iStockPhoto // DanHenson1

Attending Church Encourages Acceptance of Atheists? No, It’s a Suppression Effect

Does attending church encourage greater acceptance of atheists? In a new open-access article in Political Behavior, we find statistical evidence supporting this conclusion—at least, at first glance.

Now, if you think the idea that attending church encourages greater acceptance of atheists is bonkers, you’re not alone. We do, too.

Let’s back up for a second. We found the result that “attending church encourages greater acceptance of atheists” while chasing down other similarly implausible findings in the rapidly expanding body of research on Christian nationalism (Christian nationalism is a worldview pressing the belief that the United States is rightfully a country of, by, and for Christians). Research on Christian nationalism often concludes that while agreeing with the principles of Christian nationalism is linked to having more conservative, often anti-social preferences (such as supporting harsher policing of racial minorities), more frequent worship attendance is linked to holding more liberal social views (such as demonstrating more warmth toward immigrants).The latter set of claims struck us as implausible because every correlation of attendance and conservatism we have ever seen suggests that more frequent church attendance is associated with more conservative identification and policy stances.

Given these clear patterns, how could one get to a place where it seems like worship attendance is linked to liberal attitudes? Well, we were able to generate the result pretty easily. When independent variables are highly correlated, as are Christian nationalism and worship attendance (staunch Christian nationalists tend to go to church a lot!), including both in a statistical model will reduce the power of the weaker one and sometimes even reverse the direction of the relationship. In other words, although analyses examining the effect of worship attendance by itself suggest that frequent worshippers demonstrate less support for atheists, when we include Christian nationalism in the analysis as well (a very strong predictor of attitudes toward atheists), it suddenly starts to look like the weaker variable (worship attendance) has the opposite effect and now promotes warmth toward atheists.

This is what statisticians call a “suppression effect.” Suppression effects are nothing new. In fact, one recent examination of articles in a top political science journal suggested that about a third of published research relied on a suppression effect without acknowledging its possibility.

One way through this statistical thicket is to develop an explanation for the counterintuitive relationship. For example, Samuel Stroope and his colleagues at Baylor offer a logical explanation for why we might expect frequent worship attenders to be more liberal on immigration even though Christian nationalists tend to be more conservative: Maybe it’s that people who go to church hear messages at church about loving their neighbor, which then counteract nativist messages they receive outside of church settings.

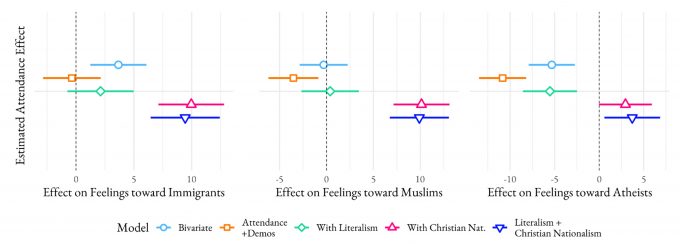

Unfortunately, the data don’t support this explanation. And unless there is compelling evidence to believe otherwise, we should assume that the reversal in the relationship is a statistical artifact. An example of evidence that could lead us to embrace the conclusion that church attendance encourages greater acceptance of immigrants would be evidence of widespread pro-immigrant rhetoric in houses of worship. If true, we could plausibly see attendance linked to more support for immigrants (though not for other groups and public policies that were not addressed).The set of graphs below demonstrates why the seemingly positive relationship between worship attendance and more liberal immigration stances (as well as acceptance of atheists) is actually a suppression effect. The colored shapes and lines indicate the effect of worship attendance on support for three groups: immigrants, Muslims, and atheists. The further they are to the right, the more worship attendance increases support for these groups.

The key takeaway is that the results look very different when Christian nationalism is included in the model. When Christian nationalism is not included in the model (blue, orange, and green), more frequent worship attendance produces little change—or even a reduction—in support for immigrants, Muslims, and atheists. But when Christian nationalism is included in the model (red and purple), it suddenly looks like going to church more frequently significantly boosts support for all three groups.

Figure. The Estimated Attendance Effect on Group/Figure Feelings is a Function of Model Specification

To be sure, some U.S. denominations do encourage inclusive treatment of immigrants. But few Americans report hearing about immigration in their congregations, let alone report hearing positive messages about Muslims or atheists. It is simply unreasonable to think that greater acceptance of atheists follows from people attending church more often. In short, it’s clear that we’re seeing suppression effects.

Scholars working in this area need to stop making unconditional conclusions about worship attendance in the presence of Christian nationalism. Worship attendees themselves tell us that they are conservatives, that they think like conservatives, and that they behave like conservatives. If statistical results seem to contradict these patterns, researchers had better have strong evidence to back up their interpretations. So far, we haven’t seen any make such a convincing claim.

Paul A. Djupe is in the Data for Political Research program at Denison University in Granville, Ohio. He is the coeditor of Trump, White Evangelical Christians, and American Politics: Change and Continuity. Amanda Friesen is in the Department of Political Science at the University of Western Ontario. She directs the Body Politics Lab and is an associate editor at Political Psychology. Anand Edward Sokhey is in the Department of Political Science at the University of Colorado at Boulder. He is a coauthor of The Knowledge Polity: Teaching and Research in the Social Sciences. Jacob R. Neiheisel is in the Political Science department at the University at Buffalo, SUNY. He is the coauthor of a forthcoming book, The Politics of the End: Apocalypticism in America.