Image by fernando zhiminaicela from Pixabay

Structural Shocks and Extreme Exposures

In the United States, nearly all states have issued stay-at-home orders. Most people’s lives are legally and structurally confined to their neighborhoods and the resources in those neighborhoods. This means that structural inequality has the potential to be exacerbated rather than reduced.Let’s take two neighborhood profiles. On one hand, people in well-resourced neighborhoods with stocked grocery stores, spacious yards, and telework may largely live their days typing on laptops, accidently displaying their video on Zoom meetings, and exercising on their new Peloton bikes. On the other hand, people in low-income neighborhoods are stuck with limited produce and food options, a reduced public transportation schedule that further exposes them to risks of contracting the coronavirus, and “essential” work with low wages that has not kept pace with inflation and often leads them to serve those living in the well-resourced neighborhood.

The articles in this wave of our COVID-19 special online issue address shocks to social institutions that lead to extreme outcomes. Branch documents how the coronavirus may lead to over policing and a lasting legacy that formalized a surveillance state. Lewis-McCoy and Pothen address how local geographies matter. Lewis-McCoy gives us insights into the lives of people in New Rochelle, New York (considered ground zero of the COVID-19 outbreak in the United States). Pothen discusses how social networks matter during unstable times. Accordingly, it is even more important for scientists to be trusted.

Eyal discusses why the COVID-19 pandemic may be a make or break moment for the science community. He argues it is critically important for academics and scientists to reestablish themselves with the public as a trusted source during an era of perceived “fake news.”

The final three pieces in this issue address how families are being impacted by the coronavirus. Gengler discusses how families simply are not structurally prepared to live in a moment of crisis, while Balboa highlights the strength of family ties. Carpenter ends by discussing sex and the role the coronavirus may have on romantic and sexual relationships.

We hope the articles being released in this special online issue are useful for providing more in-depth analysis beyond headlines and White House meetings where the president discusses TV ratings. People are dying, healthcare providers and frontline workers are trying to preserve their physical, mental, and emotional health, and families are struggling. Social context matters in moments like these for people to put what is occurring on a micro-level in a broader structural context. We believe these articles help to provide this balance.

– Rashawn Ray and Fabio Rojas

- ”The Lasting Impacts of Policing Coronavirus” by Michael Branch

- ”Geographies of Crisis: New Rochelle and the Nation’s Ground Zero” by R. L’Heureux Lewis-McCoy

- “COVID-19, Containment, and Social Networks in Atlanta” by John Pothen

- ”COVID-19 is a Make or Break Moment for U.S. Experts” by Gil Eyal

- “Families are not Structurally Prepared for COVID-19” by Amanda M. Gengler

- “The Strength of Family Ties and COVID-19” by Nicoletta Balbo, Francesco C. Billari, and Alessia Melegaro

- “Sex During Coronavirus” by Laura M. Carpenter

The Lasting Impacts of Policing Coronavirus by Michael Branch

As the novel coronavirus continues to spread across the world, we must give careful attention to how this epidemic has the potential to permanently alter police practices. Responses to the coronavirus have required numerous institutions to make significant changes; law enforcement and policing are not exempt. As policing adapts to the impact of the virus in the coming weeks and months, we will see heightened levels and new forms of security and surveillance in our lives. A complementary danger here is that the epidemic provides an opportunity for police to continue a project of pacification in which police power and the state’s monopoly on violence are obscured by the presentation of police as ‘Officer Friendly.’ Between increased levels of surveillance, law enforcement becoming more actively involved in policing health and sickness, and the pacifying nature of public police responses, the impact of the coronavirus on policing has the possibility to result in the state and police being wound more tightly together in the pursuit of social order.

New police practices and behaviors are emerging in response to the coronavirus epidemic. The new practices demonstrate an increase in surveillance technologies and extension of police power into controlling everyday life. California police departments have announced plans to use drones equipped with cameras and speakers to patrol and enforce lockdowns. Other law enforcement agencies in the US have begun setting up their own drone programs to help with policing lockdowns and quarantines. Police have also gained increased powers over controlling space in response to the coronavirus. Law enforcement officers in New Jersey recently broke up two weddings, as gatherings of more than 50 people were prohibited. Police in different places have been given powers to detain those who are suspected to be sick, making sure they stay in their homes, controlling space. As a result of the coronavirus, it is possible we will see police rely more on surveillance technologies and continue to have expanded powers given under the veil of protecting public health.

Though laws vary by region, police will come to play a bigger role in policing health and sickness as their powers expand to include more forms of biosecurity. Social media posts from police departments across the United States are asking residents to disclose possible illness, regardless of positive tests, to help protect officers and keep them safe. The United Kingdom government has given police emergency powers to detain people who are suspected of having the coronavirus and issues fines for refusing tests. Operating under the guise of promoting and protecting public health, the police response to the coronavirus will result in officers having greater access to personal medical information, while also criminalizing and stigmatizing sickness. Though currently temporary, this legislation could be renewed and the scope of policing could be permanently extended to include biosecurity and policing boundaries of health and sickness.

Outside of explicit practices and actions, another worrying aspect of the police response to the coronavirus is the project of pacification through which police are rendered as ‘Officer Friendly.’ The presentation of police as ‘Officer Friendly’ is a tool to disrupt criticisms of policing, obscure the relationship between police power and the state’s monopoly on physical violence, and teach people to accept police power in their lives. Numerous police departments have shared social media posts asking people to stop committing crimes. In a Facebook post, the Kenosha Police Department in Wisconsin announced the “decision… to cancel all crime.” The Puyallup Police Department in Washington advised residents that they would let criminals know when they would be able to “resume… normal criminal behavior.” These humorous posts, in which police jokingly call for criminals to stop committing crime, are shared frequently on these social media platforms. Though seemingly positive, the continued social media presence of police as funny and as relatable will only contribute to the understanding of police as ‘Officer Friendly,’ humanizing violent authority, making it more difficult to call attention to the role of police in the normalization of the state’s monopoly on physical violence.

There was a possibility for this to be a moment in which we could have reduced our reliance on police to manage social problems. Police departments across the US have announced that they will not respond to non-urgent calls – a chance to rely less on police. But instead, while other social programs emerge, we will develop a stronger foundation for relying on police, fortifying their role in maintaining social order and increasing the reach of police power. As a result, the impacts of the coronavirus epidemic could reinforce the role of police as agents of state authority. Though police might claim they are operating under the guise of preventative care, acting in our best interest, the coming months will only strengthen the ties between state and police. Increased social media presence will also make it more difficult to call attention to those ties and the strengthening of the police role and their practices. Though this is an unprecedented moment, we must be vigilant and wary of police finding ways to expand their power and shield themselves from criticism.

Michael Branch is a Doctoral Candidate in Sociology at Syracuse University. Branch studies policing, criminal justice, and police socialization. His work is focused on police academies, the impact of police training on police behavior, and issues that emerge in rural policing.

Geographies of Crisis: New Rochelle and the Nation’s Ground Zero by R. L’Heureux Lewis-McCoy

On Thursday, February 27th, a New Rochellean, Larry Garbuz fell ill. On the 1st of March he was diagnosed with Coronavirus. Prior to showing signs, he travelled around New Rochelle and the New York City area. His daily 40-minute commute on the Metro North rail is familiar to thousands daily who trade the quiets of suburbia for the bustle of the city. Garbuz also spent time in his local community of faith attending services at his synagogue, Temple Young Israel, which became a hot bed of infection. In going about his weekly regimen, he spent time visiting friends and family in the North End of New Rochelle and other sections of Westchester. He potentially infected a number of people in close ties to his life, but there are important sociological lessons to be drawn from this.

The first set of community infections exist in New Rochelle on top of a geography that is deeply stratified by race, class, and faith. When the decision was made to create a containment zone in New Rochelle the entire city was not contained, a 1-mile area was. This kind of intervention acknowledges spatial realities but also falsely relies on non-porous social relationships. What is the line between acknowledging segregation and banking on it to contain a pandemic?

On Friday February 28th, my research assistant and I filed into a local Boys and Girls Club in New Rochelle, New York to watch a play about school desegregation and the leveling of a Black community school. Just three days later I logged into twitter and saw “New Rochelle” trending. Having spent the better part of three years in and out of the small bedroom community I thought something happened with the recently hired and embattled superintendent or another avoidable accident as the city rapidly redevelops. Not this time, instead I found out that New Rochelle was “ground zero” in the spread of Coronavirus in New York and a containment zone had been declared. At the time of announcement New Rochelle accounted for 108 of the state’s 173 cases.

When the containment zone map was released, I immediately looked to see if I had been in the area when I viewed the community play days prior. After all, I was in a gym with nearly 200 hundred people. I scanned the map and realized I had just missed the containment area by a mile or so. A sense of relief washed over me, but soon that confidence eroded as I recalled I’d taken two meetings that same day with informants in two coffee shops within the containment zone and multiple informants’ children attended school in the containment zone. A place like New Rochelle, for many outsiders, comports to a neat portrait of suburbia: tree lined, an abundance of single-family homes, wealthy and White, but the reality is that many lives intersect in 13 square miles.

Just to the south of the containment zone a significant and historical Black community resides along Lincoln Avenue. The Lincoln corridor was the site of the first school desegregation case waged in the north following Brown v. Board which earned it the title of “The Little Rock of the North.” The city’s majority White leadership decided to shutter the school in the Black part of town in an attempt to “desegregate”, an all too familiar tale for those who study school desegregation. As I sat in the gym the day before Larry Garbuz landed in the hospital, I heard the actors, local community members, lament that Lincoln School had been demolished and the bustling business corridor subsequently shuttered, highways had been constructed and as one line of the play characterized it, “it was like the community’s lights went out overnight.” For Black and Brown residents, who also tend to have lower incomes than the average White residents, the images of New Rochelle as racially integrated and lily White misrepresent their experiences. Their experiences with poverty, racial profiling, poor working conditions, etc., often receive less than a footnote in most trope-based accounts of the city.

When the New York Times’ “The Daily” podcast recently completed an episode on New Rochelle’s efforts to curb Coronavirus they reported from the Lincoln Corridor, the historic Black community outside of the containment zone. The National Guard’s primary functions are to clean and to deliver food to those who have been impacted by the pandemic, whereas they typically respond to natural disasters. In the Lincoln corridor, the food deliveries are helpful, not simply because of Coronavirus, but because in that area of town more than 15% of families fall below the poverty line whereas just up the road in the containment zone less than 1% of families do. The more acute poverty and relative deprivation of poorer families in the suburbs under considers how a pandemic in one section of town may shutter well to do businesses, but it may also chill and limit access to food, work, and other necessities outside of its confines.

For the past few weeks, I have not been in New Rochelle. I made a decision to stop field visits, one that was echoed by my university this week which suspended all Human Subjects face-to-face research, but I’ve continued to check in with informants in New Rochelle. Some I’ve come to call friends and loved ones and hearing from them and watching the public health response raises more questions for me than answers. As media describes the posh life of New Rochelle suburbanites, I wonder: have they seen the Black, Brown, and low-income community-driven GoFundMe sites that have popped up to assist with emergency food pantries? As the nation’s news boasted the drive thru Coronavirus testing center, I think about the many informants who I talked to who don’t have cars, who travel via sparse bus routes or car services to get their needs met. How would they be tested? I think about the many working class and poor families, both documented and undocumented, who didn’t have the option to telecommute and had the businesses that they work at shuttered and thusly their sources of income stopped. How will they make ends meet to survive? I think about the many who travel to other areas in Westchester and New York City not just to work but to get their needs met medically and socially. In crisscrossing in and out of the containment zone, what supports will there be if their love ones’ health is compromised? I wonder as we work to respond to the pandemic how the response to the pandemic both simultaneously ignores the fault lines that lie beneath, while using them as a basis for pathological intervention.

R. L’Heureux Lewis-McCoy is an Associate Professor of Sociology at New York University. His central line of research concentrates on educational inequality, focusing on the intersecting roles of race, class, and place.

COVID-19, Containment, and Social Networks in Atlanta by John Pothen

Many of us have heard about social networks and their role in spreading disease. But what if the opposite is also true? What if social networks can help contain the spread as well?

Let me start with social networks and contagion. Nicholas Christakis and James Fowler, in their book Connected, wrote about how the shape and structure of teens’ sexual networks dramatically affected the risk of spreading sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Similar research has shown that racial segregation in America leads to racial disparities in the rates of STIs and that studying patterns of international flights can help us predict how the flu will spread in a given year.

These examples demonstrate that social contacts between individuals fit into a larger, unseen networks that often aid the spread of pathogens. Indeed, one of the earliest known forms of network analysis was used for exactly this purpose when John Snow studied the Broad Street Cholera Outbreak of 1854. Snow tracked cases of cholera from person to person and across the timeline of the outbreak to find a contaminated water pump that started it all.

Today, social networks are at the heart of the international response to the COVID-19 pandemic. At present, I am one of millions of Americans staying home in order to practice “social distancing” and “flatten the curve” so that our healthcare system does not become even more overwhelmed. The research I’ve mentioned so far would suggest that limiting our direct contact (i.e. not participating in social networks) is critical for combating disease.

However, my own research suggests that social network participation has an important role in containing the virus. For the past six years, I’ve been partnering with a neighborhood in southwest Atlanta (I’ll call it, “Phoenix Garden”) to study the social networks of residents aged 65 and up. The neighborhood organization and I have been using these data to guide programming in support of older residents as they continue to live in the community.

As COVID-19 spreads throughout the US, Phoenix Garden’s older residents are among those with the highest risk for severe disease, and we’re mobilizing the neighborhood to support them. We solicited volunteers from every street, placed flyers on porches with information about how to stay safe, and paired older residents with lower-risk neighbors who are calling daily and running errands so they can stay home. Using our knowledge conversation networks (i.e. which neighbors routinely chatted casually outside their homes), we’re countering misinformation and making sure that older residents have someone nearby who’s ready to help when they need it. Best of all, we encouraged residents to enact social distancing early on, before federal and local guidelines were issued, and we hope that may end up saving lives.

Of course, these efforts must be conducted carefully to avoid spreading the virus. Volunteers have to be up to date on hand hygiene, how much space is needed to avoid droplet transmission, and how to do their work without dramatically increasing the risk of bringing the virus into their own homes. We’re working hard on this and, so far, the precautions seems to be working.

Without the social networks of Phoenix Garden, these efforts just wouldn’t work. For instance, without knowing who talks to whom regularly, we wouldn’t have been able to collect all the phone numbers of older adults in the neighborhood. We also wouldn’t be able to facilitate or track neighbors helping each other, and would instead face the challenge of building trust across phone lines – a heavy lift during uncertain times. Without these networks, we wouldn’t have the human power needed to check in on a daily basis and find out how all the older residents are doing each day, what supplies they might need, and who is showing signs of COVID-19 infection.

Beyond this, our work suggests that the COVID-19 pandemic has actually strengthened neighborhood social networks. Phoenix Garden is a gentrifying neighborhood, and our research up till now had shown that relationships between newer residents and longer-tenured residents tended to be limited to brief hellos and small talk in the street. While meaningful, these types of relationships tend to have little impact on preventing displacement or mitigating conflicts associated with gentrification. However, gentrifiers and long-term residents now face a shared challenge, and these relationships comprise the social infrastructure needed to meet it. Already we have reports that working together to prevent the spread of the novel coronavirus has led to deeper relationships as well as the formation of new ones between neighbors who previously didn’t talk.

The mobilization and teamwork in Phoenix Garden does not need to be unique or even unusual. Emile Durkheim’s foundational work on suicide highlights the importance of the social support and social control found within interpersonal networks. As our world grapples with the coronavirus, it will be easy to fear each other, and it will be easy for us to feel isolated and alone. With a little creativity, however, we can draw on our social networks to provide control by reinforcing new social norms (e.g. social distancing, staying connected digitally) and to provide support by making it easier to help neighbors in need and lift each other up.

We don’t need to isolate ourselves in every sense of word during this pandemic. We’re not alone. Social science shows us that we still have the potential to help each other in powerful ways. We’re in this together, and, by working together, we will survive this.

The data discussed in this article will be publicly accessible (with redactions to maintain privacy and confidentiality) as it is published in scholarly journals in the next few years.

John Pothen is a Doctoral Student at Emory University where they research structural marginalization, community, and social change in Atlanta.

COVID-19 is a Make or Break Moment for U.S. Experts by Gil Eyal

On February 25, Nancy Messonnier, Director of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases told reporters that the question no longer is if the Coronavirus epidemic will spread to the US, but “It’s more of a question of exactly when this will happen.” Soon after, the Washington Post reported a whistleblower complaint that US personnel interacting with quarantined evacuees lacked proper training and protective gear. In the following days, As the epidemic spread in the US, it also became evident that the CDC botched the development and distribution of a test for Coronavirus. And all along, viewers of White House press conferences have been treated to a new spectacle, repeated almost every night: The President and the nation’s foremost public health expert, Anthony Fauci, the longtime Director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, sparring and contradicting each other. It has become clear that the Covid-19 epidemic is not only a global disaster, a collective and personal ordeal. It is also a make or break moment for the nation’s phalanx of public health experts. After years of declining levels of trust in experts, this could be one more heavy nail in their coffin or the tipping point from which will begin a restoration of the public’s trust in experts and expertise.

It is no secret that the Trump Administration distrusted experts from day one. The Federal Agencies where they work were gutted and muzzled. Many experts were sidelined or replaced by lobbyists and cronies. Inexcusably, the National Security Council’s Directorate for Global Health Security and Biodefense, entrusted with monitoring and providing early warning about emerging new pathogens, was disbanded by the Administration. None of this was surprising. I have studied the politics of expertise for over two decades and in multiple national contexts. Invariably, Populists do not like experts. They call them “elitists” and “globalists” and imply that they cannot be trusted. The irony of this moment is that the legitimacy of politicians now depends on the professionalism and technical competence of the very experts they denounced.

Yet, the problems that beset expertise are deeper and predate the Trump Administration. Surveys show that trust in the FDA, for example, declined from 80% in the 1970s to 36% in 2006. The EPA, OSHA and the CDC do not fare much better. Many people, including leading politicians from both sides of the aisle, reject or doubt the assessments of experts, even when they are supported by solid scientific consensus, regarding climate change, environmental pollution, GMOs, mammograms or vaccines. There is a systemic crisis of mistrust in experts. It can be traced to the combination and interaction between two factors: first, experts are called upon to provide advice on matters that are politically contested and create winners and losers.

Determining which illnesses count as industrial accidents, for example, may provide relief to one group of workers and deny it to others; while putting new financial burdens on one group of employers, and protecting the bottom line of others. Second, unlike the exploratory nature of basic scientific research, regulatory science is tasked with formulating binding rules like a vaccination schedule or “acceptable levels” of a pollutant. These rules are formulated by expert committees that take into account the state of scientific knowledge at a given moment, but they also take into account other considerations such as cost, timing and coverage. For example, the vaccination schedule arrived at by the experts combines many shots together to reduce the cost of multiple doctor visits and thereby reduce the burden on poor parents. Yet, as the state of the scientific art changes, the rules can quickly become obsolete or manifestly imprecise (e.g. the recommendations when and how often should women receive mammograms, or men be tested for prostate cancer, have swung wildly over the years). In public perception, the combination of these two factors – decisions that advantage some groups and disadvantage others, which periodically become obsolete and are replaced by new rules – can appear arbitrary, ill-informed and untrustworthy. It can appear as if life and death decisions, rules that decided winners and losers, were taken on the basis of arbitrary cut-offs. Experts can appear bungling and incompetent, or worse, corrupt and callous.

A crisis, however, does not mean the “death” of expertise. To paraphrase Winston Churchill, “expertise may be the worst form of reaching decisions, apart from all the others that have been tried.” Whatever problems beset expertise; the alternatives are worse. In the US, at least, regulatory decisions must demonstrate that they were taken in a reasoned, rational manner, and it is impossible to do so without showing that one has taken into account empirical evidence and expert judgment.

An epidemic, however, throws this crisis, the push and pull of contradictory forces, into stark relief. As a result, it can further undermine trust in experts. As more than 10 million Americans filed for unemployment, it is hardly necessary to point out that expert advice creates winners and losers. But the other aspect of the crisis is also on full display. Take as an example the widely reported case of the Washington State patient who was not given a diagnostic test for several days because according to Federal rules, she was not considered high risk (she did not travel back from Wuhan). As a result, precious time was lost to detect and prevent community spread. The rules have changed since then and today she would have been given the test. Before we denounce the rigidity of the rules, we should recognize that this is exactly how decisions should be taken during an epidemic. Errors and mistakes are unavoidable. An epidemic requires allocating scarce resources on the basis of expert assessments of relative risk. If a diagnostic test was given to any coughing, feverish patient that showed up in the emergency room, we would soon have found ourselves with no test kits at all and with no defenses against the epidemic. This means, however, that even when experts are making reasoned decisions based on the best available knowledge, even as they impose on themselves uniform decision rules to avoid subjectivity and partiality, inescapably they will sometimes be wrong and their misjudgments will become public spectacle, further undermining trust. And yet, the alternatives are worse. This is why the crisis of expertise is systemic.

An epidemic, moreover, brings the crisis to a make or break moment. If there is one lesson that we can learn from what happened in China, it is that the response to an epidemic becomes part of the very dynamic of the epidemic itself (witness the much higher death rate at quarantined Wuhan). This is doubly true when it comes to trust. How an epidemic develops depends crucially on people’s trust in public health authorities. You can do all the right things, but if people don’t trust you, they will stockpile face masks and fail to self-quarantine themselves. US public health experts are entering their make or break moment doubly handicapped. First, because the systemic crisis of mistrust in expertise that I have described has already taken a heavy toll on their credibility over the years. Second, because mistrust has an infectious quality (no pun intended). If political institutions are mistrusted, this can spread to the experts as well. Fauci and Trump may spar, but they also need one another (Pierre Bourdieu would have called this “collusion in conflict”) because when one is mistrusted, it may tarnish the credibility of the other.

At the same time, an epidemic may also be a moment when people are predisposed to change their attitude and trust the experts. An epidemic is a cultural frame. It foregrounds, trains attention on what in “normal” times is pushed to the background, namely our utter dependence on far flung and complex expert systems, on the experts who run them, and on the complex calculations that underlie their advice. It is a moment of emergency when we all listen closely to the experts and hope that they know what they are doing. Despite the spectacle of incompetence at the highest levels of the political echelon, it is also evident that there are deep reserves of professionalism, integrity and competence among the ranks of American public health experts, medical administrators and civil servants. It is their make and break moment now, and we should all be rooting for them.

Gil Eyal is Professor of sociology at Columbia University. His book, The Crisis of Expertise, was published by Polity Press in 2019.

Families are not Structurally Prepared for COVID-19 by Amanda M. Gengler

The novel coronavirus that causes COVID19 may not care if we are rich or poor, celebrities, teachers, or warehouse workers. But what happens after we get sick is another story.

In my previous research with families caring for children with life threatening and sometimes rare conditions, I found that even parents who ultimately accessed care for their children at an elite university research hospital were far from equally equipped to navigate the road ahead. As a result, they turned to very different coping and decision-making strategies as they slogged through the treatment, recovery, and sometimes—devastatingly—the death and dying process. As a result, they had very unequal experiences seeking help, coping with the experience of illness and uncertainty, and carrying the weight of grief.

Though young children thankfully do not seem to become severely ill from this virus, the experience of those who may become caregivers for a loved one of any age who has or may become critically ill with COVID 19 will likely mirror the one I observed in my study. Some patients and caregivers will be able to savvily communicate with healthcare providers. They may even do so through online portals they are already set up with and comfortable using. They are likely to have friends, or friends-of-friends, who are medical professionals. These connections may provide invaluable medical advice and guidance, help them interpret symptom severity, call in prescriptions, or otherwise pull strings so they can leap over the bureaucratic hoops they would otherwise have to jump through. Celebrities who have been able to get tested for the virus while tests are in short supply are one example of this. Others may not feel able, or know that they can, do much more than sit through a long emergency room wait to get help from a provider they have no existing relationship with.

Some households will be well-equipped with electronic thermometers, over-the-counter medicines, hand sanitizer, and household disinfectants. Others will not have these basics available to them and may therefore encounter frustration from over-burdened, highly stressed healthcare providers who want to help, but expect patients to be able to manage some elements of basic medical care and surveillance at home.

And some families will have well-stocked fridges, freezers, and pantries filled with comfort foods like chicken soup or ice cream, giving them a tangible way to provide some small bit of relief and succor to those in their home whose suffering—even with more mild cases of the illness—they desperately want to alleviate. Others, especially those who faced food insecurity before the pandemic and its accompanying economic disruptions, will have no cushion to fall back on and lack these basic “home remedies” as the pandemic goes on. This can leave caregivers feeling even more helpless with little to offer as they attempt to provide comfort and “TLC” (tender loving care) as they witness an ill loved ones’ pain.

These and other resources that help us navigate the healthcare system or protect and manage our health are components of what Janet Shim calls cultural health capital, and they can help people garner what I call “microadvantages” throughout the course of illness and treatment. While beneficial in all kinds of health-related situations, microadvantages can be especially meaningful when confronting an acute and alarming medical crisis. In these harrowing situations, these seemingly small advantages can add up to a smoother, or conversely, much rockier, experience. They can go a long way towards easing the physical discomfort those who are sick must endure, and without them, an already harrowing crisis may feel even more distressing and overwhelming.

A microadvantage can be as simple as having a caregiver who feels empowered to speak up and request an extra blanket, ice chips, or a medication adjustment in the often busy and chaotic hospital setting. Whether patient and caregiver self-reports of symptoms or side effects are taken seriously and acted upon quickly by providers, or one is able to comfortably administer medications at home when needed, can also make a real difference in a patient’s illness trajectory. Beyond the tangible physical benefits that may result, a caregiver’s ability to feel efficacious—in other words, that they’ve done something to directly alleviate their loved one’s suffering—can lessen the emotional burden they bear. This is perhaps rarely more important than when patients die, and caregivers are left wondering if they, or the institution of “medicine” overall, did everything possible to save them, or at least deliver the absolute best care available.

It is, in fact, in these end-of-life cases that microadvantages may be most deeply felt.

This is where COVID19, as experienced during this global pandemic, is even more profoundly cruel. As hospitals bar visitors to contain spread, even as patients may be dying, families will be unable to provide patients with the love and care that can help everyone meet emotional goals even when life-saving goals become unattainable. Families may also be forced to consider “virtual funerals,” or to grieve in solitude while in quarantine themselves. Within a culture that already struggles to incorporate death and dying into the fabric of life, it will be even harder for people to obtain needed social, emotional, and material support in these profound moments.

As families across the globe continue caring for loved ones with serious cases of COVID19, some will be more firmly anchored as they cope with the illness. Paying attention to how inequalities play out in seemingly small, everyday ways even within or secondary to the context of larger, more fundamental inequalities in access to healthcare, is important if we are to understand where families are left at the end of this road. These are deeply traumatic experiences. They will stay with the families who endure them for the rest of their lives. It is easy to underestimate how “huge” a few microadvantages along the way can be. It is vital that we do whatever we can to ensure as many people as possible can obtain them.

Amanda M. Gengler is an Assistant Professor of Sociology at Wake Forest University. She studies medical sociology, inequality and emotions, and is the author of “Save My Kid”: How Families of Critically Ill Children Cope, Hope, and Negotiate an Unequal Healthcare System.

The Strength of Family Ties and COVID-19 by Nicoletta Balbo, Francesco C. Billari, and Alessia Melegaro

Social contacts play a crucial role in the spread of infectious diseases, and social contacts across generations magnify their effects in the case of aging-sensitive infectious diseases, which disproportionately impact the elderly. This is the case of the COVID-19 pandemic (Li et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2020; Cereda et al., 2020). How to identify contexts and populations that are potentially more vulnerable? Social survey data on co-residential patterns and intergenerational contacts, as well as data on “social mixing patterns” by age more common in epidemiology provide support for identifying such vulnerable contexts and populations. Indeed, such data are then explicitly used in modelling the spread of infectious diseases (Mossong et al., 2008).

In what follows we document the peculiar strength of family ties in Italy (and other Southern European countries), also linked to similar, but not identical, patterns in East Asia. These patterns, together with high levels of population aging (23% of the population aged 65+ in 2018), show the peculiar vulnerability of Italy to the COVID-19 pandemic. Adopting this perspective allows us to identify other contexts and populations that might be vulnerable to aging-sensitive epidemics.

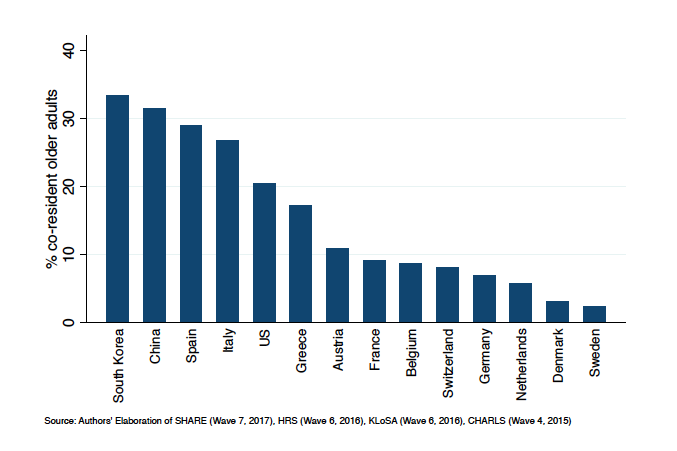

Intergenerational co-residence and contacts in social surveys

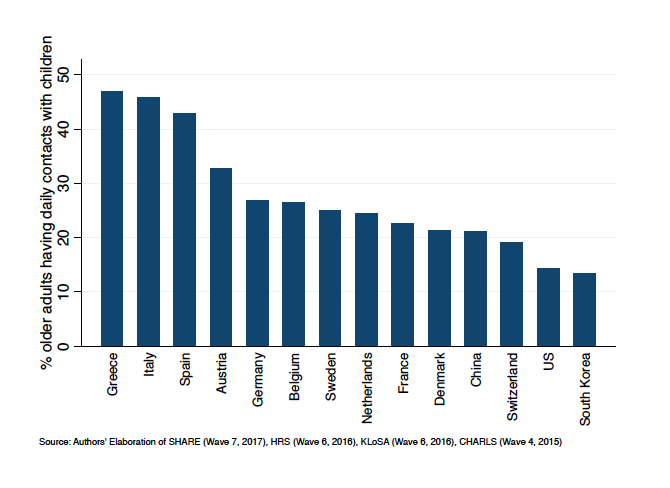

Figure 1 shows the higher prevalence of intergenerational co-residence among older adults (60 years and older) in Southern Europe and East Asia. We use data from comparative social surveys on aging, i.e. SHARE (Austria, Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland. Börsch-Supan, 2019) HRS (US. Gwenith & Lindsay, 2018), KLoSA (South Korea. Jang, 2016) and CHARLS (China. Zhao et al., 2013). The same data, in Figure 2, show that daily contacts between individuals aged 60+ and their non-co-resident children is comparatively more frequent in Southern Europe—in this case with respect to the rest of Western Europe, US, and even China and South Korea.

Source: Authors’ Elaboration of SHARE (Wave 7, 2017), HRS (Wave 6, 2016), KLoSA (Wave 6, 2016), CHARLS (Wave 4, 2015)

Source: Authors’ Elaboration of SHARE (Wave 7, 2017), HRS (Wave 6, 2016), KLoSA (Wave 6, 2016), CHARLS (Wave 4, 2015)

These contrasts in intergenerational co-residence and contacts have been well documented and have been relatively stable during the recent decades. They have been tied to the later transition to adulthood in Southern Europe, with children co-residing with their parents also up to their 30s (Billari et al., 2001). The importance of these patterns is magnified during epidemics, such as COVID-19, in which the transmission channel from younger generations to older adults is crucial in determining both the diffusion of the epidemics and its effects, including lethality. The contrasting data on daily contacts between Southern Europe and East Asia also show the higher potential vulnerability of the former group of countries due to the strength of intergenerational ties.

Social contacts surveys in epidemiology

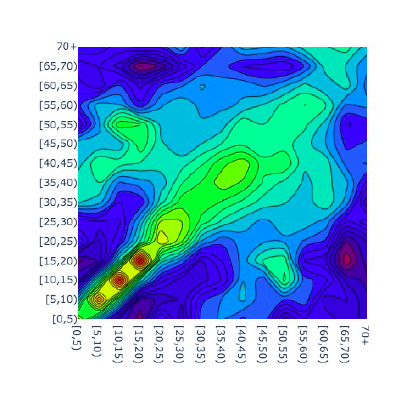

Complementary evidence comes from epidemiological studies, where social dynamics is analyzed by focusing on “social contacts”, meaning close interactions between individuals sufficient for infection spread. Social contact data are gathered directly using contact diaries (Mossong, 2008, Beraud, 2015, Leung, 2017, Zhang et al., 2019), or indirectly derived from, e.g. time use surveys (Zagheni, 2008) or through statistical models that augment these analyses (Leung, 2017, Fumanelli, 2012). Figure 3 is an example of a social contact matrix derived from a specific survey (held in 2008) for Italy, describing the intensity of daily contacts between individuals of different age groups.

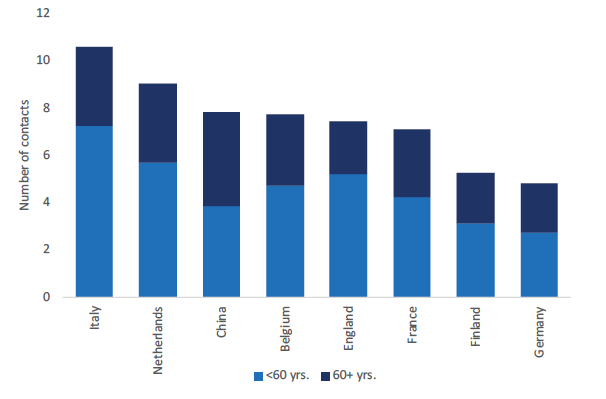

A comparative analysis of social contact data (Figure 4) shows that in Southern European countries, Italy in particular, the number of daily close interactions of older generations is relatively higher compared to other countries and that the proportion of interactions between older adults and younger individuals is also higher indicating an important channel for infectious disease transmission across generations. This is, again, showing a potential higher vulnerability to aging-sensitive epidemics.

The strength of family ties and vulnerability to aging-sensitive epidemics

The comparatively higher prevalence of intergenerational contacts in Southern Europe shows a higher vulnerability to epidemics that disproportionately affect older adults. This vulnerability is magnified for Italy, given its higher level of population aging and also higher number of social contacts for the elderly population. Radical measures towards “social isolation” have been the forced response to contain the COVID-19 pandemic. Can we learn early lessons from Italy?

First of all, Italy suggests how to identify contexts and populations that are particularly vulnerable to aging-sensitive epidemics. They are characterized by a higher share of intergenerational co-residence and contacts among generations, i.e. “strong” family ties. While culture plays a role in shaping these differences, also structural factors are relevant. For instance, in societies like the U.S. co-residence and contacts are explicit responses to lower poverty risks (Rendall & Bahchieva, 1998). While in “normal” times strong family ties are protective for older adults (Shor et al., 2013), they become risk factor during epidemics, and aging-sensitive epidemics in particular. On the other hand, strong family ties and population aging might also push policy-makers to be more sensitive on the needs and the risk of the older adult population.

Second, social contacts change as a consequence of “social isolation” measures. In the short term, while protecting vulnerable individuals (the frail and the older adult) from the epidemic, they increase the risks of loneliness and therefore mental health issues (Hossain et al., 2020). These risks must be factored in while assessing social isolation measures. In the medium-to- long term, social scientist should study whether these long-standing patterns of co-residence and intergenerational contacts will be shifted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

References

Béraud G, et al. (2015) The French Connection: The First Large Population-Based Contact Survey in France Relevant for the Spread of Infectious Diseases. PLoS One 10(7)

Billari, F. C., Philipov, D., & Baizán, P. (2001). Leaving home in Europe: The experience of cohorts born around 1960. International Journal of Population Geography, 7, 339 – 356.

Börsch-Supan, A. (2019). Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) Wave 7. Release version: 7.0.0. SHARE-ERIC. Data set. DOI: 10.6103/SHARE.w7.700

Cereda D, et al. (2020) The early phase of the COVID-19 outbreak in Lombardy, Italy. medRxiv

Fumanelli, Laura, et al. (2012). Inferring the structure of social contacts from demographic data in the analysis of infectious diseases spread. PLoS computational biology 8.9.

Gwenith G Fisher, Lindsay H Ryan, Overview of the Health and Retirement Study and Introduction to the Special Issue, Work, Aging and Retirement, Volume 4, Issue 1, January 2018, Pages 1–9, https://doi.org/10.1093/workar/wax032

Hossain, M., Sultana, A., & Purohit, N. (2020, March 13). Mental health outcomes of quarantine and isolation for infection prevention: A systematic umbrella review of the global evidence. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/dz5v2

Isengard, B., & Szydlik, M. (2012). Living apart (or) together? Coresidence of elderly parents and their adult children in Europe. Research on Aging, 34, 449– 474. DOI: 10.1177/0164027511428455

Jang SN. (2016) Korean Longitudinal Study of Ageing (KLoSA): Overview of Research Design and Contents. In: Pachana N. (eds) Encyclopedia of Geropsychology. Springer, Singapore

Leung K, et al. (2017) Social contact patterns relevant to the spread of respiratory infectious diseases in Hong Kong. Sci Rep 7(1), 1–12

Li Q, et al. (2020) Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus– infected pneumonia. New England Journal of Medicine. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316; 6

Mossong J, et al. (2008) Social Contacts and Mixing Patterns Relevant to the Spread of Infectious Diseases. PLOS Medicine 5(3): e74.

Prem, K., et al. (2017). Projecting social contact matrices in 152 countries using contact surveys and demographic data. PLoS computational biology 13.9: e1005697.

Reher, D. (1998). Family Ties in Western Europe: Persistent Contrasts. Population and Development Review, 24(2), 203-234. doi:10.2307/2807972.

Rendall, M., & Bahchieva, R. (1998). An Old-Age Security Motive for Fertility in the United States? Population and Development Review, 24(2), 293-307. doi:10.2307/2807975

Shor, Eran, David Roelfs and Tamar Yogev. 2013. “The Strength of Family Ties: A Meta- Analysis and Meta-Regression of Self-Reported Social Support and Mortality.” Social Networks 35:626-638.

Taylor, H. O., Taylor, R. J., Nguyen, A. W., & Chatters, L. M. (2016). Social isolation, depression, and psychological distress among older adults. Journal of Aging and Health, 1– 18. doi: 10.1177/0898264316673511

Yang Y, et al. (2020) Epidemiological and clinical features of the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak in China. medRxiv. 2020; Available from: https://www.medrxiv.org/ content/early/2020/02/11/2020.02.10.20021675.

Zagheni, E. et al. (2008). Using time-use data to parameterize models for the spread of close- contact infectious diseases. American journal of epidemiology 168.9: 1082-1090.

Zhao, Y., G. Yang, J. Strauss, J. Giles, P. Hu, Y. Hu, X. Lei, A. Park, J.P. Smith and Y. Wang. 2013. China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study- 2011-12 National Baseline User’s Guide. China Center for Economic Research, Peking University

Zhang, J., Klepac, P., Read, J.M., Rosello, A., Wang, X., Lai, S., Li, M., Song, Y., Wei, Q., Jiang, H., et al. (2019). Patterns of human social contact and contact with animals in Shanghai, China. Sci Rep 9(1), 1–11

Nicoletta Balbo is Assistant Professor of Sociology at Bocconi University and a Research Fellow at the DONDENA Centre for Research on Social Dynamics and Public Policy.

Francesco C. Billari is a Professor of Demography and Dean of the Faculty at Bocconi University.

Alessia Melegaro is an Associate Professor in Demography and Social Statistics at Bocconi University and a Research Fellow at the DONDENA Centre for Research on Social Dynamics.

Sex During Coronavirus by Laura M. Carpenter

There’s a joke making the rounds on the Interweb as more and more workplaces, schools, and other social institutions are asking people to sequester themselves at home in order to reduce the transmission of novel coronavirus, aka COVID-19. Q: What do you get nine months after a national quarantine? A: Maternity wards bursting full of newborns named Corona and Fauci.

The joke pivots on the assumption that adults who suddenly find themselves stuck at home with nothing much to do will eventually wind up having sex. Lots of sex. And, as everyone knows, one result of sex—a certain kind of sex, between partners of certain ages, with certain sex organs, and certain (lackadaisical) contraceptive habits—is babies.

Could this really happen? There is, in fact, some evidence of small, localized baby booms ensuing roughly nine months after major storms and electric blackouts, suggesting temporary, confinement- or boredom-inspired spikes in sexual activity. (See, for example, research by economists Richard W. Evans, Yingyao Hu, and Zhong Zhao; but also see sociologist J. Richard Udry’s classic myth-busting analysis.) But what happens if the blackout or equivalent lasts for weeks, even months, on end? What if it involves more rather than less recourse to web-connected technology? What if there’s a potentially lethal infectious disease in the mix? (Notably, COVID-19 requires far less physical contact to spread than do the infections we call sexually-transmitted.)

Suffice to say, human sexual relationships are one of myriad aspects of social life that will be affected by our recent, coronavirus-inspired regime of “social distancing.” As we all hunker down, it behooves us to ask: Will self-seclusion on a massive scale enhance or diminish people’s sex lives? Will they have more or less sex? Better or worse sex? Felicitous or potentially injurious sex? (Note that I’m focusing here on consensual sex in non-abusive relationships; how social distancing affects sexual assault and intimate partner violence merits separate attention.)

How social distancing will reshape sexual life depends, in part, on how—and especially with whom—people live. Even as we are distancing ourselves from most other humans (our weak ties), we are increasing our daily contact with the people we live with (our strongest ties). People who share a residence with their sexual partner(s) face the fewest impediments to continuing their sex lives as usual, whatever that means for them. (Scholars of asexuality like Kristina Gupta would remind us that not everyone, not even everyone with a romantic partner, is interested in sex.) Some cohabiting couples and polyamorous domestic groups may even manage to turn the next few weeks or months into a second honeymoon of sorts.

But some pitfalls and impediments exist. For one, stress ramps up some people’s sexual response while it tamps down others’ (see psychologist Emily Nagoski’s Come as You Are). This simple fact can prove particularly frustrating when sexual partners don’t share a response pattern. Familiarity presents a different pitfall. Partners have less sex the longer they are together, though why is complicated. People get bored, sure (social scientists call it habituation), but they also have lots of everyday responsibilities, which they may minimize early in relationships (see sociologist Virginia Rutter’soverview). It remains to be seen how our libidos will be affected by weeks of skipping showers and watching our partners take Zoom meetings in their sweatpants. Finding what feels like sufficient privacy and space to engage in enjoyable sexual activity may be tricky for folks who share their residence with others, especially school-age children who are now home 24/7 instead of attending school, playdates, and part-time jobs.

The circumstances of young adults sent home from residential colleges and universities is challenging territory for parents and offspring alike. Both generations are accustomed to more privacy and independence than quarantine affords. Even though residential colleges aren’t quite the factories of fornication depicted in popular media, and not every student engages in the hooking-up scene, college students are used to charting their own sexual course. Many families will need to decide whether to retain or renegotiate pre-college parietal house rules.

Things are different still for people who don’t share an abode with a sexual partner. (Living alone is on the rise in the United States and other rich countries.) Previously platonic housemates may well become friends-with-(sexual) benefits, given a felicitous combination of sexual orientations. They would do well to communicate clear expectations beforehand. (That’s good advice for all sexual relationships, in any event.)

Will people get so bored and itchy for sexual intimacy that they take untoward risks? How do you date in a pandemic? Can we harness the many lessons we’ve learned about the social side of sexually transmitted epidemics? I fervently hope so.

Some readers may be grumbling: Isn’t sexual activity a trivial concern when people are losing their jobs, their freedom of movement, even their lives? These are vitally important issues, no doubt. But the sexual effects of the pandemic are serious, too. Sex is a cherished part of many people’s lives; it makes them happy. If that’s not convincing enough, there’s also evidence that an active sex life is good for mental and physical health, relationship satisfaction, and sound sleep.

So let’s strive to sustain our sex lives, in all their glorious diversity, in ways that reward and comfort us. If you reside with your partner(s), it may be time to get creative and try “those things” you’ve always meant to. It’s also time to be patient and understanding. If you have adult kids at home, you might consider following the lead of Italian families who effectively pretend their adult children are not sexually active in the parental home. If you don’t reside with your partner, you’ve got multiple options, including phone sex (how retro!), sexting (with permission), and camming. If you don’t have a regular partner, enjoy flirting online plus any of the above, not to mention masturbation. (Heck, that’s fun for anyone.) Practice good hygiene with sex toys and take care about your privacy. In this context, safer sex means a secure Internet connection and password protection. Most of all, don’t give up on intimate pleasure and human contact in times of stress and trouble.

Laura M. Carpenter is Associate Professor of Sociology at Vanderbilt University, author of Virginity Lost: An Intimate Portrait of First Sexual Experiences, and coeditor of Sex for Life: From Virginity to Viagra, How Sexuality Changes Throughout our Lives.

Comments 12

webpage

April 16, 2020Indeed the situation is too grave all around the US and pandemic has forced everyone to stay at home, putting all future plans on hold and it is estimated the worse crisis after 1930's great depression due to World War II.There is no doubt that US is the current epi center of the outbreak and there is a very popular webpage that is sharing all updated data in accurate form.

Tehmina

April 16, 2020Well i have seen lots of informational blog regarding world war 2 and i think your blog is awesome for all the related bloggers who are always trying to improve their visitors information. There are rare blogs which i have seen regarding this topic , Thanks alot and i ll save this perfect and accurate stuff for my assignment and will publish this on my webpage for my followers.

Philip Benson

April 21, 2020It is quite a technical post but I really needed some quality content for my https://www.lakenormanhardscapes.com/ paper assignment work and your post really helped me a lot.I want you to keep uploading more quality stuff. Thanks.

johnsmith

April 28, 2020what a great and appealing article.you really did a great job.i appreciate it.in fact i am going to share this with others.keep posting

purchase Samsung s10 refurbished a reasonable price

Symons

May 5, 2020Budget-friendly host is available, you just have to look for it.Personal Hosting provide various organizing bundles and also cheap internet site .

Robert B.

May 11, 2020Sitting at home in quarantine, my wife and I began to have more sex. You touched on the topic of sex in your article, can you expand this topic? Write more about contraceptives, also I interesting the question of choosing pills for a longer erection. What is the best erection pill: Viagra, Cialis or Levitra?

distance

May 15, 2020Previous sociological research on pandemics found that “emerging diseases provoke common reactions, which are only slightly modified by national environments” (Dingwall, Hoffman & Staniland 2013: 172). Denmark is neither the first nor the only welfare state to encourage co-production in response to the threat of pandemics. It is worth noting, however, that the Danish authorities, exemplified by the Prime Minister, encourage co-production of public health in a nationalistic frame that link the practice to the enactment of ‘good citizenship’. Denmark was the first European country to close the borders, and the pandemic currently appears to reinforce an us-them rhetoric. In a fortress-like approach, Danes seek to help Danes and keep the suffering and chaos of the outer world at a distance happy wheels. The ethics and viability of this approach stand to be tested.

Jake

May 27, 2020People love talking. So, I just want to add that many gamblers from around the world already like such services as https://manhattanslots.com because their reviews gave me many opportunities.

ahnaf

July 15, 2020I have never seen this type of article before related to world war 2. you are amazing. This article helps many other to increase there information. I will like to save this and share it on my page academic cv writing services it would help me to complete my work and also beneficial for others.

Raymond

July 23, 2020Many precaution should be taken during this world disaster pandemic corona virus. But nothing could make us satisfied till we have an effective vaccine! Get Cartoon Stimulation to play your favorite online games 100 % free.

Kim ching

August 19, 2020Such a piece of important information. Keep it up. Chinese b2b platform

hanryleo

September 1, 2020great article. you always put so much information in your articles thanks for posing these amazing blogs and keep working hard. i am waiting for your next article. Give a start to your career by learning

Pay per click management professionally from our site.