Image by Alexandra_Koch on Pixabay

Healthcare and Critical Infrastructure

As of 12 noon on March 29, 2020 EST, there are 685,623 diagnosed coronavirus cases worldwide. The United States has 125,313 diagnosed cases. Italy’s death rate is 10.8% as the country approaches 100,000 diagnosed cases. The spread of the virus seems to have slowed in China after a full lockdown, while the U.S. is experiencing one of the steepest increases by country.

Some countries and territories have managed to contain the virus better than others. Taiwan has few cases (about 300), despite its proximity to Wuhan, China. But, the coronavirus outbreak has exposed what the Global Health Security Index found—the world is not prepared for an outbreak. Scores were abysmal for the 195 countries. Though the United States received the highest overall score (83.5), some indicators were concerning. For example, the United States scored only 66.7 on emergency response operations (still ranking second among all countries). Health capacity was scored 60, while healthcare access was scored 25 (ranked 175). These outcomes speak to the inequalities embedded within the United States.

Scientists suggest that what countries learned from previous outbreaks and how they implemented changes is vital to future preparedness. In the United States, the Obama administration learned from pH1N1 in 2009 that killed over 12,000 Americans. When the Ebola virus outbreak occurred in 2014, the Directorate for Global Health and Security and Biodefense was created. Though Ebola killed over 11,000 worldwide in 2014, less than 10 people who had the virus arrived in the U.S. and only two people died. The Trump administration disbanded this unit, stating that they simply reorganized. When Congo had an Ebola outbreak in 2018, the Trump administration claimed their reorganization proved formidable. However, it seems that some African countries learned from the 2014 Ebola outbreak and were better prepared in 2018. Congo ranked 11th on exercising response plans according to the Global Health Security Index. Ranking 54th on this indicator, the following was reported about the United States: “There is no evidence that the U.S. has undergone an exercise to identify a list of gaps and best practices.”

The articles in this wave of our COVID-19 special issue illuminate the importance of having a formidable healthcare infrastructure that interweaves federal, state, and local governments. They also highlight the benefits of universal and equitable healthcare systems. Factors including efficient testing, accurate reporting, communication, trust, social capital, and community preparedness impact what is occuring at state health offices, hospitals, community clinics, and local neighborhoods.

As these articles show, the factors noted above are not only important to contain coronavirus and reduce the outbreak, but they are essential for giving healthcare providers the confidence to provide medical care for those who contract the virus. Healthcare providers must feel empowered and secure in their roles in order to save lives. When a country, like the United States, does not have enough personal protective equipment (PPE) and instead has providers wearing trash bags and bandanas, it harms the most vulnerable and marginalized among us and endangers the lives of those sworn to help them heal. In 2014, healthcare workers represented 10% of people who died from Ebola. It is vital for countries to learn from the past in order to save lives in the present.

– Rashawn Ray and Fabio Rojas

- ”The False Narrative of Safety for Small and Mid-size Cities amid the COVID-19 Pandemic” by Marquinta L. Harvey, Angela S. Bowman, and Denise Bates-Fredi

- ”Social Capital, Trust, and State Coronavirus Testing” by Cary Wu, Rima Wilkes, Malcolm Fairbrother, and Giuseppe Giordano

- ”Working in the Emergency Department During a Virus Outbreak: Lessons from the Ebola Crisis” by April L. Wright, Alan D. Meyer, Trish Reay, and Jonathan Staggs

- “COVID-19 Response May Depend on Strength of State’s Medicaid Program” by Josh Pacewicz

- “Diversity in Response: How State Governments Disseminate Information about Coronavirus” by Kevin Hans Waitkuweit

- ”Rural Healthcare and the Coronavirus Pandemic” by Derrick Shapley

- ”Immigrant Health and COVID-19 in the United States” by Meredith Van Natta

- ”The Resiliency of Community Pandemic Preparedness” by Ry Brennan and the Members of Bonfire Collective

- ”Viruses Don’t Care about Borders” by Joseph Harris

“The False Narrative of Safety for Small and Mid-size Cities amid the COVID-19 Pandemic” by Marquinta L. Harvey, Angela S. Bowman, and Denise Bates-Fredi

We are receiving daily reports on the rising number of cases of COVID-19 here in the United States and around the world. At a time when quick decisive action can be a matter of life and death, a simple misunderstanding between raw counts and prevalence rates has created a feeling of false security in small and mid-sized communities.

During the March 19, 2020 White Housing briefing on COVID-19 Dr. Birx said:

“I know many of you are looking at the state-level data. Still, over 50 percent of the cases come from three states. This is why we continue to prioritize testing in those states. In addition, 50 percent of the cases come from 10 counties. We are a very large country with very many counties.”

This information has the potential to create a dangerous narrative and dire consequences for small to mid-size cities and rural areas. Residents of these areas may feel that they are less susceptible and at lower risk than they really are; thereby, not practicing the prevention necessary to keep their families safe.

When examining how fast a disease is transmitting from one person to the next in a specific area we often rely on raw counts, and this is the information that we are receiving daily from our local and state health departments and various media outlets. The information on daily counts is vital to our fight against the spread of this disease however, raw counts alone will not allow us to see the full scope of the problem in different geographic locations. We must dispel the myth that fewer cases equate to a lesser problem or increased safety.

A count is the number of cases that can be described in terms of person, place, and time, while rate is a measure of frequency with which an event occurs in a defined population over a specified time period (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2012). We cannot use raw counts to determine if the problem is more concentrated in one area than in another geographic location. Sharing location specific information that includes rates could prove beneficial for individuals with decision-making power by putting the occurrence of COVID-19 cases in perspective for the local population at risk. This allows for more useful comparisons when leaders are investigating the magnitude of the problem in their communities.

U.S. state counties with the same number of cases can be remarkably different when assessing the magnitude of the problem. For example, Hillsborough County, Florida and Los Angeles County, California have dramatically different case counts 42 and 292, respectively. The common assumption is the problem is larger in Los Angeles County, California, however this is not the case when population at risk is factored into the assessment. According to 2010 US Census data, Hillsborough County, Florida has a population of 1.2 million and Los Angeles County, California has a population of 9.8 million. When calculating the prevalence rate for COVID-19 the two aforementioned counties have the same prevalence rate of 3 cases per 100,000 persons, illustrating the same level of risk. If these counties are only using raw counts, then they may have varying approaches in their containment efforts that may range from helpful to harmful. However, if prevalence rates are calculated it may encourage areas with similar prevalence, whether large or small, to implement similar containment approaches. The opposite can also be true, where counties have similar case counts but different prevalence rates. For example, Summit County, Utah has a case count of 37 and Kershaw County, South Carolina has a case count of 36 but their prevalence rate varies greatly 102 cases per 100,000 persons and 58 cases per 100,000 persons, respectively (please see Table 1 for more comparisons).

The importance of including prevalence rates into the COVID-19 conversation is vital in moving appropriate precautionary measures forward. Information in the correct context is needed to relay the importance of making the necessary decisions that impact the lives of our neighbors. Small to mid-size communities need to use caution when using raw counts for decision making and assess the magnitude of their risk by examining prevalence rates when using geographic comparisons.

| Table 1 | |||

| Example of the Impact of Population Size on Prevalence Rate of COVID-19 | |||

| County and State | COVID-19 Cases | 2010 Census Population | Prevalence Per 100k |

| Summit County, UT | 37 | 36,324 | 102 |

| Orleans Parish, LA | 352 | 343,829 | 102 |

| Kershaw County, SC | 36 | 61,697 | 58 |

| Nassau County, NY | 754 | 1,339,532 | 56 |

| Bartow County, GA | 56 | 100,157 | 56 |

| Williamson County, TN | 47 | 183,182 | 26 |

| Morton County, ND | 7 | 27,471 | 25 |

| Davidson County, TN | 140 | 626,681 | 22 |

| Burleigh County, ND | 15 | 81,308 | 18 |

| Cook County, IL | 548 | 5,149,675 | 11 |

| Lake County, IL | 63 | 703,462 | 9 |

| Los Angeles County, CA | 292 | 9,818,605 | 3 |

| Hillsborough County, FL | 42 | 1,229,226 | 3 |

References

Center of Disease Control and Prevention. (2012). Division of Scientific Education and Professional Development. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/csels/dsepd/ss1978/lesson3/section2.html

County of Los Angeles Public Health. (2020). Novel Coronavirus in Los Angeles County. Retrieved from http://publichealth.lacounty.gov/

Florida Department of Health. (2020). Florida’s COVID-19 Data and Surveillance Dashboard. Retrieved from https://experience.arcgis.com/experience/96dd742462124fa0b38ddedb9b25e429

Georgia Department of Health. (2020). Georgia Department of Public Health COVID-19 Daily Status Report. Retrieved from https://dph.georgia.gov/covid-19-daily-status-report

Illinois Department of Health. (2020). Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Retrieved from https://www.dph.illinois.gov/topics-services/diseases-and-conditions/diseases-a-z-list/coronavirus

Louisiana Department of Health. (2020). Coronavirus (COVID-19). Retrieved from http://ldh.la.gov/coronavirus/

Nassau County Department of Health. (2020). Coronavirus. Retrieved from https://www.nassaucountyny.gov/DocumentCenter/View/28877/POSITIVES-BY-PLACE—3-20-pm-Revised

North Dakota Department of Health. (2020). North Dakota Coronavirus Cases. Retrieved from https://www.health.nd.gov/diseases-conditions/coronavirus/north-dakota-coronavirus-cases

New Jersey Department of Health. (2020). New Jersey COVID-19 Dashboard. Retrieved from https://www.nj.gov/health/cd/topics/covid2019_dashboard.shtml

Tennessee Department of Health. (2020). Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19). Retrieved from https://www.tn.gov/health/cedep/ncov.html

Utah Department of Health. (2020). Overview of COVID-19 Surveillance. Retrieved fromhttps://coronavirus.utah.gov/case-counts/

Marquinta L. Harvey is an Epidemiologist with the Tennessee Department of Health Office of Informatics and Analytics. Her research interests include stress-related psychopathology, mental health, workplace wellness, and social determinants of health.

Dr. Angela Bowman is an Assistant Professor in the Health and Human Performance Department at Middle Tennessee State University. Her academic and consulting background spans local and national non-profit organizations that seek to reduce the burden of chronic and rare diseases through assessment of physical and social determinants of health and well-being.

Denise Bates-Fredi is Associate Professor and Assistant Director of the Masters of Public Health Program at Louisiana State University-Shreveport and Louisiana State University Health Science Center-Shreveport. Her research and programmatic focus is generalized to health disparities in under-served people groups in global communities.

“Social Capital, Trust, and State Coronavirus Testing” by Cary Wu, Rima Wilkes, Malcolm Fairbrother, and Giuseppe Giordano

We have been here before. The Bubonic Plague. Smallpox. The Spanish Flu. Ebola. MERS. SARS. And now COVID-19. These outbreaks aren’t simply health problems. They spread because of our inherently social nature. Trade routes. Travel. All our global connectedness. This means that COVID-19, which strikes through social networks, is even more of a social problem than other diseases. It definitely requires a social solution. The global pandemic that started in Asia has spread to Europe and is currently taking hold across North America.

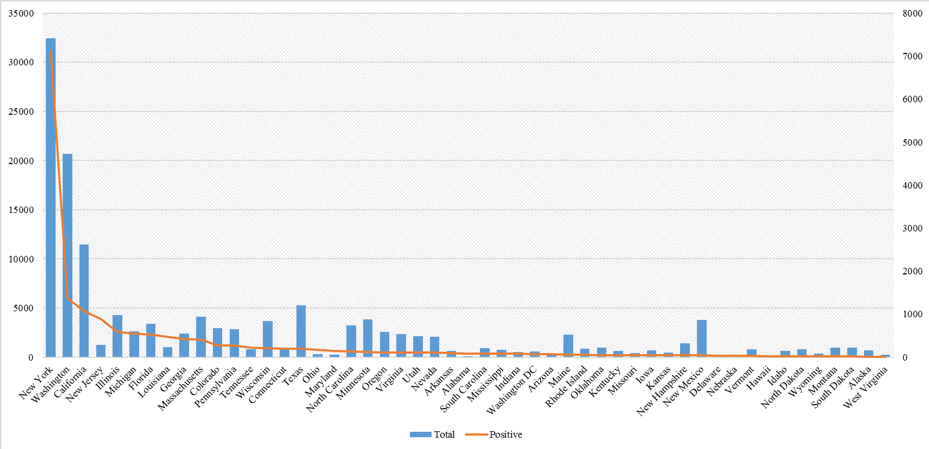

Since January, when the first case was reported in the US, the number of confirmed cases and deaths has been growing exponentially. On March 26, the US overtook China to become the country with the largest number of confirmed coronavirus cases (n=82,404). The actual number of Americans that have COVID-19 is still unknown. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have stopped publishing testing data. Some of the most comprehensive data are, however, available from The COVID Tracking Project. This project provides state and district-level information (updated daily) on positive and negative test results, on pending tests, on number of deaths, and on the total number of individuals tested. Using these data, Figure 1 shows the differences in the total number of individuals that have been tested across US states (left axis) and the number of positive cases (right axis).

While these numbers provide a helpful preliminary picture, we cannot, simply based on these numbers, tell how widespread the coronavirus is for each state. The numbers are incomplete, since not all states have been able to regularly report full sets of numbers on an ongoing basis. Further is that we will also need to take into account the fact that population varies significantly in size across states.

However, we can tell what is happening at the local level by ranking all states from high to low according to the number of positive cases reported together with the total individuals tested, as shown in Figure 1. The number of positive cases reported does not correlate very well with the total number of individuals being tested. For example, New Jersey is ranked fourth in terms of the number of positive cases, yet its total testing number is lower than many other states. In contrast, New Mexico has a much higher number of total cases being tested, but its number of positive cases is ranked towards the bottom.

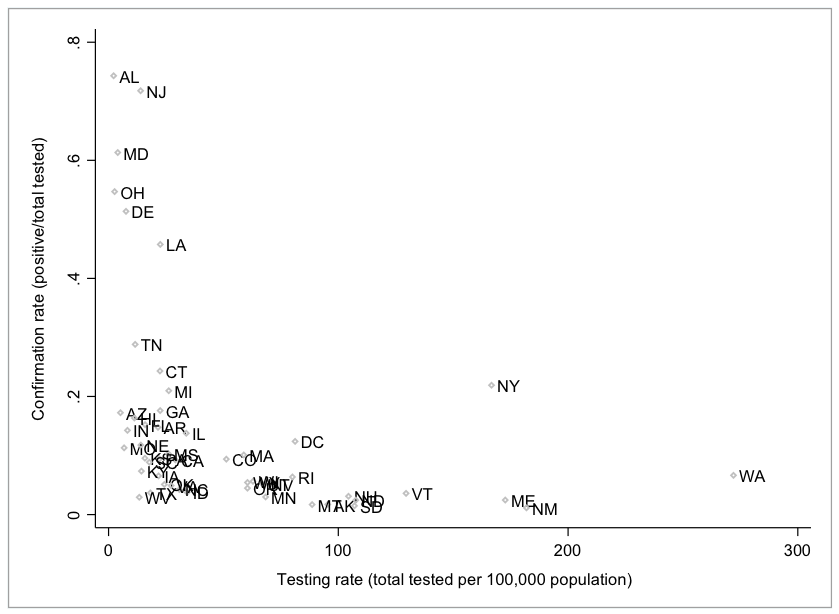

It is apparent that some states might have performed better than others in getting people tested. To better illustrate this point, we calculated the testing rate (per 100,000 population) across states by comparing the total number of individuals tested relative to the state population (obtained from the US Census Bureau). We can also calculate the per tested confirmation rate for each state by dividing the total number of positive results by the total number of individuals who have been tested. Whereas the confirmation rate might provide some indication of the prevalence of the coronavirus in each state, the testing rate shows how quickly each state government has swept into action.

Note: Testing data from The COVID Tracking Project. Population data from Census.gov. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

Figure 2 provides a scatterplot showing the relationship between these two numbers. It shows that some states such as Washington (WA), New York (NY), Maine (ME), South Dakota (SD), New Mexico (NM), New Hampshire (NH), and Vermont (VT) are able to test many more people per capita than others, even though they have lower confirmation rates. In contrast, other states such as Maryland (MD), Alabama (AL), New Jersey (NJ), Ohio (OH), Delaware (DE), Louisiana (LA), and Tennessee (TN) have higher confirmation rates, but have lower testing rates.

Testing is critical to stopping the outbreak. Untested patients were the majority of those who transmitted the coronavirus in China (Li et al. 2020). In the U.S., Trump’s obfuscations and the delay in getting people tested explain the rapid spread of the coronavirus through American communities (Yong 2020).

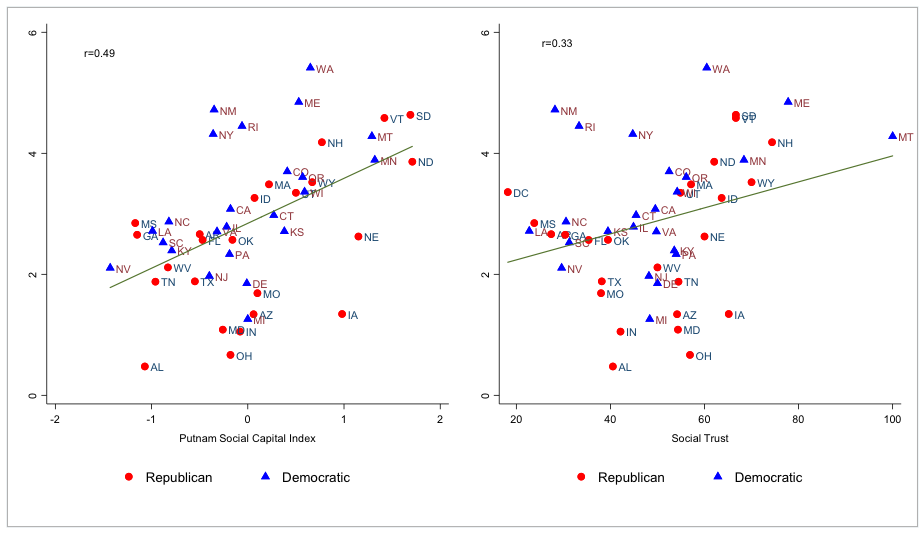

At the state level, some states have been able to respond more quickly and more effectively than others. What can explain differences in the testing rate across states? Why might some states perform better than others in response to the on-going COVID-19 crisis? We believe that social capital and trust may be playing an important role.

In Making Democracy Work, Robert Putnam and his coauthors (1993) argued that local government performs better when there are higher levels of generalised trust and strong civic norms. Social capital and trust increase political sophistication and promote spontaneous cooperation within society. States with higher trust and social capital are in a better position to be able to mobilize resources and foster collective actions. In fact, the linkage between social capital, trust, and the quality of government at the state-level has been widely demonstrated empirically (e.g., Knack 1999).

So can social capital and trust explain the quality of response in the face of COVID-19 across US states? In Figure 3, we provide a scatterplot of the relationship between state-level social capital, trust and the COVID-19 testing rates (log10 scale). We use the log transformation of the testing rate so as to better indicate the testing rate across US states in a relative sense (e.g., ranking order). Otherwise, the results will be heavily influenced by states, such as New York and Washington, which have very high absolute numbers of total testing cases, or by states such as Alaska and Hawaii that have very low absolute numbers of total testing cases.

The results clearly show that both social capital and social trust levels positively predict the quality of response to COVID-19 outbreak. States that have higher levels of social capital tend to have higher testing rates (r=0.49) and states with more trust also have higher testing rates (r=0.33). The pattern holds, irrespective of Republican or Democratic state governance. Additional tests (not shown) find that this effect also holds when we control for state-level median household income, income inequality (GINI index), and/or racial diversity.

Social capital and trust may be especially important in democratic societies, as compliance cannot be ensured by more forceful means. People with little confidence in their government and/or health agencies are less likely to comply with prevention and control measures. During times of crisis, citizens also need to trust each other. That way they can respond collectively. The states that are now leading in COVID-19 testing are also going to be in a better position to respond to it.

COVID-19 is almost exclusively spread through human to human contact. This means that an understanding of public responses and social relations in times of crisis is essential to stopping the spread of this disease. We are members of one of several research teams that received a rapid response grant on the outbreak fromCanadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). To contribute to global efforts to contain the COVID-19outbreak, we have brought together frontline researchers from China, including at the center of the outbreak- Wuhan city, as well as trust and public health scholars in Canada and Sweden to study the dynamics of trust and social capital in this global pandemic.

References

Knack, Stephen. 1999. “Social capital and the quality of government: Evidence from the United States.” American Journal of Political Science 46:772-785.

Putnam, Robert D., Robert Leonardi, and Raffaella Y. Nanetti. 1993. Making democracy work: Civic traditions in modern Italy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Putnam, Robert D. 2000. Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Rothstein, Bo. 2011. The quality of government: Corruption, social trust, and inequality in international perspective. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Li, Ruiyun, Sen Pei, Bin Chen, Yimeng Song, Tao Zhang, Wan Yang, and Jeffrey Shaman. 2020. “Substantial undocumented infection facilitates the rapid dissemination of novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV2).” Science.10.1126/science. abb3221

The COVID Tracking Project. 2020. Coronavirus numbers by state. Source link: https://covidtracking.com/. Accessed on March 26, 2020.

The Social Capital Project. 2020. The geography of social capital in America. Source link:https://www.jec.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/republicans/socialcapitalproject. Accessed on March 26, 2020.

Wu, Cary et al. 2020. “The Dynamics of Trust Before, During and After the COVID-19 Outbreak.” Canadian Institutes of Health Research. (Cary Wu, PI). Rapid Response Grant: https://www.canada.ca/en/institutes-health-research/news/2020/03/government-of-canada-funds-49-additional-covid-19-research-projects-details-of-the-funded-projects.html. Accessed on March 26, 2020

Yong, Ed. 2020. How the Pandemic Will End. The Atlantic. March 27.

Cary Wu is an Assistant Professor of Sociology at York University. Their research focuses on political culture, migration and cities.

Rima Wilkes is a Professor of Sociology at the University of British Columbia. Their research investigates how politics is related to racial and ethnic inequality.

Malcolm Fairbrother is a Professor of Sociology at Umeå University where they research the politics of environmental protection, economic globalization, and social dis/trust.

Giuseppe Giordano is an Associate Professor of Genetic and Molecular Epidemiology at Lund University.

“Working in the Emergency Department During a Virus Outbreak: Lessons from the Ebola Crisis” by April L. Wright, Alan D. Meyer, Trish Reay, and Jonathan Staggs

As the COVID-19 pandemic stretches public health systems around the world, the role of hospital emergency departments has never been more important. Whether people are acutely ill with symptoms from coronavirus or from other illnesses and injuries – such as heart attacks, strokes, or trauma accidents – citizens expect that the emergency department will be open and offer care. In this way, emergency departments function both as a place of medicine and as an institution that society has entrusted to accomplish normative values of ensuring citizens have access to essential services. Emergency doctors and nurses can be conceptualized as institutional custodians because they are the caretakers whose job it is to preserve this institution of healthcare. They help protect the human welfare, order, and stability of society through their everyday work in local emergency departments. As the coronavirus pandemic accelerates, the work of these institutional custodians becomes increasingly difficult as demand threatens to outstrip health system resources, and as more patients pose infection risks to frontline responders. How can institutional custodians in emergency departments stay the course during the coronavirus pandemic?

An empirical study of an emergency department during the Ebola outbreak offers some insights. The study by Wright, Meyer, Reay and Staggs, forthcoming in Administrative Science Quarterly, is based on an ethnography at a public hospital emergency department in Australia. While data were being collected, the World Health Organisation (WHO) declared a public health emergency of international concern in August 2014 following an outbreak of Ebola in West Africa. WHO estimated a possible 20,000 cases of Ebola and a mortality rate of 70 per cent, with 10 per cent of these projected to be healthcare workers. The first cases of Ebola transmission outside of Africa occurred in October 2014, when nurses in Spain and the USA tested positive for Ebola after treating international travellers. The media fed worldwide hysteria that “Ebola is coming to kill us all.” People were afraid, especially the doctors and nurses in emergency departments tasked with providing Australia’s frontline response to Ebola.

The Ebola outbreak gave the authors a unique opportunity to observe the work of institutional custodians in an emergency department in normal times and during the extraordinary circumstances of a potential pandemic. The study shows that the interplay of risk perceptions and fear affected how doctors and nurses initially responded to Ebola. Fear was aroused by perceptions of unknown risk. Ebola’s disease process was unfamiliar and procedures to prevent transmission of infection were unproven. Doctors and nurses worried that their own lives and families could be threatened by treating an infected patient. The immediate response to this fear was a desire to withdraw from their usual role as institutional custodians and take extraordinary actions to avoid harm by closing off access to the emergency department – to somehow prevent people who might have contracted the Ebola virus from presenting to the institution in Australian society where guaranteed access to medical care is paramount.

The analysis revealed two factors that helped doctors and nurses to bring their fear as institutional custodians under control. First, doctors and nurses received more robust information sources over time and were provided better resources and training to prepare the frontline Ebola response. Second, as doctors and nurses contemplated excluding patients from the emergency department, their commitment as custodians to the normative values of the institution triggered what psychologists call moral emotions. They felt a prosocial desire to do the “right thing” to ensure that every person who turned up at the emergency department received appropriate care, no matter what their potential illness. These moral emotions – which are more reflective and self-conscious than basic emotions – dampened the fear. Together, these two factors enabled doctors and nurses to re-evaluate risk. Instead of seeing Ebola as an unknown risk and fearfully taking actions to avoid it, doctors and nurses shifted to perceiving Ebola as a normal risk. Accordingly, they developed and implemented locally-contextualised actions to mitigate harm. They treated a number of people suspected of being infected with the Ebola virus (there were no confirmed cases in Australia) and maintained their work as institutional custodians.

To date, institutional custodians have managed to stay the course in the face of the coronavirus pandemic. The findings of our study of Ebola help to explain their perseverance. In contrast to their response to the Ebola outbreak as an unknown risk, custodians in emergency departments have responded to COVID-19 as a normal risk. Although the virus is unfamiliar and easily transmitted, the mortality rate is low and standard procedures for common infectious diseases – especially personal protective equipment – appear to be effective in mitigating harm. Fear of personal harm is likely to be manageable. Moral emotions motivate custodians in emergency departments to work in ways that mitigate, rather than avoid, harm. These actions will preserve the normative values of the institution, keeping local emergency departments open to provide access to emergency medical care for all citizens in need, whether coronavirus-related or not. However, as the pandemic spreads, the resources needed for personal risk mitigation are becoming scarce in some emergency departments due to supply chain disruptions and/or patient overload. As this occurs, custodians’ fears may overwhelm moral emotions to the point that some local emergency departments become unable to fulfil their function as societal institutions. A key implication of the Ebola study for the COVID-19 pandemic is that while it is imperative to “flatten the curve” through social distancing and travel restrictions, it is equally important for governments to build capacity by ensuring institutional custodians at the frontline have the resources they need to maintain moral emotions and manage fear.

References

Wright, A.L., Meyer, A.D., Reay, T. and Staggs, J. (2020) “Maintaining Places of Social Inclusion: Ebola and the Emergency Department”, Administrative Science Quarterly, DOI 10.1177/0001839220916401.

Haidt, J. (2003)“The moral emotions.” In R. J. Davidson, K. R. Sherer, and H. H. Goldsmith (eds.), Handbook of Affective Sciences: 85–870. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

April L. Wright is an associate professor of strategy and management at The University of Queensland. Her research explores the processes through which institutions are maintained, changed and disrupted, with particular focus on professional work.

Alan D. Meyer is Professor Emeritus of Management at University of Oregon. He uses organizational theory and sociology to study environmental jolts, industry emergence, field configuring events, and corporate venturing.

Trish Reay is Professor and TELUS Chair in Management at University of Alberta. Her primary research interests include institutional and organizational change, professional identity, and identity work.

Jonathan Staggs is a lecturer and post-graduate business coordinator at Christian Heritage College. His research explores the causal factors and actors that lead to institutional and industrial change.

“COVID-19 Response may depend on Strength of State’s Medicaid Program” by Josh Pacewicz

In the United States, state governments rather than federal agencies lead the fight against COVID-19. This is not simply because the Trump administration’s approach has been erratic. It is because the United States lacks a federal healthcare bureaucracy. And your state’s public healthcare system may be only as good as its Medicaid program.

Political sociologists have long argued that modern states depend on bureaucracies that translate central directives into street-level consequences and bring information about street-level realities to policy makers. But the United States is unusual in this respect: students of welfare regimes describe it as delegated, hidden, or divided in the sense that federal programs and goods are delivered via intermediaries like subnational governments, nonprofits, and tax policies. Programs like Medicare and Medicaid are a case in point.

This state of affairs introduces a legibility problem: no federal agency can both assess street-level conditions and direct a response. The United States lacks a universal healthcare program and, therefore, a national healthcare bureaucracy. And Medicaid is administered by states, Medicare by private sector insurance companies. In Britain, the National Healthcare Service (NHS) employs 1.5 million and could coordinate a national response. The American Center for Disease Control (CDC) employs 10,000 and acts mostly by issuing guidelines.

It is for this reason that day-to-day decisions about the coronavirus—when to initiate aggressive social distancing measures, who to test, where to divert scare resources—are being made by governors. And governors, and the rest of us by extension, depend on the expertise of an alphabet soup of agencies that are largely unknown to the public: the Texas Department of Health Services (TDHS), the Oregon Health Authority (OHA), and the like.

This is bad news for two reasons. First, state healthcare agencies have been subject to budget cuts for decades and have lost a quarter of their workforce since the Great Recession. And second, a successful national response to the virus depends on a successful public health response in all states—which seems unlikely as there are 50. If Virginia drops the ball and the virus rages out of hand, West Virginia will be impacted even if its response is exemplary.

Nevertheless, it is reasonable to ask which states will be more effective in their fight against COVID-19? I suspect that the answer will have much to do with their Medicaid programs.

Over the last several years, I have been conducting a mixed method research project that examines the diverging ways in which states implement federal policies. The project includes case studies of Medicaid in Rhode Island, New Hampshire and Kansas (in collaboration with Ben Merriman).

Many variables will likely shape a state’s response to the virus. For instance, states with large research universities that collaborate with state government should be more effective. But there are three reasons why Medicaid should be especially consequential: there is much variation in how states implement the program, the program acts as a training ground for a state’s pool of healthcare experts, and different types of Medicaid programs imply large variation in a state’s ability to assess and intervene in street-level conditions.

Variation in states’ Medicaid systems is large and growing. Medicaid is a grants-in-aid program, wherein the federal government acts by reimbursing states for Medicaid eligible expenditures. States can file waivers that allow them to selectively disregard federal statutes by delegating administration of the program to nonstate actors, covering additional populations or services, or imposing work requirements on Medicaid recipients. And, since the 1990s, use of such waivers has expanded, increasing interstate variation in Medicaid.

Students of Medicaid classify the result as 50 different healthcare systems. The gap between the highest and lowest spending Medicaid state is $2500 annually per capita, about as big as annual federal expenditures on social security (our biggest directly administered federal program). And interstate differences do not mirror blue and red state divides nor ACA expansion and non-expansion states—although my research suggests some divergence along partisan lines. For example, Nevada has been trending blue for years, but has one of the nation’s stingiest Medicaid programs.

Differences between states are not about expenditures alone; they reflect a different philosophy of healthcare delivery. Consider the three states that I have examined in detail: Rhode Island, New Hampshire and Kansas.

In Rhode Island, agency officials see themselves as engaged in a backdoor expansion of the social safety net: their aim is to maintain state budget neutrality while increasing the size of the program by integrating healthcare with social services. This allows them to achieve costs savings that can be reinvested in the program. They also free up resources for program expansion by using federal dollars to pay for existing state programs that improve health but stretch traditional definitions of healthcare (e.g., affordable housing supports, financial counseling, community centers and programs).

In New Hampshire, agency officials view healthcare as a problem of insurance regulation. They see Medicaid as a funding mechanisms for purchasing private-sector insurance or an insurer of last resort for those that are too expensive to cover privately.

And for much of the 2010s, Kansas sought to “privatize” Medicaid by delegating program administration to for-profit managed care companies—an initiative that achieved disastrous consequences for vulnerable populations like the developmentally disabled.

These different approaches to Medicaid shape the pool of healthcare expertise in each state. It is not easy to sustain a state-level career in public service and advocacy, and most successful healthcare experts spend at least part of their careers employed by state healthcare agencies or organizations that work closely with them. These career trajectories produce different epistemic communities. In Rhode Island, healthcare experts generally have backgrounds in advocacy or social service nonprofit work. In New Hampshire, healthcare experts are attorneys who specialize in insurance regulation. Kansas’s healthcare experts disproportionately have backgrounds in hospital administration, GOP politics, and right-wing think tanks.

These inter-state differences translate into different public healthcare capacities. Rhode Island’s approach to Medicaid depends on targeted healthcare interventions, and agency officials achieve this capacity by building relationships with social service agencies and nonprofit community groups via formal and informal collaborations, institutionalized agency working groups and the like. Such minute details about the population are important during an outbreak, because successful suppression depends on authorities’ abilities to identify subpopulations wherein the virus is likely to rage out of control—as in California, where officials preemptively moved the state’s unhoused population to motels and hotels.

Such public health interventions will surely be more difficult in states where officials have delegated program administration to third parties—and therefore have limited knowledge about the state’s population, lack relationships with nonprofit groups that could get them such information quickly, and have limited experience initiating public health interventions.

The COVID-19 crisis has led many observers to the conclusion that one’s wellbeing depends on the wellbeing of society’s most underprivileged. The same may be true of our political institutions: your state’s public health response may be only as good as Medicaid, a program that usually impacts only society’s poorest and most vulnerable.

Josh Pacewicz is an Associate Professor of Sociology and Urban Studies at Brown University.

“Diversity in Response: How State Governments Disseminate Information about Coronavirus” By Kevin Hans Waitkuweit

The spread of COVID-19 across the globe has led to an array of responses to the second pandemic of the 21st century. Medical responses have varied across nations as the virus has spread, with various political and medical infrastructures in countries around the world being tested in their ability to respond to a crisis. One critical aspect of any nation’s response is in how governments are keeping their populations informed of the virus. In the case of China, researchers raise concerns over how the Chinese government is reporting COVID-19 cases (Cyranoski 2020). On the other hand, countries like South Korea are using the dissemination of information on the virus as a tactic to mitigate the virus’s spread (Parodi et al 2020). In the United States, critiques of the inactivity and slow-moving pace of the federal government— through actions such as sidelining the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Sun 2020)—has left the management of the coronavirus at a local and state level. The result in the case of the US is that state governments are working to keep the public informed via a mixture of case counts on specific COVID-19 webpages, phone banks, and social media websites. I argue that each state is using the resources it has to create a multilevel approach to informing the public.

In the case of how each state functions, it has been well-documented in research that healthcare resources differ from state to state, which has been done to the point that rural health is its own field of analysis (Hartley 2004: 1675). Regarding the current pandemic, these differences in resources manifest through how each state is responding to the task of keeping their residents informed of the virus. Nevertheless, despite these differences in response and focus, it is apparent that there does exist a general consensus that the number of cases should be released to the public.

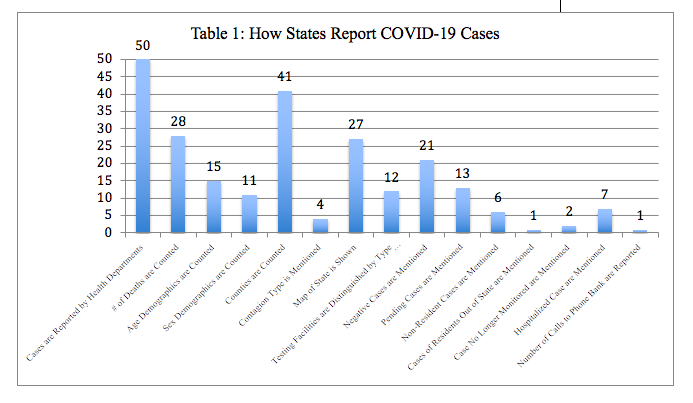

As table 1 demonstrates above, all of the 50 states are releasing information on the number of cases but only some release demographic information for their respective cases. All states have their health department publicizing the numbers on their websites. Yet there also exist states reporting only one aspect of information. For example, New Jersey is the only state to publish information on the number of calls their phone banks are receiving from their residents. Other data in table 1 demonstrates that a majority of states (41/50) are reporting which counties have cases. Additionally, 21 states are reporting the negative cases that they have in their state. At the minimum, states are reporting the number of cases, but since there is no standard in how information of cases should be reported, there exists variation across states in regards to the amount of detail each state is giving on their respective cases.

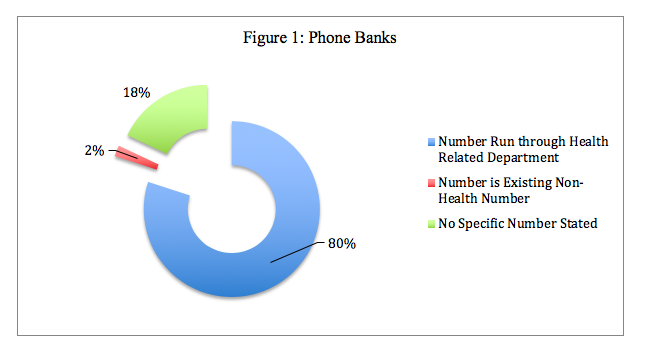

Another response to the need to provide accurate information to the public has come in the form of a majority of states setting up phone banks to handle calls and answer questions from concerned citizens about COVID-19. As figure 1 demonstrates below, a majority of states have relied on existing infrastructures to handle calls.

One telling sign of the adaptability of states is represented in how the state of South Dakota—represented by the 2% in figure 1—is repurposing its Office of Highway Safety to act as the point agency for its COVID-19 phone bank. In this case, the state of South Dakota is repurposing one of its non-health related offices to fill the health needs of the state. The impact of phone banks as a source of information is yet to be seen.

The importance of communication is also demonstrated through how states use social media. In examining each health department’s social media presence, all states’ health departments have and are using their Twitter accounts to share updates and information on the virus. As for Facebook, 49 out of the 50 states’ health departments are actively using Facebook to share information with their residents as to their individual state’s response and suggestions for proper care in regards to the virus. Given this brief overview of the social media presence of each state further analysis of the function of social media as a tool for government action is needed.

As the virus continues to spread, it becomes apparent that there does exist some uniformity in the idea that information needs to be disseminated across the states. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention has not provided guidelines as to how information on the virus should be shown to the public. Nevertheless, states have found a way to provide a multitude of sources for their residents to obtain information. During these anxious times, the ability of governments to respond to a pandemic and keep their populations informed is of the utmost importance. Every state’s actions demonstrate that all states in the US see a well-informed public as an asset to work towards flattening the curve and reducing COVID-19’s impact on our healthcare system. Each state is using the resources that it has available to it, leading to a diversity in response regarding how each state is informing its residents of COVID-19.

References

Cyranoski, David. 2020. “Scientists Question China’s Decision Not to Report Symptom-Free Coronavirus Cases.” February 20. Nature. Retrieved March 15, 2020 (https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-00434-5).

Hartley, David. 2004. “Rural health disparities, population health, and rural culture.” American Journal of Public Health 94(10). 1675-1678.

Parodi, Emily, et al. 2020. “Special Report: Italy and South Korea virus outbreaks reveal disparity in deaths and tactics.” March 12. Reuters. Retrieved March 16, 2020. (https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-response-specialre/special-report-italy-and-south-korea-virus-outbreaks-reveal-disparity-in-deaths-and-tactics-idUSKBN20Z27P)

Sun, Lena H. 2020. “CDC, the top U.S public health agency, is sidelined during coronavirus pandemic” March 19. Washington Post. Retrieved March 19, 2020. (https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/2020/03/19/cdc-top-us-public-health-agency-is-sidelined-during-coronavirus-pandemic/).

Kevin Hans Waitkuweit is a graduate student in the Department of Sociology at the University of Notre Dame.

“Rural Healthcare and the Coronavirus Pandemic” by Derrick Shapley

In the United States today, many rural areas are facing a crisis in healthcare. A report by Jessica Seigel for the National Rural Health Association in 2019 finds that 98 rural hospitals have closed since 2010 and that 46 percent of rural hospitals operate at a loss. According to the rural healthcare association, there are only 39.8 doctors per 100,000 residents in rural areas compared to 53.3 in urban areas. Rural areas tend to have an older population, which makes them more susceptible to needing medical attention the rural/urban divide on healthcare becomes greater.

This country has been fortunate during the Coronavirus pandemic that we have not; as of the date of this publication seen a spreading of the virus in rural areas, we cannot and must not assume this will be the case in the future. There are five major reasons for the rural healthcare crisis.

- Many states that were largely rural did not accept Medicaid funding after passage of the affordable care act. The Kaiser foundation found that Medicaid expansion led to coverage gains in rural areas that would also help fund hospitals who lose funding due to patients who enter the emergency room for treatment but have no coverage. Medicaid also plays a crucial role in filling in the gaps in rural areas because rural areas have people who are less likely to have private insurance.

- Isolation of rural areas. Naturally, since rural areas by design or known to be away from city centers they are further away from clinics, hospitals, and even specialists that can assist in healthcare needs. Rural areas also tend to be poorer and have less public services such as police, firefighters, EMT’s, etc. this leads to further travel for rural residents and increased transportation costs. In some ways during a pandemic, the isolation of rural areas can be advantageous because there is less direct contact with residents and especially unknown residents on a day-to-day basis.

- An aging population. As was mentioned earlier rural areas tend to be older than their suburban and urban counterparts, which leads to increased health.

- Limited access to healthier foods. Many rural areas are have become known as food deserts. This implies rural residents have less access to supermarkets to provide healthier foods and more nutrition.

- Lack of broadband access. According to the American Bar Association, approximately 25 million Americans overwhelmingly in rural areas lack high-speed internet access. High-speed internet access is crucial for rural health for not only informing residents but also creating contact opportunities through Telemedicine. Since broadband and cable access are often not profitable in rural areas, many private companies do not invest resources in these areas.

The problems above are disturbing when combined with a pandemic like the coronavirus, which has higher mortality rates among the elderly. While the social and physical isolation of the residents of rural areas is a benefit in making it more difficult for pandemics to reach rural areas, if they do reach these areas, it becomes a curse.

The question now becomes what are some solutions and actions for alleviating these problems. One simple solution is that states or the federal government can expand Medicaid. However, the practicality of Medicaid expansion happening since states with large rural populations tend to be conservative who have a mistrust of government programs is in dispute. According to Kunai Sindhu at Quartz, in 1997 as part of the Balanced Budget Act there was a cap instituted on the number of medical residents at teaching hospitals. While there has been an increase of MD’s by over 30 percent in this country since 2002, it has not been enough to match a growing need with an aging population. In the United States, there has been a recent increase in the number of medical schools from 2000 to 2020 there have been 31 new medical schools (this does not include osteopathic medical schools) and many more are in the works. Increasing the number of medical schools is a benefit to the population but there needs to be a lifting of the cap of residents. This may cause more physicians to locate to poor and rural communities because most medical school students pay for their tuition through student loans and there are forgiveness plans for working in rural or impoverished areas.

Increasing rural access to broadband services is crucial in times of pandemics. Increasing rural access occurs through two options similar to what Alabama has done; the state can create a fund, which works with public utilities and cooperatives in rural areas to create broadband service; or Cities, States, or the Federal Government can create a public broadband service themselves. Many states have banned local public broadband so this moves the responsibility to either the state or federal government to perform these duties. Allowing access to broadband will also increase services to telemedicine and telehealth programs, which may become the future of healthcare during a pandemic crisis. The nature of a pandemic involves a disease that is highly contagious and often those that are among the first to get the disease are healthcare providers, physicians, EMT’s and nurses. By reducing face to face contact with those who are highly contagious we can maintain a strong healthcare system.

We must seek to strengthen and develop our rural infrastructure and healthcare system. With the crisis that has recently occurred in our country our rural healthcare system is in dire need of modernization. The public policy proposals provided in this article are not meant to be limiting to others but the start of a conversation for change in our rural communities. If we are, to be prepared for the next pandemic we must come to the realization that our healthcare system and infrastructure in rural areas are not sustainable in the long term.

Recommended Readings

https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/resources/publications/factsheets/rural-health.htm

https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-role-of-medicaid-in-rural-america/

https://www.asaging.org/blog/rural-america-faces-shortage-physicians-care-rapidly-aging-population

https://www.ruralhealthweb.org/about-nrha/about-rural-health-care

Derrick Shapley is the Department Chair of Sociology at Talladega College. His interests include rural inequality, Rural Health, Rural Stratification, and Political Sociology.

“Immigrant Health and COVID-19 in the United States” by Meredith Van Natta

During a surreal Democratic debate dominated by COVID-19, candidates Biden and Sanders were asked how they would ensure that immigrants in the U.S. feel safe enough to get treatment and stop the spread of coronavirus. Biden proposed assurances of safety to anyone seeking testing or treatment, while Sanders pitched universal health care, reduced immigration enforcement activity, and renewed immigration reform efforts.

Such proposals depart sharply from current immigration and health policies that are now clashing against the unprecedented challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic. For the past five years, I have been studying how immigrant patients and the clinicians who provide their care balance the risk of illness and injury against the threat of detention, deportation, and family separation. As immigration enforcement activities have accelerated, and as fear and uncertainty have increased in recent years under “zero tolerance” policies (DOJ 2018), the public charge rule change (83 FR 51114), and enhanced biometric surveillance of migrants (85 FR 13483), I have witnessed U.S. immigration policy undermine clinical care across the country.

Existing research demonstrates that legal status is a fundamental determinant of health (Castañeda et al. 2015, Quesada 2011) and emphasizes the health consequences of exclusionary and criminalizing policies for immigrant individuals and communities (Horton 2016, Marrow & Joseph 2015, Kline 2019) in ways that are highly racialized (Asad & Clair 2017). My colleagues and I have also shown how federal immigration laws stratify immigrants’ health chances at the local level (Van Natta et al. 2019) and how federal immigration and health laws harm immigrant patients and compromise clinicians’ ability to equitably serve patients with varying legal status (Van Natta 2019).

The COVID-19 pandemic is taking place in a national context in which contemporary health, welfare, and immigration reforms increasingly exclude noncitizens. Many noncitizens cannot get insurance through their employer, and unauthorized and authorized immigrants living in the U.S. for under five years are excluded from Medicaid coverage and many marketplace options (KFF 2019). As an ethnographer studying the relationship between citizenship and health, I have closely observed immigrants’ health negotiations in multiple U.S. states with vastly different policy contexts. I have shadowed clinic workers in clinics and attended public gatherings that address immigrant health. I have also conducted in-depth interviews with patients, providers, and clinic workers across the country to understand how different parties are making sense of rapidly changing policies when an immigrant patient’s health is at stake.

This work reveals several issues salient to life in a protracted pandemic. Foremost is the reality that the Trump administration’s commitment to aggressive immigration enforcement while rolling back the health protections of the Affordable Care Act destabilizes people’s ability to prioritize health over personal and family security. Even where local jurisdictions have enacted immigrant-inclusive policies such as sanctuary ordinances and universal health care, federal immigration enforcement has accelerated nationwide. Additionally, haphazard policy enactment has resulted in widespread confusion, making it difficult to separate reality from hype as immigrants make critical decisions about their health.

Further, I have spoken directly with immigrants who have forgone health care out of fear, as well as with providers who have struggled to enact the standard of care for immigrant patients. Patients often describe avoiding involvement with government agencies for health and social benefits, even if this harms their health. Many are facing serious illness now because they could not get the care they needed – particularly among those with diabetes who have endured amputations, dialysis, and other complications of advanced illness. Healthcare providers have expressed frustration over patients’ ineligibility for health services and confusion over whether their clinics can remain a safe space for undocumented patients amidst aggressive immigration enforcement. Multiple providers have described undocumented immigrant patients “waiting until they’re at death’s door” before seeking health care for fear of immigration enforcement. In one extreme case, a nurse I spoke with had to persuade an undocumented woman who was having a heart attack at the hospital’s threshold to come inside the hospital where they could treat her. If someone is willing to forgo care in such an immediate emergency, is it likely they will seek treatment for a fever and cough (two of the telltale symptoms of COVID-19)?

At a time of pandemic, when an individual’s decision about whether and when to seek care has exponential implications for society’s health, this level of fear is unacceptable. There are steps that can and must be taken to ensure everyone’s health, regardless of one’s immigration status. We can start by learning from the clinics I have observed. These clinics have developed an institutional culture that makes clear that patients do not have to disclose their immigration status in order to get care. They use welcoming language – both in speaking with patients and in the multi-lingual signage around their facilities. Before asking for personal information or financial or identity documents, they ask patients what they need for their health. They facilitate the provision of care rather than gatekeeping healthcare resources, an approach which is essential during this time of crisis. They also stay on top of policies that impact their patients, such as providing up-to-date guides on public charge. These clinics can leverage their knowledge and trusted relationships with communities to communicate life-saving policies as they come into effect.

Institutional culture can only go so far, however, if the policy context does not adapt to meet the realities of coronavirus transmission. The Trump administration should announce clear and definitive changes to immigration enforcement and emphasize across all media the following changes, some of which are currently underway: the suspension of public charge penalties, the release of vulnerable migrants from immigration detention facilities, and the suspension of immigration enforcement operations and in-person immigration processing. Just as immigration enforcement agencies have discretion to suspend ongoing actions in the event of natural disaster, the Department of Justice should prioritize human life over political posturing at this time of international crisis. Failing to do so now will put everyone at risk, regardless of their immigration status.

References

Asad, Asad, Clair, Matthew. 2017. “Racialized legal status as a social determinant of health. Social Science & Medicine doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.03.010

Castañeda, Heide, Holmes, Seth M., Madrigal, Daniel S., DeTrinidad Young, Maria-Elena, Beyeler, Naomi, Quesada, James. 2015. “Immigration as a Social Determinant of Health,” Annual Review of Public Health 36: 1.1-1.18.

Federal Register. 2018. “Inadmissibility on Public Charge Grounds: A Proposed Rule by the Homeland Security Department.” Oct. 10, 2018. Accessed Oct. 11, 2018. (https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2018/10/10/2018-21106/inadmissibility-on-public-charge-grounds)

Federal Register. 2020. “DNA-Sample Collection From Immigration Detainees.” Mar. 9, 2020. Accessed Mar. 20, 2020. (https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/03/09/2020-04256/dna-sample-collection-from-immigration-detainees)

Horton, Sarah. 2016. They Leave Their Kidneys in the Field: Ilness, Injury, and Illegality among U.S. Farmworkers. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Kaiser Family Foundation. 2019. “Key Facts about the Uninsured Population”. Accessed Jan. 19, 2020. (https://www.kff.org/uninsured/issue-brief/key-facts-about-the-uninsured-population/)

Kline, Nolan. 2019. Pathogenic Policing: Immigration Enforcement and Health in the US South. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Marrow, Helen B. and Tiffany D. Joseph. 2015. “Excluded and Frozen Out: Unauthorised Immigrants’ (Non)Access to Care after US Health Care Reform,” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 41(14):2253-2273.

Quesada, James, Kain Hart, Laurie, Bourgois, Philippe. 2011. “Structural Vulnerability and Health: Latino Migrant Laborers in the United States.” Medical Anthropology 30(4): 339-362. doi: 10.1080/01459740.2011.576725

U.S. Department of Justice. 2018. “Attorney General Sessions Delivers Remarks Discussing the Immigration Enforcement Actions of the Trump Administration.” Address to the public, May 7, 2018.

Van Natta, Meredith. 2019. “First Do No Harm: Medical legal violence and immigrant health in Coral County, U.S.A.” Social Science & Medicine. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112411

Van Natta, Meredith, Burke, Nancy J., Yen, Irene H., Fleming, Mark D., Hanssmann , Christoph L., Rasidjan, Maryani Palupy, and Shim, Janet K. 2019. “Stratified Citizenship, Stratified Health: examining Latinx legal status in the U.S. healthcare safety net.” Social Science & Medicine. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.10.024

Meredith Van Natta is a medical sociologist and postdoctoral associate at Duke University’s Science, Law & Policy Lab (SLAP Lab) where they study the intersection of citizenship and science, medicine, and technology policy.

“The Resiliency of Community Pandemic Preparedness” by Ry Brennan and the Members of Bonfire Collective

The typical watchword of infectious disease is immunity, but in the face of the coronavirus, no one can claim immunity for sure. Instead, the tactic promulgated by specialists is to flatten the curve. Have people get sick slower, temper the demands on our social infrastructure so they can withstand weeks and months of slow disaster. In short, we need resilience. The authors draw on our experience organizing as an affinity group and our scholarship of infrastructure to make a decentralist argument for local autonomy, relocalized supply chains, and horizontal networking to manifest resilient social infrastructures.

Resilience as a Local Capacity. From the standpoint of communities, centralized power structures situate decision-making and resources always elsewhere in the hands of someone else. Local agents have no control over centralized structures. When these structures prove untrustworthy, such community disempowerment is disastrous. Our affinity group has spent years working to articulate this core assertion to other progressives. After Trump’s inauguration, we hosted countless meetings packed with neighbors terrified of what the malice and incompetence unleashed at the federal level could mean for causes they cared about. We started to plan for how local governments and civil society networks could protect what we feared losing in the years ahead. We didn’t know which way the federal leviathan would turn its jaws, but we knew we needed to amass power locally to fight where we stand.

Now the federal government has led us into perhaps the most widespread threat we have faced together. More than ever we look to our local institutions to respond to our needs. The Santa Barbara City Council Meeting on March 10th was dedicated to a panel of public health officials discussing their response to COVID-19. From their reports, we learned what was working and which systems might fail dramatically. These promises and perils align with basic decentralist assertions about local resilience.

Necessity of Local Autonomy. In his Normal Accidents, Charles Perrow (1999) asserts that failures are hardwired into systems that are both interactionally complex and tightly-coupled. When facing a pandemic, the ‘system’ is necessarily complex because we live in a complex society; so to avoid normal accidents, we must avoid tight-coupling. In tightly-coupled systems, once processes are initiated, things happen very quickly and cannot be turned off or isolated. Tight-coupling usually works fine in linear systems. But when managing complex systems, the wrong call can precipitate countless chain reactions sending out ripples of dysfunction. Thus, instead of one decision-maker calling shots from afar, Perrow’s solution is to create loosely-coupled, decentralized systems. Here, decisions are made by local actors who are most knowledgeable of the system’s complexity and are able to act autonomously.

In the context of COVID-19, autonomous local action is essential. At City Council, our County Public Health Officer defended his prerogative to diverge from the recommendations of the CDC, which at the national level is slower to react and less informed of on-the-ground developments. Over the course of the week, the local school district shut down, as did countless others across the country. They did not wait for federal direction: they responded based on local knowledge and community concerns. When the hulking power amassed at the federal level failed to swing into action, thousands of decentralized agents were ready.

Relocalized Supply Chains. California has recently witnessed a spate of wildfires and electric power shut-offs caused by poorly maintained, PG&E-owned power lines. These related crises demonstrate what Lorenzo Kristov (2018) has argued in his work on distributed energy systems: centralized production of electricity leaves end-users vulnerable to fragilities in elongated transmission-line systems. When an electron is generated at a plant, then sent zipping down scores of miles of power lines draped over dessicated chaparral, much can happen to prevent that electron from safely reaching its end-user. It might start a fire on the way. In light of recent calamities, energy experts are realizing that it’s usually safer to make energy closer to home.

The problem with energy supply lines is analogous to medical supply lines. Our hospital relies on medical equipment sourced from China, and these supply lines have been disrupted by the pandemic. Our economy is built on the fiction that global trade is efficient, and we have largely failed to recognize that vast dissociation of sites of production from sites of consumption implies a fragile system. Amidst crisis, global networks may simply fall apart. Producing what we need closer to home and diversifying our local economies can help us remain resilient when supply chains are jeopardized. With Paul Goodman (1965) and Murray Bookchin (2005), local diversity is the crux of resilience and adaptability: simplified economies will not fare well when communities are isolated.

Horizontal Networks. Of course, as our affinity group knows well, we cannot overcome crisis alone: communities must be capable of linking up with broader networks to share resources and knowledge. Our local public health department is autonomous, but it constantly shares knowledge with institutions around the world. While material supply chains should be relocalized, both to bolster community resilience and end the ravages of global capitalism, now more than ever we need to forge global bonds of solidarity to combat not just the pandemic but the wave of austerity measures that will likely follow. Our intention here is not to scale-up, ceding our power to more centralized entities; instead, we focus on how to scale-out through horizontal networks of solidarity.

Beginning that work of scaling-out can start quite small. Our affinity group started with just a handful of committed organizers with deep respect for each other. We have spent years developing capacities for media-sharing, mutual aid, and a set of institutional connections that will prove fruitful in the weeks and months ahead. Having a strong foundation for trust and a ready-made set of tactics has meant that we could mobilize quickly. When COVID-19 struck California, we were already in a meeting.

References

Bookchin, Murray. 2005. The Ecology of Freedom. Oakland, CA: AK Press.

Goodman, Paul. 1965. People or Personnel? New York: Random House.

Kristov, Lorenzo. 2018. “Resilient Community.” Draft for Discussion. Academia.edu.

Perrow, Charles. 1999. Normal Accidents. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Ry Brennan is a doctoral student studying Sociology at University of California – Santa Barbra.

“Viruses Don’t Care about Borders” by Joseph Harris

The rapid spread of the coronavirus in the U.S. took us by surprise. But it shouldn’t have. The historical trajectory of the epidemic in other countries and their accumulated experience fighting it actually should have prepared us to respond more effectively. Yet, U.S. institutions at all levels have proved slow moving and unable to respond quickly.

Why have we moved so slowly? And how can we learn from our mistakes to ensure future response to diseases are stronger?

I conduct comparative historical research on national responses to epidemics and teach courses on globalization. I am also co-founder of the ASA’s Global Health and Development interest group. More than most, I am well aware of the fact that the world’s next big pandemic is just an airplane flight away.

While it was clear to me early on what was coming, seeing our institutions and leaders wake up to the crisis weeks later has been like watching a nightmare unfold in real time.

Their responses in the face of what we should have known was coming had we been watching more closely have been even worse. Even more dispiriting has been learning that the first instinct of some officials who were elected to protect the public interest has been to profit from the knowledge of what was coming rather than to help America prepare for it.

The coronavirus has laid bare just how resistant humans are to change. In the face of evidence, we sometimes prefer to continue down familiar paths, clinging to our routines, rather than confronting what the evidence tells us. This dynamic plays out in our individual lives but also within the institutions we inhabit.

In social science, the term “path dependency” refers to the way in which the choices we make at one early point in time can be self-reinforcing and channel us along a particular path, foreclosing alternative possible paths. Early actions (and inactions) can prove highly constraining and help account for how and why policy choices made early on become “locked in” and prove resistant to change later.

The U.S. response to COVID-19 illustrates the power of path dependency and suggests the need to be more aware of social dynamics that can lead us to continue down a path of business as usual in the face of foreboding evidence.

In the early days of the epidemic, we operated according to precedents set by an existing social reality that did not yet (visibly) contain COVID-19. The experiences of other nations devastated by the epidemic – including China, South Korea, Iran, and Italy–seemed far away. However, Italy and South Korea’s experiences in particular, as industrialized nations with healthcare systems that are comparable or superior to our own, should have gotten our attention.

When we could have been preparing, we ignored the experiences of other countries, in part due to our own imperial hubris and a desire to put what was out of sight out of mind.

Our response was further imperiled by a president invested in maintaining a bull market in an election year. He and other Republican leaders played down the epidemic as a “hoax” and suggested there was no need to be alarmed. Right-wing media amplified this message. While this refrain eventually changed, it was only after misinformation reached an impressionable public, desensitizing people to risk.

Even more critically, lack of testing and overly narrow testing criteria meant that the very disease surveillance institutions whose job was to wake us up did not prompt us to reconsider the path we were on.

Historically, the success of our disease surveillance system has revolved around effective testing. Yet, in this epidemic we continued to take our cues from these institutions despite the fact that they were not accumulating statistics on prevalence in the usual manner. In addition, their own guidance may have contributed to community spread.

Until February 27, CDC guidelines allowed doctors to test suspected coronavirus cases “only if they recently traveled from China or had contact with someone known to be infected.” Yet, in an era of globalization, we know that diseases don’t respect borders and can pass from person to person easily. We do not need to travel to China ourselves to be infected by someone whose exposure was several degrees removed from what was listed in the testing criteria.

Narrow testing criteria likely contributed to community spread by allowing cases to go undetected. Yet, even after loosening CDC guidelines, local health authorities continued to constrain attempts by physicians to test suspected cases that fell outside these guidelines.

Reports then surfaced that the disease had likely been circulating in the U.S. for weeks. This too could have been our wakeup call, since genetic typing provided evidence that community spread was already happening. But without immediate strict quarantine measures and the imposition of domestic travel restrictions within the U.S., the disease spread further.

By March 7 and even later, health officials in Boston continued to state that the risk was low, even though lack of testing meant the evidence base for that pronouncement was dubious at best.

Whether we see it or not, COVID-19 is here. It has likely been here for some time and will remain with us for some time. I have not been to my office for two weeks and began to teach classes online last week, learning to balance work with homeschooling my boys.

Based on the trajectory of the disease, I know the ugly reality that lies ahead. Many people will die. Our healthcare system will be overwhelmed, and economic devastation will be enormous.

If this epidemic teaches us anything, it is that we need to be more mindful of the way in which the past powerfully shapes the present, since it’s all too easy just to sleepwalk into the present. I am glad our institutions have finally waken up. I just wish they would have sooner.

Joseph Harris is an Assistant Professor of Sociology at Boston University.

Comments 16

Tamara Riot

March 30, 2020greetings men! Thanks for sharing, I was looking for exactly this info, however I could not discover it because I'm dreadful at Web points. You know, I'm not young any longer, institution of higher learning times ended very long time ago. Nonetheless, my old good friends have vehicles and also apartments; I only have my dog and old shoes. Someday I was resting as well as believing why am I such a looser, but one my friend told me that he never ever functioned and he is making money on playfreeslotoreview.com . I was stunned, I might n`t believe that you can make money in this manner. But I tried and I did it! Try it yourself

chrisgail

April 9, 2020We have to wear a safety kit to keep safe from harmful diseases. I appreciate your efforts to share useful tips for our health.

cheap dissertation writing service

bandar capsa susun idn

April 22, 2020Hello!

My name is Maximilian and I'm a 29 years old boy from Fairlop Waters. https://www.evernote.com/shard/s552/sh/88b4f2fc-0422-de67-9702-b2a134f98adc/4fb050b8600ae8cdab052fe07bde7253

pikachu chu

May 5, 2020Your post is great and engaging, the content is very practical, and gets people's attention. Thank you for sharing. mapquest driving directions

noewa

May 8, 2020good blog, I have actually just review two or 3 short articles, however i'm currently captivated with your spirit and your knowledge. When it pertains to betting experience, the online casino experiences in all fields of on-line gambling establishment which has actually triggered the staff to enhance their services and graphics much better than the newly developed online gambling enterprises. Producing an account is rather an easy procedure, you simply require to upgrade the forms with the essential details needed as well as proceed to the following stage.Your progress does n`t matter, people need to find the most significant benefits to make their life much better as well as loaded with cash. Our casino platfrom has whatever, you just need to go to freeloginmobileonline.com and begin to play.

Jake

May 12, 2020https://contexts.org/blog/healthcare-and-critical-infrastructure/comment-page-1/#comment-301216

aric walker

June 30, 2020This is a very interesting document. Me and my friends have read them and find them really helpful. I will refer more about this article. Thanks.

surviv io

Tommy Mellor

August 19, 2020Such good information about it. b2b marketplace

Marshall M. Padilla

August 20, 2020There are a great deal of bettors nowadays, including both skilled gamers and those that only think of beginning their gaming occupation. When a gamer is in deep search for the best choice in the location of betting, he/she takes notice of all the attributes that the chosen casino can supply him/her with, consisting of the get rid of incentive programs as well as promotions. If you have any type of inquiries including those that touch no deposit incentive programs, prizes for incentive code going into, incentives in the form of cost-free rotates and so on, you have actually involved the gold area. As you can see, Genesis Casino Review has a great deal of functions where you can capitalize, however the decision is still approximately you. If you want to have fun with Genesis, it does not matter where you are from, whether it is Canada, it is New Zealand or it is any other country.

Pe Jeain

August 27, 2020Excellent post! the author have shared the unique content in blog. hongkong b2b marketplace

Jack buttler

September 10, 2020It's an amazing site and thanks for share a great content.

https://couponado.com/

Amber

September 15, 2020About encoding - I don't know about magic means, frankly speaking, I haven't heard anybody finally get rid of the craving for alcohol with its help. Usually, after a while, everybody snaps again. On the other hand, I can recommend a vipvorobjev hospital here that helped my brother get rid of his addiction. Although it's no surprise. So not only did my brother get rid of his craving for alcohol, but he also cleaned up his body completely. In general, I advise you not to experiment with encoding, but better to try this tool, I think it will be much more effective.

Aloin Chartier

October 12, 2020Check Profile - https://about.me/AloinChartier

Gerry Truwer

October 21, 2020Google Profile: https://www.google.com/url?q=https://ussitedir.com

Ruth Beaudin

October 27, 2020I am getting afraid day by day. Corona virus has a mysterious power to ingest into human connective tissue which lies in the respiratory track of human. So first symptom could from common cold sore throat etc. You may Visit https://www.bestfreesexgames.co.uk/ to know more information that will let them know how to play adult online games.

Markus1

November 15, 2023https://contexts.org/