We all play a part in creating mass shooters

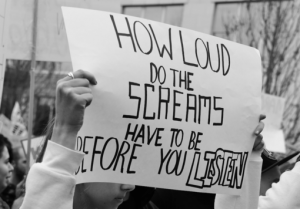

The United States does not care for people’s lives and will forget about Uvalde and Highland Park soon. At the time of writing, it has been 191 days into the year of 2022. With just 191 days, the United States recorded 384 mass shootings; we can expect two mass shootings every day. What we are saying, to us and to the rest of the world, is that life is expendable here. To explain our lack of faith in us, we have to revisit the Uvalde shooting earlier this year.

On May 24, 18-year-old Salvador Rolando Ramos shot and severely wounded his grandmother, before going to Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas where he killed nineteen students and two teachers, wounded seventeen, and left many more traumatized. Salvador did all that with a legally purchased AR-15 style rifle. Police officers waited an hour to respond despite being on-site, and it was a Border Patrol Tactical Unit who stopped this mass shooting by defying the order to wait. Politicians offered “thoughts and prayers” to the victims’ families, and Americans debated whether the U.S. has a gun/gun violence problem or if this is simply a way of politicalizing this tragedy. What’s missing, however, is the intentional learning of the killer’s life, and the multitude of systemic failures that led Salvador to that point. This, we believe, is one of the keys in stopping the creation of the next killer. And, sadly, this is also why we believe the US won’t be able to stop mass shooting and it will remain a part of our normal daily life.

An opinion piece published with HuffPost in May 27, titled Why I Don’t Care About The Uvalde Shooter’s Life And You Shouldn’t Either, is part of the reason for our pessimistic view here. The main points of that article are that 1) we shouldn’t care or learn about this killer, 2) his experiences cannot be used to explain this killing, and 3) he is a monster and there is no need for reflection on his life until he decided to kill. It is surprising to read this author believes “societal influences definitely play a part” but “don’t know what knowing that… helps us to understand.” They argue that “everyone is dejected and isolated at some point in life, but that doesn’t mean that any of us are going to commit mass murder.” And that this focus on the past is simply an effort, purposefully or inadvertently, from the media to get us sympathizing with the killer. However, they also find the 2019 op-ed that discussed four common themes of the makings of shooters, by examining mass shootings since 1966, informative. The author is rejecting the need to study killers but finding it useful to study killers. The author also infers that knowing the killer’s life and understanding what got him to this moment, would develop sympathy for the killer. We would like to respond to that article.

First, we completely agree that past struggles cannot justify killings, nor should they be used to make less of these murders or turn attention away from the victims. But we think there is much we can learn by reflecting on the shooters’ lives. Although not explained in a detailed way, the author finds the analytical work of mass shootings and shooters’ lives helpful. But they somehow reject the need to learn of Salvador’s past. An examination of Salvador’s life and decisions are a key in analyzing the structural and cultural explanations of mass shootings in the US. The identified themes from the op-ed are very useful, but we should not turn away any opportunities to reflect on the current system and culture that might nurture killers. Even if we don’t learn anything new from Salvador’s lived experience, it could reaffirm the steps we need to take. For example, Salvador was missing large portions of school and wasn’t on track to graduate. Perhaps from this we learn the need to put more emphasis on retention, children’s holistic development, and intervention at school. Hearing of Salvador’s life may be a learning moment for the government and policy makers that the current resources allocated for schools are not enough and the current system/culture might continue to play a role in developing killers.

Second, we completely agree with the author that most of us have experienced isolation and mental instabilities at various points in our lives, and not all of us fall to this level of violence. But what does it mean that we have all experienced isolation and mental instabilities? Do we all face the same experience? Do all our experiences face the same consequence? Do we have the same access to the same resources that alleviate pain and isolation? Experience is not universal and is subjected to many different variables impacting our sense of belonging, identity, and worldview. Just because we didn’t turn out one way is not good enough to expect everyone to follow. Referencing Dr. Kimberle Crenshaw’s theory of “Intersectionality,” we all have our experiences of discrimination and oppression based on different embodied identities, like race, gender, class, sexual orientation, physical ability, and more. Our experiences, including the processing of experiences, are never the same. On what ground do we expect same outcome? On a related note, if we refuse to learn from shooters’ pasts just because the rest don’t kill, we will only repeat the individualistic explanation and ignore the societal and structural explanation. We won’t know how to identify systemic failures, the role and scope of gun access, and what our society lacks.

Third, we find it difficult to understand from that article how “knowing” turns into “sympathizing”? Knowing does not lead to caring. We see no evidence suggesting we will care or sympathize with killers simply by learning of their past. The author either did not explain the logic behind this inference, or they were critiquing the media’s way of reporting. If it is the latter, we agree that media should be more intentional with their wordings, their narratives, and their framing. More can be said about this and the expansion of alternative media, but that is beyond the scope of this article.

There is much more we would like to share, including our emotions and recommendations. But this is not the place for us to share. Instead, we would like to end with an extension of what we’ve shared above: If we don’t know, we are running away from the opportunity to learn what’s wrong with our society. Which would effectively end our efforts in fixing this complex and multifaceted issue that expands beyond the scope of gun regulation, though that is a critical factor. We would be choosing reactive measures over preventative measures. If we continue to ignore these stories, we are as good as admitting that we don’t care for the lives lost in mass shootings, and we will forget Highland Park and Uvalde soon, just as we did with Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School (2018), Route 91 Harvest festival (2017), Pulse nightclub (2016), Sandy Hook Elementary School (2012), and many more. Please, US, prove us wrong.

Recommended Readings

Dimond, Diane. 2022. “OP-ED: Reducing mass shootings by recognizing red flags.” Observer-Reporter.

Ryan SC Wong is a Ph.D. student in sociology and an instructor of record at Loyola University Chicago. He is also the editorial assistant for the journal Contemporary Justice Review.

Lillian Wynne Platten is a Ph.D. student in sociology at Loyola University Chicago. Her Master’s thesis examines how active shooter drills in educational institutions impact student sense-making and socialization through peer culture and cultural reproduction. She is currently a Graduate Research Fellow at the Center for Urban Research and Learning (CURL) at Loyola University Chicago, the Qualitative Research & Evaluation Intern with the School-Based Health Alliance, and the Helen R. Weigle Fellow at Childrens Advocates for Change.

Comments