Image by padrinan on Pixabay

Covid-19 Impact on Asia and Beyond

Sociology has a lot to say about health. Often sociologists focus on access. Who gets healthcare? Does the healthcare system serve some people better than others? Sociologists also have a lot to say about the consequences of healthcare. Does the financial burden of healthcare weigh more on some than others? Who is left with the task of providing assistance to the elderly and chronically ill?

As of March 31, 2020, nearly every nation on earth will have to deal with the question of consequences. Most directly, they will deal with those who did not survive. They will grieve. They will suffer. The coronavirus will also leave hundreds of thousands, possibly millions of people, with long term pulmonary problems. It may last months, or even years, for many coronavirus patients to recover their complete breathing capacity.

But that is only the beginning. All events of this broad scope will change social relationships. Already, the American economy has been damaged by the coronavirus. Nearly 3.3 million people in the United State filed claims for unemployment benefits – in a single week! This is a record in the history of the United States. We do not need to read our news websites for official data. We can look around our towns and cities to see the massive economic disruption this pandemic has wreaked. The streets are empty, cafes and movie theaters are closed, and millions of productive people sit at home, hoping for the best. The world’s wealthiest and most vibrant economy has buckled, for now.

There are social consequences as well. Already, the Trump administration has approved an emergency relief package where an American family of four with a household income less than $150,000 can receive a stimulus payment of $3400. Other nations have leaned heavily into their own systems for social support. The great question for 2020 will be how the coronavirus impacts our society and politics. Will political leaders use this as an opportunity to improve the functioning of our governments and markets? Or will the epidemic become another excuse for demagoguery and power grabbing?

The articles we present try to answer questions about the social and political impact of the COVID-19 epidemic. They focus on Asian nations and culture. From the center of the epidemic, Huiguang Ren tells us how parenting has changed in light of a city wide shut down near the epidemic “ground zero.” Aggie J. Yellow Horse and Karen L. Leong point to problems when political leaders attach an epidemic to a place like, “Spanish flu” or “China virus.” Average Americans may then direct their anger, even violence, toward people associated with that nation. Already, media outlets report that some Americans have attacked their Asian and Asian American neighbors. Grace Kao and Wonseok Lee raise the possibility that popular culture, in the form of K-pop bands, might be able to counter some of these distressing trends. Perhaps the most eye opening entry in this selection is written by Yifei Li, who teaches at NYU Shanghai. In their essay, Professor Li discusses how the effort to combat disease may become a pretext for the Chinese state to expand its surveillance of citizens.

As time passes, and the global community comes to terms with this epidemic, social scientists will have an increasingly large role to play in the analysis of what went right and wrong, and what might come in the future. These essays are just the tip of the iceberg.

– Rashawn Ray and Fabio Rojas

- ”Coronavirus as Alibi for the Surveillance State” by Yifei Li

- ”Risk Management Regimes and Epidemic Control in East Asia: Lessons from COVID-19” by KuoRay Mao and Lei Zhang

- ”Parenting during the COVID-19 Outbreak: How the Pandemic Impacts Young Children through Parents” by Huiguang Ren

- “Whose Distance from Whom? An Irony of Social Distancing in South Korea” by June Jeon

- ”Rhetoric on COVID-19 Matters for Social Cohesion” by Aggie J. Yellow Horse and Karen J. Leong

- “Can BTS Protect Asian Americans from Xenophobia in the Age of COVID-19?” by Grace Kao and Wonseok Lee

Coronavirus as Alibi for the Surveillance State by Yifei Li

The coronavirus has been a mind-bender on many levels. It is like the canary in the coalmine for all sorts of problems that make up a sociologist’s worst nightmares – de-globalization, planetary anomie, capitalist crisis, racialization, and disinformation wars. There is one other aspect that I am profoundly concerned about, which is the use of COVID-19 as an alibi for building, consolidating, deploying, and expanding the surveillance state.

Those of us at NYU Shanghai are among the first to be affected by the virus’ initial outbreak in China. I have lived through some of the most intense responses to the outbreak since late January. Under the challenges of self-isolation, restricted mobility, citywide checkpoints, and mandatory registration with authorities, I have witnessed the unprecedented growth of the Chinese surveillance state. I have taken up the serendipitous opportunity to be a participant observer of life under the shadows of the surveillance state.

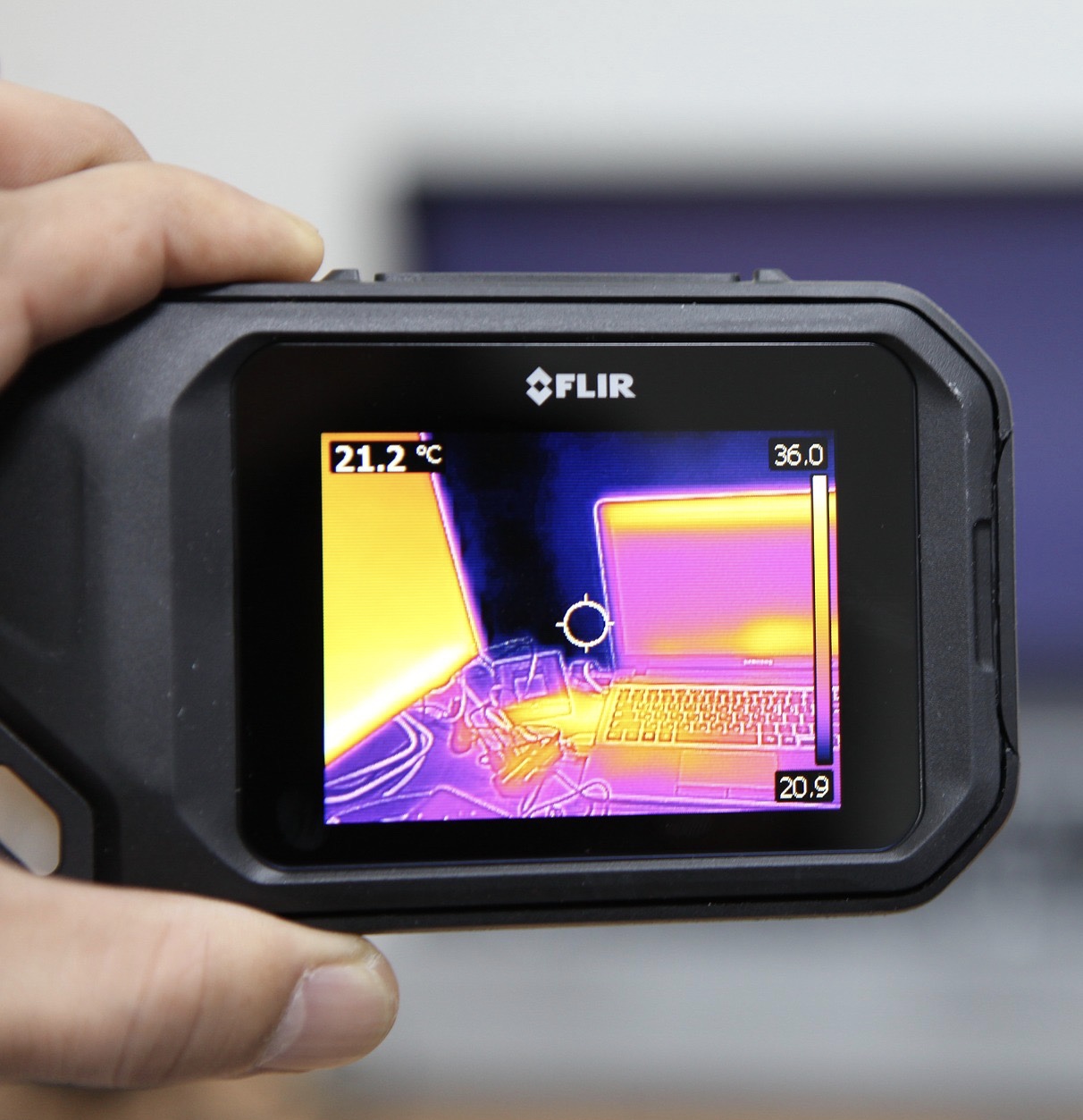

With the ostensible goal of containing the spread of the coronavirus, Chinese authorities have rapidly expanded the scope of the surveillance state by deploying an assortment of digital technologies. In an effort to monitor citizens under home-based medical quarantine, for instance, local officials in Shanghai have been installing wifi-enabled magnetic devices on their doors. Every time the door opens, the magnetic device immediately pushes an automated text message to the head of the neighborhood committee, prompting a house visit. In some neighborhoods, the magnetic trigger is linked to a camera that automatically sends real-time video feeds to the neighborhood head’s smartphone.

Similarly, on the open streets of Shanghai, urban policing now materializes through digital instruments to minimize human-to-human contact. It is commonplace, for instance, for law enforcement officers to remote-control a camera drone to patrol the streets. When they spot a citizen without protective facemask, the drone is maneuvered to approach the unsuspecting citizen, ordering them to put on a facemask or risk being fined.

Most of these policing drones, as is the case with the millions of surveillance cameras throughout the country, are equipped with state-of-the-art facial recognition technologies. Since the coronavirus outbreak started, the Chinese state has invested substantially to improve these technologies so that the high-definition cameras can even recognize citizens wearing facemasks.

The facial recognition data, along with citizens’ travel history, phone location records, online purchase history, smartphone payment reports, and many other data points, all feed into the government’s centralized repository of big data. Applying an undisclosed algorism to this big data, the government assigns color-coded digital “health passes” to ordinary citizens. The green pass suggests low risks of contracting the virus. Its holders are therefore afforded greater mobility. The yellow pass indicates high risks that would disqualify its holders from entering into shopping malls, government service centers, public parks, schools, and even restaurants and cafes. The red pass is reserved for citizens under medical quarantine or treatment.

This constellation of digital technologies is not new. Many have been developed separately under earlier governmental initiatives for the smart city, precision governance, internet of things, and big data advancement. However, during this all-hands-on-deck moment in combating the coronavirus, these digital tools are mobilized all at once, enabling state power to penetrate into private social lives like never before.

Within China, there is no shortage of praise for the government’s iron fist response to the unprecedented public health crisis. Indeed, the state appears to have successfully flattened the curve of new infections in the matter of weeks. Local and national news outlets in China offer overwhelming applause for winning the “war” on coronavirus. Citizens routinely speak of their sense of safety under the watchful eyes of the state. It seems impossible to fault the state for ramping up its surveillance capacity, when the state cites the coronavirus as alibi.

In fact, the most mind-bending element of this development is that the growth of “digital unfreedom” – to borrow the term from Berkeley activist Xiao Qiang – sees little resistance. When national and global attention is all fixated on getting the rapidly evolving coronavirus situation under control, there seems to be little patience to consider the social and moral implications of coercive, invasive state interventions.

The paucity of critical views is chilling. The voices of those who are quarantined behind wifi-magnet-monitored doors have been similarly quarantined from the rest of society. So are those of yellow or red “health pass” holders who have disappeared from public life in the People’s Republic. Citizens who spoke out against the all-encompassing surveillance state are dismissed as sabotaging the nation’s health, if their voices are not altogether purged. None of this comes as surprise, because, by definition, the surveillance state cannot tolerate the canary in the coalmine. Unless we sociologists sing the unsung songs of the canary, the post-coronavirus world may turn out to be chillingly silent.

Yifei Li is an Assistant Professor of Environmental Studies at New York University Shanghai and a Global Network Assistant Professor at New York University. He is co-author (with Judith Shapiro) of China Goes Green: Coercive Environmentalism for a Troubled Planet (2020).

Risk Management Regimes and Epidemic Control in East Asia: Lessons from COVID-19 by KuoRay Mao and Lei Zhang

COVID-19 constitutes a high-consequence global event capable of overwhelming national public health systems and exceeding international harm mitigation capacity. The pandemic represents biological risk at an unprecedented scale and has disrupted the global economy, threatened national security, and may potentially damage the long-term progress of societies. By March 29, 2020, there have been 713,171 confirmed cases of infection and 33,551 deaths reported worldwide. The pandemic poses fundamental risks to the stability of economic and political systems around the world, which will shape how nation-states reformulate the conceptualization of national boundaries, inclusion/exclusion, public safety, and legitimacy in governance. The accumulation of catastrophes and the multiplicity of systematic threats generated by COVID-19 have reshaped state responses to “translocal” connections crucial to a networked global society. As such, a comparative perspective that examines the institutional contexts of national responses towards the pandemic is crucial to our understanding of the dialectical relations between the coronavirus outbreak and the organization of risk governance. In this brief, we examine the institutional factors that have shaped the Chinese state’s responses to the novel coronavirus outbreak up to this point and propose a comparative perspective capable of contextualizing decision-making processes and responses to COVID-19 and future pandemics in different countries.

Risk Management Regimes

As the pandemic continues to spread and political and economic systems experience exponentially compounding shocks in the coming weeks, governments across the world face increasing pressure to maintain social institutions capable of hazards containment and risk reduction while, at the same time, functioning in their respective political and social contexts. To systematically address hazards and insecurities, an effective risk management system should be able to prioritize prevention and preparedness, maintain cross-sectoral coordination, and allocate resources to expedite response and facilitate recovery. China’s first national risk management system was established when the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) outbreak propelled the Chinese central government to promulgate the “Public Health Emergency Response Ordinance” in 2003. The ensuing years saw the modification of the Chinese Constitution in 2004, as well as amendments to national regulations such as the 2013 Prevention and Treatment of Infectious Diseases Law and the 2014 National Environmental Emergency Response Plan. These legislations were designed to create a comprehensive national public health incident management system that streamlines risk prevention, monitoring, and control. The risk management system establishes a direct reporting system between local hospitals and the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to facilitate the swift response of the Chinese National Health Commission to outbreaks.

A Brief Review of the COVID-19 Outbreak and State Responses in China

The first reported case of “pneumonia with unknown causes” appeared in Chinese media in mid-December. Nevertheless, the uncertainty of scientific evidence, the information gap between center and local governments, and the lack of public oversight prevented the implementation of any significant containment measures in the initial stage of the outbreak. The government of Wuhan’s heedless approach had a sudden and complete reversal on January 20 after the 3rd expert panel confirmed direct transmission of the virus, and Chairman Xi ordered all provincial and municipality governments to mobilize for epidemic prevention. A day later, the Chinese State Council officially categorized the novel coronavirus as a Category II infectious disease requiring immediate response. On January 23, the entire municipality of Wuhan entered a lockdown; soon, every Chinese province and autonomous region initiated the highest level of emergency response implementing isolation and quarantine measures. Yet, notably, the direct reporting system in Wuhan did not function until January 24, 28 days after the first report to the municipal government. By then, the epidemic already spread to other Chinese cities. The Chinese central government quickly mobilized national resources to support the public emergency response in affected communities while imposing administrative measures that drastically limited the mobility of the general public to control transmission. Up to the time of writing, according to official reports, COVID-19 has mostly been contained in China. It is sociologically interesting to examine the institutional factors that enabled the Chinese central government to rapidly mobilize nationwide resources and impose quarantine measures in almost all communities. Additionally, how have the formal and informal institutions of governance shaped the Chinese public’s consent or cooperation to the public health emergency responses? The answers to these questions will shed light on the varied and divergent approaches taken by different nation-states in their battle against the global pandemic. As such, we propose the analytical framework below.

Recommendation & Conclusion

To understand the social determinants and consequences of the pandemic, it is essential to examine the institutional factors that constrain and enable state response in risk management. The Wuhan government’s haphazard reactions to the initial outbreak stemmed from the horizontal and vertical compartmentalization of tasks and responsibilities embedded within center-local relations in China. The fragmented institutional structure directly resulted in the local government’s failure to assess the severity of a virus outbreak, to allocate adequate resources for risk prevention, and to coordinate cross-jurisdictional and interagency response. The organization and established practices of the top-down bureaucracy shaped the state’s governing mechanisms, which led to the control of information and a lack of public oversight. Conversely, the organization of the regulatory regime set the stage for the sweeping and forceful responses after January 20. Once the Chinese central government defined COVID-19 as a threat to national security, the state demonstrated nationwide mobilizing power with the support of the public to rapidly allocate resources and build infrastructure to contain the spread of the virus. The establishment of restrictive targets and timelines mobilized the top-down bureaucracy to identify, quarantine, and treat affected populations, which contributed to the downward trend of confirmed cases and deaths in China since February 6. Both the initial negligent and later forceful administrative approaches originated from the organization of formal institutions that are supported by the political ideology and subsequent governmentality of the party-state as well as the informal institutions of cultural traditions at large (Figure 1). Effective state responses in risk management tend to fit the institutional contexts of the specific nations. A comparative analysis of formal and informal arrangements will help elucidate the constraining and enabling factors of national responses in different countries. The understanding will help initiate coordinated actions among states to battle the COVID-19 pandemic in a global risk society.

KuoRay Mao is an Assistant Professor of Sociology at Colorado State University and Lei Zhang is an Associate Professor of Environment & Natural Resources at Renmin University.

Parenting during the COVID-19 Outbreak: How the Pandemic Impacts Young Children through Parents by Huiguang Ren

The outbreak of 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) was an unprecedented public health emergency around the world. Despite the national effort to contain the virus in China, the epicenter of the pandemic, the deadly virus, countrywide quarantine, and subsequent disturbance of normal life have brought widespread panic and anxiety among Chinese publics, and particularly, parents with young children. Given the vulnerability of younger children during the outbreak, parents may be more inclined to socialize their children of the current situation to promote children’s prevention practices, which may further contribute to behavioral and psychological outcomes in children. How might parents socialize their young children during the outbreak? How might parents’ socialization practices contribute to child outcomes during and after the outbreak? These questions are of particular theoretical and practical importance, yet there is no empirical study addressing the questions.

To fill this gap, we interviewed 20 parents with elementary-school-age children in Wenzhou, one of the most impacted cities in China, at the early start of the outbreak (January 24 to January 26, 2020) and towards the end of the outbreak (March 10 to March 16, 2020). Specifically, we aimed to: a) understand Chinese parents’ socialization practices when interacting with their children during the COVID-19 outbreak and b) explore how the acute contextual stressor (i.e., COVID-19 outbreak) may contribute to children’s behavioral and psychological outcomes through the role of parenting.

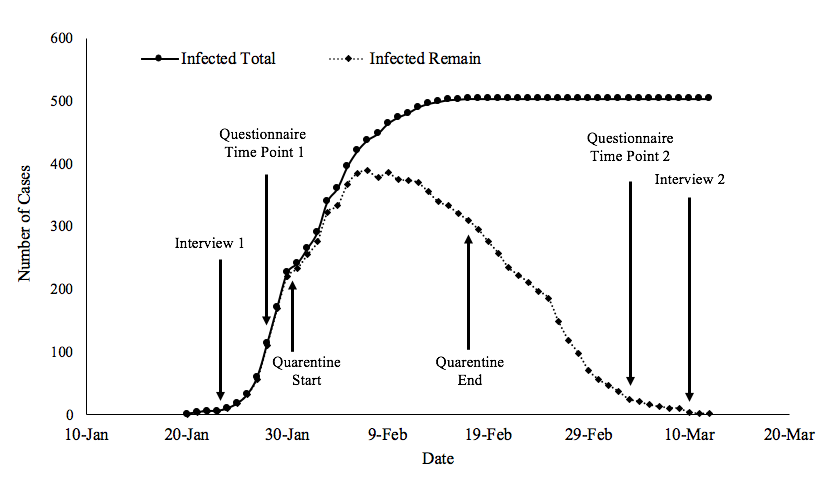

COVID-19 Outbreak in Wenzhou

Wenzhou is one of the most impacted cities in China due to its close business connection with Wuhan, the epicenter of the COVID-19. As of March 12, 2020, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, 2020) in Wenzhou reported a total of 504 infected cases, the largest number among all the cities out of Hubei Province in China. The first COVID-19 case in Wenzhou was identified on January 20, 2020. The local government announced first-level emergency on January 23rd (same day when Wuhan went into lockdown) and implemented stringent quarantine policy on February 1st in response to the rapid spread of the virus. The quarantine ended on February 17th and there was no new confirmed cases or death in Wenzhou after February 22nd.

Semi-Structured Interview with Parents

Semi-structured interview was conducted with 20 parents from lower- to middle-class families with elementary-school-age children in Wenzhou, China at two time points. At the first time point, we asked parents general demographic information and three specific questions: 1) What do you know about coronavirus and how does it impact your daily life? 2) How do you tell your children of the situation and socialize your children in response to the outbreak? 3) How is your child doing right now both generally and specifically regarding prevention practices? At the second time point, we asked parents about: 1) the impact of the outbreak on their families and 2) their children’s behaviors and psychological well-being after the outbreak.

At the first interview, a majority of the parents were aware of the disease, but not all of them expressed serious concern on the situation. Similarly, parents reported three types of strategies when they socialized their children at the early start of the outbreak: proactive socialization, focusing on behavioral prevention, and indifference towards the outbreak. Interestingly, almost all parents who engaged in proactive socialization endorsed inducing fear as a strategy to promote their children’s participation in the prevention practices. At the second interview point, all parents were worried about the pandemic due to not only the chronic anxiety and panic caused by the disease but also financial concerns for the families. Moreover, most parents also expressed optimism towards the current situation in Wenzhou and thought the COVID-19 outbreak was under control.

At the first interview, parents’ increased exposure to the pandemic related information was associated with their use of more fear induction strategies during socialization. Parents who reported more fear induction at the beginning of the outbreak also reported their children’s’ increased compliance and willingness to participate in prevention practices such as wearing face masks, washing hands, and self-quarantine. Interestingly, parents who reported more engagement in the outbreak tended to report more anxiety and reluctance to go back to school from their children. Proactive socialization and using fear induction parenting may promote young children’s willingness to participate and cooperate during emergencies but at the cost of a long-term negative influence on children’s psychological well-being. Efforts should be made to educate lower- to middle-class Chinese parents on more positive and interactive parenting practices during public emergencies.

Huiguang Ren is a Doctoral Student of Psychology at University of Maryland, Baltimore County where they are affiliated with the Culture, Child, & Adolescent Development Lab.

Whose Distance from Whom? An Irony of Social Distancing in South Korea by June Jeon

I was in South Korea at the end of February, when the threat of COVID-19 was already evident in South Korea, but had not quite fully become apparent in the United States. During my short visit to Korea, I was unable to see my family because both my mother and father were confined in hospitals. My mother was staying at a nursing home for cancer treatment and was prohibited to leave the hospital or to meet any visitors. My father was nursing my grandmother who has been at a hospital because of her Alzheimer’s. When COVID-19 became urgent, the hospital gave two choices to my father—go home and don’t come back for a while, or stay with her in hospital, being confined together. He chose the latter. As of March 30th, South Korea had 9,661 cumulative confirmed cases for COVID-19 infection. 395,194 cases had been tested, and 2.4% of them were diagnosed as positive. While the South Korean case is now globally recognized as a successful epidemic management case, the story of social control of people’s mobility is not well known to outsiders.

Sociologists need to contemplate more on asocial aspects of the concept of social distancing. The generalized belief that collective efforts for the social distancing will eventually “flatten” the COVID-19 curve needs to be investigated from a sociological standpoint. There are people who are coerced to be isolated, while others voluntarily practice civic morale by keeping social distance. In South Korea, behind the veil of their success story, a social cost of such control has been disproportionately distributed across the population.

The biggest irony is that, people who are less socially capable of moving around are often enforced to keep the social distance from the rest, whereas people who are in relatively better condition to be socially active are left to voluntarily maintain a social distance. My mother, grandmother, and father all have been strictly prohibited to leave the hospital and forced to practice a self-quarantine regardless of their symptoms or travel history. The only way to escape from the containment is leaving the hospital permanently, which is not a real option for them. My mother still needs radiological treatments; my grandmother and father need a healthcare assistant from the hospital. All of them have not escaped the facility since the third week of the February. Recently, their hospitals announced that they will sue patients if any of them are infected by COVID-19. Patients are double-threatened by a biomedical fear of COVID-19 and a socioeconomic fear of being accused of spreading virus. One doctor in my mother’s hospital told me that it is an inevitable action to minimize the infection; however, it is certainly true that patients—who have to rely on the facility and have no alternative resources—are bearing the greatest social costs.

Patients are the ones who bear a large portion of the burden for group-wide benefits; however, they are also the ones who will be sacrificed at the front line when the infection spreads. It raises the question, from whom are these people enforced to keep their distance? In February 26th, 101 out of 102 patients at Cheongdo-Dae-nam hospital in South Korea were confirmed with COVID-19. In this mental hospital, four to six patients shared a single room and had not been allowed to escape the hospital or meet visitors since early February. Patients were distanced from the entire society; however, they were not allowed to be distanced from each other. As of March 27th, 319 confirmed cases were found in nursing homes and mental hospitals, which is equivalent to 3.3% of entire confirmed cases in South Korea. This is considerably high, given that only less than 0.6% of the entire Korean population are hospitalized in those facilities. Surveillance targets those who are more likely to be sacrificed by the disease—once they are “clean,” it is a success of enforcement; however, when they fail, they just fail together.

The South Korean government did not particularly enforce the isolation of those vulnerable populations together in a facility, nor intend to impose the asymmetric social and health burdens on them. A greater social control comes from voluntary actions by small communities and institutions, pursuing self-interests. People are making ‘rational’ choices in accordance with a science of epidemiology to minimize the spread of virus, and it is remarkable that this ‘rational choices for all’ tends to risk people who are already at risk. There are people who are already isolated from the rest of the society, while they themselves are forced into the same sinking boat. American society also begins to witness group-wide infection of isolated people, such as patients at Evergreen Health hospital in Washington. We will hear more about such cases from nursing homes, asylums, jails, and prisons—and it is on the backs of these already ‘socially distanced’ populations that the curve of the pandemic will be flattened.

June Jeon is a Ph.D. candidate in Sociology at University of Wisconsin-Madison. His research intersects sociology of science, knowledge, and power. His works have been appeared in Social Studies of Science and Engaging Science, Technology, and Society.

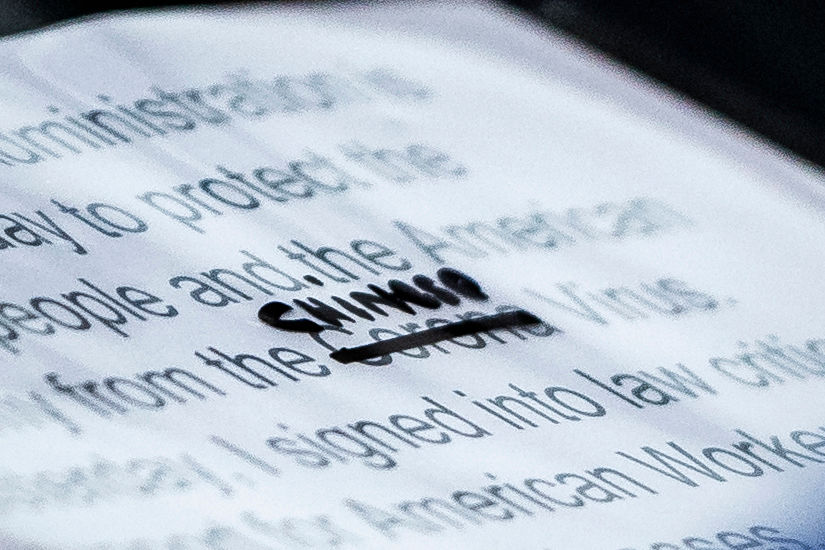

Rhetoric on COVID-19 Matters for Social Cohesion by Aggie J. Yellow Horse and Karen J. Leong

The first reported outbreak of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19, hereafter) occurred in Wuhan, China on December 31, 2020. Subsequently, the first confirmed case of COVID-19 in the United States on January 19, 2020 was identified as an Asian American man who had returned from visiting his family in Wuhan. Since then, political commentaries and media reporting of COVID-19 have “casually” referred to COVID-19 as the “Wuhan virus”, “Chinese virus” or “Asian virus.” Congressman Kevin McCarthy, the U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, and others added the geographic marker to COVID-19; and despite the pushback from other politicians and general public, and against the official guideline by the World Health Organization (WHO), the use of such names continued. On March 11, 2020, Trump switched the labels for COVID-19 as a “foreign virus” and “Chinese virus” in his Oval Office address; and on March 18, 2020, Trump defended his rhetoric at a news conference saying that the phrase is “not racist at all, not at all”. He further added, “It comes from China. That’s why. […] I want to be accurate.” Even though the president tweeted on March 24th, “It is not their [Asian Americans’] fault,” the State Department nonetheless insisted on describe the pandemic as “the Wuhan virus” in a joint G7 statement to the extent that separate statements were issues by the member nations.

A familiar justification for such naming is that this is a common practice; geographic markers commonly have been added to describe the public health outbreak such as “Spanish flu” and “Ebola virus” (Ebola is name of river in Democratic Republic of the Congo). However, the use of such racially-charged and scientifically incorrect rhetoric has real consequences for racial and minority groups. Sonia Shah in a recent Time article has noted that “Right-wing populist leaders have for years singled out foreigners as vectors of crime, terror, and disease, as if they alone posed such threats.” The Trump Administration’s participation in an ongoing blame game taking place between China and the United States about the spread of COVID-19 has only served to fuel racialized scapegoating towards Asian Americans in the United States.

History, moreover, has taught us that many Americans cannot distinguish geographic markers from those of nation nor those of race. Throughout U.S. history, Asian Americans’ heritage has been confused with national affiliation and loyalty — during World War II, Japanese Americans were suspected to be loyal to Japan; during the Korean and Vietnam Wars, Asian Americans were harassed because they were assumed to be Asian, not American. In declaring war on “the Chinese virus,” the U.S. president has rendered U.S. citizens and residents of Asian heritage more vulnerable to harassment and violence.

Xenophobic rhetoric in political statements and media representations about the Chinese origins and Asian transmission of COVID-19 have fueled the rise of racist discrimination against Asian American individuals and communities in the past few months. For example, between January 28 through February 24, 2020, more than 320 cases of xenophobic reactions have been reported including xenophobic reactions against individuals (e.g., barred from establishments, adult harassment/avoidance and child bullying) and against the community (e.g., Chinese/Asian business avoidance and cancellation of events) in mainstream media. Furthermore, there have been more than 650 direct reports of racist and xenophobic incidents against Asian Americans in about one week (from March 18 to March 26) according to the online reporting forum Stop AAPI Hate, organized by Asian Pacific Policy & Planning Council. Asian Americans throughout the United States are reporting microaggressions, discrimination, and violence and hate crimes related to COVID-19. Many Asian Americans, especially recent Asian immigrants and elders, are reporting fear and hesitance in seeking proper medical care with the rise of hate crimes against Asian Americans. Irrational scapegoating based in fear and racial prejudice will further undermine social cohesion and health at a time when social cooperation in slowing down the transmission of the virus is critical.

A positive development emerging from this situation is that some politicians from both parties, members of the media, and even international organizations, are calling out this xenophobic and racist rhetoric for what it is. Their actions remind us that being active members of a community includes taking individual responsibility and involving ourselves in actions that affect us a community. Diverse Americans nationwide are facing specific challenges as result of their age, employment status, race and ethnicity, and combinations of these and other factors. We already are reading accounts of volunteers organizing to ensure that elderly persons have access to basic staples, and school children have access to healthy food during school closures. Let’s remember too that Asian Americans and other groups are facing greater stigmatization due to xenophobia and racism right now, and may feel particularly vulnerable when inhabiting public and commercial spaces. The ihollaback campaign provides tips about interventions bystanders can safely make when witnessing harassment whether it be on public transportation, in shopping areas, or at the doctor’s office [8]. Individual and collective acts of kindness are an important part of upholding our community and the public good— let’s be prepared to be empathetic, compassionate, and engaged.

References

Marquardt, Alex and Jennifer Hansler (2020). US push to include ‘Wuhan virus’ language in G7 joint statement fractures alliance.” CNN Politics, March 26, 2020. CNN. Accessed at https://www.cnn.com/2020/03/25/politics/g7-coronavirus-statement/index.html.

Shah, Sonia (2020). “The Pandemic of Xenophobia and Scapegoating.” Time. February 2. Accessed at: https://time.com/5776279/pandemic-xenophobia-scapegoating/.

[Donald Trump administration labels COVID-19 Pandemic “Made in China,” defend US government’s handling of Outbreak (2020). Associated Press. March 12. Accessed from: https://www.msn.com/en-in/news/world/donald-trump-administration-labels-covid-19-pandemic-made-in-china-defend-us-governments-handling-of-outbreak/ar-BB114XNW.

Jeung, Russell, Gowing, Saras, and Kara Takasaki (2020). “News Accounts of COVID-19 Xenophobia: Types of Xenophobic Reactions, January 28 – February 24, 2020.” Asian Pacific Policy & Planning Council & Chinese for Affirmative Action. Assessed from: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1gkrjw4tfOQLoF_T2YztgExtzexGi0jNX/view.

Kandil, Caitlin Y. (2020). “Asian Americans report over 650 racist acts over last week, new data says.” Assessed from: https://www.nbcnews.com/news/asian-america/asian-americans-report-nearly-500-racist-acts-over-last-week-n1169821.

Asian Americans Advancing Justice (AAAJ) (2020). “StandAgainstHatred: Database of Hate Crime Reports.” Assessed from: StandAgainstHatred.org.

Tavernise, Sabrina and Richard A. Oppel Jr. (2020). “Spit On, Yelled At, Attacked: Chinese-Americans Fear for Their Safety.” Assessed from: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/23/us/chinese-coronavirus-racist-attacks.html.

Public Access Design (2017). Show Up. Your Guide to Bystander Intervention. The Center for Urban Pedagogy. Accessed from: www.ihollaback.org/app/uploads/2016/11/Show-Up_CUPxHollaback.pdf.

Aggie J. Yellow Horse is an Assistant Professor of Asian Pacific American Studies and Justice and Social Inquiry in the School of Social Transformation at Arizona State University. Karen J. Leong is an Associate Professor of Women and Gender Studies and Asian Pacific American Studies in the School of Social Transformation at Arizona State University.

Can BTS Protect Asian Americans from Xenophobia in the Age of COVID-19? By Grace Kao and Wonseok Lee

It may not be obvious what BTS, the biggest K-Pop group ever, has to do with the perception of Asians and Asian Americans amid the novel Coronavirus or COVID-19 pandemic. Allow us to explain.

On March 7, 2020, Billboard listed BTS (Bangtan Sonyeondan [방탄소년단]) as the top artist in the Artists 100 List. These seven South Korean musicians are everywhere and celebrated as not only the most successful K-Pop band of all time, but also the first to crossover to dominate the US and UK charts. They are the first K-Pop band to perform at the Grammys. They won multiple awards at the 2018 and 2019 American Music Awards and Billboard Music Awards. They are young Asian men that have become idols not just in Korea, but worldwide, including the US. BTS was in Time Magazine’s list of the most influential people of 2019. Korea estimates that in 2017, about 8% of foreign tourists to Korea visited because of BTS, and their value to the Korean economy was about $3.5 billion dollars that year. It has certainly increased from then. BTS has been on the Billboard 100 Charts continuously for 181 weeks as we write this. They have had four Number 1 Albums on Billboard 100 in 2 years – the last group who accomplished this feat faster was The Beatles. According to a March 10, 2020 Forbes Magazine article, BTS claimed all ten spots of the Top 10 World Digital Song Sales. Given that BTS has mostly released songs in Korean (recently mixed with some English), it is remarkable that their songs reverberate to non-Korean speaking audiences. Their devoted fans are known as the ARMY, and they hail from all over the world and span all ages.

Along with their unparalleled success in the global popular music market, the influence of BTS is even visible in our everyday lives. For example, when reporting a problem with his apartment in Columbus, Ohio, Wonseok had to give his name to an African American woman in her 30s working at the help desk. Her immediate response was, “You must be from Korea…I’m an ARMY (member). I’m familiar with Korean-style names because I’m a huge fan of Jungkook of BTS.” (Most ARMY members have a favorite member, or a bias). Wonseok has a white friend in her 20s in Toledo, Ohio, who recently told him that she and her mother compete for who writes most often about BTS on their social media accounts.

The omnipresence of BTS, along with the growing popularity of Korean dramas in the US (via Netflix), the Academy Awards for Bong Joon-Ho’s Parasite, and the groundbreaking films Crazy Rich Asians, Always Be My Maybe, and The Farewell, which all featured Asian American filmmakers and actors, signaled a possible turning point in how Asian Americans might be viewed by non-Asian Americans. There were, until recently, even two Asian American candidates for president (Kamala Harris and Andrew Yang). Despite the celebration of Asian Americans as “model minorities,” many of us believe that our status as Americans has always been provisional. The recent turn of new media images presents Asians and Asian Americans as clean-cut, attractive, innovative, and most importantly, like any other American.

Now we are faced with the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition to its threat to the physical health of billions of people worldwide and hundreds of millions of individuals in the United States, individuals of Asian descent face an additional burden by virtue of their racial identity. Some conservative politicians have begun calling Coronavirus the “Wuhan Virus” or the “Chinese Virus.” In his March 11, 2020 address, President Trump called COVID-19 the “foreign virus.” In a later speech, he also referred to COVID-19 as the “Chinese Virus.” Media outlets regularly use photos of Asians wearing face masks to accompany any article about coronavirus anywhere in the world (even outside Asia). While the countries that have the most cases have expanded well beyond Asia (with the US overtaking other countries as we write this), in the US, Asian Americans have become the embodiment of the illness. Even as COVID-19 has struck Italy, Spain, and the United States, it is individuals of Asian descent and businesses run by Asians and Asian Americans that are being avoided. In contrast, the sudden increase of the incidence of Coronavirus in Italy, Spain, and France will likely not prompt Americans to avoid businesses run by them or individuals from these countries.

In the short time since the outbreak of COVID-19, hate crimes and microaggressions against Asian Americans have been on the rise. On March 8, 2020, a Chinese American man in Brooklyn was stabbed 13 times in his neck, and he is fighting for his life. New York Daily News reported on March 11, 2020 that a 59 year-old Asian man walking in New York City’s Upper East Side was kicked in the back by a teenager who yelled, “F—king Chinese Coronavirus” and then was told to go back to his country. On the same day, another 23-year old Asian American woman reported that a stranger yelled “Where’s your coronavirus mask, you Asian b—h.” Three members of an Asian American family (including a 2- and 6-year-old) were stabbed at a Sam’s Club in Midland Texas on March 17, 2020. The suspect said that he thought they were carrying the coronavirus. JRG Electric, an electrical contracting company in Omaha, Nebraska displayed a sign that stated, “Closed due to slanty eyed c*nts.” As of late March, the FBI had issued a warning of a potential surge in hate crimes against Asian Americans.

On Twitter as well as via mainstream media outlets, there continues to be countless reports of Asians being yelled at or attacked by strangers. We have also seen and witnessed microagressions firsthand. By early March 2020, a Korean owner of a nail salon told Grace that business is down because “everyone wants to avoid Asians.” At Union Station in New Haven, Grace witnessed an Asian American man sneeze. A non-Asian American elderly woman near him backed up so quickly in response that she hit the back wall of the establishment. All over social media, our friends and acquaintances have reported exaggerated negative responses not just to a cough or a sneeze by Asian Americans, but simply to their physical presence. Mark Hayward, a sociology professor at the University of Texas, Austin reported that his PhD student (who is of Korean descent) had his Airbnb canceled because he was Korean. He tried to convince the owner that he was not dangerous since he had not been to Korea in over a year.

In fact, Asian Americans have suffered from the association between us and disease since our arrival to this country in the 1800s. The first acts to restrict immigration based on national-origin were The Page Act of 1875 and The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. Asian Americans were seen as dirty, diseased, and compared to vermin. While other immigrant groups faced these stereotypes, it seems to have persisted with us longer than for others. Chinese Americans were blamed for an outbreak of the Bubonic Plague in San Francisco in the early 1900s. Our status as foreigners was reinforced when Japanese American citizens were interned during WWII. We are constantly reminded that we are not really Americans with the everyday questioning of “where are you from” and the commentary that “you speak English so well” no matter whether we are new arrivals or if our grandparents were born in the US.

As scholars in Sociology, Asian American Studies, and Ethnomusicology, we watched in awe when the members of BTS (RM, J-Hope, Suga, Jimin, V, Jin, and Jungkook) performed “Boy with Luv” on Saturday Night Live (being the first Asian band to ever perform on SNL). A few weeks ago, they sang and danced to their newest single “ON” in Grand Central Terminal for The Tonight Show. Just two nights ago (March 30, 2020), BTS appeared on James Corden’s Homefest Show (as a substitute for The Late Late Show, which was on hiatus due to COVID-19) along with Billie Eilish, John Legend, Dua Lipa, and even Andrea Bocelli. Each of these well-known musicians performed from their homes. We wondered still if BTS could help to reinvent the image of Asians and Asian Americans to Americans not of Asian descent (or even to Asian Americans themselves). Certainly, they are clean, healthy, and attractive. They have legions of non-Korean and non-Asian fans. Doesn’t this mean that other Asian Americans can also be imagined as clean, healthy, and attractive? Could the omnipresence of BTS help reduce xenophobia against Asians and Asian Americans? The answer, after this past month, is probably not (yet). Still, their visibility in American pop culture could not possibly hurt the image of Asians and Asian Americans in the US and beyond.

Grace Kao is IBM Professor and Chair of the Sociology Department at Yale University. Previously, she served as Director of Asian American Studies at the University of Pennsylvania. Along with Kara Joyner and Kelly Stamper Balistreri, she recently published a book titled The Company We Keep: Interracial Friendships and Romantic Relationships from Adolescence to Adulthood. Among the BTS members, her bias is J-Hope.

Wonseok Lee is a PhD student in Ethnomusicology at Ohio State University. His research focuses on Korean popular music, globalization, transnationalism, and identity. He was formerly a session musician in Korea for many K-Pop Acts such as Lee Hyo-ri, Shinwha, Sg Wannabe, and BuskerBusker. Among the BTS members, his bias is V.

Comments 15

Damian Carpenter

April 2, 2020COVID 19 is the big challenge for the people who are suffering from this disease and i saw lots of people are hating them and avoid to help them, in fact, they need more attention so please visit https://www.travelclinicny.com/ for the best treatment and information thanks

nhparkdental

April 10, 2020The whole world is fighting against the COVID 19. The most contagious disease that has ever been experienced in history. More than 96K have died already.

wisliam

April 16, 2020Thanks

Johnsmtied

April 16, 2020I totally agree with all the facts that are been discussed in this article about the effects of corona virus. Also you need to visit https://www.bestessays.com/ to complete quality work. It not only damages human lives but also destroyed the biggest economies of the world. Even i America more than 3 million peoples are unemployed.

Catherine Johnson

April 21, 2020Indeed it is a widely discussed topic now but if you want to read a very constructive discussion regarding COVID-19 impact then https://www.lakenormanhardscapes.com/ is the best place to visit as I recently visited that discussion.It actually changed my mind literally.

Anna

April 30, 2020Different countries around the world have been defensing this pandemic COVOD-19 and most of the Doctors say to get washed hand and wear face mask properly. I work at the bestfreesexgames.co.uk by which other people could get involved with developing their process of support.

Anna

April 30, 2020Different countries around the world have been defensing this pandemic COVOD-19 and most of the Doctors say to get washed hand and wear face mask properly. I work at this site https://www.bestfreesexgames.co.uk by which other people could get involved with developing their process of support.

pikachu chu

May 5, 2020covid-19 is caused by the corona virus which causes symptoms of coughing, tightness in the chest, and breathing. atari breakout

Leo

May 12, 2020It's a very critical condition in the whole world to stay home and stay safe..

must try : https://couponado.com/

Robert

May 15, 2020Since extensive social distancing is not being practiced in most of the countries, the time-to-peak for the pandemic is still uncertain.

Symons

June 2, 2020Being green or eco-friendly is coming to be a growing number of important. ... Eco-friendly products promote environment-friendly living that help to save power as well as also prevent air, water as well as sound pollution. They show to be advantage for the atmosphere as well as likewise protect against human health from wear and tear.

eco friendly products

axen

June 6, 2020Covid has been impacting a lot of lives... The things which should harm environment shouldn't be used so that these kind of viruses doesn't come.

Find more information about solar grave lights and cemetery lights for decoration can be found at https://greenmetropolis.com/solar-cemetery-lights/

axen

June 6, 2020Covid has been impacting a lot of lives... The things which should harm environment shouldn't be used so that these kind of viruses doesn't come.

Find more information about solar grave lights and cemetery lights for decoration can be found Solar lights for graves and cemetery

Paul

June 18, 2020The situation is really critical due to COVID 19. When it comes to academics, students like me are facing serious issues regarding completing their assignments. But Thanks to the CheapestEssay.com that they really provided me great support in this pandemic situation too.

New England Patriots Game

June 25, 2020The National Football League is a professional American football league consisting of 32 teams, divided equally between the National Football Conference and the American Football Conference.