Image by Geralt on Pixabay

The Global Coronavirus Epidemic: Commentary on East Asia’s Response

Contexts Magazine: Sociology for the Public issued a call for papers 10 days ago and gave authors five days to submit opinion-editorials. We received nearly 200 submissions with authors from or topics on the following countries: Australia, Austria, Bangladesh, Brazil, Canada, China, Congo, Cuba, Denmark, Ecuador, Germany, Greece, India, Ireland, Italy, Jamaica, Netherlands, Singapore, South Korea, Sweden, Taiwan, Trinidad and Tobago, Turkey, United Kingdom, Venezuela, and United States.

While some scholars commented on the Contexts website that “Sociologists should be caring of humans not using this extreme situation as [an] opportunity to expand one’s CV,” others said “It’s not about expanding one’s CV. It’s about increasing our understanding of social phenomena.” We agree with the later comment and the overwhelming number of submissions suggest that sociologists have a lot to say. And, some of us may cope through writing and feeling as though we are contributing to society by using our expertise to help humans make sense of what is occurring.

With the number of submissions we received, the editorial team had to triage them and ensure we provided each submission the same attention and evaluation. As we have through our editorship, we aimed to combine pieces by theme. We like pieces that were complementary. We also appreciated submissions that had local insights, data, and policy relevance.

Accordingly, our plan is to roll out articles over the coming weeks on topics related to Asia, healthcare, frontline exposures and critical infrastructure, policy, education, and social inequality. We ask that authors be patient as we roll them out. We will be in touch with authors as their pieces are being prepared for the website.

With this said, we start with Asia as it is considered ground zero for the global pandemic. The articles in this first wave focus on why Taiwan has such few cases despite its geographic proximity to mainline China, how Asian countries and polities deal with medical supply problems, and how families grapple with physical and social isolation. We will also feature more articles on Asia and the experiences of Asian Americans over the coming weeks. These are just the first wave.

In responding to the call, a scholar on the Contexts website stated, “Sociology has the most sophisticated theoretical insights, conceptual tools, and policy ideas. It is high time for sociologists to gather and explain the experiences of people around the world affected by this pandemic.” Contexts Magazine: Sociology for the Public provides sociologists and other social scientists, academics, and practitioners the ability to contribute in real-time when it matters instead of years later when the tide to directly impact people’s attitudes and behaviors in the moment has subsided. “‘If not us, who? If not now, when?’ We should be leading the discussion that makes this as much about the “social” as it is the biological and we should be doing it now.” We agree and we are doing it.

– Rashawn Ray and Fabio Rojas

- ”Taiwan’s State and Its Lessons for Effective Epidemic Intervention” by Ming-Cheng Lo

- ”Four Asian Polities Grapple with Medical Supply Problems: Markets and Social Power in Healthcare” by Wan-Zi Lu

- ”Social Isolation and City Shutdown as a Response to COVID-19” by Yue Qian

- “National Health Insurance, Health Policy, and Infection Control: Insights from Taiwan” by Ya-Wen Lei

“Taiwan’s State and Its Lessons for Effective Epidemic Intervention” By Ming-Cheng Lo

As the COVID-19 outbreak continues to threaten and disrupt lives across the globe, Taiwan, a small island which has long endured diplomatic isolation on the international stage, is suddenly held up as the “gold standard” for how to contain this pandemic (Smith, 2020). As of March 25th, Taiwan has only 216 confirmed cases of the new coronavirus among a population of 23 million and maintains a low community transmission rate. It has been able to achieve this level of containment with relatively moderate social distancing measures, even though the island sits off China’s coast and is linked with many Chinese cities with frequent direct flights. How Taiwan beats the odds has made headlines in the New York Times, the Washington Post, the National Public Radio, ABC News, the Guardian, among others.

A JAMA (the Journal of American Medical Association) report attributes Taiwan’s success to its proactive and comprehensive containment measures, including 124 action items, which are being coordinated by a centralized and transparent public health authority and facilitated by the island’s national healthcare infrastructures and utilizations of digitalized patient records and related big data (Wang et al. 2020). Having learned their lessons from the 2003 SARS outbreak, at the first sign of the epidemic, the Taiwanese started to test all who might have been infected and trace the contact history of each confirmed case, which has allowed for practices of effective and targeted isolation rather than citywide lockdowns or large-scale business closures.

Taiwan certainly has not declared victory over COVID-19, as the global pandemic is far from abating. But most Taiwanese are relieved that, for now, their containment efforts have paid off. This success yields some sociological lessons regarding community resilience during epidemics.

First and foremost, the Taiwanese experience illustrates that a strong and responsive state is vitally important in protecting community health. Even as the Taiwanese have leaned heavily on community networks and a civic culture that honors the rule of law during this crisis, it is state agencies that have provided the authority, coordination, scientific expertise, and massive resources needed for the containment efforts. No amount of market efficiency or NGO creativity can excuse the state from performing such duties.

The Taiwanese public is also beginning to recognize that, from a public health perspective, everyone in the community needs protection. As the epidemic rages on, activists, sociologists, and civic groups called for healthcare professionals to reach out and offer testing to the migrant workers, most from Southeast Asia, who have gone into hiding after overstaying their labor contracts. The argument that migrant workers care for Taiwanese citizens’ elderly parents and help contribute to Taiwan’s economy is a familiar one. But the emphasis that any untreated patient is a threat to all invites the public to consider how their biases towards these “outsiders within” may unravel their containment success. While a consensus is still in the making, the issue is gaining legitimacy and visibility.

Meanwhile, the Taiwanese public is also grappling with the dilemma that, given that the medical resources within the community are finite, even an inclusive community must assert boundaries. Indeed, some form of medical rationing is inevitable in all universal healthcare systems (Reich 2014), but the challenge lies in how most reasonably to delineate the boundaries of national healthcare membership. Recently, a Congressman proposed to make it more difficult for overseas Taiwanese to utilize Taiwan’s health care system. An online survey ensued in the newspaper the United Daily, with more than 80% of the respondents supporting the Congressman’s proposal or similar measures. Many commented that such measures would be necessary to ensure the sustainability of Taiwan’s national healthcare system, which is widely recognized as a cornerstone in Taiwan’s containment success.

Such debates about how to balance the inclusivity and sustainability of healthcare systems are important. But they also have the tendency to spiral into exercises of defaming the excluded. The Congressman argued that overseas Taiwanese’ medical tourism explains why the Taiwanese healthcare system is in financial trouble. He and his supporters nicknamed his proposal “Huang An Proposition,” named after an infamous retired Taiwanese singer who resides in China and often belittles Taiwan but regularly returns to Taiwan for his medical procedures. The implication that overseas Taiwanese are disloyal to Taiwan while abusing the island’s healthcare resources is of course problematic, not the least because it deflects public attention from urgent issues. Taiwan’s healthcare system is indeed under-funded – Taiwan spends 6.5% of its GDP on healthcare expenditure, about two thirds of the healthcare expenditures in most developed countries and one third of that in the United States. Fearing impacts on election outcomes, Taiwanese politicians have been avoiding the unpopular topic of raising the premiums. COVID-19 is introducing an opportunity for the public to confront this issue, but only if the populist discourse of scapegoating overseas Taiwanese does not hijack this conversation.

Taiwan’s success to date at containing COVID-19 reveals some of the structural and cultural reasons for its community resilience, including an effective national healthcare system, a strong and responsive state, a cultural shift towards protecting the marginalized, and a reckoning with the importance of delineating boundaries for an inclusive but sustainable healthcare system. Meanwhile, to the extent that even inclusive communities cannot do without boundaries, Taiwanese must resist the temptation to defame those who are outside of their community, and instead treat even “outsiders” with compassion and respect. These may also be worthy lessons for the rest of the world.

References

Reich, Adam D. 2014. “Contradictions in the Commodification of Hospital Care.” American Journal of Sociology 119(6):1576-628.

Smith, Nicola. 2020. “Taiwan sets gold standard on epidemic response to keep infection rates low.” The Telegraph, March 6, 2020.

Wang CJ, Ng CY, Brook RH. 2020. “Response to COVID-19 in Taiwan: Big Data Analytics, New Technology, and Proactive Testing.” JAMA. Published online March 03, 2020.

Ming-Cheng Lo is a Professor of Sociology at University of California-Davis, and is the author of Doctors within Borders: Profession, Ethnicity, and Modernity in Colonial Taiwan.

Four Asian Polities Grapple with Medical Supply Problems: Markets and Social Power in Healthcare by Wan-Zi Lu

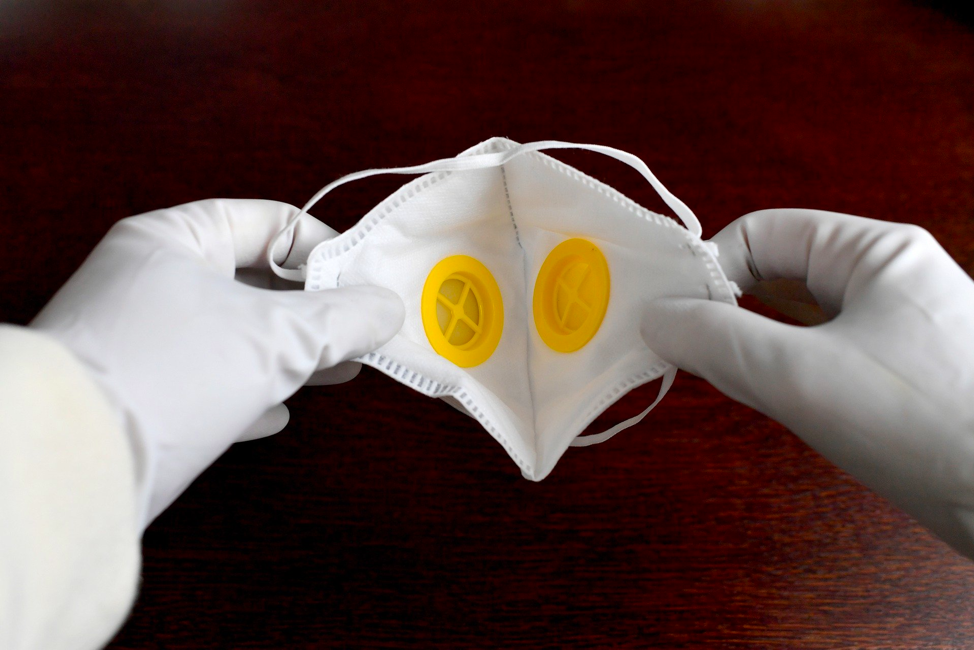

Amid the coronavirus pandemic, face masks have become one of the most needed commodities as they are essential for the safety of hospital workers and patients. But supplies remain insufficient, especially as medical demands surge and the panicked public are increasingly consuming masks for personal use even though experts advise that masks should only be worn by those who are ill or are vulnerable. To contain the panic over face masks shortages and to protect the supplies of face masks for hospital workers, governments in East Asia have adopted a wide array of policies—some of which directly intervene in the markets of face masks. The variety of policies offers an opportunity to examine how political legitimacy claimed during disruptive times may redefine normality.

Four East Asian polities that have been noted for their efforts in containing the outbreaks represent a set of possible approaches to providing face masks to those in need and easing the social panic by regulating distributions (Table 1). In Hong Kong, the government decided that any controls “could be counterproductive.” Subsequently, the market mechanism operates in its full force and the prices of face masks have skyrocketed. Singapore’s policy follows an existing regulatory framework: With a Price Control Act in place since the past century, retailers have to submit reports explaining any price increase to the government. If the government-assigned price controllers find the explanations unsatisfying, these officers can interview and inspect the warehouses and retail outlets. Since the outbreak of the epidemic in late January, the government has received hundreds of complaints about the soaring prices of the masks, and price controllers have launched investigations and urged “businesses to exercise corporate social responsibility.”

While the Singaporean government applies its price-cap regulation, the South Korean government initially attempted to control the quantities instead of the prices of masks. Up until early March, the government required face masks suppliers to give an increasing portion of their supplies to authorities, and eventually banned all exports. When the tightened measures still failed to reduce the long waits to purchase face masks, the South Korean government enforced a mask name-based rationing plan that Taiwan has also implemented since early February. Shifted away from the polity’s former market system, the Taiwanese government has regulated both the price and quantity of the production and the sales of face masks. The government has controlled all supply chains—no exports are allowed—and businesses that sell face masks at different prices or outside the government contracted pharmacies risk fines. The rationing systems in South Korea and Taiwan enable every citizen to purchase two to three masks using national identification cards every week at prices higher than before the outbreaks.

The results? Hong Kong’s medical associations called attention to the limited masks available for hospital workers last month, while the general public also had difficulty obtaining masks. In Singapore, the public has waited in long lines to get masks as well, a phenomenon resulting in the government to repeat the guidelines for mask-wearing. Notably, as the Singaporean government called for businesses to show their corporate social responsibility by not profiteering, Hong Kong’s tycoons demonstrated their social responsibility by sending masks to the hospitals. Actors with political interests stepped in as well—social activists and political parties gave away face masks in their constituencies. The partisan divide has mapped onto the sources of these gifts: the pro-establishment camp got face masks from Beijing, whilst the pro-democracy camp imported masks from the States.

In the face of dire need and insufficient supplies, the distribution of face masks as either gifts or goods reveals the structures of power within each polity. In South Korea and Taiwan, masks have become one of the most visible goods through which governments (i.e., the incumbent parties in both democracies) exert and legitimize their control over personal information amid the crisis. It is also hard to judge the outcome of the rationing systems: though many people are satisfied as they at least get two to three masks weekly, the fear over the virus nonetheless prompts panic buying as everyone feels compelled to obtain some masks without thinking about whether it is necessary. Months into the policy implementations, for instance, people still line up to purchase masks in Taiwan.

Meanwhile, the strong interventions also affect retailers and suppliers as they have breached export contracts and have been encouraged to expand production to increase domestic supplies to confine to the regulations. The economic loss of these businesses is a tip of the iceberg, showing that while the policies are intended to be short-term initiatives to address an unfolding crisis, these temporary measures may nonetheless permanently reshape the market after the crisis. In addition to the socio-economic uncertainty, the face masks policies offer implications for political orders: Will the face masks become political tokens translating into votes from the grateful public in Hong Kong? And in South Korea and Taiwan, how will the governments make use of the personal data collected under the name-based rationing policies?

Table 1: Government Interventions in Face Mask Markets Across Four East Asian Polities

| The government controls the prices of face masks | |||

| No | Yes | ||

| The government allocates face masks | No | Hong Kong | Singapore |

| Yes | South Korea (until March 9th) | Taiwan (rationing masks) | |

Wan-Zi Lu is a Doctoral Candidate in Sociology at the University of Chicago. She has recently co-authored a chapter for The New Handbook of Political Sociology. Her dissertation, “Body Politics: Morals, Markets, and Mobilization of Organ Donation,” traces the regulations and practices of bodily giving in a number of East Asian polities and compares the global development using mixed methods.

Social Isolation and City Shutdown as a Response to COVID-19 by Yue Qian

As we struggle to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic, experts in North America urge people to practice social distancing to flatten the curve. Epidemiologists recommend that people minimize social contact and limit all social engagements to slow COVID-19 spread. Although social distancing measures, such as school dismissals, closing public places, and cancelling mass gatherings, are much less disruptive than locking down an entire megacity, they are still difficult to implement in the West. News outlets reported that some Americans were still crowding into bars and over six thousand runners took part in the Bath half marathon in England. Given the resistance to comparatively mild social distancing measures, could we imagine what would happen if more draconian quarantines were in place?

Wuhan, where COVID-19 originated, was the epicenter of the outbreak. As of March 15, 2020, a cumulative total of 50,003 COVID-19 cases were reported in Wuhan, accounting for over 60% of all cases in China (80,860). Wuhan is the capital city of Hubei Province and major transit hub in central China, with a population of over 11 million. The COVID-19 outbreak happened during the Chinese New Year season when typically, millions of people would move around to attend gatherings and visit relatives and friends.

In response to COVID-19, the Wuhan municipal government announced, at 2:00 am on January 23, 2020, that beginning at 10:00 am, it would cancel planes and trains leaving Wuhan and suspend public transportation within the city. On January 26, the municipal government further banned vehicle use, including private cars, in downtown areas. The New York Times reported that “the scale of China’s Wuhan shutdown is believed to be without precedent.” Research showed that this large-scale shutdown delayed epidemic growth and containedCOVID-19 spread. Indeed, on March 15, there were only 4 new cases of COVID-19 in Wuhan, falling from a peak of 13,436 new cases reported on February 12.

It is striking to observe that Wuhan shutdown took place at such short notice without provoking social unrest. This difference in public attitudes towards social distancing in the West and massive quarantine in Wuhan highlights the important influence of cultural contexts on individual decision-making during a public health emergency. Therefore, a crucial task for social scientists is to understand the sociocultural dimensions of the COVID-19 outbreak and public health measures. In a project recently funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, I propose to examine how Wuhan residents understood the purpose of the quarantine, and why and how they followed it. This project will provide evidence to inform a culturally-sensitive response to epidemics. As underscored by the World Health Organization (WHO), “incorporating cultural awareness into policy-making is critical to the development of adaptive, equitable and sustainable health care systems.”

As a public health response to COVID-19, the ongoing quarantine in Wuhan is an imposed form of social isolation. It would be extremely challenging to local residents if they were left to deal with it alone. Sociologistshave long recognized that disaster impact and recovery are shaped by structural conditions, such as social service availability, social cohesion, and commercial conditions at the community level. Likewise, during Wuhan shutdown, shequ (residential community-level governing bodies) play a key role in responding to COVID-19.

While the municipal government announces the overarching goals at different stages of the COVID-19 outbreak, resources and services are mobilized by shequ to work toward these goals. For example, on January 24, the municipal government announced that shequ should conduct comprehensive temperature screening, classify suspected cases, arrange vehicles to transfer patients to designated hospitals for diagnostic tests and treatment, and provide services to residents undergoing home isolation. To ease inconveniences during the quarantine, the municipal government recruited 6,000 taxis, with 3-5 taxis assigned to each shequ to help deliver supplies, groceries, medicine, etc., but the shequ committee had the authority to decide how to actually use the taxis and who had access to the services. Thus, shequ contexts may play a salient role in strengthening the individual’s capacity to cope with the quarantine and the outbreak.

A fruitful avenue for future research is to evaluate the various types of shequ services received by Wuhan residents, usefulness and shortcomings of shequ services, the distribution of resources within and across shequ, and the implications of shequ services for public health outcomes. At the minimum, community-oriented action seems a promising approach to the COVID-19 pandemic. As COVID-19 is spreading rapidly around the world and many countries are expanding quarantine measures, coordinated community-based services may well help local residents stay connected amid social distancing and city lockdown.

At the time of my writing, the COVID-19 outbreak has killed more than 7,000 people and infected over 180,000 people globally. As stressed by the WHO, “We must remember that these are people, not numbers.” Thousands of people in Wuhan and worldwide lost their family members, or even more tragically, whole families were infected and died from COVID-19. Millions of people in Wuhan have been under quarantine for almost two months, and they do not yet know when it will be over. The economy in Wuhan takes a huge hit: Many businesses are temporarily suspending operations or permanently closed, and many people have lost their jobs and are struggling to make ends meet. The COVID-19 outbreak is deeply embedded in real people’s lives. As this public health crisis is taking place in real cities, regions, and countries with actual sociocultural structures, recognizing the significance of local contexts is vitally important for achieving an effective response. To mitigate potential negative consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, social science research is much needed to identify approaches for supporting culturally-sensitive outbreak response efforts and post-pandemic recovery strategies.

Yue Qian is a Professor of Sociology at the University of British Columbia-Vancouver, where they research gender, family, and population. Their work recently appeared in the American Sociological Review.

National Health Insurance, Health Policy, and Infection Control: Insights from Taiwan by Ya-Wen Lei

Despite its exclusion from the World Health Organization (WHO) and its geographic proximity to China, Taiwan has been doing relatively well in responding to the COVID-19 outbreak. The country has 23 million citizens, of which 850,000 reside in China (Wang, Ng and Brook 2020). There are 216 confirmed cases at the time of this writing. Taiwan has contained the spread of COVID-19 from China quite successfully despite being faced with the challenge of continuingly containing the outbreak after COVID-19 spread widely in the world. I argue that the Taiwanese collective memory of the 2003 Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) outbreak and the country’s democratic developmental and welfare state explain Taiwan’s swift and effective response to the COVID-19 outbreak.

Between November 2002 and July 2003, an outbreak of SARS occurred in southern China. In Taiwan, the first case was reported in March 2003. The outbreak in Taiwan caused 668 probable cases with severe deterioration of pulmonary function and 181 deaths. As an effort to contain the epidemic, the lockdown of a hospital in Taipei led to severe long-term physical and mental illness among patients and healthcare workers quarantined in the hospital (Chen et al. 2005). Due to the collective memory of the tragedy, there is a consensus among Taiwanese—no matter their political orientation—about how easily an epidemic can become out of control. Since the SARS crisis, state and society actors in Taiwan have also improved governmental and societal responses to epidemics. The collective memory explains the swift reaction of the government to the COVID-19 outbreak, from border control to case identification and tracing, containment, and resource allocation (Wang, Ng and Brook 2020). Such memory also accounts for the societal support of governmental action.

Taiwan is also a classic example of the developmental state (Evans 1995). The state played a critical role in the country’s industrial transformation. Peter Evans (1995) famously argued that autonomous bureaucracy and connections between the state and business actors explain the success of late industrial transformation in several Asian countries. The legacy of Taiwan’s developmental state is reflected in the way the Taiwanese state has mitigated the shortage of masks amidst the COVID-19 outbreak. Because population density is high in Taiwan, Taiwanese rely on masks to protect themselves. Taiwanese also learned the importance of mask-wearing from their experience with SARS. There has been a shortage of masks in Taiwan after the COVID-19 outbreak, as Taiwan depends on imports from China. To address the shortage, the Taiwanese developmental state first prohibited the export of masks. Furthermore, it has mobilized manufacturers and coordinated companies and technicians to set up 92 production lines and, thereby, largely mitigated the shortage of masks.

In their attempt to broaden the concept of development beyond economic growth, Evans and Heller (2018) argue that there can be different configurations of “embeddedness”—ties between state and non-state actors. They also point out that non-state actors can include civil society actors. To address the panic-buying of masks, the Taiwanese developmental state developed an IT system based on its national health insurance data to distribute masks swiftly. The development of such a system and apps (such as apps that show the location of pharmacies where masks are available) was based on the participation of state actors and volunteer software engineers. The collaboration of state and non-state actors has also helped to combat misinformation about the COVID-19 outbreak. Although Taiwan is a politically polarized society, the capacity of the developmental state and the embeddedness of the state in society has strengthened the trust of citizens in the government.

Taiwan’s welfare state, especially its national health insurance system, has also strengthened the country’s capacity to respond to the epidemic crisis. Similar to the situation in South Korea, the process of democratization in Taiwan imposed pressure on politicians to establish a welfare state (Peng and Wong 2008). In 1995, Taiwan replaced a previous patchwork of separate social health insurance funds with the National Health Insurance Program (NHI) (Cheng 2003). Although the NHI faces challenges in balancing the program’s budget, improving the quality of health care, and achieving higher cost-effectiveness, the program enjoys high public approval and delivers affordable and efficient health care to all Taiwanese. Different from other single-payer systems, such as those in England and Canada, the NHI does not have the problem of long waiting times for patients (Cheng 2015). Also, the NHI database serves as a valuable resource for research (Chen et al. 2011). As such, NHI provides a robust infrastructure for Taiwan to handle the COVID-19 outbreak. As mentioned, the Taiwanese state has also relied on the NHI database to build the IT system that facilitates the distribution of masks. Essentially, the national healthcare infrastructure built by the welfare state has laid a solid foundation to cope with the epidemic crisis.

Finally, the democratic political regime empowers citizens to hold the government accountable. The Taiwanese state has provided transparent and reliable statistics. Civil society in Taiwan has grown tremendously in the process of the country’s democratization. Amidst the COVID-19 outbreak, there have been public concerns and criticisms about privacy protection, protection of human rights, and how the government treats Taiwanese citizens who reside in China, naturalized citizens originating from China, international students, and undocumented migrant workers from Southeast Asia. For example, sociologists in Taiwan, the Taiwan International Workers’ Association, and various human rights organizations suggested the Taiwanese government incorporate, rather than excluding or punishing undocumented workers, so that undocumented workers would have the courage and resources to seek medical treatment. The government responded that it would not crackdown on undocumented workers.

To conclude, the democratic developmental and welfare state that emerged in Taiwan’s industrial transformation and democratization and the collective memory of SARS have helped the country to cope with the COVID-19 crisis. The Taiwanese case shows that a society does not need an authoritarian state to respond to a public health crisis. In fact, as the case of China demonstrates, the Chinese state blocked information and delayed governmental and societal responses to the COVID-19 outbreak in the beginning of the outbreak, making draconian ways of dealing with the crisis the only option. Evidence also suggests that the Chinese state has negatively influenced the operation and accountability of the WHO. The Taiwanese case further demonstrates the critical importance of building a welfare state, which takes a long time, tremendous resources, and political and societal will to accomplish. In the context of the United States, many people and media blame the current administration for mishandling the current crisis. Although such criticism is absolutely valid, the problem of the American state lies much deeper, as there is no societal consensus to improve the country’s welfare system; moreover, there is an unwarranted belief in market solutions to providing essential public goods and a long-term decline of trust in government.

References

Chen, Kow-Tong, Shiing-Jer Twu, Hsiao-Ling Chang, Yi-Chun Wu, Chu-Tzu Chen, Ting-Hsiang Lin, Sonja J. Olsen, Scott F. Dowell and Ih-Jen Su. 2005. “SARS in Taiwan: An Overview and Lessons Learned.” International Journal of Infectious Diseases 9(2):77-85.

Chen, Yu-Chun, Hsiao-Yun Yeh, Jau-Ching Wu, Ingo Haschler, Tzeng-Ji Chen and Thomas Wetter. 2011. “Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database: Administrative Health Care Database as Study Object in Bibliometrics.” Scientometrics 86(2):365-80.

Cheng, Tsung-Mei. 2003. “Taiwan’s New National Health Insurance Program: Genesis and Experience So Far.” Health Affairs 22(3):61-76.

Cheng, Tsung-Mei. 2015. “Reflections on the 20th Anniversary of Taiwan’s Single-Payer National Health Insurance System.” Health Affairs 34(3):502-10.

Evans, Peter. 1995. Embedded Autonomy: States and Industrial Transformation. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Evans, Peter and Patrick Heller. 2018. “The State and Development.” Vol. 9292565540. WIDER Working Paper.

Peng, Ito and Joseph Wong. 2008. “Institutions and Institutional Purpose: Continuity and Change in East Asian Social Policy.” Politics & Society 36(1):61-88.

Wang, C. Jason, Chun Y. Ng and Robert H. Brook. 2020. “Response to Covid-19 in Taiwan: Big Data Analytics, New Technology, and Proactive Testing.” The Journal of the American Medical Association. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3151.

Ya-Wen Lei is a Professor of Sociology at Harvard University, and is the author of The Contentious Public Sphere: Law, Media and Authoritarian Rule in China.

Comments 6

Neil Guppy

March 25, 2020Excellent contributions, all. I wonder what constitute the parallels to shequ in other jurisdictions around the world. Clearly these played an important role. I am also reminded of Gary Becker's work on addiction and people -- we are social animals and Covid-19 is challenging our social bonds.

Darryl H. Alvarez

March 27, 2020CV is one of the primary preparations when you are looking for a job. I think there are many people who work on the CV making. CV is your first impression on your boss, so try it make it a good one and now I choose https://essayguru.org/essay-editing to complete the writing task.

Ethan Taub

May 3, 2020Though the east Asian region has not been affected as much Europe and America, Still it's alarming. Needs to be very careful in future days. I have found this article very informative about the rabies vaccine for southeast Asia.

Letha Lueilwitz

May 21, 2020An aggregated media time should be established for the children. However, children must be allowed to spend this time according to their own desire. Glad to visit b spot to have fun. Parents are like a rule model to their children so they should try to set a good example.

nivedita

August 9, 2020Hello guys...your post is really very good and I appreciate it. I have found the website which is just the final answer to my search of Click here. shayari song whatsapp status

laniorlala

October 27, 2020You provided a lot of good information, it was good because it was so helpful to me. 2048