Race and Rachel Doležal: An Interview

In June 2015, I got an email from a California radio station asking me for an interview about a person I had never heard of: Rachel Doležal. I quickly Googled her, and based on a brief news item, agreed to the interview. She seemed to be a White woman passing as Black, working as the president of the Spokane NAACP chapter to boot. I didn’t really see why this was national news, but I figured even a fluff piece could be an opportunity to foster public conversation about the fluidity of racial identities and the constructed nature of racial categories.

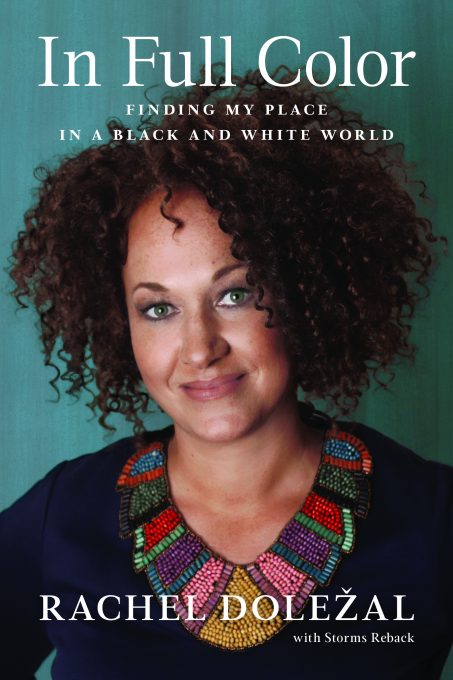

The slow summer news day turned into a weeklong media frenzy, with shockingly intense public attention focused on Ms. Doležal’s racial self-identification. My Soc 101 lesson about racial construction turned into a dozen interviews with incredulous reporters, fascinated by the notion of “transracial” people. And based on Ms. Doležal’s comments at the time as well as her new book, In Full Color: Finding My Place in a Black and White World, the term “passing”—with its connotation of masquerading—couldn’t quite capture the gradual and deeply-felt process of Black affiliation that she underwent. In my view, she is not a passer—someone who seeks to turn existing racial categories to their advantage—so much as a person who rejects widespread beliefs about the criteria for racial categorization.The concept of race as a social construct is one that Rachel Doležal invokes repeatedly as she explains and defends her self-identification with a race different from the one claimed by her biological parents. Is she wrong? Has she misinterpreted something fundamental to our discipline’s contemporary teaching on race? And can her case shed any light on the millions of people who alter their racial self-reporting from one decennial census to the next, according to research by sociologist Carolyn Liebler and colleagues at the U.S. Census Bureau? I expect sociologists will vary in their answers to these questions, but I also suspect that many of us have found a teaching opportunity in what Rogers Brubaker calls “the Doležal affair.” I’m grateful that Doležal agreed to share an advance copy of In Full Color and answer a series of questions for the Contexts audience.

Ann Morning: First of all, why did you decide to write In Full Color?

Rachel Doležal: If I’d had the choice, I would have waited to share my story until much later in life. But, with the world clamoring for an explanation and justification for my identity, I felt the task was prematurely thrust upon me. I wrote In Full Color not only to set the record straight about who I am but also to further the dialogue about race, encourage others to be exactly who they are, and to document my journey for my sons. While my journey could have catalyzed a thoughtful discourse about race (if it had been presented in a neutral or empathetic way), much of what happened instead was knee-jerk reactionism stoked by a controversy narrative.

Rachel Doležal: If I’d had the choice, I would have waited to share my story until much later in life. But, with the world clamoring for an explanation and justification for my identity, I felt the task was prematurely thrust upon me. I wrote In Full Color not only to set the record straight about who I am but also to further the dialogue about race, encourage others to be exactly who they are, and to document my journey for my sons. While my journey could have catalyzed a thoughtful discourse about race (if it had been presented in a neutral or empathetic way), much of what happened instead was knee-jerk reactionism stoked by a controversy narrative.

Amid the shouting in 2015, people reached out to tell me their own stories, to say, “you’re not alone” and that my courage was inspirational to them in their own identity journeys. Countless others sent messages asking to hear more about my experiences, and I quickly realized I could not handle the volume of individual correspondence. This book is for those who feel empowered by—or who just want to understand—my story.

While the press was swirling with assumptions and hearsay about my life, I realized that my sons didn’t know my entire story either. I had been so focused on raising them that I hadn’t talked that much about my own journey from childhood to the present. They weren’t experts on how chapters of my life fit together, and I wanted them to know my full story and have it to refer to on their own time.

AM: In the press and in your new book, you really double down on claiming a Black identity. In the very first pages of In Full Color, for example, you write about your “identity as a Black woman.” But if you could create a longer, more complex label that more fully captured your experience or viewpoint, what might that look like?

RD: I get fatigued by the overly simplistic race labels, as if people are only one aspect of who they are at a time and not able to be simultaneously a person with a gender/race/age/class/religion/sexual orientation/nationality/disability/language. Yes, Black is the closest descriptive race or culture category that represents the essential essence of who I am, and I stand unapologetically on the “Black side” of the racially constructed Black/White divide. But, if I could choose a more complex label with my own terms, it might be “A pro-Black, Pan-African, bisexual artist, activist, and mother.”

Most people on the street would likely feel that description is more confusing than helpful, so finding where I fit amid the binary language of our current race-based society, I could say “A Black woman born to White parents,” or, if I was allowed to use a newer term (also since my parents don’t define me), I would prefer “A TransBlack woman.”All three of these more complex labels seem like conversation starters to people rather than a simple answer to the question, “So, what are you?” That’s why, when picking up bread and milk at the store, it’s much more convenient to say, “I’m Black.”

AM: Your story reminds me of James McBride’s (1996) account of his mother’s life in The Color of Water: A Black Man’s Tribute to His White Mother. As I understand it, you both grew up in rural households where strict religious observance co-existed with abusive parenting. And you both found emotional comfort in the Black people you encountered in your youth, leading you to gravitate to communities of color. Looking back, what do you see as key factors or experiences that shaped your racial identity over time?

RD: My first encounter was within myself, the resonance I felt instinctually with Black as beautiful and inspirational. I didn’t know how to articulate that this was “me” except in my drawings and playtime as a child, and from there I learned what was—and wasn’t—socially acceptable about how I felt. …[M]y identity grew by degrees, organically (albeit with some periods of setback), from childhood playtime to my teenage years caring for my Black siblings, into my college years in Jackson, Mississippi, grad school at Howard University, and post-divorce into my activism and eventual claiming of Black as my identity. It felt like a long journey home. I started far away, and it just kept calling to me until I found my way fully there. Of course, feeling like I was then evicted in a sense in 2015 was painful. But it’s still home to me.

AM: In several places, your book sounds like an Intro Soc textbook on race—for example when you describe the flaws in the traditional American belief in discrete, biologically grounded races. How were you first exposed to the notion of race as a social construct? How does it influence the way you think about your own racial identity?

RD: I first read about race as a social construct—a worldview—in graduate school. I was 24 and pregnant with my son, Franklin, at the time. My thesis committee chair gave me his mother’s book, Race in North America: Origin and Evolution of a Worldview. Reading not only that race was a social construct but that this worldview pivoted off of the oppressive colonial era was somewhat of a great awakening. I felt free, like I was no longer coerced into claiming “Whiteness” because that was the “honest” or right thing to do (out of obligation to my parents and previous social conditioning). But my sense of freedom was somewhat secret and internal, because I still didn’t feel I had permission from society to really live like I actually believed race was a social construct. So, to fit in with what other people already saw me as—my husband and family in particular—I just tucked that powerful idea in the back of my mind until I could more fully integrate it.

Once I was free from my marriage and family influences and able to live a self-determined life, I connected the idea of race as a social construct with the philosophy of leaders like Dick Gregory, who said that “White isn’t a race, it’s a state of mind.” I knew White wasn’t my state of mind, and this gave me permission to stop repressing and be exactly who I am. Other books I have read since, such as Doing Race, Fatal Invention, A Chosen Exile, and The Nature of Race, have also influenced the way I think about racial identity.

AM: You’ve been asked ad nauseam about your Black identity, but I’m curious about your relationship to Whiteness today. How does Whiteness factor into your identity now, if at all?

RD: Whiteness feels foreign to me. It was, awkwardly, how people saw me when I was a child and how some people see me now, so I have to interact with that disconnect at times. The very idea of Whiteness, upon which the worldview of race was built, established the propaganda of White as righteous, pure, and superior. I reject this worldview and am not a member of, as James Baldwin called them, “people who think they’re White.”

AM: You’ve had the very unusual—though not unique—experience of living as both Black and White in the United States. What can you tell us from the vantage point of someone who’s seen things on both sides of the deepest racial divide in the nation?

RD: I can say for sure that race is a myth. People who are told I’m White “see” that when they look at me, and people who hear I’m Black “see” that in my physicality. It’s basically a self-fulfilling prophesy. …[F]ocusing on the differences to the exclusion of seeing and empathizing with the human similarities is something that keeps people divided, not only by the color line but also by religion and other categories. I’ve seen hate, fear, and ignorance from the White side, perpetrated toward people of color, and I’ve seen fear, anger, and pain from the Black side, in connection with feelings about White people. I connect with the anger and pain toward Whites—my parents in particular and the White supremacist patriarchy in general.

When thinking about people as groups and labels, it’s easier to pre-judge and have bias. When people relate to each other as individuals instead of relating to the person as a representative of the group, I’ve seen a lot of love. As my mentor, Spencer Perkins, said, it’s helpful to “play the grace card”—to get to know a person for who they are instead of dismissing them with, “Well, you know how White folks is.”

AM: As you know, in his 2016 book Trans, sociologist Rogers Brubaker has tried to understand why your racial identity became such a hot topic in the summer of 2015. Why do you think the media and the public took so much interest in your racial identity?

RD: Media is fueled by controversy, and what greater tension is there in America than race? My story—as told by others—was presented in scandalous terms, and nearly anyone who had something negative to say about me was given a microphone. I think there was more interest in venting pain or defending personal viewpoints on the topic than there was real interest in me as a person. I think people just need to talk about race, listen to others talk about it, and work through the many misunderstandings, judgments, and feelings associated with it.

AM: Do you think there is a parallel between your racial self-identification and the gender self-identification of Caitlyn Jenner, who was heavily featured in the news at the same time as you were?

RD: Inasmuch as we were both categorized at birth as something other than what we felt—and some people will always see both of us as our birth category and nothing further—there is a parallel. I think courage and some degree of harmonizing the outer body with the inner self so people visually identify us, how we identify ourselves would be a commonality as well. There is absolutely no parallel when it comes to financial resources, which are a real factor for cushioning a nontraditional self-identity; there we part ways as super-rich versus single mom barely surviving. And there’s the difference of stigma, with gender fluidity being more widely accepted than race fluidity at this moment in history. Mainstream media didn’t shame Caitlyn in the same way I was shamed. My son, Franklin, asked me how race didn’t become fluid first, with science proving time and again it is not a biological reality. It’s a good question.

AM: What do you think of the term “transracial”?

RD: I think the former use of “transracial,” describing kids who were born with a different race label than the family they grew up in (usually via adoption) wasn’t widely known enough before 2015. So, with the spotlight on Caitlyn Jenner and then me in short succession, many people began using it to describe me, as if “transracial” was a new word and I was the front-runner of a movement. In a literal sense, I don’t like the word, because it would be like saying “transhuman” to anyone who accepts that race is fiction. And yet, if that is a term that helps people understand or is useful in creating awareness and empathy for people with a plural race identity, then I’m fine with it as a starting point. I really don’t feel like it’s up to me to decide what the word should or will mean.

AM: Your book gives readers a clear sense of what your intense bout of media scrutiny and public shaming cost you: employment, privacy, and even personal relationships. That steep price for a matter of personal identification brings to mind the work of sociologist Erving Goffman on stigma and the management of “spoiled” identities. How have you coped with the scorn, the vitriol, heaped on you?

RD: It has been rough. I’ve cried, written, created art, isolated, spent time with close friends, gone out less, and cuddled baby Langston more. I’ve tried to find ways to stay connected and available to others without making myself unnecessarily vulnerable to more attacks.

AM: Beyond close family members and friends, do you feel you’ve gotten support from any particular type of person or group of people?

RD: Black women seem to absolutely love or hate me, the same goes for many White liberals. Black men, LGBT men and women, biracial women, and millennials have been the most openly supportive in numbers, though I’ve had opposition from members of these groups as well. People who have some kind of plural or non-binary race identity have been the most likely to share their personal stories in letters and messages of support to me.

AM: For my last questions, I’d like to ask you to draw on your professional experience as a college instructor and as an activist. First of all, based on your own experience teaching—or just in talking about race with people around you—what do you think is the hardest thing for Americans to understand that you wish they would understand about race?

RD: I wish Americans understood that race is a social construct, even if we don’t want it to be. We can’t ignore history and hope it goes away, we need to move toward the painful parts—toward the part in history where people invented race for power and privilege—to heal and find our common humanity.

AM: As part of your work with the NAACP and other organizations, you have repeatedly clashed with White supremacist movements in the Northwest. Now that such groups seem to be gaining a new, wider public legitimacy, what advice do you have for countering their power and their racist and anti-Semitic messaging?

RD: Be bold, but strategic and careful, too. Travel and gather in groups when possible, so the community can protect targeted individuals. Don’t ignore the hate, expose it and oppose it with love and practical actions of support for those affected. This is not the time to pick at each other over trivial issues while people’s lives—and our children’s futures—are being threatened.

AM: What issues relating to race do you think will be most important under Donald Trump? What would you like to see racial-justice activists doing?

RD: What issues relating to race are not going to be critical under a Donald Trump presidency? Things seem a bit unpredictable in just when and how and what will happen, but I feel certain that Trump’s presidency will highlight race, power, and privilege at every turn. I think we might see increasing racial injustice in police brutality, education, healthcare, criminal justice, economic opportunity, and political power under Trump.

I am encouraged by the ongoing protests, free legal aid and other types of support activists are giving to those who are most intensely affected by Trump’s executive orders and policies. I think it would be helpful if there was a focus on daily or weekly action plans and a way to streamline and connect people in the movement to achieve timely, thorough, and effective activity. It is easier to get people to show up for public events than to show up for the hard grind of sacrificing time, energy, and resources to the cause on a daily basis. But, with some vision and organization—and maybe some awesome activism apps—it will be possible to keep people engaged to the point of making an impact. If the movement is too slow, people will lose interest and the results will be dissipated. If protests are the main focus, people can feel like nothing else is happening and lose interest. It’s all about vision, organization, momentum, timing, and balance.

Ann Morning is in the sociology department at New York University. She is the author of The Nature of Race: How Scientists Think and Teach about Human Difference. She has also written an article in the Huffington Post about Rachel Doležal titled, “It’s impossible to lie about your race.“

Comments 6

Christian Hullett

March 28, 2017I still want Rachel to Marry me..... Please

Samuel N Collins

March 28, 2017I am glad that you have almost survived the so much trouble heaped upon you, and are able to come up and tell your own story, in your own words. Hopefully, the fluidity of identy issues, perhaps with your book now out-- might help share light or add new insight to Race Debate, Identity Crisis, and the role the element of choice can take in this. Whether a person is more to be identifed by how they feel or not.... Or the decision should be left entirely with the society.

Thanks for your book.

A Protection of ‘Transracial’ Identification Roils Philosophy World | Tech News Base

May 19, 2017[…] topic, or to contrast the reaction to Rachel Dolezal, the white former N.A.A.C.P. official whose claims to be black drew widespread ridicule and outrage, with the extra accepting therapy of Caitlyn Jenner, who got […]

A Defense of ‘Transracial’ Identity Roils Philosophy World | Newsrust.com

May 19, 2017[…] subject, or to contrast the reaction to Rachel Dolezal, the white former N.A.A.C.P. official whose claims to be black drew widespread ridicule and outrage, with the more accepting treatment of Caitlyn Jenner, who came […]

A Defense of 'Transracial' Identity Roils Philosophy World – New York Times |

May 20, 2017[…] subject, or to contrast the reaction to Rachel Dolezal, the white former N.A.A.C.P. official whose claims to be black drew widespread ridicule and outrage, with the more accepting treatment of Caitlyn Jenner, who came […]

AD Powell

May 24, 2017It’s Not Rachel Dolezal Who’s “Crazy”But the Ridiculous, Racist and Contradictory Definitions of “African American”

https://medium.com/@mischling2nd/its-not-rachel-dolezal-who-s-crazy-but-the-ridiculous-racist-and-contradictory-definitions-of-7a1da0a404f0