Humor, Risk, and Black Twitter: Insights from the 2014 Ebola Outbreak

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, social media was criticized as a source of misinformation and conspiracy theories and, more recently, as a risk to youth mental health. We do not dispute these claims, but it is important to acknowledge the diverse functions of social media participation, particularly during outbreaks.

As we found in our study of digital emotions during the 2014 Ebola outbreak, people do not simply use social media to share and receive information. They also use social media to participate in what emotions scholar Katrin Döveling and colleagues term “digital affect cultures.” In other words, social media platforms function as socio-emotional spaces where belonging, solidarity, and emotion management take place.During a public health threat, many emotions circulate online. Our study on social media discourse during the 2014 Ebola outbreak revealed that humor was the most common response among English-language tweets. Further, we discovered that several of the most popular humor tweets used AAVE (African-American Vernacular English) and referenced Black celebrities and/or cultural moments, forming a part of Black Twitter—an influential community and communicative style that media studies scholar and commentator Marc Lamont Hill describes as a “digital counterpublic.” This led us to ask, what various types of digital humor emerge during an outbreak? And how does humor help negotiate themes of risk, contagion, and connections with others, particularly within Black Twitter?

We analyzed a corpus of 47,955 tweets from the weeks surrounding and following the first Ebola case in the United States. One major category of humor-based tweets emphasized retreat and isolation, with references to moving “to the moon” or “I’m never leaving my house” as well as fatalistic acceptance of death (“I’m going to die,” “goodbye world,” and “Ebola victims rising from the dead . . . ok. Cool”).

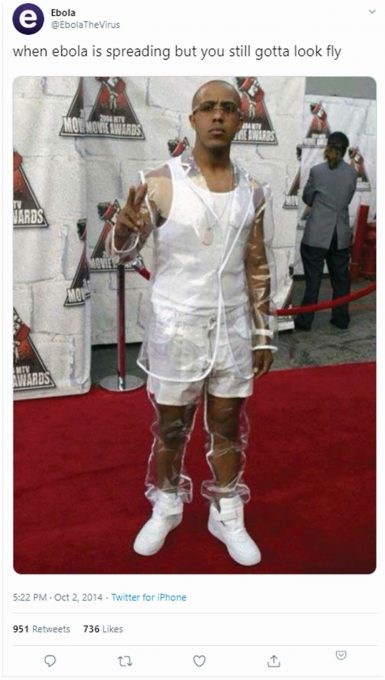

By contrast, Black Twitter humor—defined as tweets using AAVE, referencing Black celebrities, and/or Black cultural moments—focused on the tensions that arise when a community places high value on social relationships and is experiencing the added risk of contact with others. For example, the tweet below featuring Marques Houston brought back a memorable cultural moment in which the celebrity was roasted for his strange fashion choice. Underlying the joke is an emphasis on innovative and ridiculous fashion that allows for public life to continue despite the risks.

In another popular example of Black Twitter humor about Ebola, a picture shows a Swisher Sweet blunt cut into small pieces, with the text “From now on there will be no more passing the blunt due to ebola everyone gets a piece of the blunt.” This humor again emphasizes the value of social connections to the point of maintaining collective smoking sessions while introducing modifications to reduce risk.

While our study focused on the 2014 Ebola outbreak, we readily found similar examples of Black Twitter humor in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, in some cases following a similar pattern of referring to Black celebrities and innovations to minimize the risk of social gatherings. In one example, an image of R&B singer, Omarion, was circulated anew as the COVID-19 Omicron variant emerged.

There were also examples of COVID-19 humor that included the use of PPE (personal protective equipment) in public spaces:

Similar to the “pieces of the blunt” tweet that circulated during the Ebola outbreak, the same idea would circulate during COVID-19, with two women on Instagram sharing a video in which they cut a joint into two pieces to jokingly minimize risk. As they cut it, they count to three, each holding a side. Both smile and laugh as they take their “mini joint.”

In our analysis of Twitter humor during Ebola, we follow other studies of disaster humor to argue that humor involves more than simply coping with the fears associated with a biomedical threat like an epidemic. Humor allowed communities to share emotional energy, reaffirm values, and redraw the lines between insider and outsider. We see hints that Twitter served a similar function during the more recent global health crisis of the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, Black healthcare workers used tweets and humor in COVID-19 vaccine campaigns. Together, these findings illustrate how social media can facilitate belonging, solidarity, and emotion management in highly charged times.

Marci Cottingham is in the Sociology Department at Kenyon College. She is the author of Practical Feelings: Emotions as Resources in a Dynamic Social World.

Ariana Rose received her master’s degree in sociology with a focus on social problems and policy from the University of Amsterdam. She currently studies consciousness and neurodiversity.

Comments