kind of messianic or paternalistic savior to people of color; a creative and cosmopolitan “borrower” of the styles and traditions of people of color in order to alleviate the self-perceived dullness spirit of their Whiteness; a person seemingly entitled to any and all knowledge coded as “racial”, and ultimately; a manifestation of biological and/or cultural superiority by virtue of their Whiteness.

Such White intra-racial labor was intensive and often unmarked. And when questioned, many denied the existence of such beliefs and behaviors. This is, on one level, unsurprising. As C. Wright Mills penned in The Sociological Imagination (1959), the sociologist is able to “…take into account how individuals, in the welter of their daily experience, often become falsely conscious of their social positions.”

For instance, even after the events of August 12, 2017, I found many of my White Charlottesville friends denied the racists in their midst. While many from out-of-state did join the fray that day, my newsfeed and communications reverberated with echoes of the Southern narratives of the Reconstruction era—“the racists” are not from there, but are “outside agitators.” “I just don’t believe there are many White supremacists living in the ten square miles that is Charlottesville,” one of my old UVA colleagues stated. A week later, The New York Times wrote:

Through both my lived experience and my research there years ago, I know too well that the dangerous White supremacists are not those with Swastika armbands who yell racial epithets, but the doctors, lawyers, teachers, and police who live and work in a blue dot within a red state. And those souls are seasoned and conditioned in the all-White spaces that Charlottesville all too well provides. Whether overtly marked as “anti-racist” or “nationalist,” or merely as informal friend groups, schools, neighborhoods, and houses of worship, that matters not; all-White spaces appear to serve as a shell for what W. E. B. Du Bois called, in 1920, the “souls of White folk”: “… why will this Soul of White Folk,—this modern Prometheus,—hang bound by his own binding, tethered by a fable of the past?”The searing images of torches and mayhem on the University of Virginia’s iconic lawn and murder in the community that Mr. Jefferson made his home have left many in this state reeling, furious that a group of bigots from beyond the state’s borders have stained a place they revere. Yet those outside agitators only reignited a debate that was inevitably going to return.

Nearly one hundred years later, these all-White spaces appear to possess these souls. Hyper-segregation and intense inequality seems at least a partial answer to Du Bois’s prescient question.

The Persistence of White Nationalism in America

by Joe Feagin

Understanding recent White nationalist views, demonstrations, and riots requires historical and sociological perspectives. Although these White nationalists are often presented as deviant from “American values,” they in fact often exhibit old values and perspectives that are common among many Whites across the country.

Consider our centuries-old White racist history and foundation. The U.S. was founded by leading slaveholders such as George Washington, James Madison, and Thomas Jefferson who operated from a White supremacist and White nationalist perspective in crafting founding documents such as the U.S. Constitution and in developing major political, economic, and legal institutions. Only three human lifetimes have passed since the ostensibly egalitarian Declaration of Independence, yet a document principally authored by the outspoken White supremacist slaveholder Thomas Jefferson. Two human lifetimes have passed since the 13th amendment (1865) to the Constitution ended centuries of human slavery (about 60% of our history). Only one human lifetime has passed since White mobs enforced legal segregation with thousands of lynchings of Americans of color (another 23% of our history).

In that Jim Crow era millions of Whites supported the world’s oldest terrorist group, the violent White nationalist KKK. Over early 20th century decades many White politicians belonged; Senate and House members were often elected with Klan help. Warren Harding was closely linked to the Klan before he was president. Across the country hundreds of White supremacist marches and violent actions—cross burnings, assaults, lynchings—targeted African, Jewish, and Catholic Americans. Only since the 1960s Civil Rights Acts has the U.S. been officially “free” of legally imposed racial discrimination.

Understanding that the extreme oppression of slavery and Jim Crow constitutes all but 17% of our history is essential to comprehending why White racism today remains extensive, foundational, and systemic. By no means has enough time passed or enough effort been taken to eradicate the deep continuing impacts of centuries of systemic racism.

Links between this racist past and the racist present have been obvious in recent decades, those filled with the growth and violent actions of organized White supremacists. The Southern Poverty Law Center has recently counted more than 500 U.S. “hate groups” with specifically White supremacist links, including Klan, neo-Nazi, skinhead, anti-immigrant, and anti-Semitic organizations. An estimated 300,000 Whites are active or passive supporters. Such groups have grown because of supremacists’ obsession with the immigration of people of color and so-called “browning of America,” as well as the election of a Black president in 2008.

Members of White supremacist groups are often implicated in White-racist-framed crimes. One recent report of the Southern Poverty Law Center noted that the modest number of hate crime incidents reported to policing agencies in a given year is likely a fraction of the 195,000 such crimes estimated by experts to be perpetrated annually. In these crimes African and Jewish Americans are often major targets, joined recently by immigrants of color.Contemporary White nationalist groups have made substantial use of internet websites and social media to recruit supporters to White supremacist versions of the dominant U.S. White racial framing. These websites reveal direct ties to our old White-supremacist foundation. The “Stormfront” nationalist website—probably the largest with hundreds of thousands of users and millions of racist posts—has had a portrait labeled “Thomas Jefferson, White nationalist,” with a Jefferson quote that if slavery ends, “the two races, equally free, cannot live in the same government.” The Council of Europe has estimated there are about 4,000 hate-based websites worldwide, with 2,500 in the U.S. Many spread a White-supremacist ideology and themes of White racial violence.

Additionally, many Whites, especially males, are attracted to White supremacist views by playing racist video games online and offline. Many popular video games reproduce for their players images of White dominance in U.S. society’s racial framing and hierarchy. In addition, openly racist commentary utilized by White players of popular video games increases an acceptance of a White racist framing of society similar to that of White nationalist groups.

Another key to understanding the power and persistence of these centuries-old White nationalist groups is that some major aspects of their racist framing of society is not significantly different from that of Whites unsupportive of extreme nationalism. Most ordinary Whites, surveys indicate, hold numerous White-racist views of U.S. racial matters, including their views on African Americans. One Pew survey found that more than 80% of Black respondents reported widespread racial discrimination in at least one societal area. In contrast, a majority of Whites in that poll denied there was significant anti-Black discrimination. A CNN/ORC poll found 61% of Black respondents felt that anti-Black discrimination was serious in their local area, compared to 25% of Whites. Leslie Picca and I have reported on brief semester diaries that 626 White students at numerous colleges and universities kept on racial events they saw around them. Most of these well-educated young Whites recorded racist events, discussions, and performances they encountered—altogether about 7,500 instances of clearly racist events. African Americans appear in a substantial majority of often blatantly racist commentaries, jokes, and performances reported by White students across the country. Moreover, in online research involving interviews with mostly college-educated White men in several regions, sociologist Brittany Slatton found that most openly expressed a negative and racist framing of Black women, especially of their bodies and lifestyles.

Clearly, much historical and contemporary research evidence demonstrates that the White-racist views expressed by White nationalists in current publications and demonstrations are held by many other Whites. Today’s White nationalists are in many ways not radically deviant from the deep reality of White supremacy on which this country was founded, and which is still evident in many areas of U.S. society beyond extremist White nationalism.

A Sociologist’s Note to the Political Elite

by Victor Ray

On August 11-12, 2017, armed White supremacists and Nazis marched to protest of the removal of confederate statues. Their protests culminated in the murder of Heather Heyer, a 32-year-old anti-racist counter-protester. Trump’s response to events in Charlottesville, Virginia was predictably vile: the president claimed “both sides” were responsible for violence. The implied moral equivalence was a clear victory for open White supremacists, their ideology validated by the world’s most powerful office-holder.

Racist dog-whistles—Clinton’s “super-predators” or Reagan’s “welfare queens”—are used by both parties, and everyone knows exactly who was targeted. But, Trump’s campaign punctured the colorblind bipartisan political consensus on race talk that had governed public discourse for decades. Crude, open White supremacy was denounced. Trump violated that consensus with seeming impunity. But it seems that drawing an equivalence between Nazi killers and antifascists is apparently a red line as Republican politicians, business leaders, and even the President’s Committee on the Arts have scrambled to distance themselves from a president who seems incapable of distinguishing between fascists and the rest of us.

Of course, Nazis and White supremacists should and must be fought by any means necessary. I am heartened by the defections of political and business elites, and I cheer with each newly falling confederate monument. But these defections leave me wondering why these business leaders, politicians, and artists were accommodating the White supremacy of this administration in the first place. One message I take from these defections is that these business and cultural leaders were potentially willing to work with anything short of outright Nazism.

There is nothing particularly hidden, or even surprising, about Trump’s tacit acceptance of White supremacists. He inaugurated his campaign claiming Mexican migrants are rapists and murderers, called for violence against nonWhite protestors, and repeatedly instated a ban on Muslims. The slogans “America First” and “Make America Great Again” aren’t that far removed from the White supremacist’s motivating chant of “blood and soil.” And Trump was slow to repudiate former Klansman David Duke during his campaign. Trump’s equivocation surrounding Charlottesville was a difference of degree, not of kind.

Rather than lauding the bravery or moral clarity (isn’t it cute that the Arts and Humanities Committee’s open letter spelled out “resist”?) of those distancing themselves from the administration in the wake of Charlottesville, we should be asking: what took them so long? As Charles Mills points out in The Racial Contract, White supremacy is a political system often misrecognized as a cognitive state. By only recognizing swastika-draped, tiki-torch bearing racists, we miss the ways White supremacy is in the very sinews of U.S. politics. White supremacy has always been mainstream. The electoral college, the dilution of non-White political power through gerrymandering and voter suppression, attacks on affirmative action, disparate lending practices, and residential segregation all contribute to intractable racial inequalities and are, in many cases, more consequential in shaping the lives of people of color than is the far right. One is reminded of Dr. King’s warning in his Letter From Birmingham Jail, where King claimed there was more to fear from White moderates “more devoted to ‘order’ than to justice.” Pointing to Nazis and Klansmen as the source of White supremacy allows for a kind of White absolution.

The response to Charlottesville also calls to mind Kwame Ture (formerly Stokely Carmichael) and Charles Hamilton’s classic definition of institutional racism:

When White terrorists bomb a Black church and kill five Black children, that is an act of individual racism, widely deplored by most segments of the society. But when in that same city—Birmingham, Alabama—five hundred Black babies die each year because of the lack of power, food, shelter and medical facilities, and thousands more are destroyed and maimed physically, emotionally and intellectually because of conditions of poverty and discrimination in the Black community, that is a function of institutional racism…But it is institutional racism that keeps Black people locked in dilapidated slum tenements, subject to the daily prey of exploitative slumlords, merchants, loan sharks and discriminatory real estate agents. The society either pretends it does not know of this latter situation, or is in fact incapable of doing anything meaningful about it.

If politicians and business leaders are serious about fighting Nazis and White supremacy, they will move beyond the profitable (and easy) symbolism of condemning statements and support policies that can provide material resources for people of color. Affirmative action in admissions and hiring, the desegregation of public schools, greatly expanded affordable housing, and the end of a myriad of discriminatory policing practices are just a few of the policy changes that would need to occur to truly dismantle White supremacy.

Are Public Sociology and Scholar-Activism Really at Odds?

by Kimberly Kay Hoang

The White nationalist march in Charlottesville, VA reopened long-standing debates in sociology about the relationship between scholarship and activism. This heated topic is as old as the discipline: to establish sociology as a legitimate (e.g., objective) science, the predominantly White men who made up the first departments in the country pushed “applied” research (often done by women) into the realm of social work (see Mary Jo Deegan’s Jane Addams and the Men of the Chicago School, 1892-1918) and marginalized African American scholars, such as W.E.B. DuBois, who used their research to fight against racial inequality (see Aldon Morris’s The Scholar Denied: W.E.B. DuBois and the Birth of Modern Sociology). In the civil rights era, this topic became central again (see Carol Polsgrove’s Divided Minds: Intellectuals and the Civil Rights Movement), culminating in the establishment of the Society for the Study of Social Problems (SSSP) by a group of activist scholars pushing against “the elitist direction the ASA was following [and] its lack of interest in social problems” (see Jessie Bernard’s 1973 AJS article, “My Four Revolutions: An Autobiographical History of the ASA“).

Writing about the emergence of SSSP, feminist sociologist Jessie Bernard noted that this new organization scared mainstream sociologists—at the time, still largely a group of White men—who worried that activist scholars would give the discipline “a bad name by taking positions on social issues.”Looking at sociology in the era of Trump, it is hard not to feel that history is repeating itself. Take, for instance, the recent backlash on social media against incoming ASA President Mary Romero’s candidate statement. Published in the January/March 2017 issue of American Sociological Association (ASA) “Footnotes,” Romero’s statement makes a case for scholarship and activism in the academy:

We cannot shield ourselves with false notions of “objectivity,” but, as previous presidents have emphasized, ASA actively embraces public engagement and scholar-activism…. ASA must continue to emphasize social justice in sociological inquiry.

Objections to Romero’s statement soon emerged on Twitter—most surprisingly from sociologists who are frequent participants in “public sociology.” Joshua McCabe wrote, “Dear fellow sociologists: Please stop doing this. I just want a professional organization focused on scholarship.” Robb Willer echoed McCabe, writing: “They [sociology and activism] are separate activities with separate goals that should be supported by separate orgs if the discipline wants credibility as a science.” He added later: “I think the discipline risks rep[utation] as unreliable source of expertise if ASA supports activist, esp[ecially] if it’s always left activism.”

Their response to Romero’s statement is one more iteration of these long-standing debates—but, how can we move forward rather than just having the same conversation? In the wake of events like Charlottesville, the question is not “what is best for sociology as a whole?” but who is benefiting and who is suffering as a consequence of our discipline’s current social structure of scholar activism?

I ask these questions because despite this very public protest against Professor Romero’s call for scholar activism in the discipline, Willer (and his co-author Matthew Feinberg) published a February “Wonkblog” op-ed in the Washington Post titled, “The big mistake some anti-Trump protesters could be making.” The authors describe some of the results of their controlled lab experiment designed to answer the question of which left-wing social protest tactics work to influence others. The results published in a white paper suggest that what the authors call “extreme protest tactics”—such as breaking into an animal rights facility and encouraging violence against police—fail to win support for left-wing social movements. In fact, they find that these kinds of protest prompt backlash in the form increased support for the activists’ opponents.

Though the paper as it is published online describes lab experiments with very specific examples of “extreme protest tactics,” Willer’s op-ed makes broad recommendations to anti-Trump protesters and was revived in the wake of right-wing violence in Charlottesville. Echoing intellectuals who warned civil rights movement activists that lunch counter sit-ins and freedom rides would cause a White backlash, Willer and Feinberg caution these protesters to avoid tactics such as interpersonal violence and blocking traffic at the risk of losing support.

Following the events in Charlottesville, prominent sociologists (including the Willer) quickly re-shared Willer’s op-ed on both Twitter and Facebook. While I do not question the empirical contribution of Willer’s research, it is important to ask an epistemological question here. Why do Willer and his team problematize the protests rather than the injustice igniting a response? And why focus specifically on the group of protesters who did not engage in violence?

This also raises a much larger question for sociology: Why are scholars quick to look at the problems with protest without first understanding why folks are protesting to begin with. How can you prescribe solutions to a problem without first understanding the moment we are in?

There is a contradiction in our discipline. Public sociology proponents are supporting a particular market-structure of scholar activism that separates the “resident expert” from the “social activist”. This form of public sociology favors research examining those struggling under and against the effects of power relations (e.g., protesters, poor people) while marginalizing researchers scrutinizing how institutions of power operate to maintain relations of domination (e.g., through institutional racism). This explains how they can denounce the ASA’s commitment to scholar activism while publishing op-eds on their own research regarding tactics of social protest for organizations like Black Lives Matter.But who benefits from his op-ed? Will violent protestors read this, scratch their heads, and change their tactics? No. Will the Trump administration crack down on Willer? No. Will this op-ed demonstrate a broader impact of Willer’s research to tenure and promotion committees? Yes. Does this mean that we as a discipline are in the business of commodifying activism?

These events make me wonder who can legitimately do public sociology without diminishing the discipline’s “credibility as a science.” As ivory tower scholars, we should be reflexive of the ways that our research “informs” front line protestors who assume great risks while we profit and advance our careers as “public experts.” We need to acknowledge our positions (of power and privilege) and recognize Professors Romero’s points regarding false notions of objectivity in our public sociology. How about we first understand the problem (cause of protest in this case) before prescribing a solution (effective modes of protest)? Because really—who benefits from this type of activism at the individual level and at the level of the ASA?

There comes a time when society sinks to such lows that scholars must risk their own standing to stand up for what is right. Climate change researchers have stood up for the truth for the sake of our planet. It’s time sociologists stand against social injustice for the sake of humanity.

Sociology as a Discipline and an Obligation

by David G. Embrick and Chriss Sneed

Since the election of the 45th President of the United States, there has been a rise in not only the number of public hate groups, but also of hate-fueled and violent movements across the nation. Charlottesville, Virginia became the site of one such demonstration in which a young woman, Heather Heyer, was killed, and 19 others were injured by a White supremacist terrorist. Following the tragedy, news outlets reported that the original reason behind the “Unite the Right” rally had to do with the removal of statues linked to the confederacy, namely Confederate General Robert E. Lee. Yet, the use of tiki torches and persistent anti-Semitic and racist chants suggest racism as the underlying motivation for the rally.

Almost 50 years ago, the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders (NACCD) was commissioned to examine the 1967 race riots that were taking place in Los Angeles, Chicago, Newark, and Detroit. Named after NACCD’s chair, Illinois Governor Otto Kerner, Jr., the Kerner Report noted the deepening racial division between Blacks and Whites in the U.S. that was directly related to existing structural inequalities that privileged Whites: “What White Americans have never fully understood but what the Negro can never forget—is that White society is deeply implicated in the ghetto. White institutions created it, White institutions maintain it, and White society condones it.” While diversity has become a mantra from sea to shining sea, the big shiny apple—as Sara Ahmed allows us to imagine—cannot hide the rotting core.

In the last decade, we have seen increasing institutional and interpersonal violence against bodies of color across the nation. Spurred on by a fear of a dark world—one where non-Hispanic Whites will become the minority population—and the dismantling of White spaces, an expansion of terrorism and brutality of all forms has been perpetuated by White[ned] supremacists, White[ned] conservatives, and White[ned] liberals who either desire to maintain the status quo or return back to the ‘good old days’ when it was okay to openly celebrate White supremacy. These inequalities were made visceral as we watched Brown and Black bodies be murdered and watched again as many of their murderers go free, often with excuses that made no sense: Freddie Gray, Malissa Williams, Timothy Russell, Tamir Rice, Jordan Davis, Tanisha Anderson, Aiyana Jones, Eric Garner, Rekia Boyd, Yvette Smith, Renisha McBride, Trayvon Martin, John Crawford III, Michael Brown, John T. Williams, Miriam Carey, Jessie Hernandez, Jonathan Ferrell—the list is long and growing.

The Call for Scholar Activists

Amid these violent, overtly racist/sexist/homo-transphobic times, what role should academics play? While this is not a new question, it remains relevant as many of us wonder whether sociologists and other social scientists have an obligation to be a part of the change we write about, or even whether our respective academic disciplines allow us the opportunity (and reward us) for doing so.

In his 2004 American Sociological Association (ASA) Presidential Address, Michael Burawoy reclaimed that sociology is and—for humanity’s sake—must be more than a realm of theory. Note: we choose to use the word “reclaim” in this instance to recognize the countless voices of scholars of color who currently and historically have taken such position, that the work of sociologists, and the discipline, ought to be woven into the streets and communities from which such theories emerge.

W.E.B. Du Bois, founding father of American sociology, was an advocate for the practical applications of sociological teaching and research. In “My Evolving Program for Negro Freedom,” Du Bois made clear his view on the potential of sociology and the need for both research and action. After regarding his interest in the discipline as part of a “quest for basic knowledge with which to help guide the American Negro” (p. 34), he states:

I realized that evidently the social scientist could not sit apart and study in vacuo; neither on the other hand, could he work fast and furiously simply by intuition and emotion, without seeking in the midst of action, the ordered knowledge which research and tireless observation might give him. I tried therefore in my new work, not to pause when remedy was needed; on the other hand I sought to make each incident and item in my program of social uplift, part of a wider and vaster structure of real scientific knowledge of the race problem in America.

Since Du Bois, other scholars have appealed to the need for more active engagement within struggles for freedom. For example, Black intellectual and sociologist, Dr. Roderick Bush focused much of his work on racial inequality and social transformation. His 2011 article, “Africana Studies and the Decolonization of the U.S. Empire in the 21st Century,” offers a critical approach to productions of knowledge and the potential of scholarly production:

I argue here that the central task of Africana Studies in the 21st century is to engage its faculty, its students, and its various publics in the intellectual and political task of decolonizing the nationalism of empire within the United States, and thus moving toward solidarity with the billions of oppressed people in the world-system whose lives are constrained by the overarching power of the US hegemon.

This position, which expanded well-beyond Africana Studies to the academy more broadly, is echoed throughout his works.

Referenced by Francesca Cancian‘s 1993 article in The American Sociologist, ASA President-Elect Mary Romero also spoke at length about the influence and importance of social engagement within her work. The project outlined in that article, like her recent ASA presentation (a similar symposium talk is available here) about racialized injustices carried out during former sheriff Joe Arpaio’s term, is both a model of dynamic sociological research and how sociologists can reorient themselves to grapple with struggles for justice. This approach was made explicit in her ASA candidate statement in which she wrote: “We cannot shield ourselves with false notions of “objectivity,” but, as previous presidents have emphasized, ASA actively embraces public engagement and scholar-activism. ASA must be prepared to effectively challenge attacks on tenure and academic freedom in higher education. To be relevant and serve our members, ASA must continue to emphasize social justice in sociological inquiry.”

Outside of sociology, activist scholar Angela Davis has extensively called for academics, especially social scientists to participate in struggles for freedom. Her most recent book ends with a charge that “[w]e will have to go to great lengths. We cannot go on as usual. We cannot pivot the center. We cannot be moderate. We will have to be willing to stand up and say no with our combined spirits, our collective intellects, and our many bodies.”

Sociology as a Social and Societal Obligation

We agree with our many esteemed colleagues outlined above that we have a duty as sociologists, social scientists, and researchers, to be active in the communities, institutions, and societies in which we live. We understand the ensuing violence and racist, sexist, and homo/transphobic events, such as that which recently occurred in Charlottesville, Virginia, to be moments in time in which it is essential for scholars to intervene and engage. That said, we point out the Whiteness and White supremacy that is inherent in our discipline as well as educational institutions that marks such work as precarious—and most times dangerous—for scholars who rise to the task. We must be as equally diligent at decolonizing our discipline as well as our societies; we must be as purposeful at standing up to inequalities in our academic departments as well as at hate rallies; we must be active at standing up to racism, sexism, homo/transphobia, and other injustices wherever it may lie.

Comments 15

Dan Morrison

August 25, 2017Wanted to point out an error in Kimberly Kay Hoang's remarks. In this passage: "Willer’s op-ed makes broad recommendations to anti-Trump protesters and was revived in the wake of right-wing violence in Charlottesville, South Carolina." Charlottesville is placed in South Carolina, not Virginia, where it, and a University of Virginia campus, reside.

Letta Page

August 26, 2017Thanks, Dan - I'll make that correction!

Glen McGhee

August 27, 2017Where is conflict sociology in all this? Somehow, one of the main traditions in sociology is missing here. Simmel, Coser, Mills, Collins, especially his "Violence," are now more relevant than ever, right? Thanks.

elianahermione

February 4, 2019If a person blames both the racists and the humans resisting the racists, it indicates that the person has no trouble with racists. In a joint editorial attempt, we've got assembled a group of writers who focus on studies on race, racism, whiteness, nationalism, and immigration to provide sociological insights about how the general public, politicians, and academics have to method and recognize the wider sociohistorical implications of the occasions in Charlottesville University Essay Help assistance UK.

jodiehooper

February 25, 2019Not only students will be stress-free after handing over their assignments to online essay writing services, but the writers also guarantee the achievement of excellent grades. Considering those students who work 6 days a week, definitely find it hard to produce quality work, hence they take too much stress that their official work also suffers. Thus, with some online help, they can reduce their pressure up too much extent top essay writing services UK.

Cathryn Yoder

July 16, 2019Hello!

You Need Leads, Sales, Conversions, Traffic for contexts.org ? Will Findet...

I WILL SEND 5 MILLION MESSAGES VIA WEBSITE CONTACT FORM

Don't believe me? Since you're reading this message then you're living proof that contact form advertising works!

We can send your ad to people via their Website Contact Form.

IF YOU ARE INTERESTED, Contact us => lisaf2zw526@gmail.com

Regards,

Yoder

cattyvince

February 24, 2020Its an amazing post. thanks for sharing this information and keep sharing.

https://oneworldrental.co.uk/laptop-hire

pikachu chu

May 5, 2020I know there will be many difficulties and challenges but I am determined to do it. If it fails then it will also be a lesson for me: shell shockers

Walter Cameron

May 28, 2020It's true that there are a lot of opportunities for everyone in the States, or even in the UK. Not everyone is bad, and not everyone black man in good. But we also have to admit that there is discrimination based on the color of skin in many countries. As an associate of UK Essay Writing Service, I believe that at least the government should support these minorities on the official level. We have an example of the recent incident of the murder of George by a white policemen. Lets see if the government do the justice or not!

Linda Jason

June 9, 2020Whenever an individual condemns the bullies as well as the people who oppose the racism, this means that the person has no problems with the racists. In a collaborative journalistic initiative, we have gathered a group of best essay writing service in the UK writers focused on racism, whiteness, nationalism, and how the general public, policymakers, and scholars have to methodology Charlottesville.

thetec site

September 3, 2020Whenever an individual condemns the bullies as well as the people who oppose the racism, this means that the person has no problems with the racists.

ChasseurDeCougars.com

September 12, 2020Super bien

chrisgail

November 3, 2020It is very interesting. I am very impressed to see the huge bundle of different flowers which are looking very attractive for the visitors. cheap dissertation writing service

Henry

February 27, 2021It is really interesting and helpful for me. I would never forget this post.

Pinaak

July 26, 2022Whenever an individual condemns the bullies as well as the people who oppose the racism, this means that the person has no problems with the racists.