What it’s like to be the target of a book ban

In this post, Arlene Stein reflects on the experience of having her book, Unbound: Transgender Men and the Remaking of Identity, targeted for possible removal from a public library. As a bonus, we invited Arlene to share more about this experience in a video interview; you can watch her conversation with blog editor Elena van Stee above. To read more, visit Sociological Forum.

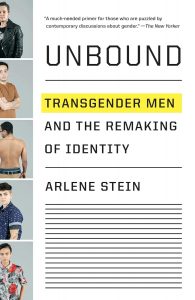

Last month I learned that my book Unbound, a study of transgender men, was targeted for possible removal from the public library by League City, Texas. Its mayor had established a committee to oversee the public library system to determine whether books in its collection violated “community standards.” It selected three books to challenge, and my book was among them.

I had followed with great interest, and more than a little dismay, campaigns to ban books over the past few years. I knew that nearly half of all book bans, according to PEN America, target LGBTQ+ themes. But because I live in the reliably blue state of New Jersey and teach at a university, I felt fairly insulated from it all—until then.

My book had caught the eye of someone who had seen it on display at the city’s Helen Hall Library during Pride Month in June. They reported it to the Community Standards Review Committee on the grounds that it was potentially “obscene.” At a preliminary hearing, members of the review committee argued that my book was “strategically placed” near the children’s section of the library, an unsubstantiated claim. They also warned that my book (and one other) other would “indoctrinate our kids to [the] LGBTQ and transgender lifestyle.”

But why pick on my book? Those who seek to ban books focus on their supposed threat to children, and my book is not a children’s book. Nor is it even vaguely “obscene.” It tells the story of four people in their 20s who decide to modify their bodies to align them more closely with their felt sense of gender. It is a sociological study written for a general audience.

The very act of publicly discussing LGBTQ+ issues threatens families by undermining the ties between parents and children, according to the would-be censors. But if the responses to my book are any indication, the opposite is true.

By offering parents the possibility of better understanding their children, my book, and others like it, contribute to keeping family bonds intact. In fact, I wrote the book with the parents of one of my interview subjects in mind. Bob and Gail Shepherd live in Maine. I met them in the waiting room of a surgeon in Florida as they accompanied their son Ben, who was having his chest masculinized.

They were looking for answers to the questions: why is my child trans? What will his life be like once he transitions? These are the same questions many parents of trans young people are understandably asking. Books like mine help make sense of what can be a scary and confusing process. By all accounts, this is where my book has proven most useful.

In the end, the committee decided to table the matter until they actually read the book. They will then decide whether to “dispose of or destroy” the library’s copy. It’s a chilling thought.“It always starts with book bans,” an acquaintance of mine remarked. The cauldron of fascism began with the public burning of books. Seemingly symbolic attacks on knowledge, we now know, can have catastrophic effects.

The truth is that people will seek out information about controversial issues whether my book, or other such books, are in their library. The question is: will they have access to the kinds of thoughtful knowledge that one can only find in books? Books alone cannot influence people to radically upend their lives, but they can offer clarifying information to those who are suffering, so that they know they are not alone. They can also help people better understand those who are different from them.

By encouraging us to reflect upon and interrogate our taken-for-granted ideas about how the world works, books make our democracy stronger. That, in the end, is precisely what book banners really fear.

Arlene Stein is faculty in the Department of Sociology at Rutgers University. Her research focuses on the intersection of gender, sexuality, culture, and politics. Elena van Stee is a graduate student in the Department of Sociology at the University of Pennsylvania. She studies culture and inequality, focusing on social class, families, and the transition to adulthood.

Comments