what does studying college sex tell us about immigrant assimilation?

To study immigrants’ experiences in American society, researchers often compare first- or second-generation immigrants to those whose families have been in the US for a longer time. Groups are compared on how much education they get, whether they find jobs, or how good their jobs are. In this post we explore a new approach to exploring whether or when immigrant groups assimilate to typical American cultural values—we compare immigrants and nonimmigrants on what sexual behaviors they engage in. Sexual behaviors often reflect norms, and some immigrants come from cultures with substantially different norms about sexuality than those typical in the US. Thus, immigrants may retain some influence from their sending culture, either because they spent some of their youth there, because their parents retain these values, or because they are immersed in an immigrant community promoting these norms. At the same time, immigrants will be affected by their American peers. Therefore, we might expect immigrants to be distinctive in their sexual behaviors, and expect these differences to erode across generations.

Here we compare college students whose families have been in the US for a different number of generations in terms of whether or how much they have hooked up or had sex in college. We want to know if immigrants participate less in the college “hookup culture,” perhaps because they come from countries where sex among single, young adults is less accepted.

We used data from the Online College Social Life Survey (OCSLS), a survey of more than 20,000 students from 21 four-year colleges and universities in the US, collected between 2005 and 2011.

We divided students into three categories of immigrant status:

- First-generation immigrants are students who are not born in the US.

- Second-generation immigrants are students who have either a mother or father, or both, who are not born in the US. (Of course, although these individuals are called “second-generation immigrants,” strictly speaking, they are not immigrants but they had a parent who was.)

- “Non-immigrants” are students born in the US, whose parents are also born in the US; their families have been in this country for at least three generations.

The graphs we show below compare these three groups, giving an average or percent for each behavior. These averages or percents are regression-adjusted, as explained in the technical appendix. This procedure adjusts out of any of the differences the portion caused by the groups being different on two background variables: mother’s education, as a approximate measure of social class background, and age. For example, if some behavior is less common among first-generation immigrants, and this behavior is also less common among those whose mother had less education, we want to isolate that part of the lower incidence of the behavior among first-generation immigrants that is due, not to their mothers’ education, but to some other aspect of being a first-generation immigrant. The regression-adjusted differences between first-generation immigrants and second-generation immigrants or non-immigrants show us this.

We provide comparisons across the three immigrant-status groups separately for men and women, and within each sex, separately within each of the four racial-ethnic groups: Blacks, East Asians, Latina/os, and Whites. For more details on what we did, and tables with complete results, see the Technical Appendix at the end of this post.

Patterns for Women

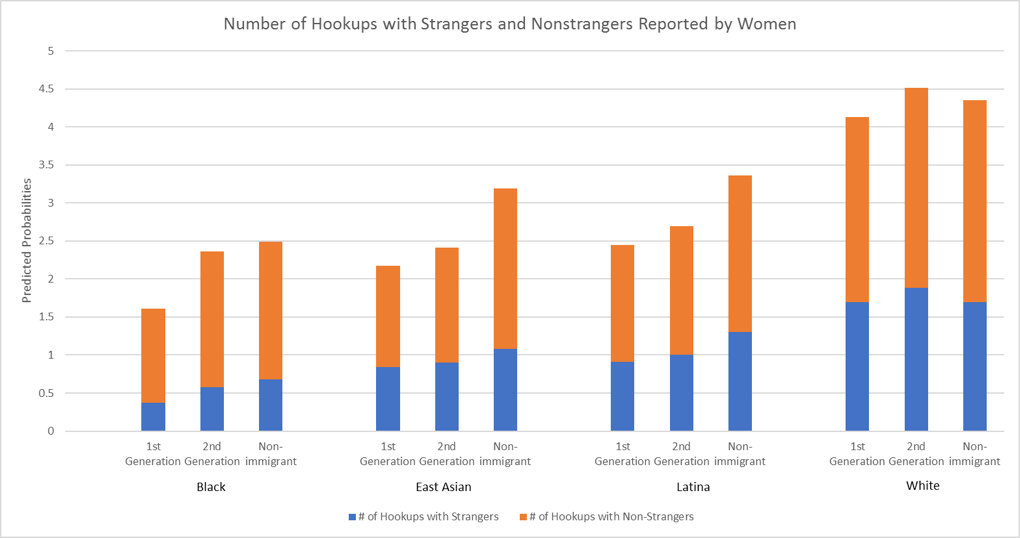

Since a “hookup culture” is present on many campuses, we ask whether immigrants hook up less than other students. A “hookup,” as students use the term, means that two people who are not already in an exclusive relationship got together without a pre-arranged “date,” and something sexual happened. The sexual behavior is sometimes, but not always, intercourse. (About 40% of hookups involve intercourse.) The survey asked students about what they have done since they started college—for the number of hookups they have had with strangers, and with people they knew, but whom they were not already in a relationship. To interpret these numbers, it helps to know how long the average student in the sample had been in college. They ranged from less than a year to more than 6 years, but the average amount of time they had been in college was a approximately 2 years.

The graph below shows that for Black, East Asian, and Latina women, hookups are more common among non-immigrants than immigrants, and more common among second than first-generation immigrants. In contrast, among White women, there is not a stair-step pattern where more generations in the country equate to more hookups. This suggests that the societies White immigrants come from, such as Canada or Europe, do not differ so much from the US in their “hookup culture.”

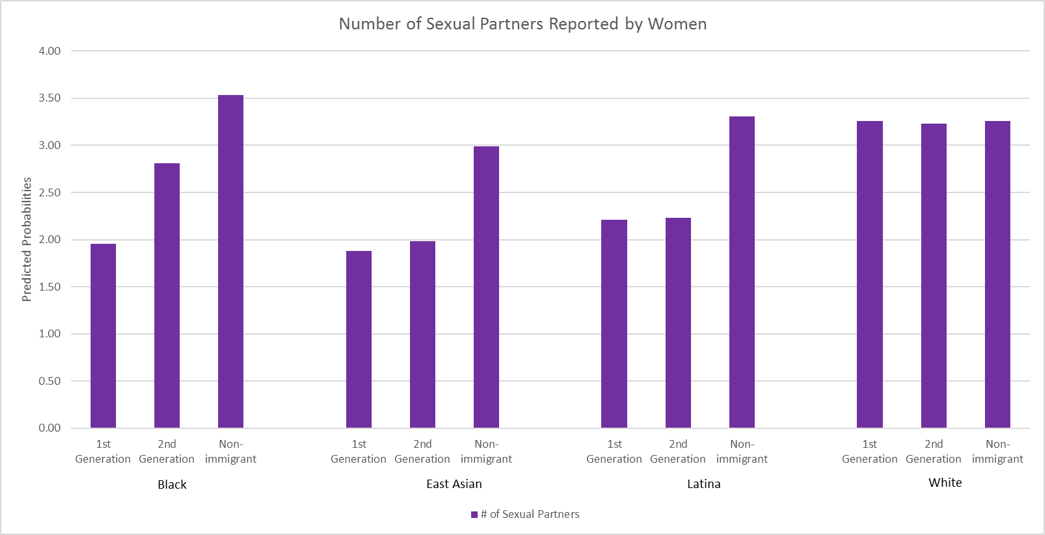

Hookups often involve intercourse, but not always, and, of course, some sex may happen on dates or in relationships rather than in hookups. Thus, to see if immigrants are generally more conservative regarding sex, we looked at their number of sexual partners in the graph below. For Blacks, East Asians, and Latinas, this pattern holds across the board except that first- and second-generations are not very different among Latinas. Again, we see that among Whites, immigrants are not distinctive.

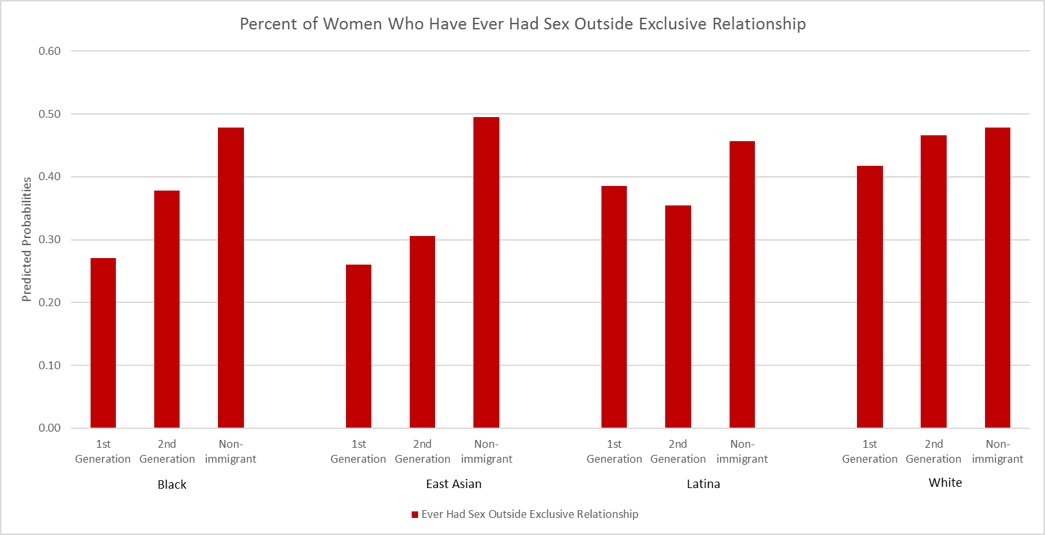

Hookups do not always involve intercourse, but when they do, it is sex outside a relationship. One question on the survey, which tapped into this, asked students whether they have had sex outside of an exclusive relationship. The next graph shows that among Blacks, East Asians, and in this case Whites, first-generation immigrants are the least likely, second-generation more likely, and nonimmigrants the most likely to have had sex outside an exclusive relationship. Latinas do not quite fit the pattern, in that second-generation women are slightly less likely than first generation to have had sex outside an exclusive relationship, but they do fit the pattern in that non-immigrants are more likely to have done this than either first- or second-generation immigrants.

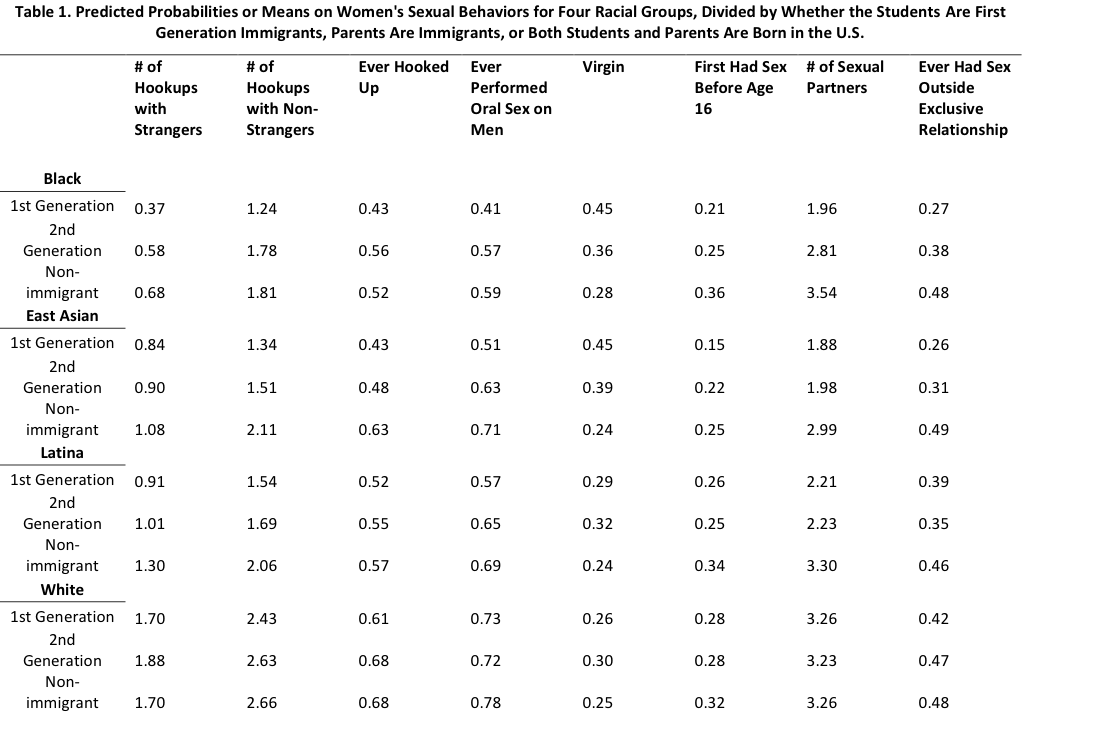

This pattern holds for other sexual behaviors as well, at least for some groups, as is shown in Table 1 at the end of this post. For example, regarding whether women have ever given a man oral sex, 41% of first-generation Black immigrants have done so, compared to 57% of second-generation immigrants, and 59% of he percent of students who were still virgins at the time of the survey shows a steady decline across generations, but only for Blacks and East Asians. (All numbers in this paragraph are from Table 1 below.)

Thus, for all the behaviors considered, among Black and East Asian women, first-generation immigrants engage least in hooking up and sex during or before college, with nonimmigrants the most likely to participate. Latinas show this pattern for some behaviors as well. White women’s sexual behavior does not vary by immigrant status for most of the behaviors.

Patterns for Men

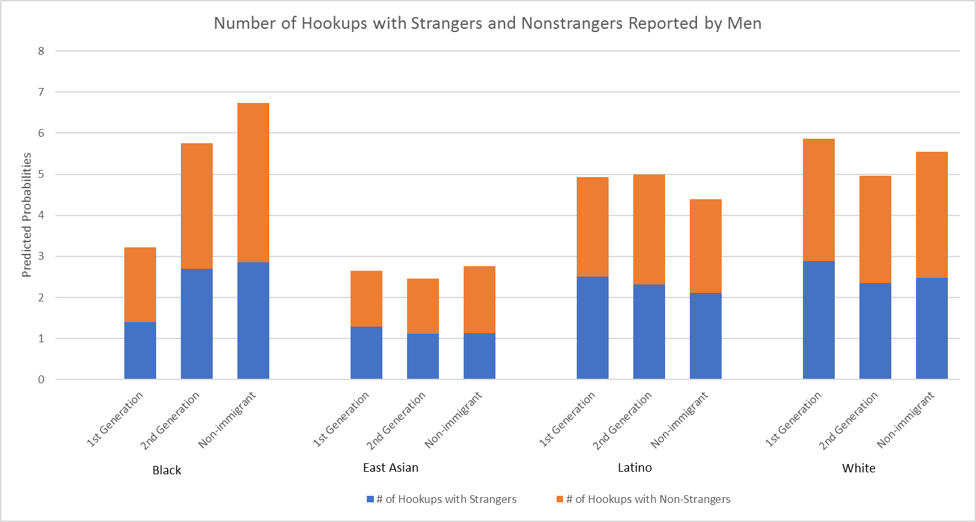

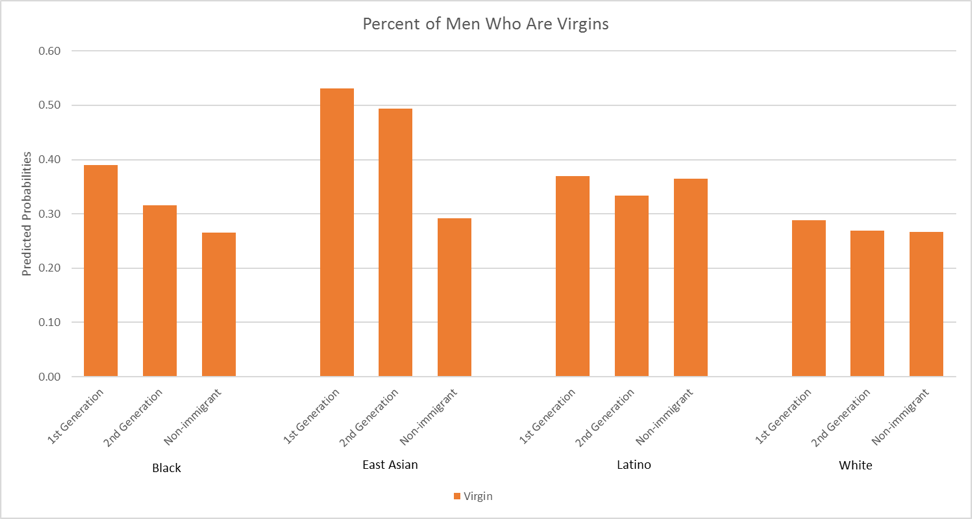

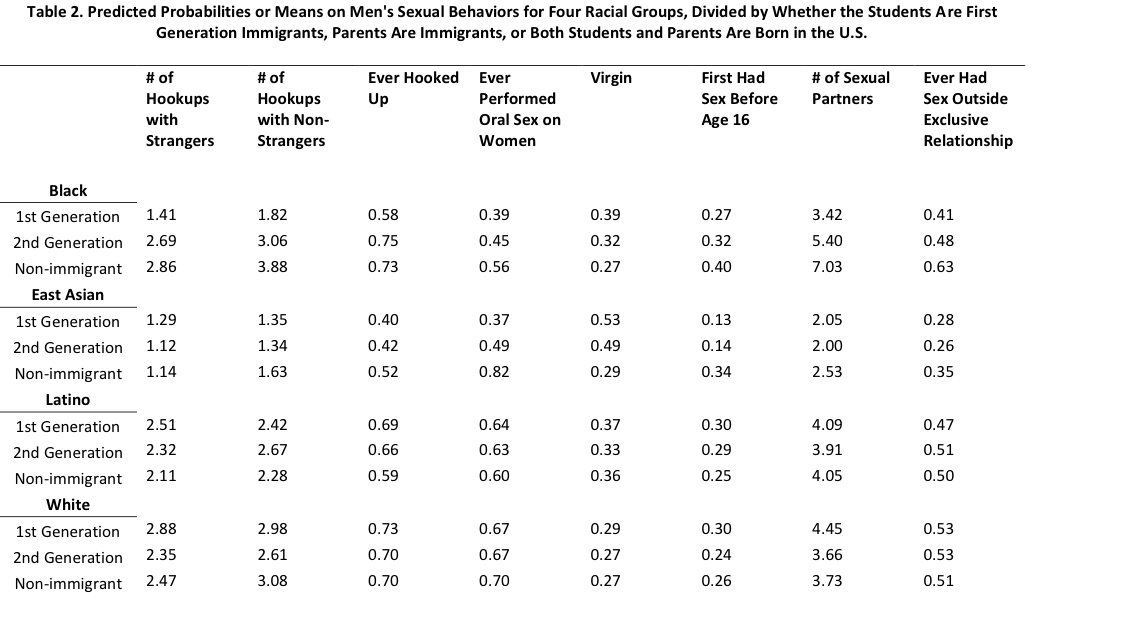

Contrary to our findings for women, men’s probabilities of hooking up are not as closely related to immigrant status as are women’s. The exception is Black men for whom this pattern does hold, almost across the board. As Table 2 at the bottom of the post shows, Blacks show the stair-step pattern of progressively more permissiveness across generations for all behaviors except one (whether they ever hooked up, but the pattern does hold for number of hookups). Non-immigrant Black men are most likely, and first-generation immigrants least likely to be a nonvirgin, have had first sex before age 16, have performed oral sex on a woman, had more sexual partners, and had sex outside an exclusive relationship. No such pattern exists for Whites or Latinos. For East Asians, the pattern is present for three of the behaviors—whether the young man has ever hooked up (40% of first-, 42% of second-generation immigrants, and 52% of nonimmigrants), whether he has ever given oral sex to a woman, and whether he is a virgin.

This graph shows men’s number of hookups; among Black men hooking up is more common among second- than first-generation immigrants, and most common among non-immigrants. But this pattern does not hold for other racial-ethnic groups of men who hook up just as much or more in the first generation as the third and beyond.

When we look at the results for the simple question of whether the man is a virgin at the time of the survey, we see effects of immigrant status for both Black and East Asian men, but no clear pattern for Latinos or White men.

Overall, immigrant status makes much less difference for college men than college women. The exception to this is Black men, for whom immigrants are distinctive on most sexual behaviors.

Conclusion and Interpretive Speculations

We have shown a pattern among some racial-ethnic groups in which individual sexual behaviors show the most permissiveness among those whose families have been in the country three or more generations, and the most restraint among first-generation immigrants, with the children of immigrants, the second generation, in between. Where we found this pattern, what does this tell us about immigrant assimilation? It suggests that successive generations assimilate more to the culture of the country they are in—in this case a college culture involving hooking up and sex. To put it another way, we think this is evidence that first-generation immigrants are affected by both societies they have lived in. Even second-generation immigrants appear to be affected by the societies their parents came from, presumably through being socialized by their parents and sometimes through immersion in an immigrant community.

But, this pattern of immigrant-status effects differs by gender and race, providing an example of intersectionality. First, White immigrants seldom differ from Whites whose families have been here generations. Perhaps this is because the cultures—as least as regards sexual behavior—from which White immigrants come (for example, Canada and Europe), are not very different than American culture. Second, among Latinos we see the pattern wherein immigrants are more conservative on some behaviors, but less so than for Blacks and East Asians who exhibit the pattern most clearly. Black immigrants are generally from Africa or the Caribbean, while the families of most East Asians in the sample are from China, Taiwan, or Vietnam.

Gender also intersects with immigrant status. Among women, many behaviors differ by immigrant status, and this is overwhelmingly true for Blacks and East Asians, and often true for Latinos. It is a general pattern for every group of women except Whites. What does this mean? Virtually every culture restricts women’s sexual behavior more than men’s—this is part of what we mean when we refer to the sexual double standard. This is true for US culture as well. But among some groups—particularly East Asians and Latinos—immigrant status has strong effects for women but very little or much less effect for men. This suggests the hypothesis that the cultures from which these racial-ethnic groups of immigrants hail have standards of conduct more differentiated by gender than is true for Whites or Blacks. For both Whites and Blacks the patterns are more similar across gender, with both men and women showing few differences by immigrant status for Whites, and both men and women showing a strong gradient of less permissiveness for immigrants among Blacks.

Technical Appendix: Information on the OCSLS and Our Statistical Procedures

We used the OCSLS (Online College Social Life Survey) data. The OCSLS surveyed over 20,000 students from 21 U.S. four-year colleges and universities between 2005 and 2011. The survey asked questions about students’ experiences with dating, hooking up, relationships, and sexuality. The OCSLS was not a panel study; we did not follow participants over time. In order to minimize atypical experiences, we exclude students who are over 24 years of age.

The colleges and universities in the OCSLS include private colleges and universities as well as state universities. The majority of the students who participated in the survey attended state universities; many of them were the flagship university of a state. While the original dataset contained one Community College, we dropped these students, so that our analysis pertains to those in four-year institutions. The percentage of sample in various years in school was 35% freshmen, 23% sophomores, 20% juniors, and 17% in their fourth or higher year.

A limitation of the OCSLS is that neither the sample of schools nor the sample of students within each school is a probability sample. Most of the data was obtained through agreements with professors to offer points of extra credit to students who took the online survey; thus, in most classes, nearly 100 percent of students participated. Therefore, any non-representativeness of the sample is a result of which schools we chose and which students enrolled in the classes that recruited participants. Although most of the classes sampled were sociology courses, many students take sociology courses as electives; thus only approximately 10% of the participants were sociology majors.

The OCSLS asked students taking the survey three questions about their immigrant status. The questions read:

- Were you born in the United States (one of the 50 states or Washington DC)?

- Was your mother born in the United States (one of the 50 states or Washington DC)?

- Was your father born in the United States (one of the 50 states or Washington DC)?

Students were considered a first-generation immigrant if they were not born in the US. They were considered a second-generation immigrant if either their mother or father, or both parents, were not born in the US. (Of course, strictly speaking these people are not immigrants; their parents are.) We use the term “non-immigrants” for students who were born in the US, and whose parents were both born in the US; their families have been in this country at least three generations.

Utilizing the OCSLS data set, we ran regressions predicting students’ various sexual behaviors separately for men and women of four racial-ethnic groups: Blacks, East Asians, Latino/as, and Whites. Two other racial-ethnic groups were in the data, South Asians and a residual Other category, but they were too small for separate analysis so were omitted. For count variables (i.e. number of sexual partners, number of hookups with strangers and nonstrangers), we used negative binomial regressions. For dichotomous variables (e.g. are you a virgin) we used logistic regressions.

We divided our comparisons by race, because, as we will show, among Whites, immigrants are not very different from non-immigrants, perhaps because most White immigrants hail from European and Canada, whose cultures regarding sex are not more conservative than that in the U.S. Thus, we show results separately for Whites, Blacks, East Asians, and Latinos.

For each dependent variable (sexual behavior), we estimated separate regressions for each of the four racial-ethnic groups of men, and each of the four racial-ethnic groups of women. Indicator variables for the immigrant status categories (first generation, second generation, and nonimmigrant) were our predictors of major interest in the regressions. Indicator variables representing two factors were entered as controls: age (each year from 18 to 24) and mother’s level of education (high school or less; some college; BA or more).

The sexual behaviors our models predicted include whether students have ever hooked up, and how many hookups they had experienced with strangers as well as nonstrangers. The survey also asked if they ever performed oral sex on the other sex. Due to the polysemy of the “hookup,” we also analyzed responses related to sexual debut; if students were virgins at survey, and whether they had had sex before 16 years of age. We also examine how many sexual partners they had had, and whether they had ever had sex outside an exclusive relationship.

From our regression coefficients, we calculated predicted probabilities (percents) or predicted means for every behavior for each of the three categories of immigrant status (using margins in Stata). Our graphs and the tables below contain these predicted means or percents by immigrant status. The reason we prefer regression-predicted (i.e. regression-adjusted) means and percents to simple descriptive means and percents is that the former adjust out any part of the immigrant group differences that are explained by immigrant group differences in social class background, as measured by their mother’s education, and their age.

Table 1 gives all our results—the adjusted means or percents—for women and Table 2 gives results for men. Each of the two tables divides students by race-ethnic group. We show results for Blacks, East Asians, Latino/as, and Whites. The comparisons the tables highlight are those between first-generation immigrants, second-generation immigrants, and non-immigrants.

A caveat: Because we did separate regressions by sex-and-race-ethnic-specific groups, neither gender differences nor race-ethnic differences are adjusted for differences in class background and age. It is the immigrant group differences within gender and racial-ethnic groups that have this adjustment in force.

When we ran models that pooled all races together, we found few immigrant-status effects. This is because there are few immigrant-status effects for Whites, but Whites numerically dominate the sample. It was only when we did separate analyses by race-ethnicity and by gender that we realized that there are more consistent patterns for women than men, and for Blacks and East Asians than Latinos.

Researchers who wish to use the OCSLS data can contact Paula England at pengland@nyu.edu for information on how to download the data.

Kristine Wang is an undergraduate Sociology major at NYU. Jessie Ford is a doctoral student at NYU Sociology, where Paula England is Silver Professor.

Comments 4

Brandon Palmer

May 23, 2019In many ways, education plays a very large role in our life and today we often do not find a place for help. It is always difficult to do everything yourself so that it is easier to learn you always need to use where you can view source pay for research paper in Canada. So for me, this is an ideal opportunity to improve your knowledge.

Anna

March 23, 2020Nice!

Bgrea

June 23, 2020Thank you for sharing. I often read educational portals becouse I want to learn more or improve some of my skills. This year I graduated from high school and now I need to prepare for admission. I want to try applying at Florida State University. I know that it’s not easy to enter this university, so now I’m looking for a way to increase my chances. I would like you to share your experience in writing an admission essay, maybe you could give me some tips on how I can write a more impressive essay. This article https://admission-writer.com/blog/writing-fsu-essay has a lot of good recommendations and cool ideas on how I can improve my essay, maybe it will be interesting for you too. It seems to me that choosing the right strategy for writing an essay at such a prestigious university is very difficult, because you are trying to write about what sets you apart from other candidates, but you can never be sure that this is exactly what the selection committee members are looking for in their students.

greyasanna

October 26, 2020CBDistillery is the online association established in 2016 in Colorado. At this stage of life, CBDistillery is the internationally recognized brand in the CBD hemp market. The current online store manufactures a reasonable number of products, including therapeutic CBD oils. These products are cbdistillery review produced in the United States and, furthermore, abroad. CBDistillery is mainly known for its affordable prices, as well as a great online collection that involves CBD oils, fumes, foods, topicals, etc.