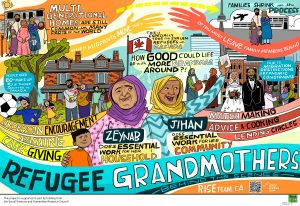

ThinkLink Graphics // Delaney Cox

The Case for Grandmothers

It was a bracingly cold morning in 2019 in a far suburb of Toronto, Canada. I stepped across the threshold of Amina’s bungalow, taking her hand and leaning in to kiss the air beside each of her cheeks. In my other hand, I clutched a box of sweets I’d brought for her elderly mother, a token of appreciation for welcoming me into their home.

Amina, a mother of five, was a participant in my multi-year study following the successes and challenges of 148 Syrian mothers and teenagers admitted to Canada under the Syrian Refugee Resettlement Initiative (SRRI). On that chilly November morning, I found Amina’s elderly mother, Zeynab, playfully wrangling her youngest grandchild, a rambunctious toddler, on one of the thin mattresses (doshak) that lined the home. From behind a drywalled addition, Zeynab’s own mother, Rashida, called out for assistance getting up from bed. A few minutes later, having gathered all four generations of her family together on the doshak, Zeynab opened the box of sweets, inhaled deeply, and offered the first chocolate to me.

Multigenerational households like Amina’s are rare in Canada, even among migrant populations. The country’s immigration system makes it particularly challenging for migrant families to establish multigenerational households, even when they desire to do so, as it favors younger “economic” migrants while making it difficult for them to bring their elderly relatives along. In fact, since 2015, fewer than 5% of those admitted to Canada under the SRRI have been above the age of 60. Compared to the United States, Canada has a weaker family reunification program and employs a more restrictive definition of “family” (defined only as parents, spouses, or children under 18 years old). Beyond these policy constraints, many migrant families encounter financial obstacles that prevent them from bringing their elderly family members to Canada.

Nearly all the families in the study were forced to leave behind multiple members of their households when they relocated to Canada. And according to study participants, the most critical missing persons were elder matriarchs like Zeynab and Rashida, whom they described as invaluable sources of power, support, and wisdom. Only two of the 53 households in the study had successfully resettled their elder matriarchs in Canada.

As my collaborators and I described in a recent article, “Grandmothers Behind the Scenes,” studying these two households offered a unique window into what life could be like if immigration policies better supported the preservation of multigenerational households.

The experiences of Zeynab and another grandmother named Jihan illuminated both the challenges and possibilities associated with multigenerational migrant households in this context. One of the key challenges we identified stemmed from the broader devaluation of older adults in Canadian society, which was intensified by their exclusion from immigration services like career and employment programs. These conditions led to a loss of authority and social status—a stark contrast to the respected positions these women held back in Syria.

Still, the resettled grandmothers demonstrated remarkable resilience, reclaiming their roles as valued members of their families and within the broader migrant community. Through various creative, life-affirming pursuits, they provided essential care and support within and beyond their households.Zeynab found tremendous purpose through work within her household, where she cared for her grandchildren, great-grandchildren, and her own elderly mother. This caregiving labor enabled her daughter Amina to take English classes and work for pay outside the home, strengthening the family’s foothold in Canadian society. Zeynab took pride in teaching the youngest children their family’s language, culture, and religious traditions. And after Amina experienced mistreatment from her husband in the months following their resettlement, Zeynab provided constant emotional support that ultimately empowered Amina to separate from him.

At first glance, it may seem that Zeynab was giving much and receiving little. Yet, there was a balanced reciprocity in these relationships. Zeynab, a cancer survivor, credited her survival to her “second mother,” her daughter Amina.

Jihan, the other grandmother in our case study, forged her sense of purpose in her broader community, aiding the resettlement processes of those outside her household. For example, having previously paired over a hundred couples back home, she reestablished her matchmaking services in Toronto (in her efforts to help the Syrian Canadian diaspora grow, she also tried several times to recruit members of our research team into her pool of eligible Toronto singles!). Jihan created a local lending circle for Syrian women entrepreneurs who lacked access to capital investment. And for the many newcomers forced to leave their elders behind, Jihan became a source of wisdom on every topic, from cooking to marriage to finances.Despite scarce material resources, both Zeynab and Jihan provided essential forms of care that improved others’ lives, both materially and socially. Yet Canada’s commitment to reunifying elders with their families remains weak. The current immigration system tends to portray elders like Zeynab and Jihan through a deficit lens, construing them as social burdens rather than assets. This perspective fails to acknowledge the countless forms of valuable care and support that older adults provide to their families and society. By highlighting the contributions of Zeynab and Jihan, our research underscores the importance of multigenerational caregiving in promoting the well-being of individuals, families, and communities.

Neda Maghbouleh is in the Department of Sociology at the University of British Columbia. She is the author of The Limits of Whiteness: Iranian Americans and the Everyday Politics of Race.

Comments